IV.—Influence of Earth Movements on the Geological Strucuture Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knowing Our Communties 2017.Pdf

1 Contents District map .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 Summary of key points .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Five year plan .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Population ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Building stronger and healthier communities Health ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Life expectancy ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Obesity ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

NAAONB Annual General Meeting Business Meeting Agenda Thursday 19Th November 2020 10.30-11.30 A.M

NAAONB Annual General Meeting Business Meeting Agenda Thursday 19th November 2020 10.30-11.30 a.m. Meeting to be held by videoconference 01584 892112 (Clare Elbourne) Item 1 Apologies Item 2 Introduction of current NAAONB Board members (verbal) for information Item 3 AGM November 28th, 2019 - Minutes and matters arising for agreement Item 4 Art in the Landscape National Strategy (Kate Wood, Activate) for information Item 5 Chairman’s Annual Report 2019-20 for information. Item 6 Financial Report 2019-20 for agreement Item 7 CEO’s Report of work completed for NAAONB Business Plan Oct 2019 - Oct 2020 for information. Item 8 Review of Memorandum and Articles of Association for agreement Item 9 Membership Rates for Individual Lifetime Membership for agreement Item 10 Election of Trustees and appointment of auditors for agreement Item 11 AOB The National Association for Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Belmont House, Shrewsbury Business Park Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6LG 01584 892112 [email protected] Twitter @NAAONB A company limited by guarantee no: 4729800 1 Charity Number: 1158871 Registered office as above Item 3 - AGM November 28th 2019 - Minutes and matters arising Report to The Annual General Meeting of the National Association for AONBs Subject AGM November 28th 2019 - Minutes and matters arising Date 19th November 2020 Purpose For agreement MINUTES OF THE NAAONB ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 Thursday 28th November 2019 3.15 - 5.00pm Broadway House, Tothill Street, London, SW1H 9NQ Attendees Blackdown Hills -

Management Plan 2019-2024

Introduction Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019-2024 Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019-2024 1 Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019-2024 Malvern Hills AONB Management Plan (2019-2024) Introduction BIRMINGHAM OXFORD CARDIFF BRISTOL The Malvern Hills AONB © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Worcestershire County Council 100015914. For reference purposes only. No further copies may be made. Location of the Malvern Hills AONB 2 Contents Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019-2024 Contents Ministerial Foreword . 4 Chair’s Foreword .. 5 Section 1: Introduction . 6 About Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty . 6 The Malvern Hills AONB . 8 About the Management Plan . 12 Monitoring . 18 Section 2: The Natural and Cultural Environment . 20 Chapter 1: Landscape . 25 Chapter 2: Geodiversity . 30 Chapter 3: Biodiversity . 34 Chapter 4: Historic Environment . 42 Chapter 5: Farming and Forestry . 46 Section 3: Community Life . 56 Chapter 6: Living and Working .. 58 Chapter 7: Built Development . 64 Chapter 8: Tourism . 74 Chapter 9: Transport and Accessibility. 78 Section 4: Enjoying and Understanding . 84 Chapter 10: Recreation and Access . 86 Chapter 11: Information and Interpretation . 92 Chapter 12: Volunteering . 96 Glossary . 99 3 Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019-2024 Ministerial Foreword I am fortunate that England’s Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty are part of my Ministerial responsibilities . Whether it be rolling hills, sweeping coastline or a tranquil village, spending time in an AONB can stir the heart and lift the spirit . Ministerial Foreword Ministerial This is a pivotal moment for all AONBs . -

{Download PDF} the Cotswold Way Ebook Free Download

THE COTSWOLD WAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kev Reynolds | 240 pages | 30 Jun 2016 | Cicerone Press | 9781852848163 | English | Cumbria, United Kingdom The Cotswold Way PDF Book Cotswold Way North - Escarpment and Villages. We hope this website has helped bring you closer to the National Trails. Your organisation was great. Trail Information Find useful facts and learn more about the Cotswold Way below. So, whether you are a novice walker or an experienced hiker, we have the tour to suit you. A visit to Court Barn brings to life the talented designers and craftspeople who have worked in Chipping Campden and the north Cotswolds since the beginning of the twentieth century. In this email, you will be asked to confirm your tour details. Peter S. Are the prices for this place or activity budget-friendly? Accommodations were all really nice and people who ran them really friendly. This was the best walk of my life; enjoyed each of the towns on the Cotswold Walk. The maps and guidebook were excellent. Thank you for a wonderful and memorable week. Thank you for all of the work that you did in giving us a most memorable trip. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Wander between the grandeur of Victorian mills alongside the sleepy beauty of the waterway, and discover a timeless journey between past and present that reveals yet another face of the glorious Cotswolds. The itinerary of miles in 8 days tested us but we made it and there was a real sense of achievement when we reached Bath. -

Katy Magnall Development Management & Strategic Sites Ashford Borough Council Sent by Email To: Planning.Comments@Ashford

Katy Magnall Kent Downs AONB Unit Development Management & Strategic Sites West Barn Ashford Borough Council Penstock Hall Farm Canterbury Road East Brabourne Sent by email to: Ashford, Kent TN25 5LL [email protected] Tel: 01303 815170 Fax: 01303 815179 [email protected] www.kentdowns.org.uk 6 November 2019 Anglesey Arnside and Silverdale Blackdown Hills Cannock Chase Chichester Harbour Chilterns Clwydian Range Dear Katy Cornwall Cotswolds Application: 19/01327/AS: Wye College land and buildings Site Wye Gower 3, Olantigh Road, Wye. Cranbourne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Residential development of 40 dwellings with associated access road, Dedham Vale car park and open space. Dorset East Devon Thank you for consulting the AONB Unit on the above application. The Forest of Bowland following comments are from the Kent Downs AONB Unit and as such are at Howardian Hills an officer level and do not necessarily represent the comments of the whole High Weald AONB partnership. The legal context of our response and list of AONB Isle of Wight guidance is set out as Appendix 1 below. Isles of Scilly Kent Downs The site is allocated for housing in Wye’s Neighbourhood Plan and accordingly Lincolnshire Wolds the AONB Unit has no objection to the principle of the re-development of this Llyn site. Malvern Hills Mendip Hills Notwithstanding the brownfield nature of the site, we consider it Nidderdale disappointing that the applicant has requested that the Council apply the Norfolk Coast vacant buildings credit and propose a reduced provision of affordable housing North Devon within the scheme. -

The Complex Tectonic Evolution of the Malvern Region: Crustal Accretion Followed by Multiple Extensional and Compressional Reactivation

The complex tectonic evolution of the Malvern region: crustal accretion followed by multiple extensional and compressional reactivation Tim Pharaoh British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG ([email protected]) Abstract, The Malvern Hills include some of the oldest rocks in southern Britain, dated by U-Pb zircon analysis to c. 680Ma. They reflect calc-alkaline arc magmatic activity along a margin of the Rodinia palaeocontinent, hints of which are provided by inherited zircon grains as old as 1600Ma. Metamorphic recrystallisation under upper greenschist/amphibolite facies conditions occurred from c. 650–600Ma. Subsequently, rifting of the magmatic arc (c.f. the modern western Pacific) at c. 565Ma led to the formation of a small oceanic marginal basin, evidenced by basaltic pillow lavas and tuffs of the Warren House Formation, and Kempsey Formation equivalents beneath the Worcester Graben. By early Cambrian time this juvenile crust had stabilised sufficiently for thick quartz arenite-dominated sequences to accumulate, followed by mudstones in mid- to late-Cambrian time. In earliest Ordovician time, subsidence accelerated in a rift basin east of the Malverns, but was terminated by accretion of the Monian Composite Terrane to the Gondwana margin. Rifting led to a microcontinental flake (‘East Avalonia’) breaking away, eventually to impact with Laurentian terranes on the other margin of the Iapetus Ocean in early Silurian time. Minor inversion of the floor of the Worcester Graben might have occurred during the Acadian (early Devonian) deformation phase, but more significantly, during the Variscan (end Carboniferous) Orogeny, when a ‘Rocky Mountain Front’-type uplift was generated opposite a pinch-point within the orogen. -

Great Malvern Circular Or from Colwall)

The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular) The Malvern Hills (Colwall to Great Malvern) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 20th July 2019 21st July 2019 Current status Document last updated Monday, 22nd July 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular or from Colwall) Start: Great Malvern Station or Colwall Station Finish: Great Malvern Station Great Malvern station, map reference SO 783 457, is 11 km south west of Worcester, 165 km north west of Charing Cross, 84m above sea level and in Worcestershire. Colwall station, map reference SO 756 424, is 4 km south west of Great Malvern, 25 km east of Hereford, 129m above sea level and in Herefordshire. -

103. Malvern Hills Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 103. Malvern Hills Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 103. Malvern Hills Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we North are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are East areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good Yorkshire decision-making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Pdf Economic Development Strategy

MALVERN HILLS district 2013/18 Economic Development Strategy Open to Innovation Malvern Hills District Council www.malvernhills.gov.uk Malvern Hills District Economic Development Strategy 2013 - 2018 Open to Innovation Our approach to translating ideas, both big and small, into commercial success Policies and support aimed at economic prosperity across the District will be driven by developing an understanding of the needs of our economy, community and what makes this area both special and different. We will seek to maximise the linkages between business sectors and suppliers within the district and further afield. Our aim will be ensure the economic success of the district by delivering a balanced economy providing a broad range of employment in both established and new types of employment. We will relate employment opportunities to the needs of the wider community. For example our policies for sustainable economic growth will need to recognise that our existing workforce will be working longer but it is aging. Therefore we need to attract and retain a younger workforce whilst expanding opportunities for the changing employment needs of people approaching 70 to ensure access to a suitably skilled local workforce is not going to become a constraint to future growth and investment, and encourage greater commuting. We will also have to address the implications of an aging population in terms of the services required to support its needs associated. We believe a successful district that understands its strengths and what makes it distinctive can realistically promote economic development across a wide range of sectors from cyber security to agriculture – rather than putting all of its eggs in one virtual basket. -

Age UK Worcester & Malvern Hills

Age UK Worcester & Malvern Hills Spring 2021 Newsletter 2 Contents 3. Feature 13. Service updates 4. Covid-19 update 14. Get involved 5. Latest news 15. Contacts 6. Latest news 7. Feature 8. Shopping with us 9. Donations 10. Volunteer with us 11. Positive stories 12. Service list Registered Charity No: 1114859. Registered Company: 5688674. @ageukwmh 3 Feature These handy infographics show the Roadmap from the Government for our recovery from Coronavirus. These are just guides and may change over time. @ageukwmh Registered Charity No: 1114859. Registered Company: 5688674. 4 Covid-19 update Following the updated Government Guidance regarding Coronavirus and have taken the following decisions in order to comply with the guidance and to help keep members of our community safe. • Our collection service is now active across Worcester and Malvern Hills. Our van drivers can collect your donations COVID-19 safe, directly from your door. At this time you may submit a collection request, via the online form, or by calling our offices, and we will put you onto our waiting list. • All 7 of our Charity Shops are now open, in line with the next phase of the Governments Coronavirus roadmap. If you are visiting one of our stores, please be aware that social distancing measures, sanitising and limited capacity will be in operation for the foreseeable future. This is to ensure that our staff and customers stay as safe as possible when shopping with us. • Our eBay For Charity Shop continues to operate, however please expect longer dispatch times, as we are running with limited staff. -

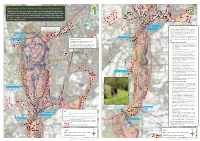

Map-And-Guide-Website-Page-1.Pdf

Welcome to the Malvern Hills and Commons The Malvern Hills and surrounding commons can be explored by the network of footpaths and bridleways that criss-cross this iconic landscape. With unique geology, ancient archaeology, interesting wildlife and spectacular views, use 1 2 this map to help you find your way around the peaks of the Malvern Hills and the wide, open commons. Earnslaw car park A series of waymarked cycling trails Access in a shared landscape Beacon Road car park begin from North Quarry car park. The Malvern Hills and Commons are a shared landscape www.malvernhills.org.uk/visiting/cycling for everyone to enjoy. Hundreds of thousands of visitors come each year to walk, cycle, even hang glide. The Hills Tank Quarry car park are also a working landscape and livestock continue to graze here, cared for by graziers. We work hard to take care of the Hills and Commons for Jubilee Drive car park local people, visitors, local graziers and wildlife. Please help North Quarry car park Arriving by train us to look after this special place by following these simple tips. The Malvern Hills can easily be reached from either Great Malvern or Malvern Link train station. Walking on the Malvern Hills From Great Malvern station, follow a trail designed by • Walkers have a right of access over land under our Route to the Hills which will guide you all the way to the care but we ask you to stick to the main walking paths foot of the Malverns. www.routetothehills.co.uk where possible to avoid disturbance to wildlife and grazing livestock • Please take your litter home with you • Please keep your dog under close control at all times • Take extra care when near livestock. -

THE COTSWOLDS Malvern Hills Pershore Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Evesham

Worcester MORGAN HIRE CAR ROUTE A449 A THE COTSWOLDS Malvern Hills Pershore Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Evesham Upton-Upon The Cotswolds covers a huge area, almost 800 square miles, Severn and runs through five counties (Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, Wiltshire and Worcestershire). One of the delights of visiting the Cotswolds is exploring the different areas, each with Broadway its own identity, yet all with those defining Cotswold features: M50 golden stone and rolling hills, the ‘wolds’. Beautiful driving roads A46 Snowshill make this stunning part of the country ideal for a top down Tewksbury #MorganAdventure. We’d loosely recommend a loop that sticks to A and B roads M5 taking in Upton-Upon-Severn, Pershore, Broadway, Snowshill, The Slaughters, Northleach, Burford and then back through Stow-On-The-Wold and Tewkesbury. The joy of the Cotswolds is Stow-on-the-Wold Town Council turning off the beaten track, exploring the quintessentially English Upper Slaughter villages of honey coloured stone, enjoying the stunning scenery Cheltenham from the cockpit of a Morgan. A424 Bourton-on-the-Water A429 POINTS OF INTEREST: Northleach A40 • Snowshill Manor and Garden - National Trust, WR12 7JU • Broadway Tower - Cotswolds Highest Tower, WR12 7LD Burford • Royal Oak, Ramsden - Good Pub Guide recommended, and an ideal lunch stop OX7 3AU M5 • Stow on The Wold - Quintessential Cotswold Town • Burford - Historic Market Town The Cotswolds An Area of Outstanding • The Slaughters - Twin villages situated near to Natural Beauty Bourton-On-The-Water • The Swan Hotel, Bibury - A former Cotswold coaching inn and an ideal lunch stop, GL7 5NW From: Malvern WR14 2LL Via: Stow-on-the-Wold & Bourton-on-the-Water To: Shipton-Under-Wychwood (and return) Distance: 103 miles Time: 2hr 56min.