Carshalton College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance Fields Conference Boa NEW

Dance Fields Conference April 19th – 22nd 2017 Book of Abstracts (Chronologically listed) SESSIONSPANELSPRACTICALSWORKSHOPSROUND TABLES Thursday, April 20th 10:00 – 11:30 Session I Chair: Ann R. David Michael Huxley Dance Studies in the UK 1974-1984: A historical consideration of the boundaries of research and the dancer’s voice The first Study of Dance Conference was held at the University of Leeds in 1981. The following year saw the First Conference of British Dance Scholars in London, leading to the inauguration of the Society for Dance Research and then the publication of its journal, Dance Research. Since 1984, the field of dance studies in the UK has both developed and been debated. My paper draws on archival and other sources to reconsider this period historically. With the benefit of current ideas of what constitutes dance, practice, research, and history, it is possible to consider the early years of UK Dance Studies afresh. In the twenty-first-century there are some accepted notions of dance studies. I would argue that they have established boundaries, but that these are often unstated. The period is re-examined with a view to uncovering a broader, and indeed more inclusive, idea of dance studies. In this, attention is given to the researches of practitioners in the period; both published, including in New Dance, and unpublished. Whilst recognising the significant scholarship of the period, the paper also considers the ideas that dancers gave voice to. The analysis is taken further by considering the unexamined discourses that helped enable research in dance in the UK to develop in the way it did. -

Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies

Sharing of Personal Information Contents Qualifications – Awarding Bodies ........................................................................................................... 2 UK - Universities ...................................................................................................................................... 2 UK - Colleges ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Glasgow - Schools ................................................................................................................................. 12 Local Authorities ................................................................................................................................... 13 Sector Skills Agencies ............................................................................................................................ 14 Sharing of Personal Information Qualifications – Awarding Bodies Quality Enhancement Scottish Qualifications Authority Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) City and Guilds General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) General Certificate of Education (GCE) Edexcel Pearson Business Development Royal Environmental Health Institute for Scotland (REHIS) Association of First Aiders Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM) Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) UK - Universities Northern Ireland Queen's – Belfast Ulster Wales Aberystwyth Bangor Cardiff Cardiff Metropolitan South Wales -

Part 2 – Confidential Facts and Advice

Appendix A – Project List Successful Projects GLA capital Proj ect ti tl e Organisation contribution IT enabled S E ND provision New City College £300,000.00 Developing Invitational Centres London Borough of Lewisham Regeneration Unit £300,000.00 Outstanding Digital E xperience for Learners The City Literary Institute £219,714.00 Expanding Adult Education Digitally in Communities RB K ingston Upon Thames (K ingston Adult E ducation) £94,000.00 Digital Inclusion at WAES City of Westminster Council (WAES) £75,500.00 E xpansion of The Right Course LTE Group - Novus £108,376.00 Inspiring spaces: lecture and screening auditorium The City Literary Institute £231,516.00 Upgrading SEND facilities Barking & Dagenham College £300,000.00 Improving Learner E ngagement S utton College £69,450.00 Digital media for construction proposal Waltham Forest College (RH Architects) £300,000.00 Investing in Sculpture Skills Morley College London £80,500.00 MITSkills Limited Brentford Capital Bid 2019 MITSkills Limited £35,000.00 Building Infrastructure S kills for the F uture LONDON SKILLS & DEVELOP MENT NETWORK £65,000.00 British Academy of J ewellery British Academy of J ewellery £42,862.00 Design Innovation Room LB Redbridge - Redbridge Institute Community Learning and S kills £25,000.00 S ports facilities for sixth form students St Charles Sixth Form College £48,000.00 P erforming Arts S pace and S E ND Training K itchen S outh Thames Colleges Group £222,500.00 Outreach IT E ast London Advanced Technology Training (E LATT) £53,702.00 Improving Learning through -

Enrolment Guide (PDF, 540.36KB)

ENROLMENT INFORMATION FOR LOCAL/ CENTRAL LONDON COLLEGES Please see the Guide to Results Day 2018 for further and information and advice on what to do once you receive you’re A Level or GCSE results. The listings below provide you with enrolment information for local and central London Colleges. For sixth forms please refer to the Croydon Post 16 Prospectus or https://www.croydon.gov.uk/education/adult/16-19-education-training- careers for details and contact them directly as soon as possible. TITLE & DATE/TIME ENROLMENT INFORMATION CONTACT DETAILS Dates/Times: Croydon College Web: Tuesday 28th August / 9:00am-7:00pm You will need your passport or a British https://www.croydon.ac.uk/ Wednesyday 29th August / 9:00am-7:00pm birth certificate. If your passport is not Thursday 30th August / 9:00am-7:00pm British or from a country in the European Tel: Friday 31st August / 9:00-4:00pm Union / Iceland / Liechtenstein / 020 8760 5934 Monday 3rd September / 9:00am-5:00pm Switzerland / Norway then we will need to Tuesday 4th September / 9:00am-5:00pm see your and/or Home Office Email: Wednesday 5th September/ 9:00am-7:00pm documentation. [email protected] Thursday 6th September / 9:00am-5:00pm Friday 7th September / 9:00am-4:00pm GCSE certificates / results slips MUST BOOK A PLACE ONLINE Dates: Capel Manor Web: Wednesday 22nd August / Wednesday 29th August http://www.capel.ac.uk/ Time: Please research which documents are 11:00am – 7:00pm applicable for your enrolment and ensure Tel: you bring them with you. 0303 003 1234 Email: [email protected] 1 Dates: Carshalton College Web: https://carshalton.ac.uk/about/enrolment Wednesday 22nd August / 9:00am-5:00pm Please research which documents are Thurday 23rd August / 9:00am-8:00pm applicable for your enrolment and ensure Tel: Friday 24th August 9:00am-4pm you bring them with you. -

Education, Employment and Training (Eets) Guide

CS.1921 (3.21).qxp_Layout 1 30/03/2021 15:30 Page 1 WANDSWORTH VIRTUAL SCHOOL Education, employment and training guide for care experienced young people CS.1921 (3.21).qxp_Layout 1 30/03/2021 15:30 Page 2 CONTENTS Virtual School 4 Colleges and 6th forms 5 Thinking about university? 10 Apprenticeships, internships, training and employment 20 Volunteering 31 Part-time work 32 Money matters 33 Self-employment opportunities 37 Your voice matters 39 Leisure centres and libraries 42 Information and advice 43 My education journey has made me forget about my past problems and has motivated me to focus on my future aspirations. Bethany, 20, studying International Social and Public Policy at London School of Economics CS.1921 (3.21).qxp_Layout 1 30/03/2021 15:30 Page 3 WELCOME FROM VIRTUAL SCHOOL HEADTEACHER A wise person once said to me... ‘...reach for the moon and then keep reaching further’ What this meant to me was to never limit your horizons, take every opportunity that comes your way. Education, knowledge and skills are your toolkit for life – they are something you achieve and take with you as you journey towards your future goals. Once you have them, they’re yours and yours only. This guide is intended to equip you with questions you want advice about when talking to your social worker, PA or Virtual School advisor – it is important to remember that as corporate parents, we are here to guide and support you along your journey. I hope you will find some inspiration in this guide to help you navigate towards your aspirations and dreams. -

Institutions Teaching Japanese in the UK

Institutions Teaching Japanese in the UK This list features institutions in the UK that teach Japanese outside of the primary and secondary sector (e.g., language schools, evening classes, adult education, in-house training, public lectures etc.). There is also a list on the back page of nursery schools and Saturday schools that cater to mother-tongue level Japanese-speaking children. Please note: The Japan Foundation has no proprietary interest in any of the organisations mentioned and inclusion on the list does not constitute a recommendation, nor does the list claim to be exhaustive. For a list of primary and secondary schools teaching Japanese, please see our online List of Schools Teaching Japanese at www.jpf.org.uk/language. * = Universities offering Japanese as a degree course Japan Foundation London Russell Square House, 10-12 Russell Square, London WC1B 5EH Tel: 020 7436 6698 Fax: 020 7323 4888 email: [email protected] Website: www.jpf.org.uk Twitter: @jpflondon ENGLAND - London Name of Institution Website Local authority The Learning Centre Bexley www.thelearningcentrebexley.ac.uk Bexley City Lit www.citylit.ac.uk Camden Birkbeck, University of London* www.bbk.ac.uk Camden Japan Foundation London www.jpf.org.uk Camden SOAS University of London* www.soas.ac.uk Camden University College London www.ucl.ac.uk Camden Westminster Kingsway College www.westking.ac.uk Camden The Working Men's College www.wmcollege.ac.uk Camden Bishopsgate Institute www.bishopsgate.org.uk City of London City University www.city.ac.uk City of London -

FREE Course at the Japan Foundation London

Institutions Teaching Japanese in the UK and Ireland This list features institutions in the UK that teach Japanese outside of the primary and secondary sector (e.g. colleges, language schools, evening classes, adult education, in-house training, public lectures etc.). There is also a list on the back page of nursery schools and Saturday schools that cater to mother-tongue level Japanese-speaking children, as well as online Japanese language courses. Please note: The Japan Foundation has no proprietary interest in any of the organisations mentioned and inclusion on the list does not constitute a recommendation, nor does the list claim to be exhaustive. For a list of primary and secondary schools teaching Japanese, please see our online List of Schools Teaching Japanese at www.jpf.org.uk/language. To suggest additions and updates to this list, please email Japan Foundation at [email protected]. * = Universities offering Japanese as a degree course Japan Foundation London Lion Court, 25 Procter Street, London. WC1V 6NY Tel: 020 3102 5021 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jpf.org.uk Last updated: 18/01/2016 ENGLAND - London Name of Institution Website Local authority The Learning Centre Bexley www.thelearningcentrebexley.ac.uk Bexley Alpha Japanese School www.alphalondon.co.uk Camden City Lit www.citylit.ac.uk Camden *Birkbeck, University of London www.bbk.ac.uk Camden Japan Foundation London www.jpf.org.uk Camden Sakura-kai [email protected] Camden *SOAS University of London www.soas.ac.uk Camden University -

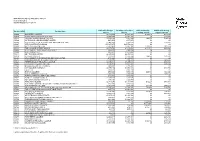

Allocations Data 201213

Skills Funding Agency Allocations 2012/13 as at 20 April 2012 SkillsFundingAgency-P-120115 Adult Skills Budget 16-18 Apprenticeships Adult Community Additional Learning Provider UPIN Provider Name 2012/13 2012/13 Learning 2012/13 Support 2012/13 105000 BARNFIELD COLLEGE £6,114,422 £1,488,649 £199,572 £872,604 105010 NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE COLLEGE £9,557,877 £3,564,335 £0 £479,854 105017 CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE £3,269,194 £357,364 £40,158 £284,133 105044 UK TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT LIMITED £459,559 £857,450 £0 £0 105493 OTLEY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND HORTICULTURE £2,091,092 £378,660 £0 £79,291 105927 CITB-CONSTRUCTIONSKILLS £15,277,477 £25,750,396 £0 £0 105936 WEST SUFFOLK COLLEGE £5,024,972 £2,081,108 £120,476 £302,419 105939 THE COLLEGE OF WEST ANGLIA £5,972,746 £1,832,412 £131,519 £242,424 105969 STARTING OFF (NORTHAMPTON) LIMITED £263,373 £395,530 £0 £0 106089 W S TRAINING LTD. £827,912 £1,122,407 £0 £0 106311 KEY TRAINING LIMITED £2,358,980 £2,972,036 £0 £0 106319 BEDFORD COLLEGE £7,213,588 £1,975,456 £90,357 £438,703 106325 MANAGEMENT AND PERSONNEL SERVICES LIMITED £738,244 £1,345,079 £0 £0 106402 HUNTINGDONSHIRE REGIONAL COLLEGE £4,296,005 £468,495 £0 £609,561 106409 PETERBOROUGH REGIONAL COLLEGE £4,154,833 £1,465,066 £0 £183,341 106658 HERTFORD REGIONAL COLLEGE £4,208,710 £1,544,091 £0 £456,460 106945 BROADLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL £203,989 £731,481 £0 £0 106947 CITY COLLEGE, NORWICH £4,750,102 £1,553,883 £0 £313,796 106948 EAGIT LTD £103,149 £882,119 £0 £0 106949 EASTON COLLEGE £959,280 £572,170 £40,158 £82,622 106950 GREAT YARMOUTH -

Barnet College

Where to Pot in London Guide May 2020 Disclaimer Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this guide. For full course details, please contact the colleges, co-operatives or individual potters direct. London Potters accepts no responsibility for courses that are altered or cancelled. Inclusion in this guide does not imply a recommendation for the courses offered. If you would like a free entry in future editions, please contact London Potters E: [email protected] www.londonpotters.com Reg Charity No 1086355 Aspire@Southfields Hammersmith & Fulham Adult Learning 337 Merton Road, London SW18 5JU and Skills Service T: 020 8875 2603 Macbeth Centre, Macbeth Street, London W6 9JJ www.aspiresouthfields.com and Hurlingham Academy, Peterborough Road, London SW6 3ED Learning & Enterprise College Bexley T: 020 7753 3600 5 Brampton Road, Bexleyheath, Kent DA7 4EZ E: [email protected] T: 020 3045 5176 www.hfals.co.uk E: [email protected] www.lecb.ac.uk Hampstead School of Art Penrose Gardens, Hampstead, London NW3 7BF Brent Start T: 020 7794 1439 New Millennium Centre, 1 Robson Avenue, London E: [email protected] NW10 3SG www.hampstead-school-of-art.org T: 020 8937 3950 E: [email protected] Harrow College www.brent.gov.uk/brentstart Harrow Weald Campus, Brookshill, Harrow Weald, Middx HA3 6RR Brunel University T: 020 8909 6000 The Arts Centre, Kingston Lane, Uxbridge E: [email protected] UB8 3PH www.harrow.ac.uk T: 01895 266074 E: [email protected] Heatherley School of Fine Art www.brunel.ac.uk/brunelarts -

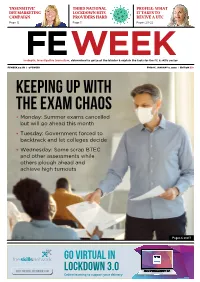

Keeping up with the Exam Chaos

'INSENSITIVE' THIRD NATIONAL PROFILE: WHAT DFE MARKETING LOCKDOWN HITS IT TAKES TO CAMPAIGN PROVIDERS HARD REVIVE A UTC Page 12 Page 5 Pages 20-22 In-depth, investigative journalism, determined to get past the bluster & explain the facts for the FE & skills sector FEWEEK.CO.UK | @FEWEEK FRIDAY, JANUARY 8, 2020 | EDITION 338 keeping up with the exam chaos Monday: Summer exams cancelled but will go ahead this month Tuesday: Government forced to backtrack and let colleges decide Wednesday: Some scrap BTEC and other assessments while others plough ahead and achieve high turnouts Pages 6 and 7 Go virtual in Visit theskillsnetwork.com lockdown 3.0 Online learning to support your delivery @FEWEEK EDITION 338 | FRIDAY, JANUARY 8, 2020 MEET THE TEAM Nick Linford Shane Mann Billy Camden EDITOR MANAGING DEPUTY DIRECTOR EDITOR @NICKLINFORD @SHANERMANN @BILLYCAMDEN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] JL Dutaut Jess Staufenberg Fraser COMMISSIONING COMMISSIONING Whieldon EDITOR EDITOR REPORTER @DUTAUT @STAUFENBERGJ @FRASERWHIELDON [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] THE TEAM Simon Kay DESIGNER HEAD DESIGNER Nicky Phillips ? [email protected] DESIGNER Simon Kay SALES MANAGER Bridget Stockdale ADMINISTRATION Frances Ogefere Dell EA TO MANAGING Get in touch. DIRECTOR AND FINANCIALS Victoria Boyle Contact [email protected] or call 020 81234 778 REDBRIDGE INSTITUTE PRINCIPAL £56,154 - £66,579 PER ANNUM FEATURED https://httpslink.com/e67o JOBS WESTON COLLEGE APPRENTICESHIP QUALITY MANAGER £37,000 - £38,000 PER ANNUM https://httpslink.com/lg83 BPP PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION QUALITY IMPROVEMENT MANAGER £40,000 - 45,000 PER ANNUM THIS WEEK’S TOP AVAILABLE JOBS IN THE FE SECTOR. -

Learning and Skills for Neighbourhood Renewal: Final Report to the Neighbourhood Renewal Unit

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 592 CE 085 617 AUTHOR Taylor, Sue; Doyle, Lisa TITLE Learning and Skills for Neighbourhood Renewal: Final Report to the Neighbourhood Renewal Unit. Research Report. INSTITUTION Learning and Skills Development Agency, London (England). ISBN ISBN-1-85338-909-9 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 77p.; Supported by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Neighbourhood Renewal Unit. For a summary of this report, see CE 085 397. AVAILABLE FROM Learning and Skills Development Agency, Regent Arcade House, 19-25 Argyll Street, London W1F 7LS, United Kingdom (Ref. No. 1521) .Tel: 020 7297 9000; Fax: 020 7297 9001; Web site: http://www.lsda.org.uk/home.asp. For full text: http://www.lsda.org.uk/fi1es/pdf/1521.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Adult Learning; Benchmarking; Community Development; *Community Education; *Economic Development; Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; *Neighborhood Improvement; *Partnerships in Education; Policy Analysis; Postsecondary Education; *Poverty Areas; Public Policy; *School Community Relationship; Skill Development; Social Change; Social Services; Strategic Planning; Urban Areas IDENTIFIERS Best Practices; *United Kingdom ABSTRACT A study of adult learning and neighborhood renewal examined how further education (FE) colleges and Local Education Authority (LEA) adult education services contribute to neighborhood renewal in deprived areas and considered how their strategic role might develop in this field. The study indicates that the policy framework for post-16 learning and skills introduced in 2001 has the potential to be very helpful to the development of learning and skills for neighborhood renewal. However, because it is but one of many issues within the Learning and Skill Council's (LSC) span of control, key stakeholders in the sector may not yet be fully aware of its importance and their potential role in delivering it. -

Environment Template (REF5) Institution: Middlesex University

Environment template (REF5) Institution: Middlesex University (UKPRN: 10004351) Unit of Assessment: 36 – Communication, Cultural and Media Studies, Library and Information Management a. Overview Research in this Unit is largely focused around three broad and overlapping strengths: media industries; cultural studies; language and writing. These groupings are flexible and dynamic, encouraging the emergence of new individual and collaborative activity and interests. A commitment to socially engaged research and the enhancement of professional practices in the creative, cultural and education sectors guides research in this Unit, which is conducted through the development of interdisciplinary, practice-led and problem-based forms of enquiry. This submission (of 22 staff members, or 19.6 FTE) consists of work carried out principally by researchers in the recently formed School of Media and Performing Arts (2012), under the leadership of Upton (Dean and Professor). The School houses two departments: this Unit correlates closely with the Department of Media. The formation of the School was part of a major University restructure, directing the strategic future of the institution toward high-quality research within an international context. The research profile of the Unit is matched by an established reputation for teaching and its diverse portfolio of degree programmes in Media at undergraduate and postgraduate levels and includes a successful and growing doctoral student community. b. Research Strategy The research strategy for this Unit is framed by an ambitious institutional vision. This submission plots an energetic and purposeful trajectory since the 2008 RAE return to UoA66, building and diversifying from our historical strengths in cultural theory. From a modest base in 2008 we have made significant investment in staff and facilities and a far-reaching reorganisation of estates and infrastructure.