Short Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dermestid Beetles (Dermestes Maculatus)

Care guide Dermestid Beetles (Dermestes maculatus ) Adult beetle and final instar larva pictured Dermestid Beetles (also known as Hide Beetles) are widespread throughout the world. In nature they are associated with animal carcasses where they arrive to feed as the carcass is in the latter stages of decay. They feed on the tough leathery hide, drying flesh and organs, and will eventually strip a carcass back to bare bone. Due to their bone cleaning abilities they are used by museums, universities and taxidermists worldwide to clean skulls and skeletons. Their diet also has made them pests in some circumstances too. They have been known to attack stored animal products, mounted specimens in museums, and have caused damage in the silk industry in years gone by. The adult beetles are quite small and the larger females measure around 9mm in body length. Adult beetles can fly, but do so rarely. The larvae are very hairy and extremely mobile. Both the adults and larvae feed on the same diet, so can be seen feeding side by side at a carcass. Each female beetle may lay hundreds of tiny eggs, and are usually laid on or near their food source. The larvae go through five to 11 stages of growth called instars. If conditions are not favourable they take longer to develop and have more instars. Due to their appetite for corpses at a particular stage of decay, these beetles have forensic importance and their presence and life stage can aid forensic scientists to estimate the time of death, or the period of time a body has been in a particular place. -

Powder As an Eco-Friendly Management of Skin Beetle Dermestes Maculatus (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) in Atlantic Codfish Gadus Morhua (Gadiformes: Gadidae)

Asian Journal of Advances in Agricultural Research 13(3): 47-56, 2020; Article no.AJAAR.56841 ISSN: 2456-8864 Insecticidal Property of Black Seed (Nigella sativa) Powder as an Eco-friendly Management of Skin Beetle Dermestes maculatus (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) in Atlantic Codfish Gadus morhua (Gadiformes: Gadidae) Bob-Manuel, R. Bekinwari1 and Ukoroije, R. Boate2* 1Department of Biology, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education Rumuolumeni, Port Harcourt. P.M.B. 5047, Rivers Sate, Nigeria. 2Department of Biological Sciences, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, P.O.Box 071, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors compiled the literature search, assembled, proofread and approved the work. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJAAR/2020/v13i330108 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Daniele De Wrachien, The State University of Milan, Italy. Reviewers: (1) Shravan M. Haldhar, India. (2) Adeyeye, Samuel Ayofemi Olalekan, Ton Duc Thang University, Vietnam. (3) Destiny Erhabor, University of Benin, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/56841 Received 02 March 2020 Accepted 09 May 2020 Original Research Article Published 27 June 2020 ABSTRACT The bio-pesticidal potential of Nigella sativa seed powder in the management of Dermestes maculatus in codfish (Gadus morhua) was evaluated in the laboratory. D. maculatus beetles were obtained from naturally infested smoked fish, cultured at ambient temperature for the establishment of new stock and same age adults. Purchased N. sativa seeds were ground into fine powder, weighed at 0.4 g, 0.8 g, 1.2 g, 1.6 g and 2.0 g for use in the bioassay. -

From Guatemala

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2019 A contribution to the knowledge of Dermestidae (Coleoptera) from Guatemala José Francisco García Ochaeta Jiří Háva Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. December 23 2019 INSECTA 5 ######## A Journal of World Insect Systematics MUNDI 0743 A contribution to the knowledge of Dermestidae (Coleoptera) from Guatemala José Francisco García-Ochaeta Laboratorio de Diagnóstico Fitosanitario Ministerio de Agricultura Ganadería y Alimentación Petén, Guatemala Jiří Háva Daugavpils University, Institute of Life Sciences and Technology, Department of Biosystematics, Vienības Str. 13 Daugavpils, LV - 5401, Latvia Date of issue: December 23, 2019 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL José Francisco García-Ochaeta and Jiří Háva A contribution to the knowledge of Dermestidae (Coleoptera) from Guatemala Insecta Mundi 0743: 1–5 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:10DBA1DD-B82C-4001-80CD-B16AAF9C98CA Published in 2019 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P.O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 USA http://centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non- marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. -

Hide Beetle Dermestes Maculatus Degeer1 Brianna Shaver and Phillip Kaufman2

EENY466 Hide beetle Dermestes maculatus DeGeer1 Brianna Shaver and Phillip Kaufman2 Introduction Dermestes sudanicus Gredler (1877) Dermestes truncatus Casey (1916) The hide beetle, Dermestes maculatus DeGeer, feeds on (From ITIS 2009; Hinton 1945) carrion and dry animal products. These beetles form aggregations around resources where individuals will feed and mate, attracted by pheromones secreted by males. Aggregations can vary in size, but small sources of food usually have approximately one to 13 beetles (McNamara et al. 2008). The adult beetles have forensic significance in helping to estimate the post mortem interval in suicide or homicide cases (Richardson and Goff 2001). These insects are also pests of the silk industry in Italy and India, and infest stored animal products such as dried fish, cheese, bacon, dog treats, and poultry (Veer et al. 1996, Cloud and Collinson 1986). Another beetle of both forensic and economic importance in the Dermestidae is Dermestes lardarius. This beetle can be distinguished from Dermestes maculatus as it has a yellow band of hairs on the top half of each elytron (Gennard 2007). Figure 1. Dorsal view of an adult hide beetle, Dermestes maculatus Synonymy DeGeer. Credits: Joyce Gross, University of California - Berkeley Dermestes maculatus DeGeer (1774) Dermestes vulpinus Fabricius (1781) Distribution Dermestes marginatus Thunberg (1781) Dermestes maculatus is native throughout the continental Dermestes senex Germar (1824) United States and Canada, and also Hawaii. It is also known Dermestes lateralis Sturm (1826) to occur in Oceania, southeast Asia, and Italy (Integrated Dermestes elongatus Hope (1834) Taxonomic Information System 2009, Veer et al. 1996). Dermestes lupinus Erichson (1843) Dermestes semistriatus Boheman (1851) Dermestes rattulus Mulsant and Rey (1868) 1. -

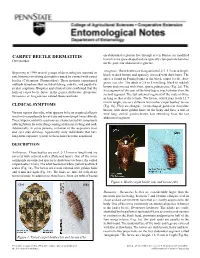

CARPET BEETLE DERMATITIS on Abdominal Segments Five Through Seven

CARPET BEETLE DERMATITIS on abdominal segments five through seven. Hastae are modified hairs that are spear shaped and are typically clumped into bunches Dermestidae on the posterior abdominal segments. Attagenus: These beetles are elongated oval, 2.5–5.5 mm in length, Beginning in 1948 several groups of dermatologists reported on black to dark brown and sparsely covered with dark hairs. The case histories involving dermatitis caused by contact with carpet species found in Pennsylvania is the black carpet beetle, Atta- beetles (Coleoptera: Dermestidae). These patients experienced genus unicolor. The adult is 2.8 to 5 mm long, black to reddish multiple symptoms that included itching, pruritic, and papulove- brown and covered with short, sparse pubescence (Fig. 2a). The sicular eruptions. Biopsies and clinical tests confirmed that the first segment of the tarsi of the hind legs is much shorter than the hairs of carpet beetle larvae in the genera Anthrenus, Attagenus, second segment. The last antennal segment of the male is twice Dermestes or Trogoderma caused these reactions. as long as that of the female. The larvae, which may reach 12.7 mm in length, are very different from other carpet beetles’ larvae CLINICAL SYMPTOMS (Fig. 1b). They are elongate, carrot-shaped, golden to chocolate brown, with short golden hairs on the body and have a tuft of Various reports describe, what appears to be an acquired allergic very long, curled, golden-brown hair extending from the last reaction to carpet beetle larval hairs and hemolymph (insect blood). abdominal segment. These hypersensitivity reactions are characterized by complaints of being bitten by something causing an intense itching and rash. -

The Infestation of Dermestes Ater (De Geer) on a Human Corpse in Malaysia

Tropical Biomedicine 26(1): 73–79 (2009) The infestation of Dermestes ater (De Geer) on a human corpse in Malaysia Kumara, T.K., Abu Hassan, A., Che Salmah, M.R. and Bhupinder, S.1 School of Biological Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Penang 1 Department of Forensic Medicine, Penang Hospital, 10990 Residensi Road, Penang Email: Received 9 January 2009, received in revised form 20 February 2009; accepted 21 February 2009 Abstract. A human corpse at an advanced stage of decomposition was found in a house in the residential area of Bukit Mertajam, Penang, Malaysia. Entomological specimens were collected during the post-mortem and the live specimens were subsequently reared at room temperature. The time of death was estimated to have been 14 days previous to the discovery of the body based on the police investigation. Both adult and larvae of the beetle Dermestes ater (De Geer) were found to be infesting the corpse and from the stage of decomposition of the body and the estimated time of death it would appear that infestation may have begun at a relatively early stage of decomposition. INTRODUCTION (Robinson, 2005). This species is cosmopolitan in distribution and appears Beetles (Coleoptera) can provide useful similar to Dermestes maculatus, but the forensic entomological evidence particularly elytra are not serrated (Byrd & Castner, with reference to dry human skeletal 2001). The larvae can be easily distinguished remains in the later stages of decomposition from others by the urogomphi that extend (Kulshrestha & Satpathy, 2001). Beetles are backward and are not strongly curved (Byrd holometabolous insects and their lifecycle & Castner, 2001). -

Coleoptera: Dermestidae) Author(S): Muñoz‐Saba, Y., Sánchez‐Nivicela, J

http://www.natsca.org Journal of Natural Science Collections Title: Cleaning Osteological Specimens with Beetles of the genus Dermestes Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) Author(s): Muñoz‐Saba, Y., Sánchez‐Nivicela, J. C., Sierra‐Durán, C. M., Vieda‐Ortega, J. C., Amat‐ García, G., Munoz, R., Casallas‐Pabón, D., *& N. Calvo‐Roa Source: Muñoz‐Saba, Y., Sánchez‐Nivicela, J. C., Sierra‐Durán, C. M., Vieda‐Ortega, J. C., Amat‐García, G., Munoz, R., Casallas‐Pabón, D., *& N. Calvo‐Roa. (2020). Cleaning Osteological Specimens with Beetles of the genus Dermestes Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Dermestidae). Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 7, 72 ‐ 82. URL: http://www.natsca.org/article/2584 NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. Muñoz-Saba, Y., et al. 2020. JoNSC. 7. pp.72-82. Cleaning Osteological Specimens with Beetles of the genus Dermestes Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) Yaneth Muñoz-Saba,1,2* Juan Carlos Sánchez-Nivicela,2,3,4 Carol M. Sierra-Durán,4 Juan Camilo Vieda-Ortega,2,4 Germán Amat-García,1 Ricardo Munoz,5 Diego Casallas-Pabón,2,6 and Nathaly Calvo-Roa2 1Institute of Natural Sciences, National University of Colombia, Bogotá D.C., Colombia 2Evolution and Ecology of Neotropical Fauna Research Group 3Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad del Ecuador, Pasaje Rumipamba 341 y Av. -

A Review of Stored-Product Entomology Information Sources

ResearcH Entomology Information Sources A Review of Stored-Product David W. Hagstrum and Bhadriraju Subramanyam ABSTRACT multibillion Thedollar field grain, of stored-product food, and retail entomology industries each deals year with through insect theirpests feeding, of raw and product processed adulteration, cereals, customer pulses, seeds, complaints, spices, productdried fruit rejection and nuts, at andthe timeother of dry, sale, durable and cost commodities. associated withThese their pests management. cause significant The reductionquantitative in theand number qualitative of stored-prod losses to the- pests is making full use of the literature on stored-product insects more important. Use of nonchemical and reduced-risk pest uct entomologists at a time when regulations are reducing the number of chemicals available to manage stored-product insect management methods requires a greater understanding of pest biology, behavior, ecology, and susceptibility to pest management methods. Stored-product entomology courses have been or are currently offered at land grant universities in four states in the United States and in at least nine other countries. Stored-product and urban entomology books cover the largest total numbers of stored-product insect species (100–160 and 24–120, respectively); economic entomology books (17–34), and popular articles or extension Web sites (29–52) cover fewer numbers of stored-product insect species. A review of 582 popular articles, 182 extension bulletins, and 226 extension Web sites showed that some aspects of stored-product entomology are covered better than others. For example, articles and Web sites on trapping (4.6%) and detection (3.3%) were more common than those on ofsampling an insect commodities pest management (0.6%). -

Two Human Cases Associated with Forensic Insects in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ⇑ Abdulmani H

Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 27 (2020) 881–886 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Original article Two human cases associated with forensic insects in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ⇑ Abdulmani H. Al-Qahtni a, Mohammed S. Al-Khalifa a, Ashraf M. Mashaly b, a Department of Zoology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box: 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia b Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Minia University, El Minia 61519, Egypt article info abstract Article history: In Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, we are reporting two cases of natural death. The two bodies showed different Received 7 November 2019 types of habitat, insect colonization and decomposition stage. The first case was about the body of a Revised 2 December 2019 65-years-old male, with mummification of the clothed body was found in an outdoor habitat. Different Accepted 18 December 2019 life stages of Dermestes maculatus DeGeer (Coleoptera: Dermestidae were gathered from the cadaver, Available online 2 January 2020 and due to the advanced degree of decomposition, the PMImin was estimated to be 3 months. The second body belonging to a 40-years-old male, was found in a semi-closed apartment (indoor habitat), and the Keywords: body was at the end of the bloated decomposition stage. In this case, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Decomposition Muscidae) larvae were collected, and the PMImin was estimated to be 4 days. The limited insect activity Forensic entomology Habitat for the two bodies caused by the advanced decomposition stage in the first case and indoor environment Human corpses in the second. -

Lesser Mealworm, Litter Beetle, Alphitobius Diaperinus (Panzer) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)1

EENY-367 Lesser Mealworm, Litter Beetle, Alphitobius diaperinus (Panzer) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)1 James C. Dunford and Phillip E. Kaufman2 Introduction Alphitobius diaperinus is a member of the tenebrionid tribe Alphitobiini (Doyen 1989), which The lesser mealworm, Alphitobius diaperinus comprises four genera worldwide (Aalbu et al. 2002). (Panzer), is a cosmopolitan general stored products Two genera occur in the United States, of which there pest of particular importance as a vector and are two species in the genus Alphitobius. There are competent reservoir of several poultry pathogens and approximately eleven known Alphitobius spp. parasites. It can also cause damage to poultry housing worldwide, and additional species are encountered in and is suspected to be a health risk to humans in close stored products (Green 1980). The other known contact with larvae and adults. Adults can become a species in the United States, A. laevigatus (Fabricius) nuisance when they move en masse toward artificial or black fungus beetle, is less commonly encountered lights generated by residences near fields where and may also vector pathogens and parasites and beetle-infested manure has been spread (Axtell occasionally cause damage to poultry housing. 1999). Alphitobius diaperinus inhabits poultry droppings and litter and is considered a significant Synonymy pest in the poultry industry. (from Aalbu et al. 2002) Numerous studies have been conducted on lesser mealworm biology, physiology, and management. Alphitobius Stephens (1832) Lambkin (2001) conducted a thorough review of Heterophaga Redtenbacher (1845) relevant scientific literature in reference to A. diaperinus and provides a good understanding of the Cryptops Solier (1851) biology, ecology and bionomics of the pest. -

Common Name: Hide Beetle Scientific Name: Dermestes Maculatus Degeer (Insecta: Coleoptera: Dermestidae)

Common name: Hide Beetle scientific name: Dermestes maculatus DeGeer (Insecta: Coleoptera: Dermestidae) Introduction The hide beetle, Dermestes maculatus DeGeer, feeds on carrion and dry animal products. These beetles form aggregations around resources where individuals will feed and mate, attracted by pheromones secreted by males. Aggregations can vary in size, but small sources of food usually have approximately one to 13. The adult beetles have forensic significance in helping to estimate the post mortem interval in suicide or homicide cases. These insects are also pests of the silk industry in Italy and India, and infest stored animal products such as dried fish, cheese, bacon, dog treats, and poultry. Another beetle of both forensic and economic importance in the Dermestidae is Dermestes lardarius. This beetle can be distinguished from Dermestes maculatus as it has a yellow band of hairs on the top half of each elytron (Gennard 2007). Figure 1. Dorsal view of an adult hide beetle, Dermestes maculatus DeGeer. Photograph by Joyce Gross, University of California – Berkeley. Distribution Dermestes maculatus is native throughout the continental United States and Canada, and also Hawaii. It is also known to occur in Oceania, Australia and southeast Asia, and Italy (Integrated Taxonomic Information System 2009, Veer et al. 1996). Description Eggs: Dermestes maculatus eggs are typically laid in batches of three to 20. The amount of eggs a single female can lay over a lifetime varies greatly, ranging from 198 to 845 Larvae: The bodies of the larvae are covered in rows of hairs of different lengths, called setae. The underside of the abdomen is typically yellowish-brown while the dorsal surface is typically dark brown, usually with a central yellow line. -

Dermestes Maculatus Infestation of Swine Barns

Dermestes maculatus infestation of swine barns. Christine Mainquist,1 BS; Josh Ellingson,1,2 DVM, MS; Kenneth Holscher,3 PhD; Locke Karriker,1 DVM, MS Diplomate, ACVPM; Jason Hocker,2 DVM, MS; Bob Blomme,2 DVM 1Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Ames, Iowa; 2AMVC Management Services, Audubon, Iowa; 3Iowa State University Department of Entomology, Ames, Iowa. Dermestes maculatus Dermestes maculatus, the hide beetle, infests and causes significant structural damage to swine barns. They tunnel out and decrease the structural integrity of wooden structures within the barns, significantly impairing their ability to maintain weight-bearing loads. Especially important in regions with heavy snowfall and damaging winds, affected barns are at a significant risk if left undiagnosed and untreated. This infestation threatens the safety of caretakers and their pigs and could be catastrophic for barn owners. Case description The first reported case by AMVC was identified in June 2008. During a routine walk-through of a finishing facility in western Iowa, small holes, approximately 0.5 cm in diameter, were discovered along the 2”x 6” uprights and brace boards. The holes created a honeycombing of the wood and fine dust was seen on the sills. The structural damage was most severe at the curtained end of the building, and there was relatively little damage closer to the exhaust fans. Larval stage of Dermestes maculatus burrowing into Upon further inspection, the holes contained small, 1cm long brown larvae. After this first case wood in a finisher building. was discovered, other finishing barns with the same management were inspected and many Dermestes maculatus enters swine barns were found to have the similar structural damage and honeycomb pattern to the wood, as well and other production animal facilities as the larvae.