Sharing Responsibilities in Fisheries Management Part 2 - Annex: Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anleggskonsesjon

Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat N V E Anleggskonsesjon I medhold av energiloven - lov av 29. juni 1990 nr. 50 Meddelt: Statnett SF Organisasjonsnummer: 962986633 Dato: 07.06.2010 Varighet: 07.06.2050 Ref: NVE 200700954-175 og 200800700-192 Kommune: Overhalla, Namsos, Namdalseid, Osen, Roan og Åfjord Fylke: Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag Side 2 I medhold av lov 29.06.1990 nr. 50 (energiloven) og fullmakt gitt av Olje- og energidepartementet 14.12.2001, gir Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat under henvisning til søknader oversendt fra Statnett 13.11.07, 30.01.09, 03.06.09, 20.11.09 og vedlagt notat Bakgrunn for vedtak av 04.06.10 Statnett SF tillatelse til i Overhalla, Namsos, Namdalseid kommuner i Nord-Trøndelag og Osen, Roan og Åfjord kommuner i Sør-Trøndelag å bygge og drive følgende elektriske anlegg: En ny 120 km lang 420 kV kraftledning fra Namsos transformatorstasjon til Storheia transformatorstasjon via Roan transformatorstasjon. Kraftledningen skal i hovedsak bygges med Statnetts standard selvbærende portalmast i stål med innvendig bardunering og fargeløse glassisolatorer med V-kjedeoppheng. Det settes vilkår om annen materialbruk og farger for ca. 22 kilometer av kraftledningen, se under. Linene skal være av typen duplex parrot FeAl 481 i mattet utførelse, og det skal være to toppliner i stål, hvorav en med fiberoptisk kommunikasjonskabel. Kraftledningen skal bygges etter følgende trasi vist på vedlagte kart merket "Tilleggssøknad" (2 stk) datert 27.11.08 (vedlegg søknad 30.01.09), "Traskart, vedlegg konsesjonssøknad" datert 15.05.09 (Vedlegg søknader 03.06.09) og Figur 1 i tilleggssøknad av 20.11.09 : For strekningen mellom Namsos transformatorstasjon i Overhalla kommune og Roan transformatorstasjon i Roan kommune: 2.0-3.0-3.1-3.1.1-3.1-3.1.3-3.0-3.3-3.5 For strekningen mellom Roan transformatorstasjon i Roan kommune og Storheia transformatorstasjon i Afford kommune: 1.1-1.2.1-1.1-1.4. -

Flatanger, Namdalseid, Fosnes Og Namsos 1994.Pdf (3.142Mb)

00 M LD/ING A AN r ln A CIU, i\J Afv1 Haltenbanken o o l) l) i ..;' t FORORD Arsmeldingen fra fiskerirettlederen i .~latanger, Namdalseid, Fosnes og Namsos legges herved frem. ~-.· Meldinga beskriver sysselsetting og aktivitet i fiskeri- og havbruksnæringa i rettledningsdistriktet samt Indre Trondheimsfjord. Opplysningene er innhentet fra egne register, Fiskeridirektoratet, Norges Råfisklag, og fiskeri og oppdrettsbedrifter i distriktet. Lauvsnes 15.09.95 Anita Wiborg y.: f l. INNHOLDSFORTEGNELSE: l. O KORT OM DISTRIKTET. • • • • • • • • • • .. .. • • • • • • • .. • .. • • • • • • • • • • • 2 _,..;: 2. O SAMMENDRAG ...................... '... • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • .. 3 3 • O SYSSELSETTING. • • • • • • • • • .. • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 3 .l Fiskermanntallet ...................................... 5 3. 2 Mottak og foredling ................................... 7 3.3 Oppdrettsnæringa- matfisk/settefisk ................... ? 3.4 Slakting/pakking av oppdrettsfisk ...................... 8 3.5 Sammendrag- sysselsetting ......•.................... 9 4. O FISKEFLATEN ............................................ l O 4. l Merkeregisteret ......•............................... lO 4 . l A l der . ........... l O 4 • 3 Lengde ................................................... 11 4. 4 Sammendrag - merkeregisteret ......................... 12 4. 5 Konsesjoner .........................................• 12 4.6 Flåtens aktivitet borte og hjemme ..................... l3 5.0 MOTTAK- OG FOREDLINGSBEDRIFTENE -

Oktober 06.Pub

NYTT FRA NAMDALSEID KOMMUNE OKTOBER. 06 Elgjakta - ”høstens vakreste KOMMUNALE MØTER: eventyr” - for mange - er i • UNGDOMSRÅD 30.10. gang! • ELDRERÅD 31.10. • FORMANNSKAP 19.10. Utlegging: Forslag til reguleringsplan for Nord-Statland er lagt ut til offentlig ettersyn i perio- den 18.09.-18.10.06. Planen er utlagt på Biblio- tek/Servicekontor, Coop Namdalseid, Coop Sjøåsen, Nerbutikken AS og på kom- munens hjemmeside www.namdalseid.kommune. no Foto: Geir Modell I Nord-Trøndelag skal det i år felles 5913 dyr og 310 av disse skal falle i Namdalseid kommune. Det er mange jegere involvert når en så stor mengde kjøtt skal høstes, og for Namdalseid’s del er ca. 430 jegere, fordelt på 53 jaktfelt og 12 vald. Kjøttet av 310 elg tilsvarer ca. 37 tonn med en førstehåndsverdi på om lag 2,5 mill. kroner. NAMDALSEID KOMMUNE 7750 Namdalseid Melkrampa ønsker alle jegere ”skitt” jakt. Nytt nettsted for Miljø og landbruksforvaltningen Miljø og landbruksforvaltningen i MNR utvikler nå eget nettsted. Her finner du nyttig informasjon relatert til hele dette fagområdet. Tlf. 74 22 72 00 Adressen er: www.midtre-namdal.no/miljoland . Tips til videre utvikling Åpent 08.00-15.30 ønskes! Ordførerens spalte Godt rustet mot en mørkere årstid Etter en lang, fin og varm som- også blir positiv og god reklame for å oppleve en fantastisk na- mer, er naturen innrettet sånn at for Namdalseid Kommune. tur! vi nå går mot ei mørkere tid. Jeg vil for eksempel nevne Selv om vi går inn i en mørkere Men takket være denne fine ”Molomarkedet” på Statland, årstid, er det håp om at vi som sommeren er det også lettere å som har fått mye velfortjent po- kommune kan gå framtiden lyst gå vinteren i møte. -

Nye Fylkes- Og Kommunenummer - Trøndelag Fylke Stortinget Vedtok 8

Ifølge liste Deres ref Vår ref Dato 15/782-50 30.09.2016 Nye fylkes- og kommunenummer - Trøndelag fylke Stortinget vedtok 8. juni 2016 sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke fra 1. januar 2018. Vedtaket ble fattet ved behandling av Prop. 130 LS (2015-2016) om sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag fylker til Trøndelag fylke og endring i lov om forandring av rikets inddelingsnavn, jf. Innst. 360 S (2015-2016). Sammenslåing av fylker gjør det nødvendig å endre kommunenummer i det nye fylket, da de to første sifrene i et kommunenummer viser til fylke. Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB) har foreslått nytt fylkesnummer for Trøndelag og nye kommunenummer for kommunene i Trøndelag som følge av fylkessammenslåingen. SSB ble bedt om å legge opp til en trygg og fremtidsrettet organisering av fylkesnummer og kommunenummer, samt å se hen til det pågående arbeidet med å legge til rette for om lag ti regioner. I dag ble det i statsråd fastsatt forskrift om nærmere regler ved sammenslåing av Nord- Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet fastsetter samtidig at Trøndelag fylke får fylkesnummer 50. Det er tidligere vedtatt sammenslåing av Rissa og Leksvik kommuner til Indre Fosen fra 1. januar 2018. Departementet fastsetter i tråd med forslag fra SSB at Indre Fosen får kommunenummer 5054. For de øvrige kommunene i nye Trøndelag fastslår departementet, i tråd med forslaget fra SSB, følgende nye kommunenummer: Postadresse Kontoradresse Telefon* Kommunalavdelingen Saksbehandler Postboks 8112 Dep Akersg. 59 22 24 90 90 Stein Ove Pettersen NO-0032 Oslo Org no. -

Noen Rapporter Som Omhandler Geokjemi I Nord-Trøndelag Og Fosen

Postboks 3006 - Lade 7002 TRONDHEIM Tlf. 73 90 40 11 Telefaks 73 92 16 20 RAPPORT Rapport nr.: 96.212 ISSN 0800-3416 Gradering: Åpen Tittel: Oversikt over: Geologiske kart og rapporter for Namdalseid kommune Forfatter: Oppdragsgiver: Rolv Dahl Nord-Trøndelagsprogrammet Fylke: Kommune: Nord-Trøndelag Namdalseid Kartblad (M=1:250.000) Kartbladnr. og -navn (M=1:50.000) Namsos Forekomstens navn og koordinater: Sidetall: 24 Pris: Kartbilag: Feltarbeid utført: Rapportdato: Prosjektnr.: Ansvarlig: 10.02.97 2509.11 Sammendrag: "Det samlede geologiske undersøkelsesprogram for Nord-Trøndelag og Fosen" avsluttes i 1996. 10 år med geologiske undersøkelser har gitt en omfattende geologisk kunnskapsbase for Nord- Trøndelag og Fosen. Bruk av geologiske data kan ha store nytteverdier i kommunal sektor. Rapporten viser hvilke undersøkelser som er gjennomført både på fylkesnivå, regionalt og kommunalt i Namdalseid kommune, hvilken geologisk informasjon som foreligger og vil foreligge i nær fremtid, og mulig fremtidig bruk av denne informasjonen. I NGUs referansedatabaser er det til sammen registrert 28 ulike publikasjoner og kart som omhandler geologiske tema spesifikt i Namdalseid kommune. Av disse er 12 kart i M 1:50.000 med ulike geologiske tema. Foruten generell kartlegging av berggrunn og løsmasser, inkludert sand- og grusressurser, har mye av NGUs aktiviteter i kommunen vært knyttet til leting etter grunnvannsressurser og mineralressurser. Mulighetene for bruk av grunnvann til drikkevannsforsyning er rapportert. Et kalksteinsfelt ved Derråsbrenna er vurdert som råstoffkilde både til industrimineral (jordbrukskalk) og naturstein. Funn av hvalbein i løsmasser i Utvorda, ga viktige data og la grunnlaget for en populærvitenskapelig presentasjon av den kvartærgeologiske historien i området. En gjennomgang av datagrunnlaget på digital form gis i NGU- rapport nr. -

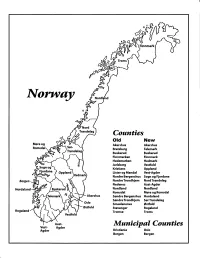

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Poststeder Nord-Trøndelag Listet Alfabetisk Med Henvisning Til Kommune

POSTSTEDER NORD-TRØNDELAG LISTET ALFABETISK MED HENVISNING TIL KOMMUNE Aabogen i Foldereid ......................... Nærøy Einviken ..................................... Flatanger Aadalen i Forradalen ...................... Stjørdal Ekne .......................................... Levanger Aarfor ............................................ Nærøy Elda ........................................ Namdalseid Aasen ........................................ Levanger Elden ...................................... Namdalseid Aasenfjorden .............................. Levanger Elnan ......................................... Steinkjer Abelvær ......................................... Nærøy Elnes .............................................. Verdal Agle ................................................ Snåsa Elvalandet .................................... Namsos Alhusstrand .................................. Namsos Elvarli .......................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug i Schognen ................. Levanger Elverlien ....................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug ................................. Levanger Faksdal ......................................... Fosnes Appelvær........................................ Nærøy Feltpostkontor no. III ........................ Vikna Asp ............................................. Steinkjer Feltpostkontor no. III ................... Levanger Asphaugen .................................. Steinkjer Finnanger ..................................... Namsos Aunet i Leksvik .............................. -

Utkast Til Disposisjon for Utredninger: Kunnskapsgrunnlag for Beslutning

Kommunereformen Rapport felles utredning for kommunene Frosta, Levanger, Verdal, Inderøy, Verran, Steinkjer, Snåsa og Namdalseid 14.09.2015 14.09.2015 INNHOLD 1 Sammendrag/konklusjon ............................................................................................................................. 2 2 Bakgrunn ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Om kommunereformen ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Kommunens ulike roller i lys av kommunereformen ......................................................................... 7 2.3 Beskrivelse av regionen .................................................................................................................... 11 2.4 Kommunale vedtak .......................................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Historisk bilde av kommuneinndelingen i regionen ......................................................................... 16 3 Utredningsalternativene ............................................................................................................................ 17 3.1 Alternativ 1: Inderøy, Steinkjer, Verran og Snåsa blir slått sammen til én kommune (4K) .............. 17 3.2 Alternativ 2: 4K minus Snåsa ........................................................................................................... -

Connected by Water, No Matter How Far. Viking Age Central Farms at the Trondheimsfjorden, Norway, As Gateways Between Waterscapes and Landscapes

Connected by water, no matter how far. Viking Age central farms at the Trondheimsfjorden, Norway, as gateways between waterscapes and landscapes Birgit Maixner Abstract – During the Viking Age, the Trondheimsfjorden in Central Norway emerges as a hub of maritime communication and exchange, supported by an advanced ship-building technology which offered excellent conditions for water-bound traffic on both local and supra-re- gional levels. Literary and archaeological sources indicate a high number of central farms situated around the fjord or at waterways leading to it, all of them closely connected by water. This paper explores the role of these central farms as gateways and nodes between waterscapes and landscapes within an amphibious network, exemplified by matters of trade and exchange. By analysing a number of case studies, their locations and resource bases, the partly different functions of these sites within the frames of local and supra-regional exchange networks become obvious. Moreover, new archaeological finds from private metal detecting from recent years indicate that bul- lion-based trivial transactions seem to have taken place at a large range of littoral farms around the Trondheimsfjorden, and not, as could be expected, only in the most important central farms or a small number of major trading places. Key words – archaeology; Viking Age; Norway; central farms; waterscapes; archaeological waterscapes; regional trade; exchange and communication; metal-detector finds; maritime cultural landscape; EAA annual meeting 2019 Titel – Durch Wasser verbunden. Wikingerzeitliche Großhöfe am Trondheimsfjord, Norwegen, als Tore und Verknüpfungspunkte zwischen Wasser- und Landwelten Zusammenfassung – Der Trondheimsfjord in Mittelnorwegen präsentiert sich während der Wikingerzeit als eine Drehscheibe für maritime Kommunikation und Warenaustausch, unterstützt durch eine hochentwickelte Schiffsbautechnologie, welche exzellente Voraussetzungen sowohl für den lokalen als auch den überregionalen Verkehr auf dem Wasser bot. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Velkommen Til Frøya Og Hitra

Velkommen til Frøya og Hitra Fakta – Frøya og Hitra • Frøya – den fremste øya • Hitra • 76 meter over havet • Befolkning: 5 088 (1.kv 2020) • 5400 små og store øyer, holmer og skjær • 231 km2 landareal • Pendling – ut: 429, inn: 516 • 2255 km kystlinje (2,7 % av Norges • 2 260 eneboliger kystlinje) • 1 927 fritidsboliger • Befolkning: 5 166 (1.kv 2020) • Pendling – ut: 390, inn: 660 • 1 990 eneboliger • 1 070 fritidsboliger Befolkningsutvikling Sysselsetting Prosentvis endring i antall sysselsatte 4.kvartal 2008 til 4. kvartal 2018 Utvikling i befolkning og sysselsetting i kommunene i Trøndelag 40,0 % Vekst befolkning Vekst befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser 30,0 % Skaun Frøya 20,0 % Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Melhus Hitra Vikna Levanger Orkdal 2019 (prosent) 2019(prosent) 10,0 % Klæbu Bjugn - Steinkjer Overhalla Verdal Ørland Frosta Midtre Gauldal Oppdal Namsos Åfjord Selbu Nærøy Inderøy Røros Grong Hemne Snillfjord Meldal 0,0 % Indre Fosen Agdenes Holtålen Høylandet Meråker Leka Rindal Flatanger Røyrvik Snåsa Roan Lierne Rennebu Namsskogan Osen Tydal Namdalseid -10,0 % Fosnes Endring Endring befolkning 2009 Verran -20,0 % Nedgang befolkning Nedgang befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser -30,0 % -20,0 % -10,0 % 0,0 % 10,0 % 20,0 % 30,0 % Endring sysselsetting 4.kvartal 2008-4. kvartal 2018 (prosent) Næringsliv • Hitra og Frøya står for: • ca. 51 % av eksporten av fisk fra Trøndelag • ca. 33 % av vareeksporten fra Trøndelag • ca. 18 % av den totale eksporten fra Trøndelag Helhetlig ROS • Risikokatalysatorer En risikokatalysator er en hendelse som kan påvirke en annen hendelse (som inntreffer samtidig) slik at konsekvensene av denne forsterkes. (..) Parallelle hendelser vil derfor kunne påvirke beredskapsevnen til kommunen opp mot kapasitet på ressursene. -

MNR Flatanger, Namdalseid, Fosnes, Namsos Og Overhalla Kommune

SMITTEVERNPLAN – MNR Flatanger, Namdalseid, Fosnes, Namsos og Overhalla kommune April 2008 Innholdsfortegnelse: 1 Innledning .....................................................................................3 1.1 Forord....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Oversikt over relevant lovverk................................................................................. 3 1.3 Definisjoner.............................................................................................................. 4 1.4 Kommunale oppgaver .............................................................................................. 4 1.5 Økonomi................................................................................................................... 5 2 Lokale forhold...............................................................................5 2.1 Demografiske data.................................................................................................... 5 3 Oversikt over personell og materiell i smittevernarbeidet........5 3.1 Smittevernleger - kommuneleger med ansvar for smittevern .................................. 5 3.2 Allmennleger............................................................................................................ 5 3.3 Helsestasjon.............................................................................................................. 6 3.3.1 Publikumsvaksinasjon.......................................................................................