Capsule Wardrobe’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, to the Record of Protected Structures in Accordance with Section 54 and 55 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (As Amended)

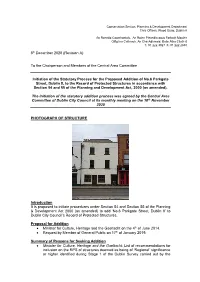

Conservation Section, Planning & Development Department Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 An Rannóg Caomhantais, An Roinn Pleanála agus Forbairt Maoine Oifigí na Cathrach, An Ché Adhmaid, Baile Átha Cliath 8 T. 01 222 3927 F. 01 222 2830 8th December 2020 (Revision A) To the Chairperson and Members of the Central Area Committee Initiation of the Statutory Process for the Proposed Addition of No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, to the Record of Protected Structures in accordance with Section 54 and 55 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (as amended). The initiation of the statutory addition process was agreed by the Central Area Committee of Dublin City Council at its monthly meeting on the 10th November 2020 PHOTOGRAPH OF STRUCTURE Introduction It is proposed to initiate procedures under Section 54 and Section 55 of the Planning & Development Act 2000 (as amended) to add ‘No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8’ to Dublin City Council’s Record of Protected Structures. Proposal for Addition Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht on the 4th of June 2014. Request by Member of General Public on 17th of January 2019. Summary of Reasons for Seeking Addition Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht: List of recommendations for inclusion on the RPS of structures deemed as being of ‘Regional’ significance or higher identified during Stage 1 of the Dublin Survey carried out by the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. No.6 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8, together with the neighbouring properties at Nos.7 and 8 Parkgate Street, Dublin 8 has been assigned a ‘Regional’ rating. -

Pear 40Plusstyle Ebook with Page Numbers

‹#› 40+Style The complete guide for dressing the pear body shape ‹› Welcome to this special guide by 40plusstyle.com where we celebrate style and beauty of women over 40 and 40plusstylecourses.com where we teach you how to get more style. My name is Sylvia, creator of both sites and I believe that we should have FUN with style & fashion. I feel that personal style advances as we age as we become ever more aware of what suits our personality, our body and our life. I also believe in personal style that is unique to YOU. I feel that when you find the style that suits you, you will feel happier and more confident living your life. I know that many of you struggle with dressing your unique body so this guide is for you. It will give you some ps and tricks that make dressing your body type easier, so you feel happier and more confident! Please note that these are guidelines only and you can break them as you please! Enjoy this special guide! 2 ‹› the complete guide for dressing the pear body shape 3 ‹› First, Determine which body shape you are 4 Determine which body shape you are There are several types: Let’s have a look at 5 basic female body shapes. There are several ways to define your body shape. •Hourglass c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s o f P e a r s h a p e •Inverted triangle • Your hips are wider than your shoulder •Pear (also called triangle or spoon) • Fat tends to accumulate on your thighs and sometimes the buttocks •Rectangle (also called ruler or banana) • You tend to have an elongated waist and the legs tend to be •Apple (also called cone or downwards shorter in comparison to the 5rest of your body triangle) • You have a defined waist Determining your body shape with measurements: If you know the measurements of your bust, waist and hips you can also use this online calculator which will give you a general idea. -

SOHO Design in the Near Future

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 12-2005 SOHO design in the near future SooJung Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Lee, SooJung, "SOHO design in the near future" (2005). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Imaging Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts SOHO Design in the near future By SooJung Lee Dec. 2005 Approvals Chief Advisor: David Morgan David Morgan Date Associate Advisor: Nancy Chwiecko Nancy Chwiecko Date S z/ -tJ.b Associate Advisor: Stan Rickel Stan Rickel School Chairperson: Patti Lachance Patti Lachance Date 3 -..,2,2' Ob I, SooJung Lee, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Signature SooJung Lee Date __3....:....V_6-'-/_o_6 ____ _ Special thanks to Prof. David Morgan, Prof. Stan Rickel and Prof. Nancy Chwiecko - my amazing professors who always trust and encourage me sincerity but sometimes make me confused or surprised for leading me into better way for three years. Prof. Chan hong Min and Prof. Kwanbae Kim - who introduced me about the attractive -

Closet Staples Casual Capsule Wardrobe Builder

CLOSET STAPLES CASUAL CAPSULE WARDROBE BUILDER SHOPPING LIST SHOPPING LIST Tops: Jackets/Sweaters: Gray T-Shirt (Spring/Summer/Fall) Denim Jacket (Spring/Summer/Fall) Striped Long Sleeve Shirt (Spring/Fall/Winter) Gray Cardigan (Spring/Fall/Winter) Navy Sweater (Spring/Fall) Utility Jacket (Spring/Fall) Chambray Button Down (Spring/Summer/ Beige Cardigan (Spring/Fall/Winter) Fall/Winter) Bright Cardigan (Spring/Summer) White Tank Top (Spring/Summer) Black Parka (Winter) Floral Top (Spring/Summer/Fall) Wool Coat (Winter) White T-Shirt (Spring/Summer/Fall/Winter) Navy T-Shirt (Summer) Striped Short Sleeve Shirt (Summer) Cream Pullover Sweater (Fall/Winter) Shoes: Choose the type of shoes that work best for your lifestyle. Gray Pullover Sweater (Fall/Winter) Black Turtleneck Sweater (Winter) Gold Sandals (Spring/Summer) Gold Sneakers (Spring/Summer) Leopard Flats (Spring/Fall) Leopard Sneakers (Spring/Summer/Fall) Bottoms: Leopard Booties (Winter) Olive Jeans (Spring) Taupe Ankle Boots (Spring/Fall) Olive Shorts (Summer) Neutral Wedges (Spring/Summer) White Jeans (Spring) Yellow Sandals (Summer) White Shorts (Summer) Black Ankle Boots (Fall/Winter) Blush Jeans (Spring) - Optional Cognac Riding Boots (Fall/Winter) You may substitute light wash jeans or a Black Winter Boots (Winter) different colored denim. Boyfriend Jeans (Spring) Boyfriend Shorts (Summer) Gray Jeans (Fall/Winter) Accessories: Burgundy Jeans (Fall/Winter) Leopard Belt (Spring/Fall/Winter) Black Jeans (Fall/Winter) Black Purse (Spring/Fall/Winter) Dark Wash Jeans (Fall/Winter) -

Architectural Access Board 1/27/06 521

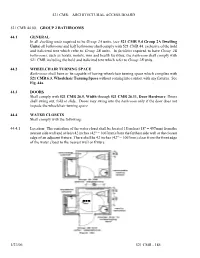

521 CMR: ARCHITECTURAL ACCESS BOARD 521 CMR 44.00: GROUP 2 BATHROOMS 44.1 GENERAL In all dwelling units required to be Group 2A units, (see 521 CMR 9.4 Group 2A Dwelling Units) all bathrooms and half bathrooms shall comply with 521 CMR 44, exclusive of the bold and italicized text which refer to Group 2B units. In facilities required to have Group 2B bathrooms, such as hotels, motels, inns and health facilities, the bathroom shall comply with 521 CMR including the bold and italicized text which refer to Group 2B units. 44.2 WHEELCHAIR TURNING SPACE Bathrooms shall have or be capable of having wheelchair turning space which complies with 521 CMR 6.3, Wheelchair Turning Space without coming into contact with any fixtures. See Fig. 44a. 44.3 DOORS Shall comply with 521 CMR 26.5, Width through 521 CMR 26.11, Door Hardware. Doors shall swing out, fold or slide. Doors may swing into the bathroom only if the door does not impede the wheelchair turning space. 44.4 WATER CLOSETS Shall comply with the following: 44.4.1 Location: The centerline of the water closet shall be located 18 inches (18" = 457mm) from the nearest side wall and at least 42 inches (42" = 1067mm) from the farthest side wall or the closest edge of an adjacent fixture. There shall be 42 inches (42" = 1067mm) clear from the front edge of the water closet to the nearest wall or fixture. 1/27/06 521 CMR - 185 521 CMR: ARCHITECTURAL ACCESS BOARD 44.00: GROUP 2 BATHROOMS 44.4.2 Height: The top of the water closet seat shall be 15 inches to 19 inches (15" to 19" = 381mm to 483mm) above the floor. -

Residential Square Footage Guidelines

R e s i d e n t i a l S q u a r e F o o t a g e G u i d e l i n e s North Carolina Real Estate Commission North Carolina Real Estate Commission P.O. Box 17100 • Raleigh, North Carolina 27619-7100 Phone 919/875-3700 • Web Site: www.ncrec.gov Illustrations by David Hall Associates, Inc. Copyright © 1999 by North Carolina Real Estate Commission. All rights reserved. 7,500 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $.000 per copy. • REC 3.40 11/1/2013 Introduction It is often said that the three most important factors in making a home buying decision are “location,” “location,” and “location.” Other than “location,” the single most-important factor is probably the size or “square footage” of the home. Not only is it an indicator of whether a particular home will meet a homebuyer’s space needs, but it also affords a convenient (though not always accurate) method for the buyer to estimate the value of the home and compare it to other properties. Although real estate agents are not required by the Real Estate License Law or Real Estate Commission rules to report the square footage of properties offered for sale (or rent), when they do report square footage, it is essential that the information they give prospective purchasers (or tenants) be accurate. At a minimum, information concerning square footage should include the amount of living area in the dwelling. The following guidelines and accompanying illustrations are designed to assist real estate brokers in measuring, calculating and reporting (both orally and in writing) the living area contained in detached and attached single-family residential buildings. -

Storage Closet

WRD-01272 WRD-01518 60" wide double door storage closet 64 in H x 60 in W x 19.7 in D (163 cm H x 152.4 cm W x 50 cm D) www.honeycando.com | [email protected] | 877.2.I.can.do (877.242.2636) IMPORTANT! Plead read prior to use. This Honey-Can-Do 60 inch Wide Double Door Storage Closet is designed for indoor use. Please do not over-load. To prevent tipping, we recommend that you evenly distribute the weight throughout the unit. Please keep top hanger bar horizontal when in use. Please do not use storage closet for anything other than its intended use. Please do not allow children, husbands or pets to hang from or hide in storage closet. Please keep away from heat sources such as heaters and fireplaces. 2 PARTS LIST PART/ILLUSTRATION (QTY) DESCRIPTION (6) side supports (these holes Do Not pass all the way through support) (3) middle supports (these holes pass all the way through support) (5) tapered supports bars (12) uprights E (5) support bars F (1) cover G (1) tapered hang bar (1/8" thicker than support bar) H (1) hang bar (1/8" thicker than support bar) Thank you for purchasing a Honey-Can-Do Storage Closet! Please follow these step by step instructions carefully. Plan to spend about 35 minutes assembling your new closet. For assistance, please contact us at [email protected] or 877.2.i.Can.Do. Your closet will hold up to 50lbs when hangers are evenly distributed across the unit. -

A Place for Everything in Your Saint Louis Closet Co

Spring 2015 Cooking up Something Super for Your Pantry Second to the master closet, pantries are on the top of homeowners’ lists to organize with customized shelving and accessories; this is no surprise since the kitchen is often considered “the heart of the home.” Where does everyone wind up at a party…in the kitchen. According to Closets Magazine, when touring model homes, visitors spend more time in the kitchen than any other room in the home. Saint Louis Closet Co. has noticed that with the increase in popularity of purchasing in bulk from large box stores, there is more and more focus on storage of foods, paper goods, and even excess dishes and appliances. Saint Louis Closet Co. custom closets can truly make a difference in your pantry. Maximizing your kitchen pantry with corner shelving, platter dividers and adjustable shelving for the varied size items stored in pantries can make overall kitchen storage simpler. Chrome pull-out wine racks store wine bottles at a 15-degree angle to ensure corks remain moist in storage. Pull-out chrome baskets in various sizes are perfect for paper goods, chips, and recycling. And don’t forget tray shelves and basket-rimmed shelves for canned goods and small boxes. Once you’ve realized there’s a place for everything in your Saint Louis Closet Co. pantry…then everything will be in its place in your kitchen! Saint Louis Closet Co. offers free in-home design consultations for all areas of your home. Call us at (314) 781-9000 or visit us online at www.stlouisclosetco.com. -

Proper Wardrobe Storage & Preservation Do's and Don'ts From

Proper Wardrobe Storage & Preservation Do’s and Don’ts from the Experts at Garde Robe So, you have the walk-in closet you always dreamed of and assembled an impeccable collection of priceless vintage, haute couture, evening wear, footwear and accessories. Now, how do you go about protecting your precious wardrobe and keeping items in pristine condition? Never store your wardrobe in: • Basements, attics or closets where the temperature and humidity levels are inconsistent • Closed closets in your second or infrequently visited home • Closets that have an outside wall (these closets tend to have higher relative humidity) • Near a window with sunlight • Plastic or vinyl bags Your wardrobe’s worst enemies are changes in temperature, sunlight, moisture and material-damaging insects such as clothes moths. Heat - Particularly a problem for garments made from animal skins and furs. These fabrics require the natural oil to remain supple and prevent degradation and loss of integrity of the skin. Dry skins will eventually break down and becoming weakened and split. Sunlight - Dye fading. The first color to fail will be any dye with purple including many blue garments. Sun fading can happen in as short a time as a few hours. Be careful when hanging a jacket in the back of a car to prevent over exposure. Moisture = mold and mildew. Closets are generally dark places with little air movement. Add moisture and this is the perfect environment for the growth of mildew. Be sure to air out items that may have been subjected to high relative humidity before returning back to your closet. -

Spring Capsule Wardrobe SPRING CAPSULE WARDROBE SPRING CAPSULE WARDROBE

spring capsule wardrobe SPRING CAPSULE WARDROBE SPRING CAPSULE WARDROBE Thank you so much for downloading the Spring 2021 Capsule Wardrobe! In this latest capsule you’ll discover 21 versatile pieces styled into over 100 outfits. Everything in this PDF is shoppable - just click the product image in each collage! Like my previous capsules, this one is full of pieces you likely already own - a denim jacket, white jeans, neutral bags and shoes, etc! TRENCH COAT MOTO JACKET DENIM JACKET WHITE SHIRTDRESS PRINTED MINIDRESS While you might pick up a few new pieces for the spring season, I’m hoping this capsule wardrobe will inspire you to shop your own closet and get more use out of pieces you’ve already purchased... especially since a lot of us aren’t shopping as much thanks to the SWEATSHIRT SWEATER WHITE SHIRT PRINTED BLOUSE WHITE TEE pandemic! Use this capsule wardrobe to get more creative with what you’ve got, and feel free to tailor it to your location and lifestyle. For example: If you live somewhere super cold, you might swap out the heeled sandals for ankle boots! If you are BLUE JEANS WHITE JEANS LEGGINGS living in athleisure looks, swap out the skirt for MIDI SKIRT another pair of leggings in a complimentary hue. I did my best to incorporate inclusive sizing and a wide variety of price points, but you can find some additional suggestions for all budgets and sizes at the back of this PDF (starting on page 37)! Lots of cute pieces to consider there. TOTE BACKPACK SHOULDER BAG Thank you again for downloading and I hope you enjoy this latest capsule! Whether you plan to shop or not, your support means the world. -

Wfw19-Magazine-2

Apr/May 2019 WINCHESTER FASHION WEEK Complimentary #WFW19 Programme of Talks Workshops Showcases Shopping Experiences #INDIEWINCH EDIT Winchester’s fashion independents on Instagram Sponsored by Brought to you by @WinFashionWk A CELEBRATION OFwinchesterfashionweek.co.uk STYLE FREE FILM SCREENING The University of Winchester is proud to sponsor Winchester Fashion Week 2019 and to host a special free screening of an acclaimed fashion documentary that delves behind the scenes of 2015’s China-themed Met Gala, the fashion world’s most dynamic annual event. THE FIRST MONDAY IN MAY Hello & Welcome, e are delighted to warmly welcome you to the ninth annual Winchester Fashion Week coordinated by Winchester Business Improvement District (BID). W It’s lovely to meet you. Let’s start with the introductions… We are Sarah and Hannah from Winchester BID, who have worked together to produce and promote this year’s event. We are proud to present a fresh, new theme and programme for Winchester Fashion Week – A Celebration Of Style (WFW19). This includes in store shopping experiences, workshops, talks and showcases, as well as catwalk shows and a fashion fair. This year, we have revised and developed WFW19 to celebrate style in the city. We have introduced a new brand that pays homage to its heritage with a focus on sustainability, local charity and the city’s circular economy throughout the event. This year, we have revised and developed the 6 day event, which we see as a great way to bring local businesses together with some exciting collaborations, interesting presentations and to showcase all things new on offer in Winchester, whilst building subjects like sustainability, local charity and the city’s circular economy into the proceedings. -

Closet Systems Add Value and Style the Easy Way

CLOSET SYSTEMS ADD VALUE AND STYLE THE EASY WAY RubbermaidPro.com Rubbermaid Limited Lifetime Warranty Rubbermaid manufactures durable, high-quality merchandise. We warrant that, when professionally installed, our closet and garage systems are free of defects in materials or workmanship for life. MAKE A SMALL CHANGE FOR A BIG IMPACT Today’s demanding consumers want the most for their money. Closet upgrades offer homeowners a big value for a small investment. From basic to beautiful, Rubbermaid has the storage products homeowners want, and we also have the selling tools you need to satisfy your customers effortlessly. • Master bedroom retreats • Standard walk-in closets • Highly functional pantries • Traffic-ready mudrooms It’s so simple to create the ideal storage solution that will make a big impact on your business and your customers’ satisfaction. Rubbermaid is a Builder Brand Leader in Closet/Organization Systems Made in the USA BASIC WIRE Storage for Every Space The epoxy-coated wire shelving is: Rubbermaid’s basic white wire shelving is • Constructed from industrial-grade steel designed to provide sturdy storage options • Smooth with a glass-like finish that prevents dust buildup for every area of the home. • Virtually maintenance-free Good Options: Linen Shelving – A standard way to store folded clothing Wardrobe Shelving – A standard solution for hanging clothes and common household goods. in bedrooms and laundry areas. ADVANCED WIRE Functional Style For just a little bit more than the cost of a basic wire closet, consumers can enjoy greater style and functionality – and more value. Today’s homeowners want pantries that complement their new stainless steel appliances and closets that embrace trendy hardware that’s now standard in most new homes.