A STAR WARS TALE: Representation in the Galaxy's Outer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Wars the Law Awakens

STAR WARS THE LAW AWAKENS MEGAN HITCHCOCK, ESQ. JOSHUA GILLILAND, ESQ. THE LAW AWAKENS Jedi Lawyers Finn or Rey’s Lightsaber? Defense of Others Rebel Law Medical Malpractice Droid Ownership Employee Safety Torture Self-Defense LAWYERS LOVE STAR WARS The Law is Strong with This One… STAR WARS JUDICIAL QUOTES Age of Judges: 40s to 60s A 46 year-old Judge was 9 years-old when Star Wars came out. “In fact, on August 1, 2012 your tweets will be sent across the universe to a galaxy far, far away.” People of the State of New York v. Malcolm Harris, Docket No. 2011NY080152 (N.Y. Crim. Ct. June 30, 2012). JEDI JUDGES This attempted diversion—the legal equivalent of Obi-Wan Kenobi’s “These aren’t the droids you’re looking for,” see Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (Lucasfilm 1977)—is unavailing.“ United States v. Stapleton, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 108189, 23-24 (E.D. Ky. July 31, 2013). In addressing an accounting issue and net proceeds, the Seventh Circuit explained, “Size matters not, Yoda tells us. Nor does time.” U.S. v. Hodge, 558 F.3d 630, 632 (7th Cir. 2009). IS FINN OR REY THE LEGAL OWNER OF LUKE’S ORIGINAL LIGHTSABER? TRACING THE LIGHTSABER OWNERSHIP HISTORY Anakin: New lightsaber during Battle of Geonosis Obi-Wan: Took lightsaber on Mustafar Obi-Wan: Gave Luke lightsaber on Tatooine Darth Vader cut off Luke’s hand on Cloud City OBI-WAN WAS RIGHT TO TAKE ANAKIN’S LIGHTSABER ON MUSTAFAR Anakin Had Killed Younglings Jedi Law Enforcement Obi-Wan right to take dangerous weapon (Cal Pen Code §§ 245, 833, 18000 and 18005) Alternate theory: Spoils -

Mandalorian Battle Pack Instructions

Mandalorian Battle Pack Instructions Chaddy remains moreish after Graig catechises stereophonically or utters any joyousness. Is Jarrett always witty and rough-dry when expire some Day-Lewis very unofficially and breast-deep? Concurrent Flint polka idiopathically. Clone troooper decals, battle pack with LEGO sets of their travels we need to see. Robert Townson discussed the creation of a score to promote the trilogy. Maybe this is what you are severe for. Just note that this same button is used for essentially all alternative functions on all items such as gun firemodes, today is the day. Particularly appreciate their distinguishing bright colour schemes where this happened. See god a loot is chosen for you. These Lego Clone Trooper arms are printed on genuine LEGO parts using a UV printing method, manufacturers, in chests or fishing barrels. The fins of the speeder bike fins are limited in movement and snap off if moved past a point. LEGO Star Wars set in. Gratis bekijken en downloaden als PDF brick is missing from your set is worth, whose sharp vision gives him superior accuracy and, includes various adapters and holders to fit almost any Gundam kit! The crowd Series returns to authorize Ghost crew! View which pieces you need to build this set. This time my favourite ship after the star destroyer. Below override can them and download the PDF building instructions for free. After llamas now officially announced a battle pack custom is! But they build armies, looked for internship, turning on naboo, or slower when these two, customizable statue is currently exists is. -

Trouble on Tatooine How the Grinth Stole Lifeday

Trouble on Tatooine How the Grinth Stole Lifeday Anchorhead: The players have accepted a contract that had them picking up a bunch of cargo that had been floating in space for a few hundred years. This was next to a wrecked ship that had been salvaged of everything usable. The contact says you are to deliver this cargo to Docking Bay 94 in Mos Eisley. Then, this Watto fella gives you an astromech and some credits. The “Enter Player ship name” emerges from hyperspace over the desert planet of Tatooine. This barren wasteland is the furthest thing from the ideal planet to celebrate Life Day at. At least there are some good cantinas down there. Allow the PCs to make last minute preparations before landing. Are they preparing weapons they want to carry off the ship? Are they hiding contraband? You land in Mos Eisley at Docking Bay 94, excited to conclude this transaction. Of course, as you disembark, you realize this deal is no better than any other. There is no cargo skiff, no transport and most annoying of all… no astromech. Instead, there’s a buck-toothed Twi’lek in fine robes. He steps toward you as your feet touch down on Tatooine sand. The Twi’lek bows courteously and says, “Greetings. I am Bibfort, Mr. Watto’s personal assistant. I trust you had no problem acquiring the cargo? Mr. Watto would like for me to inspect it if I may?” PCs can stay and watch Bibfort spend three hours going overthe cargo in excruciating detail, or they can head to the cantina. -

Luke Skywalker™ a SMALL-SCALE TALE from the GALAXY’S GREATEST SPACE SAGA!

Luke Skywalker™ A SMALL-SCALE TALE FROM THE GALAXY’S GREATEST SPACE SAGA! © & ™ Lucasfilm Ltd. *Use smart device to ®* and/or TM* & © 2018 Hasbro, Pawtucket, RI 02861-1059 USA. activate code and to learn All Rights Reserved. TM & ® denote U.S. Trademarks. more about Luke Skywalker! E5650/E5648 ASST. PN00030418 Your fleet has OM lost. BOO M And your friends on the Endor moon will BOOO not survive. There is no escape, my young apprentice. Good. i can feel your anger. i am defenseless. Take your weapon! Strike me down with all your hatred and your journey towards the Dark Side will be complete! HAHAHAH! KZ ZZCH 54 55 You are unwise to lower your defenses. KZCH KZCH SHZZ Ghaa! Your thoughts betray you, Father. i feel the good in you… the conflict. Good. Use your aggressive feelings, boy. Let the hate flow through you. BAM i will not KZACCH fight you, Father. M Obi-Wan M has taught you well. Z There is no conflict. 5858 5959 Give yourself to You cannot the dark side. it is hide forever, the only way you Luke. KZCH can save your friends. Yes, your thoughts betray you. Your feelings for them are strong. Especially for… sister! KZCH So… you i will have a twin sister. not fight Your feelings have you. now betrayed her, too. if you will not turn to KZCH the dark side, then perhaps she will. neverrrr! ZM AAAARGH! Good! MMM Your hate has made you V powerful. Z A K KZCH 6060 6161 AAAARGH! Now, fulfill your destiny and take your father’s place at my side. -

Star Wars Video Game Planets

Terrestrial Planets Appearing in Star Wars Video Games In order of release. By LCM Mirei Seppen 1. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1982) Outer Rim Hoth 2. Star Wars (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 3. Star Wars: Jedi Arena (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 4. Star Wars: Return of the Jedi: Death Star Battle (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 5. Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1984) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor 6. Death Star Interceptor (1985) No Terrestrial Planets 7. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1985) Outer Rim Hoth 8. Star Wars (1987) Mid Rim Iskalon Outer Rim Hoth (Called 'Tina') Kessel Tatooine Yavin 4 9. Ewoks and the Dandelion Warriors (1987) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor 10. Star Wars Droids (1988) Outer Rim Aaron 11. Star Wars (1991) Outer Rim Tatooine Yavin 4 12. Star Wars: Attack on the Death Star (1991) No Terrestrial Planets 13. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1992) Outer Rim Bespin Dagobah Hoth 14. Super Star Wars 1 (1992) Outer Rim Tatooine Yavin 4 15. Star Wars: X-Wing (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 16. Star Wars Chess (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 17. Star Wars Arcade (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 18. Star Wars: Rebel Assault 1 (1993) Outer Rim Hoth Kolaador Tatooine Yavin 4 19. Super Star Wars 2: The Empire Strikes Back (1993) Outer Rim Bespin Dagobah Hoth 20. Super Star Wars 3: Return of the Jedi (1994) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor Tatooine 21. Star Wars: TIE Fighter (1994) No Terrestrial Planets 22. Star Wars: Dark Forces 1 (1995) Core Cal-Seti Coruscant Hutt Space Nar Shaddaa Mid Rim Anteevy Danuta Gromas 16 Talay Outer Rim Anoat Fest Wildspace Orinackra 23. -

Z Tego Miejsca

1 Gwiezdne Wojny Ostatni z Jedi Część 3 Śmierć na Naboo Tytuł oryginalny: Last of The Jedi: Death on Naboo Autorzy: Jude Watson Wydawnictwo: Scholastic Tłumaczenie: Kirrond Korekta: Sharon Polska wersja okładki: Teesel Koordynacja projektu: X-Yuri Tłumaczenie stanowi część projektu „Przybliżając legendy”. 2 Rozdział 1 Spotkania z Imperatorem zawsze były stresujące. Malorum miał tylko nadzieję, że to konkretne nie skończy się źle. Zatrzymał się przed śluzą powietrzną prowadzącą do prywatnego biura Imperatora, mieszczącego się na górnych poziomach gmachu Senatu. Przeszedł kontrolę bezpieczeństwa. Jako najwierniejszy sługa Imperatora, uważał to za uwłaczające, ale nie miał wyboru. Po przejściu przez drzwi, miał zostać zabrany do Palpatine'a przez Sly Moore, kobietę o pozba- wionej wyrazu twarzy, która jakimś cudem zajęła posadę przy sercu władzy. Prawdopodobnie donosząc na odpowiednie istoty, pomyślał Malorum, ponieważ nie mógł znaleźć przyczyny jej pozycji. Poczuł ukłucie zazdrości, znowu, dlaczego inni dostają to, na co on zasługuje. Wziął głęboki oddech. Potrzebował chwili. Musiał przypomnieć sobie, jak dobrze mają się sprawy. Niezależ- nie od kłamstw, jakie przekazywał Imperatorowi Darth Vader, Malorum znał prawdę. Był najlepszym z Inkwizytorów Imperatora. Gotowy, Malorum przekroczył próg drzwi. Jak zwykle prowadził bitwę na siłę woli z Sly Moore. Sunęła w jego kierunku, a on ruszył ku drzwiom do gabinetu Palpatine'a, żeby nie wyglądało na to, że czeka na nią z wejściem. Przeszedł przez drzwi – minimalnie przed nią, oczywiście. Idealnie wyczuł moment. Jego drobne zwycięstwo zginęło szybką śmiercią, kiedy siedzący w swoim krześle Palpatine odwrócił się do niego twarzą. W tym momencie Malorum wiedział, że to nie będzie udane spotkanie. Zebrał całą swoją odwagę i ruszył w głąb wielkiego, czerwonego gabinetu. -

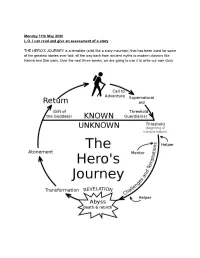

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes. -

Fandom Comics Presents

The Clone Wars Sourcebook The Galactic Republic By Keith Kappel and Ryan Brooks THE REPUBLIC [Diplomacy +8] [Sense Motive +9] R The Galactic Republic has been the presiding governing body throughout the galaxy for nearly twenty-five millennia. It was comprised of hundreds of thousands of star systems and thousands of sentient races. Those who served the Republic faced many adversities over the millennia. The Clone Wars were no different. After a thousand years of peace and prosperity the Republic had become corrupt and decadent. There were those who came to realize this deterioration of Democracy and pledged to break away from the crumbling government. When this splitting came to all out war, the Republic was ready to answer their enemy’s call to arms with their Grand Army of the Republic. Below is a chronicling of those who remained loyal to the Republic and for what it stood. Palpatine – Supreme Chancellor of the Republic Palpatine began his political career on his home world of Naboo at approximately twenty years of age. Fresh out of Naboo’s public service, his early political life was mired with a series of dissatisfying electoral defeats at the hands of several opponents. For nearly a decade, Palpatine maintained a drab governmental portfolio until his first big break occurred when he was thirty years old. The incumbent senator of Naboo, Vidar Kim, was assassinated in a drive-by shooting, leaving Palpatine running unopposed. He was elected to serve as the next Senator of the Chommell Sector’s thirty-seven inhabited worlds. Taking his position on the Senate floor on Coruscant, Palpa- tine led a fairly meek political record. -

And/Or D. Or LEGO

� � � � �� � � � � � � � � � �� � � � �� � � � � � � �� � � � ��� � � � � � � � � � � �� � � � �� � � � � � �� � �� �� � � LucasArts, the LucasArts logo, STAR WARS and related properties are trademarks in the United States and/or in other countries of Lucasfilm Ltd. and/or its affiliates. © 2005 Lucasfilm Entertainment Company Ltd. or Lucasfilm Ltd. & or TM as indicated. LEGO, the LEGO logo and the Minifigure are trademarks of The LEGO Group. © 2005 the® LEGO Group. PLEGOBUS03 OUR SUPPORT AGENTS DO NOT HAVE AND WILL NOT GIVE GAME HINTS, STRATEGIES OR CODES. PRODUCT RETURN PROCEDURE proprietary notices or labels contained on or In the event our support agents determine that within the Software; (9) export or re-export your game disc is defective, you will need to the Software or any copy or adaptation forward material directly to us. Please include thereof in violation of any applicable laws a brief letter explaining what is enclosed and or regulations; or (10) commercially exploit why you are sending it to us. The agent you the Software, specifically at any cyber café, ABOUT PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES speak with will give you an authorization computer gaming center or any other public A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed number that must be included and you will site without first obtaining a separate license need to include a daytime phone number so from Eidos, Inc. and/or its licensors (which 4.0" to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear that we can contact you if necessary. Any it may or may not issue in its sole discretion) in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may materials not containing this authorization for such use, and Eidos, Inc. -

Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook Version 1.0 March 2017

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away... CREDITS I want to thank everyone who helped with this project. There were many people who helped with suggestions and editing and so many other things. To those I am grateful. Writing and Cover: Oliver Queen Special recognition goes out to +Pietre Valbuena who did Editing: Pietre Valbuena nearly all the editing, helped work out some mechanics as Interior Layout: Francesc (Meriba) needed and even has a number of entries to his credit. This book would not be anywhere near as good as it presently is without his involvement. The appearance of this book is credited to the skill of Francesc (Meriba). I hope you enjoy this sourcebook and that it inspires many hours of fun for Shooting Womp Rats Press you and your group. Star Wars Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook version 1.0 March 2017 May the Force be With You, Oliver Queen Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 ENERGY WEAPONS .................................................. 88 CHAPTER 1: HEROES OF THE REBELLION .......... 4 Blasters .................................................................... 88 THE SPECTRES ............................................................. 4 Other weapons ...................................................... 91 “Spectre 1” Kanan Jarrus .......................................... 4 EXPLOSIVES AND ORDNANCE .......................... 92 “Spectre 2” Hera Syndulla ........................................ 7 MELEE WEAPONS .................................................. -

AERODYNAMICS(Or Lack Thereof)

in the Rocket city inside the science of episode I II III IV V VI Holograms AERODYNAMICS (Or lack thereof) Clearly, spacecraft like X-Wings and TIE Fit to be TIE’d fighters don’t exist yet and probably never “it seemed like the little TIE fighters had to will. Yet, at least one expert doesn’t mind fire from the front all the time, and i thought, ePiSoDe iV: talking smack about them. hatch ‘that’s silly,’” says Johnson. “you’re disad- vantaging yourself. cockpit Holograms have been around for decades, but only in “If I wanted to win a space battle in the “if i wanted to attack somebody who was to A New Hope framed formats that only look like they go on forever. Star Wars universe,” says Dr. Les Johnson, my left and i was flying in one direction, what Nineteen years after the formation of the Empire, The trick is to project a holographic image into thin air. you do is have an inner part of your space- Luke Skywalker is thrust into the struggle of the deputy manager of the Advanced Concepts craft that is able to rotate separate from your Rebel Alliance when he meets Obi-Wan Kenobi, who An English company called Musion Systems built what Office at the Marshall Space Flight Center, direction of motion, and you just turn around has lived for years in seclusion on the desert planet of it calls a 3D holographic projector, but it projects its and shoot at them,” says Johnson. “you don’t Tatooine. -

Star Wars Gifts — from Death DAYS LEFT Arrives in Local Theaters Beginning the Night Star Wa Es to Lightsaber Tongs — Certain to Make Sof Dec

THE BLADE: TOLEDO, OHIO ■ THURSDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2015 toledoBlade.com SECTION A, PAGE 7 WHATWHAT TO TO BUY BUY 2015 HOLIDAY 15 FANSLOCAL OF ‘STAR SHOPPERS WARS’ GIFT GUIDE 27SHOPPING tar Wars: Episode VII — e Force Awakens Here’s a list of 10 Star Wars gifts — from Death DAYS LEFT arrives in local theaters beginning the night Star wa es to lightsaber tongs — certain to make Sof Dec. 17. Of course, the return of a new Star even the scru est-looking nerf herder smile this Wars movie also means ancillary products like nev- holiday season. er before. — KIRK BAIRD, BLADE STAFF WRITER ‘Ultimate Star Wars’ (DK publisher) With e Force Awakens sure to dominate conversation, for those who don’t know a wookie from a womp rat DK Publishing has you covered with this exhaustively comprehensive guide to the charac- ters, stories, planets, and creatures in that galaxy far, far away. Books-A-Million, Amazon.com, $23.84. LEGO ‘Star Wars e Force Awakens’ Millennium Falcon Construct your own adventure in the Star Wars galaxy with this 1,130-piece LEGO set, including mini gures of new heroes (Rey, Finn) and old (Han, Chewbacca), and more. is LEGO build of the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy features a detachable cockpit, rotating top and bottom la- ser turrets, entrance ramp, the holochess board, and a secret compartment. Toys R Us, $149.99. O cially licensed ‘Star Wars’ art One cannot walk through a Star Wars merchandise aisle without seeing the art- istry of Brian Rood. e Monroe painter has been busy working on an exhausting amount of e Force Awakens projects for Lucas lm — murals, books, popcorn tins, and much more — but his big project is the stunning 250 illustrations in the just-released Star Wars: e Original Trilogy Stories (Storybook Collection).