The Immigration Paradox: Poverty, Distributive Justice, and Liberal Egalitarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalization, Immigration, and Education: Recent Us Trends

MASTER GABRIELLA.qxd:09_Suarez-Orozco(OK+Ale).qxd 12-12-2006 16:55 Pagina 93 Globalization and Education Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Extra Series 7, Vatican City 2006 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/es7/es7-suarezorozco.pdf GLOBALIZATION, IMMIGRATION, AND EDUCATION: RECENT US TRENDS MARCELO SUÁREZ-OROZCO, CAROLA SUÁREZ-OROZCO Over the last decade globalization has intensified worldwide economic, social, and cultural transformations. Globalization is structured by three powerful, interrelated formations: 1) the post-nationalization of produc- tion, distribution, and consumption of goods and services – fueled by grow- ing levels of international trade, foreign direct investment, and capital mar- ket flows; 2) the emergence of new information, communication, and media technologies that place a premium on knowledge intensive work, and 3) unprecedented levels of world-wide migration generating significant demographic and cultural changes in most regions of the world. Globalization’s puzzle is that while many applaud it as the royal road for development (see, for example, Micklethwait & Wooldrige, 2000; Friedman, 2000, Rubin 2002) it is nevertheless generating strong currents of discon- tent. It is now obvious that in large regions of the world, globalization has been a deeply disorienting and threatening process of change (Stiglitz, 2002; Soros, 2002; Bauman, 1998). Globalization has generated the most hostili- ties where it has placed local cultural identities, including local meaning sys- tems, local religious identities, and local systems of livelihood, under siege. Argentina is a case in point. After a decade of cutting-edge free market poli- cies, the economy of the country that once was the darling of such embodi- ments of globalization as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, imploded. -

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How Does the United States Immigration System Work?

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How does the United States immigration system work? Multiple agencies are responsible for the execution of immigration laws. o The Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) was abolished in 2003. o Department of Homeland Security . USCIS . CBP . ICE . Attorney General’s role o Department of Justice . EOIR . Attorney General’s role o Department of State . Consulates . Secretary of State’s role o Department of Labor . Employment‐related immigration Our laws, while historically pro‐immigration, have become increasingly restrictive and punitive with respect to noncitizens – even those with lawful status. ‐ Pro‐immigration history of our country o First 100 Years: 1776‐1875 ‐ Open door policy. o Act to Encourage Immigration of 1864 ‐ Made employment contracts binding in an effort to recruit foreign labor to work in factories during the Civil War. As some states sought to restrict immigration, the Supreme Court declared state laws regulating immigration unconstitutional. ‐ Some early immigration restrictions included: o Act of March 3, 1875: excluded convicts and prostitutes o Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: excluded persons from China (repealed in 1943) o Immigration Act of 1891: Established the Bureau of Immigration. Provided for medical and general inspection, and excluded people based on contagious diseases, crimes involving moral turpitude and status as a pauper or polygamist ‐ More big changes to the laws in the early to mid 20th century: o 1903 Amendments: excluded epileptics, insane persons, professional beggars, and anarchists. o Immigration Act of 1907: excluded feeble minded persons, unaccompanied children, people with TB, mental or physical defect that might affect their ability to earn a living. -

What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat

What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat Ted Brader University of Michigan Nicholas A. Valentino The University of Texas at Austin Elizabeth Suhay University of Michigan We examine whether and how elite discourse shapes mass opinion and action on immigration policy. One popular but untested suspicion is that reactions to news about the costs of immigration depend upon who the immigrants are. We confirm this suspicion in a nationally representative experiment: news about the costs of immigration boosts white opposition far more when Latino immigrants, rather than European immigrants, are featured. We find these group cues influence opinion and political action by triggering emotions—in particular, anxiety—not simply by changing beliefs about the severity of the immigration problem. A second experiment replicates these findings but also confirms their sensitivity to the stereotypic consistency of group cues and their context. While these results echo recent insights about the power of anxiety, they also suggest the public is susceptible to error and manipulation when group cues trigger anxiety independently of the actual threat posed by the group. mmigration surged onto the national agenda follow- tervals throughout U.S. history (Tichenor 2002). Current ing the 2004 election, as politicians wrangled over episodes reflect mounting pressures from heavy immi- I reforms on what is perceived to be a growing prob- gration and an expanding Latino electorate. West Europe lem for the United States (U.S.). Public concern followed, also has experienced a rising tide of migrants, spurring with 10% of Americans by 2006 naming it the most im- bitter debates over how to deal with the newcomers and portant problem facing the country, the highest level in 20 a growth in electoral position taking (Fetzer 2000; Sni- years of polling by Pew Research Center. -

Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions That Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 2020 Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions that Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes Kelly Trail Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Trail, Kelly, "Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions that Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes" (2020). Dissertations. 1809. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZATION, IMMIGRATION, AND CULTURAL CHANGE: CONDITIONS THAT PREDICT SHIFTS IN NATIONALISTIC ATTITUDES by Kelly Brannan Trail A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Social Science and Global Studies at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Robert Pauly, Committee Chair Dr. Robert Press Dr. Julie Reid Dr. Thomas Lansford August 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Kelly Brannan Trail 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Globalization is on the rise across the globe. In many instances, nationalism appears to be, too, as evidenced by the anti-immigrant and “nation first” rhetoric and success of presidential candidates, such as Donald Trump in the United States and Sebastian Pinera in Chile. However, the author questioned whether nationalistic attitudes are truly on the rise across the globe and what conditions cause some countries to shift toward nationalistic attitudes in the face of rising globalization, while others to shift away from it. -

(IOM) (2019) World Migration Report 2020

WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2020 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This flagship World Migration Report has been produced in line with IOM’s Environment Policy and is available online only. Printed hard copies have not been made in order to reduce paper, printing and transportation impacts. The report is available for free download at www.iom.int/wmr. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 Fax: +41 22 798 6150 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ISSN 1561-5502 e-ISBN 978-92-9068-789-4 Cover photos Top: Children from Taro island carry lighter items from IOM’s delivery of food aid funded by USAID, with transport support from the United Nations. © IOM 2013/Joe LOWRY Middle: Rice fields in Southern Bangladesh. -

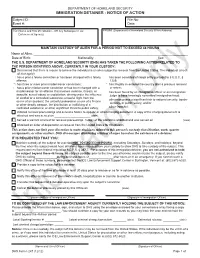

IMMIGRATION DETAINER - NOTICE of ACTION Subject ID: File No: Event #: Date

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY IMMIGRATION DETAINER - NOTICE OF ACTION Subject ID: File No: Event #: Date: TO: (Name and Title of Institution - OR Any Subsequent Law FROM: (Department of Homeland Security Office Address) Enforcement Agency) MAINTAIN CUSTODY OF ALIEN FOR A PERIOD NOT TO EXCEED 48 HOURS Name of Alien: _____________________________________________________________________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________ Nationality: __________________________________ Sex: ____________ THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY (DHS) HAS TAKEN THE FOLLOWING ACTION RELATED TO THE PERSON IDENTIFIED ABOVE, CURRENTLY IN YOUR CUSTODY: Determined that there is reason to believe the individual is an alien subject to removal from the United States. The individual (check all that apply): has a prior a felony conviction or has been charged with a felony has been convicted of illegal entry pursuant to 8 U.S.C. § offense; 1325; has three or more prior misdemeanor convictions; has illegally re-entered the country after a previous removal has a prior misdemeanor conviction or has been charged with a or return; misdemeanor for an offense that involves violence, threats, or has been found by an immigration officer or an immigration assaults; sexual abuse or exploitation; driving under the influence judge to have knowingly committed immigration fraud; of alcohol or a controlled substance; unlawful flight from the otherwise poses a significant risk to national security, border scene of an accident; the unlawful possession or use of a firearm security, or public safety; and/or or other deadly weapon, the distribution or trafficking of a other (specify): __________________________________. controlled substance; or other significant threat to public safety; Initiated removal proceedings and served a Notice to Appear or other charging document. -

Multiculturalism: Success, Failure, and the Future

MulticulturalisM: success, Failure, and the Future By Will Kymlicka TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION MULTICULTURALISM: Success, Failure, and the Future Will Kymlicka Queen’s University February 2012 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its seventh plenary meeting, held November 2011 in Berlin. The meeting’s theme was “National Identity, Immigration, and Social Cohesion: (Re)building Community in an Ever-Globalizing World” and this paper was one of the reports that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council, an MPI initiative undertaken in co- operation with its policy partner the Bertelsmann Stiftung, is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymak- ing processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Carnegie Corporation of New York, Open Society Founda- tions, Bertelsmann Stiftung, the Barrow Cadbury Trust (UK Policy Partner), the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/transatlantic. © 2012 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechani- cal, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is avail- able for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. Permission for reproducing excerpts from this report should be directed to: Permissions Department, Migra- tion Policy Institute, 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20036, or by contacting [email protected]. -

Border Security: Key Agencies and Their Missions

= 47)*7=*(:7.9>a=*>=,*3(.*8=&3)= -*.7=.88.438= -&)=_=&))&1= 3&1>89=.3= 22.,7&9.43=41.(>= 57.1=3`=,**3= 43,7*88.43&1= *8*&7(-=*7;.(*= 18/1**= <<<_(78_,4;= ,+233= =*5479=+47=43,7*88 Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress 47)*7=*(:7.9>a=*>=,*3(.*8=&3)=-*.7=.88.438= = :22&7>= After the massive reorganization of federal agencies precipitated by the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), there are now four main federal agencies charged with securing the United States’ borders: the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which patrols the border and conducts immigrations, customs, and agricultural inspections at ports of entry; the Bureau of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which investigates immigrations and customs violations in the interior of the country; the United States Coast Guard, which provides maritime and port security; and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which is responsible for securing the nation’s land, rail, and air transportation networks. This report is meant to serve as a primer on the key federal agencies charged with border security; as such it will briefly describe each agency’s role in securing our nation’s borders. This report will be updated as needed. 43,7*88.43&1=*8*&7(-=*7;.(*= 47)*7=*(:7.9>a=*>=,*3(.*8=&3)=-*.7=.88.438= = n the wake of the tragedy of September 11, 2001, the U.S. Congress decided that enhancing the security of the United States’ borders was a vitally important component of preventing I future terrorist attacks. -

Explainer: Illegal Immigration in the United States." Migration Policy Institute, April 2019

Illegal Immigration in the United States EXPLAINER By Jessica Bolter Experts inside and outside the U.S. government largely agree that there are between 11 million and 12 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States, a population that has been essentially flat for the last decade. The unauthorized population rose relatively steadily for decades until peaking at about 12 million in 2007-08, and then held steady or even fell during and after the Great Recession, based on estimates by the three organizations that regularly make these calculations: the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Pew Research Center, and the Center for Migration Studies of New U.S.York. Unauthorized Immigrant Population Estimates, 2000-17 Center for Migration Department of Homeland Year Pew Research Center Studies of New York Security 2017 10,664,000 -- -- 2016 10,812,000 -- 10,700,000 2015 11,004,000 11,960,000 11,000,000 2014 11,025,000 11,460,000 11,100,000 2013 10,991,000 11,210,000 11,200,000 2012 11,135,000 11,430,000 11,200,000 2011 11,318,000 11,510,000 11,500,000 2010 11,725,000 11,590,000 11,400,000 2009 11,899,000 10,750,000 11,300,000 2008 12,009,000 11,600,000 11,700,000 2007 11,981,000 11,780,000 12,200,000 2006 11,714,000 11,310,000 11,600,000 2005 11,317,000 10,490,000 11,100,000 2000 8,600,000 8,460,000 8,600,000 Sources: Bryan Baker, Illegal Alien Population Residing in the United States: January 2015 (Washington, DC: Department of Home- land Security, 2018), available online; Jeffrey S. -

Do Immigrants Threaten US Public Safety?

Do Immigrants Threaten U.S. Public Safety? Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny Working Paper 1905 Research Department https://doi.org/10.24149/wp1905 Working papers from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas are preliminary drafts circulated for professional comment. The views in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Do Immigrants Threaten U.S. Public Safety?* Pia Orrenius† and Madeline Zavodny‡ August 2019 Abstract Opponents of immigration often claim that immigrants, particularly those who are unauthorized, are more likely than U.S. natives to commit crimes and that they pose a threat to public safety. There is little evidence to support these claims. In fact, research overwhelmingly indicates that immigrants are less likely than similar U.S. natives to commit violent and property crimes, and that areas with more immigrants have similar or lower rates of violent and property crimes than areas with fewer immigrants. There are relatively few studies specifically of criminal behavior among unauthorized immigrants, but the limited research suggests that these immigrants also have a lower propensity to commit crime than their native- born peers, although possibly a higher propensity than legal immigrants. Evidence about legalization programs is consistent with these findings, indicating that a legalization program reduces crime rates. Meanwhile, increased border enforcement, which reduces unauthorized immigrant inflows, has mixed effects on crime rates. A large-scale legalization program, which is not currently under serious consideration, has more potential to improve public safety and security than several other policies that have recently been proposed or implemented. -

Primer on U.S. Immigration Policy

Primer on U.S. Immigration Policy Updated July 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45020 SUMMARY R45020 Primer on U.S. Immigration Policy July 1, 2021 U.S. immigration policy is governed largely by the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which was first codified in 1952 and has been amended significantly several times since. U.S. William A. Kandel immigration policy contains two major aspects. One facilitates migration flows into the United Analyst in Immigration States according to principles of admission that are based upon national interest. These broad Policy principles currently include family reunification, U.S. labor market contribution, origin-country diversity, and humanitarian assistance. The United States has long distinguished permanent from temporary immigration. Permanent immigration occurs through family and employer-sponsored categories, the diversity immigrant visa lottery, and refugee and asylee admissions. Temporary immigration occurs through the admission of foreign nationals for specific purposes and limited periods of time, and encompasses two dozen categories that include foreign tourists, students, temporary workers, and diplomats. The other major aspect of U.S. immigration policy involves restricting entry to and removing persons from the United States who lack authorization to be in the country, are identified as criminal aliens, or whose presence in the United States is determined to not serve the national interest. Such immigration enforcement is broadly divided between border enforcement—at and between U.S. land, air, and sea ports of entry—and other enforcement tasks including interior enforcement, detention, removal, worksite enforcement, and combatting immigration fraud. The dual role of U.S. immigration policy—admissions and enforcement—creates challenges for balancing major policy priorities, such as ensuring national security, facilitating trade and commerce, protecting public safety, and fostering international cooperation. -

International Migration: the Human Face of Globalisation Summary in English

International Migration: The human face of globalisation Summary in English Drawing on the unique expertise of the OECD, this book moves beyond rhetoric to look at the realities of international migration today: Where do migrants come from and where do they go? How do governments manage migration? How well do migrants perform in education and in the workforce? And does migration help – or hinder – developing countries? About 190 million people around the world live outside their country of birth. These migrants bring energy, entrepreneurship and fresh ideas to our societies. But there are downsides: young migrants who fail in education, adults who don’t find work and, of course, unregulated migration. Such challenges can make migration a political lightning rod and a topic for angry debate. INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION: THE HUMAN FACE OF GLOBALISATION ISBN 978-92-64-047280 © OECD 2009 – 1 Few issues excite controversy like international migration, in part because it touches on so many other questions – economics, demographics, politics, national security, culture, language and even religion. That combination only adds to the complexity of designing policies that maximise the benefits of migration for the countries where migrants settle, those they leave behind and for migrants themselves. Overcoming these difficulties is essential, however, in large part because migration is a constant of human history: People have always sought new and better homes, and will continue to do so. Further, many countries will need to go on attracting immigrants in the years to come as they cope with population ageing and seek to fill gaps in their labour forces. And countries with existing large immigrant communities will also need to find ways to improve the track record of migrants in areas like education and employment.