Gujarat: the Transition to a West Indian Tiger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOK SABHA DEBATES /~Nglish Version)

eries, Vol. XXXII, No.1 ~onday,June13,1994 Jyaistha 23,1916 (Saka) ~ /J7r .t:... /jt.. LOK SABHA DEBATES /~nglish Version) Tenth Session (Tenth Lok Sabha) PARLIAMENT LiBRARY No................... ~, 3 ......~' -- l)ate ... _ -~.. :.g.~ ~ ..... - (Vol. XXXIJ contains No. I to 2) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: Rs., 50,00 [ORIGINAL ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGLISH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE TREATED AS AUTHORITATIVE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF.) \.J1 (') ".... r--. 0'\ 0 .... ..... t- -.1 ::s ct ..... ....... ct" "- ~ ~ CD ~ \.0 _. ..... ::s ..... vJ e;- O' ~ ::s en Po I-cJ i ..~ &CD ~ p ~ ~ m .... c.; Cl to tp ~ p; ::r t- Il' .. r-- rt c.". ..... b' t: t=~ I'i' t- ~ Ll> .... ~ ti t- \.0 ::s t<: ~ \.0 ~ su ~ .. ~ cr. 0 ~ ..... ~ 0 .. ~ Ci; ~ )--'. 0' Ii (i..i :::T I~ CD ::r Ii ;::F '1 'Ii ~ :::T jl) cT ,-. 11 ~ tJ· I ~ 0 ()q ,.... ~ t. (I) !i. .... .- c: eD ::s (1) 112 w r) .... fl) Z ..., .1- Ql ~ -~ ..... tJ' .~ . Q ~ ~ 0 ~ 0 III SU . g;. I\) ::s '-' p:> g ~ Ii I';" .. g _" ~ 1.0.... 0'\ ,...... (l)C04 CI b:I ttl (/2 PlSl'l ::r .... PI ~ :::r c.". I-' ~ tS' ~~ .g jl) .... ~ ....,~ ::S~ .., tel ~ ~! ~ ~ SU ::s U; ~(I) .. ::r (j) Ii &~ ::r t- ti .... f-Io :?: § .~ ,.... ~ CQ . ::r ~ ::s ;S; ~ ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERRS TENTH LOK SABHA A Ayub Khan, Shri (Jhunjhunu) Abdul Ghafoor, Shr; (Gopalganj) Azam, Dr. Faiyazul (Bettiah) oedya Nath, Mahant (Gorakhpur) B Ar"aria, Shri Basudeb (Bankura) Baitha, Shri Mahendra (Bagaha) Adaikalaraj, Shri L. (TiruchirapaUi) Bala, Dr. Asim (Nabadwip) Advani, Shri Lal K. -

Role of Media in Promoting Communal Harmony (2012)

Role of Media in Promoting Communal Harmony National Foundation for Communal Harmony New Delhi 2012 Published by: National Foundation for Communal Harmony (NFCH) 9th Floor, ‘C’ Wing, Lok Nayak Bhawan Khan Market, New Delhi-110 003 © 2012, National Foundation for Communal Harmony (NFCH) ‘Any part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means with due acknowledgement to NFCH’ ISBN- 978-81-887772-11-7 Role of Media in Promoting Communal Harmony 2 Role of Media in Promoting Communal Harmony Sl. Contributors Title Page No. No. 1. Radhakrishnan B Media - the fourth pillar of the society 1-7 2. Aishvarya Singh Media gets great power alongwith great 8-17 responsibility 3. Rajan Vishal Media has a responsible role in 18-24 strengthening communal harmony 4. Ashwini Sattaru Security of all is in a free press 25-34 5. Harsh Mangla Media has to be sensitive for harmony 35-42 6. Mariam F. Sadhiq Media is a double edged sword 43-46 7. Lalithalakshmi The press is the best instrument for 47-54 Venkataramani enlightening the minds of men 8. Karma Dorji Media must help society to define and 55-59 promote right values 9. Rahul Jain Media can steer the country in a direction 60-65 where peace prevails 10. Dhavalkumar Content of the Media should be 66-72 Kirtikumar Patel congenial for Harmony 11. Adesh Anand Media can play harmonizing role in the 73-81 Titarmare society 12. Shemushi Bajpai Media is the key for building Communal 82-86 Harmony 13. Hkjr ;kno ehfM;k& yksdra= dk izgjh 87-92 14. -

Citizens Or Justice and Peace

FH)<'. IiU,: Apr. 21 2E111 11 :111,,iikm Citizens or Justice and Peace April 21, 2011 To, Shri AK Malhotra Special Investigation Team (SIT) Gandhinagar 't ktIre d\r? I Reference: 161 Statement SL • 1088 2008 Dear Shri Malhotra, Pursuant to the recording of my 161 statement in the SLP 1088/2008 following the directives of the Hon'ble Supreme Court on 15.3,2011, the SIT had recorded my statement which was an unsigned statement in Mumbai at my residence on Monday, 11.4. 2011. There are certain points that I wish to place on record following this aspects to be considered as part of the 161 statement. I urge that this letter is read with my 161. statement or attached to it as have been the detailed materials placed by us before the Hon'ble Supreme Court on 10.8.2010. I. As has been pointed out in point 15 in the attached NOTE annexed herein --- that I had handed over to you on 11,4.2011 -- the highest criminal culpability of the higher echelons of the Gujarat especially Ahmedabad Police/Political Class relates to the destruction of vital records related to the 2002 violence. This destruction appears to have found mention in your report submitted to the Hon'ble Supreme Court on 14.5.2010 as revealed by subsequent developments and has thereafter also led to applications and legal moves to get criminally prosecuted whosoever may be responsible for this destruction. (Possibilities are that the higher level of police officials, IAS officials in the Home Department as maybe also the chief executive of the state who is also himself Home Minister, may have a role in this methodical destruction). -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

“BSE's Iconic Tower to Come up at GIFT City in Gujarat”

MEDIA COVERAGE On “BSE’s iconic Tower to come up at GIFT City in Gujarat” PUBLICATION NAME : Financial Express EDITION : All Editions DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 16 PUBLICATION NAME : Business Standard EDITION : Ahmedabad and Pune DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 04 PUBLICATION NAME : The Hindu Business Line EDITION : Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Hyderabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 15 PUBLICATION NAME : The Economic Times EDITION : All Editions DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 03 PUBLICATION NAME : The Times of India EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 01 PUBLICATION NAME : DNA EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 01 PUBLICATION NAME : The Indian Express EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 04 PUBLICATION NAME : The Pioneer EDITION : All Editions DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 07-10 PUBLICATION NAME : Deccan Chronicle EDITION : Bangalore, Chennai and Kochi DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 12 PUBLICATION NAME : The Asian Age EDITION : Mumbai, Delhi and Kolkata DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 15 PUBLICATION NAME : Gujarat Samachar EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 02 PUBLICATION NAME : Divya Bhaskar EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 04 PUBLICATION NAME : NavGujarat Samay EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 12 PUBLICATION NAME : Sandesh EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 02 PUBLICATION NAME : The Economic Times (Gujarati) EDITION : Ahmedabad and Mumbai DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 02 PUBLICATION NAME : The Financial Express (Gujarati) EDITION : Ahmedabad DATE : 16-10-2014 PAGE : 04 PUBLICATION NAME : Jansatta EDITION : Ahmedabad -

Manav Utthan (E).Pmd

have not stopped till to-day. In fact, the whole world today is in search of a great revolution. The people of many countries, today, blew the bugles of revolution. It started from Tunisia with a small matter. A man, earning his bread from a business of selling vegetables was standing aside the road along with his vegetable cart. At that time a police inverted his cart, perhaps he could not have paid him his instolements. It was a question of life and death for that poor man. He was confounded and he burnt himself on the spot. In fact the 90% people of Tunisia lived in such a burning like condition. The flame of the poor man spreaded all over Tunisia and within couple of minutes the crowds of people all over the country got together flying the flags of peaceful revolution and the king had to run away. Inspired from this, a young man and a woman put on a message of revolution like Tunisia, on internet and on the next Please make revolution only after thoughtful day lacs of people of Egypt gathered on the road with the flags planning, so that the purpose may serve of revolution. Then, this situation took place in many countries Revolution ! Revolution ! Revolution ! Since the selfish and of 22 Arabian countries. This happened in many countries of Africa. Developed countries like China, Italy, Russia did not cruel king was born in the world, either leader or the public had hoisted the flag of revolution against him. The main reason was remain untouched by their people's upsurge. -

6 What Happened in Gujarat

WHAT HAPPENED IN GUJARAT? THE FACTS The following narrative draws from various sources: newspaper reports, fact-finding missions and other reports which came out after the Gujarat carnage. It pieces together the sequence of events that occurred in and around Godhra before, on and after 27th February 2002 (the incident that allegedly sparked off the ensuing communal violence in the State of Gujarat), and details of the extent and nature of the terrible violence against Muslims in Gujarat in the months that followed. I. Setting The Context: Before 27 February 2002 History of Communal Tension in Godhra The town of Godhra in Gujarat has a long history of inter-community tensions stemming from the fact that in 1947, when India achieved independence and was partitioned to create Pakistan, thousands of Hindus fleeing Pakistan settled in Godhra, and vented their anger at Godhra’s Muslims, burning their homes and businesses with truckloads of gasoline. Since then, government officials have deemed the town one of the country’s most “communally sensitive” places in India. In the 1980’s and again in 1992, it was wracked by riots initiated by members of both communities. Today Godhra, a town of 15,000, is evenly split between Hindus and Muslims, most of whom live in segregated communities separated in places by train tracks. There is little interaction between them and both regard one another with suspicion. The Temple at Ayodhya: A Cause for Tension During the Kumbh Mela (an annual Hindu religious fair) in January 2001, the VHP (Vishva Hindu Parishad – World Hindu Council) ‘Dharma Sansad’ (Religious Council) decided that the construction of a Ram Temple on the site of the Babri Masjid (ancient mosque built on the site of a demolished temple, finally demolished by Hindu activists of the VHP and other right wing forces on 6 December 1992) would start on March 12 of 2002. -

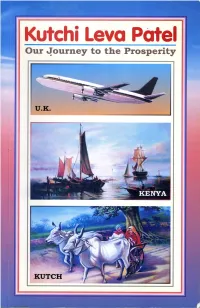

Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No

Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No. Author Shree S. P. Gorasia 1 Cutch Social & Cultural Society 10 First Published on: 2 Leva Patel Migration 14 Vikram Samvat – 2060 Ashadh Sood – 2nd (Ashadhi Beej) 3 Present Times 33 Date: 20th June 2004 4 Village of Madhapar 37 Second Published on: Recollection of Community Service Vikram Samvat – 2063 Ashadh Sood – 1st 5 Present Generation 55 Date: 15th July 2007 6 Kurmi-Kanbi - History 64 (Translated on 17 December 2006) 7 Our Kutch 77 Publication by Cutch Social and Cultural Society 8 Brief history of Kutch 81 London 9 Shyamji Krishna Varma 84 Printed by Umiya Printers- Bhuj 10 Dinbandhu John Hubert Smith 88 Gujarati version of this booklet (Aapnu Sthalantar) was 11 About Kutch 90 published by Cutch Social & Cultural Society at Claremont High School, London, during Ashadhi Beej celebrations on 12 Leva Patel Villages : 20th June 2004 (Vikram Savant 2060) with a generous support from Shree Harish Karsan Hirani. Madhapar 95 Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No. Author Shree S. P. Gorasia 1 Cutch Social & Cultural Society 10 First Published on: 2 Leva Patel Migration 14 Vikram Samvat – 2060 Ashadh Sood – 2nd (Ashadhi Beej) 3 Present Times 33 Date: 20th June 2004 4 Village of Madhapar 37 Second Published on: Recollection of Community Service Vikram Samvat – 2063 Ashadh Sood – 1st 5 Present Generation 55 Date: 15th July 2007 6 Kurmi-Kanbi - History 64 (Translated on 17 December 2006) 7 Our Kutch 77 Publication by Cutch Social and Cultural Society 8 Brief history of Kutch 81 London 9 Shyamji Krishna Varma 84 Printed by Umiya Printers- Bhuj 10 Dinbandhu John Hubert Smith 88 Gujarati version of this booklet (Aapnu Sthalantar) was 11 About Kutch 90 published by Cutch Social & Cultural Society at Claremont High School, London, during Ashadhi Beej celebrations on 12 Leva Patel Villages : 20th June 2004 (Vikram Savant 2060) with a generous support from Shree Harish Karsan Hirani. -

When Justice Becomes the Victim the Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat

The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat When Justice Becomes the Victim The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat May 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School http://humanrightsclinic.law.stanford.edu/project/the-quest-for-justice International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School Cover photo: Tree of Life jali in the Sidi Saiyad Mosque in Ahmedabad, India (1573) Title quote: Indian Supreme Court Judgment (p.7) in the “Best Bakery” Case: (“When the investigating agency helps the accused, the witnesses are threatened to depose falsely and prosecutor acts in a manner as if he was defending the accused, and the Court was acting merely as an onlooker and there is no fair trial at all, justice becomes the victim.”) The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat When Justice Becomes the Victim: The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat May 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School http://humanrightsclinic.law.stanford.edu/project/the-quest-for-justice Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC AT STANFORD LAW SCHOOL, WHEN JUSTICE BECOMES THE VICTIM: THE QUEST FOR FOR JUSTICE AFTER THE 2002 VIOLENCE IN GUJARAT (2014). International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School © 2014 International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic, Mills Legal Clinic, Stanford Law School All rights reserved. Note: This report was authored by Stephan Sonnenberg, Clinical Supervising Attorney and Lecturer in Law with the International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic (IHRCRC). -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences SEWA in RELIEF

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences SEWA IN RELIEF: GENDERED GEOGRAPHIES OF DISASTER RELIEF IN GUJARAT, INDIA A Thesis in Geography and Women’s Studies by Anu Sabhlok © 2007 Anu Sabhlok Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 The thesis of Anu Sabhlok was reviewed and approved* by the following: Melissa W. Wright Associate Professor of Geography and Women’s Studies Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Lorraine Dowler Associate Professor of Geography and Women’s Studies James McCarthy Associate Professor of Geography Mrinalini Sinha Associate Professor of History and Women’s Studies Roger M. Downs Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ABSTRACT The discourse of seva – selfless service - works within the spaces of the family, community and the nation in India to produce gendered subjects that are particular to their geographic and historic location. This study is a geographic analysis of the discourse of seva as it materializes in the context of disaster relief work in the economically liberalizing and religiously fragmented state of Gujarat in India. I conducted ethnographic research in Ahmedabad, Gujarat during 2002-2005 and focused my inquiry on women from an organization whose name itself means service––SEWA, the Self-Employed Women’s Association. SEWA is the world’s largest trade union of informal sector workers and much has been written about SEWA’s union activity, trade and production cooperatives, legal battles, and micro-credit success stories. However, despite SEWA’s almost 30 years of active engagement in disaster relief, there is not a single text focusing on SEWA’s activism in terms of its relief work. -

Premeditated Causes of the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom: a Comprehensive Analysis of Contributing Factors That Led to the Manifestation of the Riots

Page 128 Oshkosh Scholar Premeditated Causes of the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom: A Comprehensive Analysis of Contributing Factors that Led to the Manifestation of the Riots Tracy Wilichowski, author Dr. James Frey, History, faculty adviser Tracy Wilichowski graduated from UW Oshkosh with the distinction of summa cum laude in May 2012. During her time at Oshkosh, she acquired history and philosophy degrees and minored in social justice. Throughout college, she was active in the Philosophy Club and was the director of Student Legal Services during her senior year. Her interest in South Asian communalism began after studying abroad for a semester in India. Tracy is teaching at a low-income school for the next two years through the Teach For America program and plans to pursue a Ph.D. in South Asian studies. Dr. James Frey is an assistant professor in the UW Oshkosh History Department, specializing in the history of India. He has taught courses on Islamic history and communalism in India, in addition to the Indian history surveys. He is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of California–Berkeley. His research interests include the history of Indian magic, the East India Trade, and the East India Company Raj. Abstract In the last 30 years, the nature of communalism in India has changed significantly. This increase in violence is commonly attributed to the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP); however, there are other factors that contributed to the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. Despite the considerable research done on the Gujarat riots, little is known about their cause, aside from the BJP’s apparent involvement. -

Total Coverage: 14 Print & 9 Online

INDEX: Total Coverage: 14 Print & 9 Online S. No. Publication Headline Date PRINT Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential 1. The Economic Times January 22, 2019 Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 2. Ahmedabad Express Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 3. Prabhat Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 4. Gujarat Today Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 5. Western Times Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 6. Gujarat Guardian Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 7. Gandhinagar Samachar Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 8. Standard Herald Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 9. Janmabhoomi Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 10. Karnavati Express Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 11. Savera India Times Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 12. Alpviram Rooftop Solution launched 13. Phulchhab Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 Rooftop Solution launched Headline: Tata Power Solar Residential January 22, 2019 14. Atal Savera, Navsari Rooftop Solution launched ONLINE Tata Power Solar Launches Residential 1. January 21, 2019 Business Standard Rooftop Solution In Gandhinagar Tata Power Solar Launches Residential 2. January 21, 2019 Electronics B2b Rooftop Solution In Gandhinagar Tata Power Solar Now Launches An Extensive 3. January 21, 2019 Energy Infra Post Rooftop Solution At Gandhinagar Tata Power Solar Now Launches An Extensive 4.