The LLI Review: Fall 2011, Volume 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

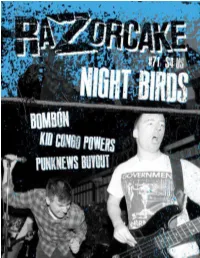

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

Brigadier General Randall K. "Randy" Bigum

BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM Retired Oct. 1, 2001. Brig. Gen. Randall K. "Randy" Bigum is director of requirements, Headquarters Air Combat Command, Langley Air Force Base, Va. As director, he is responsible for all functions relating to the acquisition of weapons systems for the combat air forces, to include new systems and modifications to existing systems. He manages the definition of operational requirements, the translation of requirements to systems capabilities and the subsequent operational evaluation of the new or modified systems. He also chairs the Combat Air Forces Requirements Oversight Council for modernization investment planning. He directs a staff of seven divisions, three special management offices and three operating locations, and he actively represents the warfighter in defining future requirements while supporting the acquisition of today's combat systems. The general was born in Lubbock, Texas. A graduate of Ohio State University, Columbus, with a bachelor of science degree in business, he entered the Air Force in 1973. He served as commander of the 53rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Bitburg Air Base, Germany, the 18th Operations Group at Kadena Air Base, Japan, and the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, S.C. He has served at Headquarters Tactical Air Command and the Pentagon, and at U.S. European Command in Stuttgart- Vaihingen where he was executive officer to the deputy commander in chief. The general is a command pilot with more than 3,000 flight hours in fighter aircraft. He flew more than 320 combat hours in the F- 15C during Operation Desert Storm. -

Music Preview

JACKSONVILLE NING! OPE entertaining u newspaper change your free weekly guide to entertainment and more | february 15-21, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com life in 2007 2 february 15-21, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents cover photo of Paul Paxton by: Dennis Ho feature NASCAR Media Day ............................................................................PAGES 16-17 Local Music Preview ...........................................................................PAGES 18-24 movies Breach (movie review) .................................................................................PAGE 6 Movies In Theatres This Week .................................................................PAGES 6-9 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted .......................................................................PAGE 7 Hannibal Rising (movie review) ....................................................................PAGE 8 The Last Sin Eater (movie review) ................................................................PAGE 9 Campus Movie Fest (Jacksonville University) ..............................................PAGE 10 Underground Film Series (MOCA) ...............................................................PAGE 10 at home The Science Of Sleep (DVD review) ...........................................................PAGE 12 Grammy Awards (TV Review) .....................................................................PAGE 13 Video Games .............................................................................................PAGE 14 food -

Hurlburt Field Is Located on the Gulf of Mexico in the Florida Panhandle, 35 Miles East of Pensacola, and Resides in the City of Mary Esther, Florida

Location: Hurlburt Field is located on the Gulf of Mexico in the Florida Panhandle, 35 miles east of Pensacola, and resides in the city of Mary Esther, Florida. Eglin AFB is a quick 20 minute drive. This area is also known as the Emerald Coast and is a major tourist attraction for its breathtaking white beaches and their famous emerald green waters. Cost of Living: The Okaloosa County, Florida is about U.S. average; recent job growth is positive; median household income (2016) is $57,655; unemployment rate 3.1%. Florida State tax 0%, sales tax currently 6%. Population: Active Duty Military 8,011 Civilian Employees 1,681 Family Members 8,703 Area Population: Okaloosa County 201,170, Santa Rosa County 170,497; Okaloosa County consists of Ft. Walton Beach, Destin, Crestview, Niceville, Shalimar, Mary Esther, Valparaiso, Laurel Hill, Cinco Bayou and Baker. Child Development Centers: Hurlburt's CDC offers services for children six weeks through 5 years of age. The program offers various services that include full-day care, hourly care and part-day preschool. By filling out a DD Form 2606, you can place your child's name on the child care waiting list in advance of your arrival. Call CDC West at 850-884-5154. Schools: There are no schools on base. Hurlburt Field is in Okaloosa County and the children living on base attending one of the following schools: Mary Esther or Florosa Elementary, Max Bruner Middle, and Fort Walton Beach High School. Many families live in the south end of Santa Rosa County in Navarre, west of Hurlburt Field. -

BFC 2016 Newspaper (11 X 17)

JOIN THOUSANDS AT THE NATION’S LARGEST EQUIPPING & RENEWAL CONFERENCE! EXTRAVAGANT GRACE JANUARY 29-31, 2016 EDMONTON, ALBERTA, CANADA EDMONTON EXPO CENTRE AT NORTHLANDS REGISTER NOW! SELLS OUT EARLY! www.breakforthcanada.com Super Early Bird............ Tues, Nov 24/15 Early Bird .......................... Tues, Dec 8/15 Regular...............................Tues, Jan 12/16 Walk-In (limited space)...... Fri, Jan 29/16 BOB JOHN PHILIP DANIELLE LEE 1 GOFF ORTBERG YANCEY STRICKLAND STROBEL WHO’S COMING? LOVE DOES THE LIFE YOU’VE WHAT’S SO AMAZING LIBERATING TRUTH THE CASE FOR CHRIST Artists & Speakers ALWAYS WANTED ABOUT GRACE 3 PRE-CONFERENCE INTENSIVE LEARNING WORKSHOPS 16 All-Day Workshops on Friday! PAUL CARLOS JOSH BRIAN BILL & PAM BALOCHE WHITTAKER MCDOWELL DOERKSEN & FARREL 4 “OPEN THE EYES OF MOMENT MAKER MORE THAN A The SHIYR Poets MEN ARE LIKE YOUTH MY HEART” CARPENTER “REFINER’S FIRE” WAFFLES – WOMEN & YOUNG ADULTS ARE LIKE SPAGHETTI iNFuZion (youth) PLUS... the EdgE (young adults) DR. GRANT & KATHY MULLEN HANS WEICHBRODT 5 JOE AMARAL MAIN CONFERENCE SHARON GARLOUGH BROWN CLASSES LINDA EVANS SHEPHERD GARY JON DR. MICHELLE DR. SEAN ARLEN SALTE Choose from CHAPMAN NEUFELD ANTHONY MCDOWELL ALPHA CANADA 130 Classes in 32 tracks THE FIVE LOVE STARFIELD SPIRITUAL PARENTING APOLOGETICS FOR A PROMISE KEEPERS LANGUAGES NEW GENERATION MUSICADEMY 8 CONFERENCE EXTRAS! Exhibit Show, Concerts, Late Night Events CONCERT CASTING CROWNS “WHO AM I” “THRIVE” 9–11 REGISTRATION & INFO www.breakforthcanada.com Group Rates as low as $99 DETAILS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. 1 FOR MORE INFO & ONLINE REGISTRATION GO TO BREAKFORTHCANADA.COM And you’ll experience so much more: from 180+ GRACE IS LIBERATING. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co.