Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management: Development and Field Application, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Southern Vietnam

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 10, October 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 4686-4694 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d211030 Biology, morphology and damage of the lesser Coconut weevil, Diocalandra frumenti (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in southern Vietnam HONG-UNG NGUYEN1,, THI-HIEN NGUYEN1, NGUYEN-QUOC-KHANH CHAU2, VAN-VANG LE2, VAN-HAI TRAN2 1Department of Agriculture and Aquaculture, Tra Vinh University. No. 126, Nguyen Thien Thanh Street, Ward 5, Tra Vinh City, Viet Nam Tel.: +84-94-3855692, email: [email protected], [email protected]. 2College of Agriculture, Can Tho University. No. 3/2 Street, Ninh Kieu District, Can Tho City, Viet Nam Manuscript received: 14 July 2020. Revision accepted: 20 September 2020. Abstract. Nguyen HU, Nguyen TH, Chau NQK, Le VV, Tran VH. 2020. Biology, morphology and damage of the lesser coconut weevil, Diocalandra frumenti (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in southern Vietnam. Biodiversitas 21: 4686-4694. The lesser coconut weevil, Diocalandra frumenti, is an emerging pest of coconut trees in Vietnam. To help develop control options for D. frumenti, this study investigated its morphological and biological characteristics, and quantified damage levels on coconut trees. Results from the study showed that attack by D. frumenti on coconut trees is correlated with characteristic damage symptoms (e.g., oozing sap) on all maturity stages of coconut fruits throughout the year (24.7% infestation), with higher damage levels on young fruits (57.6%). Results also showed that infestation levels on trees (58.9%), coconut bunches (19.4%), and fruits (7.77%) varied greatly. Adults have four different morphologies, but genetic study showed that they are all one species. -

Document Downloaded From: This Paper Must Be Cited As

Document downloaded from: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/101790 This paper must be cited as: The final publication is available at http://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc6b04829 Copyright American Chemical Society Additional Information This document is the Accepted Manuscript version of a Published Work that appeared in final form in Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, copyright © American Chemical Society after peer review and technical editing by the publisher. To access the final edited and published work see http://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc6b04829 1 Identification of the Male-Produced Aggregation Pheromone of the Four-Spotted 2 Coconut Weevil, Diocalandra frumenti 3 4 Sandra Vacas,†* Ismael Navarro,‡ Elena Seris,§ Carina Ramos,§ Estrella Hernández,# 5 Vicente Navarro-Llopis,† Jaime Primo† 6 7 †CEQA-Instituto Agroforestal del Mediterráneo, Universitat Politècnica de València, 8 Camino de Vera s/n, edificio 6C-5ª planta, 46022 Valencia (Valencia), Spain. 9 ‡Ecología y Protección Agrícola SL, Pol. Ind. Ciutat de Carlet, 46240 Carlet (Valencia), 10 Spain. 11 §Dirección General de Agricultura – Gobierno de Canarias, 38003 Santa Cruz de 12 Tenerife (Tenerife), Spain. 13 #ICIA-Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias, Ctra. de El Boquerón s/n Valle 14 Guerra, 38270 La Laguna (Tenerife), Spain. 15 16 * Corresponding author (Tel: +34963879058; Fax: +34963879059; E-mail: 17 [email protected]) 18 19 1 20 ABSTRACT 21 The four-spotted coconut weevil, Diocalandra frumenti Fabricius (Coleoptera: 22 Curculionidae), is a small weevil found attacking economically important palm species 23 such as coconut, date, oil and Canary palms. Given the scarcity of detection and 24 management tools for this pest, the availability of a pheromone to be included in 25 trapping protocols would be a crucial advantage. -

Diocalandra Frumenti.Pdf (Consultado El 11 De Marzo De 2018)

Evaluación de productos comerciales con Beauveria bassiana para el control del picudo de las cuatro manchas del cocotero (Diocalandra frumenti Fabricius) en condiciones de laboratorio Se autoriza la reproducción, sin fines comerciales, de este trabajo, citándolo como: Ramos Cordero, C.; Perera González, S.; Piedra-Buena Díaz, A. 2018. Evaluación de productos comerciales con Beauveria bassiana para el control del picudo de las cuatro manchas del cocotero (Diocalandra frumenti Fabricius) en condiciones de laboratorio. Informe Técnico Nº 2. Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias. 17 pág. Este trabajo ha sido desarrollado dentro del convenio establecido entre el Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias y la empresa Glen Biotech S.L. Colección Información técnica Nº 2 Autores: Carina Ramos Cordero, Santiago Perera González, Ana Piedra-Buena Díaz Edita: Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias, ICIA. Maquetación y diseño: Fermín Correa Rodríguez (ICIA)© Impresión: Imprenta Bonnet S.L. ISSN 2605-2458 “Evaluación de productos comerciales con Beauveria bassiana para el control del picudo de las cuatro manchas del cocotero (Diocalandra frumenti Fabricius) en condiciones de laboratorio” RAMOS CORDERO, C. (1); PERERA GONZÁLEZ, S. (2); PIEDRA-BUENA DíAZ, A. (1) 1. Área de Entomología. Departamento de Protección Vegetal. Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias. 2. Unidad de Experimentación y Asistencia Técnica Agraria. Servicio Técnico de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Cabildo Insular de Tenerife. Resumen El picudo de las cuatro -

RHYNCHOPHORINAE of SOUTHEASTERN POLYNESIA1 2 (Coleoptera : Curculionidae)

Pacific Insects 10 (1): 47-77 10 May 1968 RHYNCHOPHORINAE OF SOUTHEASTERN POLYNESIA1 2 (Coleoptera : Curculionidae) By Elwood C. Zimmerman BISHOP MUSEUM, HONOLULU Abstract: Ten species of Rhynchophorinae are recorded from southeastern Polynesia, including two new species of Dryophthorus from Rapa. Excepting the latter, all the spe cies have been introduced into the area and most are of economic importance. Keys to adults and larvae, notes on biologies, new distributional data and illustrations are pre sented. This is a combined Pacific Entomological Survey (1928-1933) and Mangarevan Expedi tion (1934) report. I had hoped to publish the account soon after my return from the 1934 expedition to southeastern Polynesia, but its preparation has been long delayed be cause of my pre-occupation with other duties. With the exception of two new endemic species of Dryophthorus, described herein, all of the Rhynchophorinae found in southeastern Polynesia (Polynesia south of Hawaii and east of Samoa; see fig. 1) have been introduced through the agencies of man. The most easterly locality where endemic typical rhynchophorids are known to occur in the mid- Pacific is Samoa where there are endemic species of Diathetes. (I consider the Dryoph- thorini and certain other groups to be atypical Rhynchophorinae). West of Samoa the subfamily becomes increasingly rich and diversified. There are multitudes of genera and species from Papua to India, and it is in the Indo-Pacific where the subfamily is most abundant. Figure 2 demonstrates the comparative faunistic developments of the typical rhynchophorids. I am indebted to the British Museum (Natural History) for allowing me extensive use of the unsurpassed facilities of the Entomology Department and libraries and to the Mu seum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, for use of the library. -

Cria Diocalandra Frumenti.Pdf

Estudio de la metodología de cría de Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius, 1801) (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae) Se autoriza la reproducción, sin fines comerciales, de este trabajo, citándolo como: Estévez Gil, J.R.; Hernández Suárez, E.; Seris Barrallo, E. 2018. Estudio de la metodología de cría de Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius, 1801) (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae). Información Técnica Nº 4. Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias. 16 págs. Agradecimientos Servicio de Sanidad Vegetal. Dirección General de Agricultura. Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Aguas del Gobierno de Canarias. D. Pedro Sosa Henríquez (Foto tomada en La Cogolla, Mogán, Gran Canaria). Por foto de portada. Colección Información técnica Nº 4 Autores: José Ramón Estévez Gil, Estrella Hernández Suárez, Elena Seris Barrallo Edita: Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias, ICIA. Maquetación y diseño: Fermín Correa Rodríguez (ICIA)© Impresión: Imprenta Bonnet S.L. ISSN 2605-2458 Estudio de la metodología de cría de Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius, 1801) (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae) 1Estévez Gil, José Ramón; 1Hernández Suárez, Estrella; 1*Seris Barrallo, Elena 1Departamento de Protección Vegetal del Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias de la Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Aguas del Gobierno de Canarias 1.- Introducción Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius, 1801) (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae) como especie alóctona en las Islas Canarias, supone una grave amenaza para la familia Arecaceae, con especial referencia a la palmera canaria, Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. Además, se trata de una amenaza para especies de palmeras del resto de España y países europeos. La EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization) hasta 2011 la incluía en la lista de alerta para la Unión Europea, donde se categorizaba como plaga de cuarentena (EPPO, 2011). -

Diocalandra Frumenti

Diocalandra frumenti Boletín 4 INTRODUCCIÓN Diocalandra frumenti es un escarabajo de pequeñas dimensiones (aprox. 5 mm), que se detecta por primera vez en Canarias en Marzo de 1998 en ejemplares de palmera canaria (Phoenix canariensis) en Maspalomas, isla de Gran Canaria. Posteriormente se ha detectado en las islas de Fuerteventura, Lanzarote y más recientemente en la isla de Tenerife, situándose los focos en la zona de Los Cristianos, Candelaria, Valle de Guerra y Santiago del Teide. Para intentar evitar su dispersión, la Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación a publicado la Orden de 29 de Octubre de 2007 (BOC nº 222, de 6 de Noviembre), en la se establecen mediBIOLOGÍAdas fitosanitarias para su control. CICLO BIOLÓGICO La biología de la Diocalandra es poco conocida pero en las condiciones del archipiélago canario las generaciones se suceden ininterrumpida- mente a lo largo de todo el año y la duración del ciclo completo (huevo-adulto) es de 2,5 – 3 meses. El ciclo de vida de este coleóptero presenta 4 fases: Huevo, larva, pupa y adulto. El huevo no es fácil de ver y tienen forma ovalada, color brillante semi-transparente con tamaño entorno a 1 mm. Los huevos son depositados por las hembras, mediante su ovipositor, de manera aislada. Las larvas al emerger son de color amarillento, sin patas, alargadas, segmentadas y con una cabeza en- durecida de color amarilla-marrón, provisto de unas fuertes mandíbulas cónicas. Al final de la fase larvaria, tras 8 a 10 semanas, puede llegar a tener 6 - 8 mm de longitud. Las larvas se alimentan del tejido vegetal interno de la palmera y como consecuencia de esta acción deja una serie de galerías internas, causando en esta etapa el mayor daño a la palmera. -

Download Download

Trapping-a major tactic of BIPM strategy of palm weevils S. P. Singh¹ and P. Rethinam¹ Abstract Several species of curculionid weevils such as Amerrhinus ynca Sahlberg, Cholus annulatus Linnaeus, C. martiniquensis Marshall, C. zonatus (Swederus), Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius), Dynamis borassi Fabricius, Homalinotus coriaceus Gyllenhal, Metamasius hemipterus Linnaeus, Paramasius distortus (Gemminger & Horold), Rhabdoscelus obscurus (Boisduval), Rhinostomus barbirostris (Fabricius), R. afzelii (Gyllenhal), Rhynchophorus bilineatus (Montrouzier), R. cruentatus Fabricius, R. ferrugineus (Olivier), R. palmarum (Linnaeus) and R. phoenicis (Fabricius) are associated with palms. Some of these have become a major constraint in the successful cultivation of coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L.), date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) and oil palm (Elaeis guineensis L.). R. ferrugineus is distributed in over 33 countries and attacks more than two dozen palm species. In the recent past, it has spread to Middle Eastern countries, Mediterranean region of Africa and southern Europe (Spain) causing tremendous economic losses. The yield of date palm has decreased from 10 to 0.7 tons/ha. Coconut palms in India are infested upto 6.9 per cent in Kerala and 11.65 per cent in Tamil Nadu. R. palmarum is a major pest of oil and coconut palms in the tropical Americas and, vectors the nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus (Cobb) Baujard which causes red ring disease (RRD). Palm losses due to RRD are commonly between 0.1 to 15% which amounts to tens of millions dollars. The status of other species is briefed. The grubs of weevils that develop in the stems, bud, rachis of leaves and inflorescence of cultivated, ornamental or wild palms cause direct damage. -

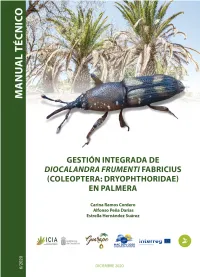

Manualtecnicodiocalandra.Pdf

GESTIÓN INTEGRADA DE DIOCALANDRA FRUMENTI FABRICIUS (COLEOPTERA: DRYOPHTHORIDAE) EN PALMERA Prólogo Podríamos convenir que la palmera canaria, Phoenix canariensis, se sitúa en la cúspide vegetal del ecosistema del bosque termófilo de las zonas medias y bajas de la mayoría de las Islas Canarias, junto con otras especies que son representativas del mismo, como el drago, el cardón, el acebuche, la sabina o el almácigo, por citar algunas. Todas ellas están adaptadas en mayor o menor medida al ambiente árido que caracteriza este piso de vegetación. La palmera canaria se sitúa preferentemente en los surcos que la erosión ha convertido en barrancos y barranquillos, y su poderoso sistema de raíces aprovecha las aguas subálveas que las escasas lluvias aportan y quedan en la parte baja de esos valles. La relativa mayor disponibilidad de agua, unido a su poderoso aparato fotosintético, la convierten en un gran aportador de biomasa con consecuencias ecológicas, y en ciertos casos, económicas, entre las que cabe mencionar su aportación a conformar paisajes únicos y de gran belleza, o la peculiar industria de la mal llamada “miel de palma”, desarrollada sobre todo en la isla de La Gomera. La belleza de la palmera canaria, unido a su relativa facilidad de crecimiento y multiplicación, ha convertido a la especie en una de las más utilizadas y reconocidas como ornamentales, sobre todo en las zonas de clima mediterráneo o similar en numerosas partes del mundo. La profusa utilización como planta de jardinería de la especie, unido a la gran producción de savia azucarada por esa gran capacidad fotosintética, también la convierte en diana de posibles huéspedes inconvenientes. -

Caractérisation Et Phylogénie Des Bactéries Symbiotiques Intracellulaires Des Charançons De La Famille Des Dryophthoridae

N° d’ordre 04 ISAL 007 Année 2004 THESE Caractérisation et phylogénie des bactéries symbiotiques intracellulaires des charançons de la famille des Dryophthoridae présentée devant L’INSTITUT NATIONAL DES SCIENCES APPLIQUEES DE LYON pour obtenir le grade de docteur Ecole doctorale : Evolution, Ecosystèmes, Microbiologie et Modélisation Specialité : Analyse et Modélisation des Systèmes Biologiques par Cédric LEFEVRE soutenue le 10 février 2004 devant la Commission d’examen Jury : E.J.P. DOUZERY Rapporteur A. LATORRE Rapporteur J.C. SIMON Rapporteur W. NASSER Président A. HEDDI Directeur H. CHARLES Co-Directeur Laboratoire de Biologie Fonctionelle, Insectes et Interactions UMR INRA/INSA de Lyon Bât L. Pasteur, 20 Avenue A. Einstein 69621 Villeurbanne Cedex France Novembre 2003 INSTITUT NATIONAL DES SCIENCES APPLIQUEES DE LYON Directeur : STORCK A. Professeurs : AMGHAR Y. LIRIS AUDISIO S. PHYSICOCHIMIE INDUSTRIELLE BABOT D. CONT. NON DESTR. PAR RAYONNEMENTS IONISANTS BABOUX J.C. GEMPPM*** BALLAND B. PHYSIQUE DE LA MATIERE BAPTISTE P. PRODUCTIQUE ET INFORMATIQUE DES SYSTEMES MANUFACTURIERS BARBIER D. PHYSIQUE DE LA MATIERE BASKURT A. LIRIS BASTIDE J.P. LAEPSI**** BAYADA G. MECANIQUE DES CONTACTS BENADDA B. LAEPSI**** BETEMPS M. AUTOMATIQUE INDUSTRIELLE BIENNIER F. PRODUCTIQUE ET INFORMATIQUE DES SYSTEMES MANUFACTURIERS BLANCHARD J.M. LAEPSI**** BOISSE P. LAMCOS BOISSON C. VIBRATIONS-ACOUSTIQUE BOIVIN M. (Prof. émérite) MECANIQUE DES SOLIDES BOTTA H. UNITE DE RECHERCHE EN GENIE CIVIL - Développement Urbain BOTTA-ZIMMERMANN M. (Mme) UNITE DE RECHERCHE EN GENIE CIVIL - Développement Urbain BOULAYE G. (Prof. émérite) INFORMATIQUE BOYER J.C. MECANIQUE DES SOLIDES BRAU J. CENTRE DE THERMIQUE DE LYON - Thermique du bâtiment BREMOND G. PHYSIQUE DE LA MATIERE BRISSAUD M. -

PESTS of the COCONUT PALM Mi Pests and Diseases Are Particularly Important Among the Factors Which Limit Agricultural Production and Destroy Stored Products

PESTS of the COCONUT PALM mi Pests and diseases are particularly important among the factors which limit agricultural production and destroy stored products. This publication concerns the pests of the coconut palm and is intended for the use of research workers, personnel of plant protection services and growers Descriptions are given for each pest (adult or early stages), with information on the economic importance of the species the type of damage caused, and the control measures which have been applied (with or without success) up to the present time. The text deals with 110 species of insects which attack the palm in the field; in addition there arc those that attack copra in storage, as well as the various pests that are not insects This is the first of a series of publications on the pests and diseases of economically importani plants and plant products, and is intended primarily to fill a gap in currently available entomological and phytopathological literature and so to assist developing countries. PESTS OF THE COCONUT PALM Copyrighted material FAO Plant Production and Protection Series No. 18 PESTS OF THE COCONUT PALM b R.J.A.W. Lever FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome 1969 Thl 6 One 0A8R-598-HSG9 First printing 1969 Second printing 1979 P-14 ISBN 92-5-100857-4 © FAO 1969 Printed in Italy Copyrighted material FOREWORD Shortage of food is still one of the most pressing problems in many countries. Among the factors which limit agricultural production and destroy stored products, pests and diseases are particularly important. -

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES 11-16939 WPPR Point 9.4 Report of a Pest Risk Analysis for Diocalandra frumenti This summary presents the main features of a pest risk analysis which has been conducted on the pest, according to EPPO Decision support scheme for quarantine pests. Pest: Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius) PRA area: The PRA area is the EPPO region (see map www.eppo.org). Assessors: A preliminary draft has been prepared by Elford Stuart Cooper Smith1. This document has been reviewed by an Expert Working Group composed by, Antonio Gonzalez Hernandez4, Dirk Jan van der Gaag2, Jose Maria Guitián Castrillon3, Francisco Javier Garcia Domínguez4, Rosa Martin Suarez5, Jorge Peña6, Francesco Salomone Suarez7, Elford Stuart Cooper Smith1. 1 Biosecurity and Product Integrity Division, Department of Primary Industry, Fisheries and Mines, GPO Box 3000, 0801 Darwin, Northern Territory (AU) 2 Plant Protection Service, P.O. Box 9102, 6700 HC Wageningen, The Netherlands 3 Tecnologias y Servicios Agrarios, S. A. - TRAGSATEC, C / Hnos. Garcia Noblejas, 37C. 2a Planta, 280037 Madrid (ES) 4 Direccion General de Agricultura, Servicio de Sanidad Vegetal, Avda. José Manuel Guimeré, 8, 38003 Santa Cruz de Tenerife (ES) 5 Sanidad Vegetal, Direccion General de Agricultura, Edificio Iberia, C/Agustin Millares Carlo, 10 Planta 3, 35071 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands (ES) 6 Entomology and Nematology, Tropical Research and Education Center, 18905 SW 280th Street, FL 33031 Homestead (US) 7 Servicio de Parques y Jardines, Col N° 3521, Jefe de la Seccion de Medioambiente y Servicios Municipales, Ayutamiento de, San Cristobal de la Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands (ES) Date: Expert Working Group in 2008-12. -

Diocalandra Frumenti (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), Nueva Plaga De Palmeras Introducida En Gran Canaria

Bol. San. Veg. Plagas, 28: 347-355, 2002 Diocalandra frumenti (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), nueva plaga de palmeras introducida en Gran Canaria. Primeros estudios de su biología y cría en laboratorio M. GONZÁLEZ NÚÑEZ, A. JIMÉNEZ ÁLVAREZ, F. SALOMONE, A. CARNERO, P. DEL ESTAL, J.R. ESTEBAN DURÁN Diocalandra frumenti, curculiónido plaga de palmeras en diversas áreas litorales de los océanos Pacífico e índico, ha sido recientemente introducido en la Isla de Gran Ca- naria, constituyendo un claro peligro para la palmera Canaria y otras palmáceas. En este trabajo se presentan los resultados obtenidos con distintos métodos de cría en laborato- rio ensayados. Utilizando fragmentos de caña de azúcar, sobre la que se colocaban 10 parejas de adultos durante una semana, se obtuvo una media de 4,2 adultos por caña, con una duración del desarrollo de 7,8 días para los huevos, de 76,2 días para la larva y de 10,2 días para la pupa. Mediante la utilización de 4 diferentes dietas artificiales se obtuvieron porcentajes de supervivencia de 0%, 15,6%, 11,1% y 37,8% y una duración del periodo larvario de 73,2, 69,2 y 60,9 días. M. GONZÁLEZ NÚÑEZ, A. JIMÉNEZ ÁLVAREZ, J.R. ESTEBAN DURAN: Departamento de Protección Vegetal. INIA. Carretera de La Corana Km 7,5. 28040-Madrid. F. SALOMONE: Departamento de Ornamentales y Horticultura. ICIA. Valle de Gue- rra, La Laguna. 28200-Tenerife. A. CARNERO: Departamento de Protección Vegetal. ICIA. Valle de Guerra, La La- guna. 28200-Tenerife. P. DEL ESTAL: Unidad de Protección de Cultivos. E.T.S.I.Agrónomos.