Shaping Rolling Circle Amplification Products Into DNA Nanoparticles by Incorporation of Modified Nucleotides and Their Applicat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanisms of Synthesis of Purine Nucleotides in Heart Muscle Extracts

Mechanisms of Synthesis of Purine Nucleotides in Heart Muscle Extracts David A. Goldthwait J Clin Invest. 1957;36(11):1572-1578. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI103555. Research Article Find the latest version: https://jci.me/103555/pdf MECHANISMS OF SYNTHESIS OF PURINE NUCLEOTIDES IN HEART MUSCLE EXTRACTS1 BY DAVID A. GOLDTHWAIT2 (From the Departments of Biochemistry and Medicine, Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio) (Submitted for publication February 18, 1957; accepted July 18, 1957) The key role of ATP, a purine nucleotide, in 4. Adenine or Hypoxanthine + PRPP -> AMP the conversion of chemical energy into mechanical or Inosinic Acid (IMP) + P-P. work by myocardial tissue is well established (1, The third mechanism of synthesis is through the 2). The requirement for purine nucleotides has phosphorylation of a purine nucleoside (8, 9): also been demonstrated in the multiple synthetic 5. Adenosine + ATP -, AMP + ADP. reactions which maintain all animal cells in the Several enzymatic mechanisms are known which steady state. Since the question immediately arises result in the degradation of purine nucleotides and whether the purine nucleotides are themselves in nucleosides. The deamination of adenylic acid is a steady state, in which their rates of synthesis well known (10): equal their rates of degradation, it seems reason- 6. AMP -* IMP + NH8. able to investigate first what mechanisms of syn- Non-specific phosphatases (11) as well as spe- thesis and degradation may be operative. cific 5'-nucleotidases (12) have been described At present, there are three known pathways for which result in dephosphorylation: the synthesis of purine nucleotides. The first is 7. -

Calcium 5'-Ribonucleotides

CALCIUM 5'-RIBONUCLEOTIDES Prepared at the 18th JECFA (1974), published in NMRS 54B (1975) and in FNP 52 (1992). Metals and arsenic specifications revised at the 57th JECFA (2001). An ADI ‘not specified’ was established at the 18th JECFA (1974). SYNONYMS Calcium ribonucleotides, INS No. 634 DEFINITION Chemical names (Mixture of) calcium inosine-5'-monophosphate and calcium guanosine-5'- monophosphate Chemical formula C10H11CaN4O8P · x H2O and C10H12CaN5O8P · x H2O Structural formula Calcium 5’-guanylate Calcium 5’-inosinate Assay Not less than 97% and not more than the equivalent of 102% of C10H11CaN4O8P and C10H12CaN5O8P, calculated on the anhydrous basis. The proportion of C10H11CaN4O8P or C10H12CaN5O8P to the sum of them is between 47% and 53%. DESCRIPTION Odourless, white or off-white crystals or powder FUNCTIONAL USES Flavour enhancer CHARACTERISTICS IDENTIFICATION Solubility (Vol. 4) Sparingly soluble in water Test for ribose (Vol. 4) Passes test Test for organic phosphate Passes test (Vol. 4) Test 5 ml of a 1 in 2,000 solution Test for inosinic acid To 2 ml of a 1 in 2,000 solution add 2 ml of 10% hydrochloric acid and 0.1 g of zinc powder, heat in a water bath for 10 min, and filter. Cool the filtrate in ice water, add 1 ml of a 3 in 1,000 sodium nitrite solution, shake well, and allow to stand for 10 min. Add 1 ml of a 1 in 200 ammonium sulfamate solution, shake well, and allow to stand for 5 min. Add 1 ml of a 1 in 500 N-(1- naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride solution. -

Effects of Allopurinol and Oxipurinol on Purine Synthesis in Cultured Human Cells

Effects of allopurinol and oxipurinol on purine synthesis in cultured human cells William N. Kelley, James B. Wyngaarden J Clin Invest. 1970;49(3):602-609. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI106271. Research Article In the present study we have examined the effects of allopurinol and oxipurinol on thed e novo synthesis of purines in cultured human fibroblasts. Allopurinol inhibits de novo purine synthesis in the absence of xanthine oxidase. Inhibition at lower concentrations of the drug requires the presence of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase as it does in vivo. Although this suggests that the inhibitory effect of allopurinol at least at the lower concentrations tested is a consequence of its conversion to the ribonucleotide form in human cells, the nucleotide derivative could not be demonstrated. Several possible indirect consequences of such a conversion were also sought. There was no evidence that allopurinol was further utilized in the synthesis of nucleic acids in these cultured human cells and no effect of either allopurinol or oxipurinol on the long-term survival of human cells in vitro could be demonstrated. At higher concentrations, both allopurinol and oxipurinol inhibit the early steps ofd e novo purine synthesis in the absence of either xanthine oxidase or hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. This indicates that at higher drug concentrations, inhibition is occurring by some mechanism other than those previously postulated. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/106271/pdf Effects of Allopurinol and Oxipurinol on Purine Synthesis in Cultured Human Cells WILLIAM N. KELLEY and JAMES B. WYNGAARDEN From the Division of Metabolic and Genetic Diseases, Departments of Medicine and Biochemistry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27706 A B S TR A C T In the present study we have examined the de novo synthesis of purines in many patients. -

Alternative Pathways of Glucose Metabolism II. Nucleotides from The

Alternative Pathways of Glucose Metabolism II . Nucleotides from the Acid-soluble Fraction of Normal and Tumor Tissues and Studies on Nucleic Acid Synthesis in Tumors*t HANNS SCHMITZ4 VAN R. POTTER, ROBERT B. HTJRLBERT,@ AND DWAIN M. WHITE (McArdie Memovial Laboratory, the Medical School, University of Wisconain, Madison, WI..) The first paper (18) in this series on the alterna MATERIALS AND METHODS tive pathways of glucose metabolism established The present study has involved the measure the fact that radioactivity from glucose-i-C'4 was ment of the specific activities of the free 5' mono-, readily incorporated into the pentose moiety of the di-, and triphosphates of adenosine, guanosine, ribonucleic and desoxyribonucleic acids of Flexner cytidine, and uridine from the acid-soluble extract Jobling tumors in rats, and described the over-all of tumor tissue in relation to the specific activities distribution of radioactivity in the acid-soluble of the corresponding nucleotides that were oh and acid-insoluble fractions of tumor and liver tis tamed by chemical or enzymatic hydrolysis of the sue at various time periods. The acid-soluble frac nucleic acids from the same tissue samples, at tion of tissue contains an appreciable amount of specified time intervals after the injection of glu free nucleotides which are possible intermediary cose-1-C'4. The experimental plan corresponds compounds in the synthesis of the nucleic acids exactly to that described in the preceding paper; (6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 16). It was noted (18) that as the C'4 many of -

Mechanism of Excessive Purine Biosynthesis in Hypoxanthine- Guanine Phosphoribosyltransferase Deficiency

Mechanism of excessive purine biosynthesis in hypoxanthine- guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency Leif B. Sorensen J Clin Invest. 1970;49(5):968-978. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI106316. Research Article Certain gouty subjects with excessive de novo purine synthesis are deficient in hypoxanthineguanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HG-PRTase [EC 2.4.2.8]). The mechanism of accelerated uric acid formation in these patients was explored by measuring the incorporation of glycine-14C into various urinary purine bases of normal and enzyme-deficient subjects during treatment with the xanthine oxidase inhibitor, allopurinol. In the presence of normal HG-PRTase activity, allopurinol reduced purine biosynthesis as demonstrated by diminished excretion of total urinary purine or by reduction of glycine-14C incorporation into hypoxanthine, xanthine, and uric acid to less than one-half of control values. A boy with the Lesch-Nyhan syndrome was resistant to this effect of allopurinol while a patient with 12.5% of normal enzyme activity had an equivocal response. Three patients with normal HG-PRTase activity had a mean molar ratio of hypoxanthine to xanthine in the urine of 0.28, whereas two subjects who were deficient in HG-PRTase had reversal of this ratio (1.01 and 1.04). The patterns of 14C-labeling observed in HG-PRTase deficiency reflected the role of hypoxanthine as precursor of xanthine. The data indicate that excessive uric acid in HG-PRTase deficiency is derived from hypoxanthine which is insufficiently reutilized and, as a consequence thereof, catabolized inordinately to uric acid. The data provide evidence for cyclic interconversion of adenine and hypoxanthine derivatives. Cleavage of inosinic acid to hypoxanthine via inosine does […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/106316/pdf Mechanism of Excessive Purine Biosynthesis in Hypoxanthine-Guanine Phosphoribosyltransferase Deficiency LEIF B. -

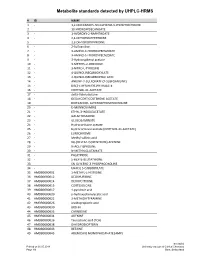

Metabolite Standards Detected by UHPLC-HRMS

Metabolite standards detected by UHPLC-HRMS #ID NAME 1 - 1,2-DIDECANOYL-SN-GLYCERO-3-PHOSPHOCHOLINE 2 - 10-HYDROXYDECANOATE 3 - 1-HYDROXY-2-NAPHTHOATE 4 - 2,4-DIHYDROXYPTERIDINE 5 - 2,6-DIHYDROXYPYRIDINE 6 - 2-Sulfoaniline 7 - 3-AMINO-4-HYDROXYBENZOATE 8 - 3-AMINO-5-HYDROXYBENZOATE 9 - 3-Hydroxyphenyl acetate 10 - 3-METHYL-2-OXINDOLE 11 - 3-NITRO-L-TYROSINE 12 - 4-QUINOLINECARBOXYLATE 13 - 4-QUINOLINECARBOXYLIC ACID 14 - ANILINE-2-SULFONATE (2-SULFOANILINE) 15 - BIS(2-ETHYLHEXYL)PHTHALATE 16 - CORTISOL 21-ACETATE 17 - delta-Valerolactone 18 - DEOXYCORTICOSTERONE ACETATE 19 - DIDECANOYL-GLYCEROPHOSPHOCHOLINE 20 - D-MANNOSAMINE 21 - ETHYL 3-INDOLEACETATE 22 - GALACTOSAMINE 23 - GLUCOSAMINATE 24 - Hydrocortisone acetate 25 - Hydrocortisone acetate (CORTISOL 21-ACETATE) 26- LUMICHROME 27 - Methyl vallinic acid 28 - N6-(DELTA2-ISOPENTENYL)-ADENINE 29 - N-ACETYLPROLINE 30 - N-METHYLGLUTAMATE 31- PALATINOSE 32 - S-HEXYL-GLUTATHIONE 33 - SN-GLYCERO-3-PHOSPHOCHOLINE 34 - URACIL 5-CARBOXYLATE 35 HMDB0000001 1-METHYL-L-HISTIDINE 36 HMDB0000012 DEOXYURIDINE 37 HMDB0000014 DEOXYCYTIDINE 38 HMDB0000015 CORTEXOLONE 39 HMDB0000017 4-pyridoxic acid 40 HMDB0000020 p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid 41 HMDB0000022 3-METHOXYTYRAMINE 42 HMDB0000026 ureidopropionic acid 43 HMDB0000030 BIOTIN 44 HMDB0000033 CARNOSINE 45 HMDB0000034 ADENINE 46 HMDB0000036 Taurocholic acid (TCA) 47 HMDB0000038 DIHYDROBIOPTERIN 48 HMDB0000043 BETAINE 49 HMDB0000045 ADENOSINE MONOPHOSPHATE (AMP) Inselspital Printed on 30.05.2018 University Institute of Clinical Chemistry Page 1/9 Bern, -

Supplemental Data

Article Detecting early myocardial ischemia in rat heart by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry ALJAKNA KHAN, Aleksandra, et al. Abstract Diagnostics of myocardial infarction in human post-mortem hearts can be achieved only if ischemia persisted for at least 6-12 h when certain morphological changes appear in myocardium. The initial 4 h of ischemia is difficult to diagnose due to lack of a standardized method. Developing a panel of molecular tissue markers is a promising approach and can be accelerated by characterization of molecular changes. This study is the first untargeted metabolomic profiling of ischemic myocardium during the initial 4 h directly from tissue section. Ischemic hearts from an ex-vivo Langendorff model were analysed using matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI IMS) at 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h. Region-specific molecular changes were identified even in absence of evident histological lesions and were segregated by unsupervised cluster analysis. Significantly differentially expressed features were detected by multivariate analysis starting at 15 min while their number increased with prolonged ischemia. The biggest significant increase at 15 min was observed for m/z 682.1294 (likely [...] Reference ALJAKNA KHAN, Aleksandra, et al. Detecting early myocardial ischemia in rat heart by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. Scientific Reports, 2021, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 5135 DOI : 10.1038/s41598-021-84523-z PMID : 33664384 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:150558 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Detecting Early Myocardial Ischemia in Rat Heart by MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry Online Supplementary Material for Scientific Reports Aleksandra Aljakna Khan1, Nasim Bararpour2,3, Marie Gorka4, Timothée Joye2,3, Sandrine Morel5, Christophe Montessuit5, Silke Grabherr1,2, Tony Fracasso1, Marc Augsburger1,2, Brenda R. -

Separation of Nucleic Acid Constituents Nucleic Acids Do Exist in Nuclei and Protoplasm of Biological Cells and Control the Growth and Heredity

Separation of Nucleic acid constituents Nucleic acids do exist in nuclei and protoplasm of biological cells and control the growth and heredity. There are two kinds of nucleic acids; DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid). There are six kinds of nucleotides formed of sugar, phosphoric acid and purine base or pyrimidine base, and four kinds of such nucleotides bond each other in various orders and constitute large molecules; poly-nucleotides or nucleic acids. Fig.VIII-7-1 illustrates such bond-structures of DNA and RNA and six kinds of bases that constitute them. Whereas DNA consists of four kinds of deoxy nucleotides the sugar component of that is 2-deoxy-D-ribose, deoxyadenylic acid (d-AMP), deoxyguanylic acid (d-GMP), deoxycytidylic acid (d-CMP) and deoxythymidylic acid (d-TMP), RNA consists of four kinds of ribo-nucleotides the sugar component of that is D-ribose, adenylic acid (AMP), guanylic acid (GMP), cytidylic acid (CMP) and uridylic acid (UMP). Another difference between DNA and RNA is that RNA holds uracil (Ura) instead of thymine (Thy) as pyrimidine base. DNA: Most of the bases are Ade, Gua, Cyt, Thy RNA: Bases are Ade, Gua, Cyt, Ura [Fig.VIII-7-1] Structures of nucleic acids Nucleic acids are used as written below: Firstly, taste nucleotides that are produced by enzymatic hydrolysis of RNA extracted from yeasts with NaCl or NaOH solutions are used as nucleic seasonings. Secondly, nucleotides are used as pharmaceuticals, e.g. anticancer agents, antiviral agents, blood circulation insufficiency and erebrovascular disease therapeutic agents. Yeast RNA produces, with yeast 5’-phosphodiesterase produced by Penicillium citrinum or Streptmyces aures, 5'-adenylic acid (5'-AMP), 5'-guanylic acid (5'-GMP), 5'-cytidylic acid (5'-CMP) and 5'-uridylic acid (5'-UMP), and 5'-AMP is then converted into 5'-inosinic acid (5'-IMP). -

The Novel Glutamine Antagonist Prodrug JHU395 Has Antitumor Activity in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Kathryn M

Published OnlineFirst October 8, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0319 MOLECULAR CANCER THERAPEUTICS | SMALL MOLECULE THERAPEUTICS The Novel Glutamine Antagonist Prodrug JHU395 Has Antitumor Activity in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Kathryn M. Lemberg1,2, Liang Zhao1, Ying Wu2, Vijayabhaskar Veeravalli2,3, Jesse Alt2, Joanna Marie H. Aguilar2, Ranjeet P. Dash2,3, Jenny Lam2, Lukas Tenora4, Chabely Rodriguez2, Michael T. Nedelcovych2,3, Cory Brayton5, Pavel Majer4, Jaishri O. Blakeley1,3, Rana Rais2,3, and Barbara S. Slusher1,2,3,6 ABSTRACT ◥ The carbon and nitrogen components of glutamine are used for peripheral nerve, were selectively susceptible to both glutamine multiple biosynthetic processes by tumors. Glutamine metabolism deprivation and GA dose-dependent growth inhibition. In vivo, and the therapeutic potential of glutamine antagonists (GA), how- orally administered JHU395 delivered active GA to tumors with ever, are incompletely understood in malignant peripheral nerve over 2-fold higher tumor-to-plasma exposure, and significantly sheath tumor (MPNST), an aggressive soft tissue sarcoma observed inhibited tumor growth in a murine flank MPNST model without in patients with neurofibromatosis type I. We investigated gluta- observed toxicity. Global metabolomics studies and stable isotope– mine dependence of MPNST using JHU395, a novel orally bio- labeled flux analyses in tumors identified multiple glutamine- available GA prodrug designed to circulate inert in plasma, but dependent metabolites affected, including prominent effects on permeate and release active GA within target tissues. Human purine synthesis. These data demonstrate that glutamine antago- MPNST cells, compared with Schwann cells derived from healthy nism is a potential antitumor strategy for MPNST. Introduction caused by germline loss of one copy of the RAS-GAP NF1 and presents with a wide range of manifestations including multiple cancers (12). -

769.Full.Pdf

Searches for Exploitable Biochemical Differences between Normal and Cancer Cells IX. Anabolism and Catabolism of Purines by Hepatomas 5123 and H-35* GLYNNP. WHEELER,Jo ANN ALEXANDER,ANNS. DODSON, SUSAND. BRIGGS,ANDHAROLDP. MORRIS (Kettering-Meyer Laboratory,^ Southern Research Institute, Birmingham, Alabama; and Laboratory of Biochemistry, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland SUMMARY The extents of anabolism and catabolism in vitro of purines and purine ribonucleo- tides by rat tissues, Morris Hepatoma 5123, and Reuber H-35 hepatoma were deter mined. The results are compared with those obtained previously for Novikoff hepato ma. Hepatoma 5123 was more active catabolically than any of the host tissues exam ined, including liver; H-35 tumor was about one-half as active catabolically as the host liver; and Novikoff hepatoma was much less active catabolically than the host liver. The results show that, although a deficiency of purine catabolism may be a contribut ing factor to the uncontrolled growth of some neoplasms, deficiency of purine catab olism is not a requisite for neoplastic growth. Previous studies (17) showed that more anab 6) were very similar to those of the host liver, it olism and less catabolism of radioactive purines seemed worth while to compare the extent of occurred with minces of several neoplasms (Leu catabolism of purines and purine ribonucleotides kemia L1210, Leukemia L4946, Leukemia L5178, by Hepatoma 5123 with that of the liver and Sarcoma 180, Adenocarcinoma 755, Human Sar other tissues of the host. Also, since studies of coma No. 1, Novikoff hepatoma) than with minces carbohydrate metabolism (13,15) of deoxycytidyl- of several tissues of the hosts. -

S41467-020-16810-8.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16810-8 OPEN Using arterial–venous analysis to characterize cancer metabolic consumption in patients ✉ Nanxiang Xiong 1,9,10 , Xiaofei Gao2,9, Hongyang Zhao1, Feng Cai2, Fang-cheng Zhang1, Ye Yuan1, Weichao Liu1, Fangping He 3, Lauren G. Zacharias2, Hong Lin1, Hieu S. Vu2, Chao Xing 4, Dong-Xiao Yao1, ✉ Fei Chen2, Benyan Luo4, Wenzhi Sun5,6, Ralph J. DeBerardinis 2,7, Hao Xu1 & Woo-ping Ge 5,8,10 Understanding tumor metabolism holds the promise of new insights into cancer biology, 1234567890():,; diagnosis and treatment. To assess human cancer metabolism, here we report a method to collect intra-operative samples of blood from an artery directly upstream and a vein directly downstream of a brain tumor, as well as samples from dorsal pedal veins of the same patients. After performing targeted metabolomic analysis, we characterize the metabolites consumed and produced by gliomas in vivo by comparing the arterial supply and venous drainage. N-acetylornithine, D-glucose, putrescine, and L-acetylcarnitine are consumed in relatively large amounts by gliomas. Conversely, L-glutamine, agmatine, and uridine 5-monophosphate are produced in relatively large amounts by gliomas. Further we verify that D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG) is high in venous plasma from patients with isocitrate dehydrogenases1 (IDH1) mutations. Through these paired comparisons, we can exclude the interpatient variation that is present in plasma samples usually taken from the cubital vein. 1 Department of Neurosurgery, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 430022 Wuhan, China. 2 Children’s Research Institute, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA. -

Supplemental Information Table S1, Related to Figure 1. Summary Characteristics of the Leigh Syndrome Patient Derived Fibroblast

Supplemental Information Table S1, Related to Figure 1. Summary characteristics of the Leigh syndrome patient derived fibroblast cell lines including the patient phenotype at diagnosis, the mutations identified, and published literature using the cell line. Table S2, Related to Figure 4. Day 10 LS derived neutralized embryoid bodies relative metabolite abundance for metabolites used in pathway analysis. LC-MS measured metabolite peak areas were normalized to the total ion count (TIC) by sample and fold change was determined by dividing each LS TIC normalized peak area by the control TIC normalized peak area for each metabolite. Metabolites were identified and filtered for pathway analysis using a threshold fold change (FC >5 and <0.4). Fold change values shown are averages for 2 independent runs with ~150 neuralized EBs per run. Table S3, Related to Figure 4. Summary of the metabolic pathways analysis for metabolites enriched in day 10 LS derived neuralized embryoid bodies. Statistical p values from enrichment analysis are adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. Total: total number of compounds in the pathway. Hits: matched number from the uploaded data. Raw p: original p value calculated from the enrichment analysis. Holm p: p value adjusted by Holm-Bonferroni method. FDR p: adjusted p value using False Discovery Rate. Impact: pathway impact value calculated from pathway topology analysis. Figure S1, Related to Figure 2. Characterization of Leigh syndrome iPSCs. A. Schematic representation of the fibroblast reprogramming protocol. B-C. Pluripotency characterization of the LS iPSCs. Samples were analyzed against samples in a reference data set (The International Stem Cell Initiative, 2018) (B).