Cowper's Stock Buckle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miller Duraflex Harnesses Feel the Difference with Specially-Formulated Elastomer (Stretchable) Webbing!

Middle East / India Product Family Miller DuraFlex Harnesses Feel the difference with specially-formulated elastomer (stretchable) webbing! Product Numbers & Ordering Information Product Numbers Details E552/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, mating buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E850-7/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, mating buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E850-58/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, tongue buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E570/S/MRN DuraFlex "Ms. Miller" Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulders, mating buckle chest and leg straps, sliding back D-ring, back pad, leg pads, and lanyard ring - Small/Medium E570/URN DuraFlex "Ms. Miller" Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulders, mating buckle chest and leg straps, sliding back D-ring, back pad, leg pads, and lanyard ring - universal E650/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and mating buckle legs straps - universal Page 1 of 5 © Honeywell International Inc. Miller DuraFlex Harnesses E650-4/S/MGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and tongue buckle legs straps - Small/Medium E650-4/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and tongue buckle legs straps - universal E650-4/XXLGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and tongue buckle -

Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design

Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design: Merchandising 1 correspondence courses and/or community college courses is an TEXTILES, MERCHANDISING effective way to demonstrate one’s commitment to academic success. & FASHION DESIGN: Transferring from Other Colleges within the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Students transferring to the College of Education and Human Sciences MERCHANDISING from another University of Nebraska–Lincoln college or from the Exploratory and Pre-Professional Advising Center must have a minimum Description cumulative GPA of 2.0, be in good academic standing, and meet the The merchandising option is planned for those students interested in the freshman entrance requirements that exist at the time of their admission buying and selling of textile and apparel products at the manufacturing to the College of Education and Human Sciences. Students must fulfill and retail levels, as well as product development, promotion, and degree requirements that exist at the time of their admission to the visual merchandising. The program emphasizes textiles and product college, not at the time they enter the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. development and provides an understanding of fashion theory, as well as basic skills and techniques in the apparel and textiles industry and To remain current, College of Education and Human Sciences students distribution of textiles and apparel in the global society. must enroll in, and complete, at least one university course that will apply toward degree requirements during a 12-month period. Students who readmit following an absence of one year or more must meet all College Requirements requirements in the Undergraduate Catalog in effect at the time of College Admission readmission and enrollment. -

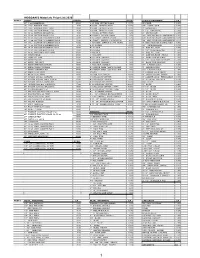

WEBPRICES 2020-MATERIALS Website

HOGGAN’S Materials Price List 2020 PAGE 1 FABRIC YRD/EA ZIPPERS FT/EA PLASTIC HARDWARE EA 46" 9 oz.SUMBRELLA 40.00 # 4.5 COIL ZIPPER CHAIN 0.75 ZIPCORD 0.50 36" 10oz. BANNER VINYL 7.00 # 5 COIL ZIPPER CHAIN 0.80 1/8" CORD LOCK 0.60 36" 13oz. BANNER VINYL (BO) 10.00 # 8 COIL ZIPPER CHAIN 0.90 1" GM BUCKLE 1.50 36" 10 oz. COTTON SINGLE FILL 4.00 # 9 COIL ZIPPER CHAIN 1.00 1 - 1/2" GM BUCKLE 2.00 36” 12 oz. COTTON SINGLE FILL 5.00 # 10 COIL ZIPPER CHAIN 1.20 2" GM BUCKLE 2.50 48" 15 oz. COTTON SINGLE FILL 6.00 # 5 TOOTH ZIPPER CHAIN 1.00 1/2“ SIDE RELEASE CONTOURED 0.50 60” 12 oz. COTTON 12 NUMBER DUCK 14.00 # 10 TOOTH ZIPPER CHAIN 1.25 5/8" SIDE RELEASE CONTOURED 0.60 48" 15 oz. COTTON 10 NUMBER DUCK 11.00 # 5 TOOTH ZIPPER CHAIN METAL 2.00 3/4“ SIDE RELEASE CONTOURED 0.75 84" 15oz. COTTON 10 NUMBER DUCK 16.00 # 10 TOOTH ZIPPER CHAIN METAL 3.50 1” SIDE RELEASE CONTOURED 0.90 36" 18 oz. COTTON 8 NUMBER DUCK 8.00 # 4.5 SLIDER 0.50 3/4" SIDE RELEASE 0.75 60” 24 oz. COTTON 4 NUMBER DUCK 21.00 # 5 SLIDER 0.50 1" SIDE RELEASE 0.90 36" 12 oz. COTTON BOAT DUCK 13.00 # 8 SLIDER 0.50 1 - 1/2" SIDE RELEASE 1.50 60” 18 oz. COTTON CHAIR DUCK 25.00 # 9 SLIDER 0.50 2" SIDE RELEASE 2.00 60" HEATSHIELD 30.00 # 10 SLIDER 0.50 1" SIDE RELEASE HEAVY 1.50 60" LOOP VELCRO 30.00 # 5 SLIDER DOUBLE 1.00 1" DUAL SIDE RELEASE 1.00 60" MESH POCKET 16.00 # 8 SLIDER DOUBLE 1.00 1 - 1/2" DUAL SIDE RELEASE 2.00 60" MESH FISH NET 18.00 # 9 SLIDER DOUBLE 1.00 2" DUAL SIDE RELEASE 2.50 48" MESH WINDOW SCREEN 10.00 # 10 SLIDER DOUBLE 1.00 3/4" LADDER LOCK 0.50 72" MESH TENNIS SCREEN 16.00 # 5 HORSE SHOE TOOTH SLIDER 1.00 1" LADDER LOCK 0.75 72" MESH TRAMPAULINE 30.00 # 8 HORSE SHOE TOOTH SLIDER 1.00 1.5" LADDER LOCK 1.00 54" MESH 12 oz VINYL 14.00 STOPS 0.10 1" LADDER LOCK-HEAVY 1.00 72" MESH 12 oz VINYL 16.00 # 8 COIL 110" ZIPPER 18.00 1" LADDER LOCK DOUBLE 1.00 60" NYLON 200 den. -

Rags to Riches: Recycling and Upcycling Old Clothes Revised by Wendy Hamilton1

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL, CONSUMER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Rags to Riches: Recycling and Upcycling Old Clothes Revised by Wendy Hamilton1 aces.nmsu.edu/pubs • Cooperative Extension Service • Guide C-313 The College of Wish you could start with a fresh Agricultural, new wardrobe? Do you have a closet full of garments you Consumer and don’t wear anymore? With a little imagi- Environmental nation and work, you can turn those Sciences is an rags to riches! By checking your closets carefully, engine for economic you may find there is a lot more life in and community garments that have been hanging un- development in New used for some time. Although you can discard or donate Mexico, improving those garments, try giving them a the lives of New new personality by recycling them. Re- Mexicans through cycling can be a real challenge, but it’s fun and rewarding. academic, research, The type of recy- cling you decide to | Dreamstime.com © Isabel Poulin and Extension undertake will de- pend on your needs and the garment(s) you have to recycle. Ask yourself programs. the following questions: • Does the garment need minor or major repairs to become func- tional again? • Is the fabric in good condition (no pulls, worn spots, or permanent crease lines)? • Is the design of the garment suitable for recycling? Are the color, de- sign, texture, and quality of fabric fashionable and flattering for you? • Will the person for whom the garment is planned wear the garment? • Is the garment worth the effort (time and money) to recycle? New Mexico State University 1Extension Grants and Contracts Development Specialist, College of Agricultural, Consumer and aces.nmsu.edu Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University. -

DAACS Cataloging Manual: Buckles

DAACS Cataloging Manual: Buckles by Kate Grillo Jennifer Aultman and Nick Bon-Harper OCTOBER 2003 UPDATED JUNE 2012 DAACS CATALOGING MANUAL: BUCKLES INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 3 1. MAIN BUCKLE TABLE ............................................................................................. 3 1.1 Artifact Count........................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Buckle Type ........................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Completeness ........................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Buckle Frame Plating ........................................................................................... 6 1.5 Object Weight........................................................................................................ 6 1.6 Burned? ................................................................................................................. 6 1.7 Mended? ................................................................................................................ 6 1.8 Post-Manufacturing Modification ........................................................................ 7 1.9 Conservation ......................................................................................................... 7 1.10 Marks? ............................................................................................................... -

The Suit Book

THE SUIT BOOK Everything you need to know about wearing a suit CLARE SHENG First published 2018 by Independent Ink PO Box 1638, Carindale Queensland 4152 Australia Copyright © Clare Sheng 2018 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. All enquiries should be made to the author. Cover design by Alissa Dinallo Internal design by Independent Ink Typeset in 11/15 pt Adobe Garamond by Post Pre-press Group, Brisbane Cover model Lee Carseldine Styled by Elle Lavon Suit and shoes by Calibre Photography by The Portrait Store Illustrations by Jo Yu (PQ Fine Alterations) 978 0 648 2865 0 9 (paperback) 978 0 648 2865 1 6 (epub) 978 0 648 2865 2 3 (kindle) Disclaimer: Any information in the book is purely the opinion of the author based on her personal experience and should not be taken as business or legal advice. All material is provided for educational purposes only. We recommend to always seek the advice of a qualified professional before making any decision regarding personal and business needs. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book wouldn’t exist without my Mum. As a single mother, she started a clothing alterations business with very little English and hardly any money, but a lot of guts. Over the years, she worked tirelessly for 12 hours a day, seven days a week, to grow the business and put me through private school and university. -

Belts Bracelets Key Fobs a Division of Dr

BELTS BRACELETS KEY FOBS A DIVISION OF DR. DAVIES PRODUCTS CO., INC. 1318 COMMERCE PARK DRIVE WILLIAMSPORT, PA 17701 570-321-5423 800-326-9438 FAX 570-321-5426 toryleather.com [email protected] Made In The U.S.A. from American Leather -1- GETTING THE RIGHT SIZE BELT WHEN YOU CAN’T TRY IT ON USING A BELT THAT FITS TO OBTAIN THE SIZE YOU WANT • If you have a belt that fits the way you like, use it to determine the size that you need ...... Lay the belt flat and measure the distance in inches from the hole that you are using to where the belt folds around the buckle Measure between A & B for belt size A B • This number is your correct belt size. If the measurement number is an odd size, order the next even size. (if your belt measures a 31 order a 32) IF YOU DON’T HAVE A BELT THAT FITS 1. Measure your waist. This is most accurate by actually running the tape measure through your belt loops. A soft tape measure works best but any tape measure will work. 2. Make sure to measure at the waist level you intend to wear the belt. 3. This number is your correct belt size. If the measurement is an odd size, order the next even size. ( if you measure a 31, order a size 32 belt). Additional Size Check REMINDER FOR WOMEN FOR MEN ONLY USE THE MEASUREMENT ORDER A BELT THAT IS FROM THE LEVEL ON YOUR 2 INCHES LARGER WAIST THAT YOU PLAN TO THAN YOUR PANTS SIZE WEAR THE BELT -2- 3/4” YOUTH AND LADIES BELTS Whether you choose one of our belts for work, casual or dress , you will find that it will continue to look good and retains its color, shape and suppleness for many, many outings. -

Nordstrom.Com Measuring and Folding Guidelines

MEASURING AND FOLDING GUIDELINES How-to-Measure Guidelines Apparel Preparation for Measuring • Table surface must be smooth and flat. • Garment must be buttoned and/or zipped unless otherwise specified. • Garment with non-closure must be overlapped. • Gently smooth out all folds, wrinkles or creases, being careful not to stretch or distort garment. Garment Measuring • Take all measurements to the nearest 1/8” using a flexible tape measure • Be sure to indicate on the spec sheet if measurements are full or ½ • All measurements are edge to edge unless inside to inside is specified • All measurements should be taken from wearer’s left side • For curved seams, such as rises and armholes, stand tape on edge and walk along seam to be measured • For extended minimum measurements, fully extend garment until minimum extension is reached without rupturing seams or distorting garment Measurement Placement • All measurement should be taken from the middle size of the size run Term Abbreviations • BK = Back • BLW = Below • BTTN = Button • CB = Center Back • CF = Center Front • FM = From • FT = Front • HPS = High Point Shoulder • W/O = Without • W/B = Waistband • MSRMNT = Measurement • SHLDR = Shoulder • CNTR = Center • BTTM = Bottom • “V” o CF “V” neck drop is where the left and right fronts meet and create a “V”. o “V” hip measurement for pants: measure 8” down from side seam and center front to create the “V”. Measuring and Folding Guidelines 1 Tops, Blazers, Jackets, Dresses and Jumpsuits Back Length (1): Measure straight down from high point shoulder to bottom edge of garment. Shoulder (2): Measure from shoulder point to shoulder point, straight across back. -

Miller Duraflex Harnesses Feel the Difference with Specially-Formulated Elastomer (Stretchable) Webbing!

Middle East / India Partners Where To Buy Product Family Miller DuraFlex Harnesses Feel the difference with specially-formulated elastomer (stretchable) webbing! Product Numbers & Ordering Information Product Numbers Details E552/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, mating buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E850-7/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, mating buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E850-58/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps, tongue buckle leg straps and side D-rings - universal E570/S/MRN DuraFlex "Ms. Miller" Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulders, mating buckle chest and leg straps, sliding back D-ring, back pad, leg pads, and lanyard ring - Small/Medium E570/URN DuraFlex "Ms. Miller" Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulders, mating buckle chest and leg straps, sliding back D-ring, back pad, leg pads, and lanyard ring - universal E650/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and mating buckle legs straps - universal Page 1 of 5 © Honeywell International Inc. Miller DuraFlex Harnesses E650-4/S/MGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and tongue buckle legs straps - Small/Medium E650-4/UGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps and tongue buckle legs straps - universal E650-4/XXLGN DuraFlex Harness with Elastomer Webbing Friction buckle shoulder straps -

2200, Canmath 201.Qxd

Lessons 4, 5 Complete the sentences. 4. A zipper should be applied a facing has been applied, but a band has been applied to a garment. 5. Coil zippers are made of or . One advantage of them is the ease with which a stuck piece of thread or fabric may be . 6. It is best to insert a zipper when the garment sections are . Do this activity. 7. Apply a zipper to the dress you have begun by either the centered or lapped method. If you do not have a zipper the correct length, shorten a longer one as described in this lesson. Fold the tabs of the zipper under since the neckline is finished already. Lesson 5 Pockets; Seam Finishes POCKETS Patch Pockets There are many ways to make patch pock - 2. Turn the top edge of the pocket under ets. This section will explain the basics about `yI ¬¬ (1 cm), press it in place, and sew with a well-made patch pockets. The first thing to zigzag stitch. Use hem tape instead if the consider is your fabric. If it is a plaid, stripe, pocket will stretch or if you don’t have a or print, you must decide if you will match it zigzag machine. to the fabric pattern of the garment. This will determine where you will place the 3. Fold the pocket at the marks for the top pocket pattern on the fabric to cut it out. A hemline with right sides together and stitch. striped or plaid may be cut on 4. If the pocket has rounded corners at the opposite the bottom, grain or on the sew an ease bias for con - basting trast. -

WALC 9: Verbal and Visual Reasoning 3 Copyright © 2007 Linguisystems, Inc

WALC™ 9: Verbal and Visual Reasoning Workbook of Activities for Language and Cognition by Kathryn J. Tomlin Skills Ages verbal and visual reasoning 16 and up thought organization convergent reasoning Grades logic insight high school and up integration inferencing visual perception Evidence-Based Practice According to the Clinical Guidelines of The Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists (www.rcslt.org/resources, 2005) and the National Stroke Association (2006), the following therapy principles are supported: Communication, both verbal and nonverbal, is a fundamental human need. Meeting this need by facilitating and enhancing communication in any form can be vital to a patient’s well-being. Therapy should include tasks that focus on semantic processing, including semantic cueing of spoken output, semantic judgments, categorization, and word-to-picture matching. Therapy may target the comprehension and production of complex, as well as simple, sentence forms. Therapy should be conducted within natural communication environments. Rehabilitation is an important part of recovering from a stroke, and the goal is to regain as much independence as possible. This book incorporates the above principles and is also based on expert professional practice. Copyright © 2007 LinguiSystems, Inc. All of our products are copyrighted to protect the fi ne work of our authors. You may only copy the client materials needed for your own use. Any other reproduction or distribution of LinguiSystems, Inc. the pages in this book is prohibited, including copying the 3100 4th Avenue entire book to use as another source or “master” copy. East Moline, IL 61244 The enclosed CD is for your personal use and convenience. -

Exofit NEX™ Tower Climbing Harness Buckle Specifications

F a l l P r o t e c t i o n E x p e r t s Technical Bulletin No. MISC008 Subject: Buckle Specifications and Operations DBI/SALA uses four types of buckles in full body harnesses, body belts and other fall protection equipment: parachute buckles, pass through buckles, tongue buckles, and quick connect buckles. Each of these types of buckles must be adjusted to a snug fit as described in its accompanying user’s instructions to assure proper harness fit and performance. See specific product instructions for additional information on inspection, donning, use, care, and maintenance. Correct operation, materials, strength, corrosion resistance and standards for each type are listed below. Parachute Buckle Specifications Buckle Operation: The parachute buckle works by capturing the webbing between a knurled bar and the buckle frame. A spring-loaded slider bar maintains constant tension on the knurled bar. The webbing is woven into the buckle by passing the webbing up through the center slot of the buckle, over the knurled bar, then back under the outer portion of the frame, folding back on itself. At least three inches of the free end of the webbing must extend out of the buckle, when used on leg straps, to maintain a safety factor in an impact situation. Pass the free end of the strap through a web keeper to allow the webbing to lay flat and be restrained. Do not cut excess webbing off the strap. Page 1 of 5 No. MISC008 3965 Pepin Avenue ? Red Wing, MN 55066-1837 ? 651-388-8282 ? [email protected] A Member of the Capital Safety Group of Companies F a l l P r o t e c t i o n E x p e r t s Buckle Adjustment: Pulling the free end of the webbing straight out away from the buckle will increase the tension on the strap.