Essential Criteria for Maximising the Playlist Potential of New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Coastal Dunedin

How to get ready and stay informed How to get ready: Stay informed: Prepare your family and household. Get together to develop and Radio frequencies: practice your emergency plan. Radio Dunedin (Dunedin 106.7FM & Assemble and maintain emergency 1305AM & Taieri 95.4FM) survival items. Have a getaway kit in More FM (97.4FM) case you must leave in a hurry. The Hits (89.4FM) Remember pets or livestock, include Magic Talk (96.6FM) them in your emergency planning. OAR FM (105.4FM) For pandemics, follow the official Newstalk ZB (1044AM) instructions from the Ministry of Health. Radio NZ National (101.4FM & 810AM) Keep your car ready: Television: Plan ahead for what you will do if you Southern Television are in your car when a disaster strikes. (Freeview Channel 39) In some emergencies you may be stranded in your vehicle for some Smart phone applications: time. A flood, snow storm or major Red Cross ‘Hazards’ app traffic accident could make it My Little Local impossible to proceed. MetService Consider having essential emergency items in your car and keep enough Web and Social Media: fuel in your car. www.otagocdem.govt.nz facebook.com/DnEmergency Assist vulnerable people in your family facebook.com/OtagoCDEM Community Guide to Emergencies or community: twitter.com/DnEmergency If you or a family member or twitter.com/OtagoCDEM neighbour have a disability or any Southern Coastal Dunedin special requirement that may affect Dunedin City Council: Waldronville to Kuri Bush your ability to cope in a disaster, Telephone: 03 477 4000 develop a support plan. www.dunedin.govt.nz Developed by the Southern Coastal Community Response Group and the Saddle Hill Community Board with support from Emergency Management Otago Get connected with those around you.. -

Hello, My Name Is Igor and I Am a Russian by Birth. I Have Read A

Added 31 Jan 2000 "Hello, My name is Igor and I am a Russian by birth. I have read a lot about Islam, I have Arabic and Chechen friends and I read a lot about the Holy Koran and its teaching. I resent the drunkenness and stupidity of the Russian society and especially the gorrilla soldiers that are fighting against the noble Mujahideen in Chechnya. I would like to become a Muslim and in connection with this I would like to ask you to give me some guidance. Where do I go in Moscow for help in becoming a Muslim. Inshallah I can accomplish this with your help." [Igor, Moscow, Russia, 28 Jan 2000] "May Allah help you brothers. I am from Kuwait. All Kuwaitis are with you. We hope for you to win this war, inshallah very soon. If you want me to do anything for you, please tell me. I really feel ashamed sitting in Kuwait and you brothers are fighting the kuffar (disbelievers). Please tell me if we can come there with you, can we come?" [Brothers R and R, Kuwait, 30 Jan 2000] "Salam my Brave Mujahadeen who are fighting in Chechnya and the ones administrating this web site. Every day I come to this site several time just to catch a glimpse of the beautiful faces whom Allah has embraced shahadah and to get the latest news. I envy you O Mujahadeen, tears run into my eyes every time I hear any news and see any faces on this site. My beloved brothers, Allah has chosen you to reawaken Muslims around the world. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 PDF 7.6 MB

Report NZ On Air Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2010 Report 2010 Table of contents He Rarangi Upoko Part 1 Our year No Tenei Tau 2 Highlights Nga Taumata 2 Who we are Ko Matou Noa Enei 4 Chair’s introduction He Kupu Whakataki na te Rangatira 5 Key achievements Nga Tino Hua 6 Television investments: Te Pouaka Whakaata 6 $81 million Innovation 6 Diversity 6 Value for money 8 Radio investments: Te Reo Irirangi 10 $32.8 million Innovation 10 Diversity 10 Value for money 10 Community broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho a-Iwi 11 $4.3 million Innovation 11 Diversity 11 Value for money 11 Music investments: Te Reo Waiata o Aotearoa 12 $5.5 million Innovation 13 Diversity 14 Value for money 15 Maori broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho Maori 16 $6.1 million Diversity 16 Digital and archiving investments: Mahi Ipurangi, Mahi Puranga 17 $3.6 million Innovation 17 Value for money 17 Research and consultation Mahi Rangahau 18 Operations Nga Tikanga Whakahaere 19 Governance 19 Management 19 Organisational health and capability 19 Good employer policies 19 Key financial and non financial measures and standards 21 Part 2: Accountability statements He Tauaki Whakahirahira Statement of responsibility 22 Audit report 23 Statement of comprehensive income 24 Statement of financial position 25 Statement of changes in equity 26 Statement of cash flows 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 Statement of service performance 43 Appendices 50 Directory Hei Taki Noa 60 Printed in New Zealand on sustainable paper from Well Managed Forests 1 NZ On Air Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2010 Part 1 “Lively debate around broadcasting issues continued this year as television in New Zealand marked its 50th birthday and NZ On Air its 21st. -

Let's Face It, the 1980'S Were Responsible for Some Truly Horrific

80sX Let’s face it, the 1980’s were responsible for some truly horrific crimes against fashion: shoulder-pads, leg-warmers, the unforgivable mullet ! What’s evident though, now more than ever, is that the 80’s provided us with some of the best music ever made. It doesn’t seem to matter if you were alive in the 80’s or not, those songs still resonate with people and trigger a joyous reaction for anyone that hears them. Auckland band 80sX take the greatest new wave, new romantic and synth pop hits and recreate the magic and sounds of the 80’s with brilliant musicianship and high energy vocals. Drummer and programmer Andrew Maclaren is the founding member of multi platinum selling band stellar* co-writing mega hits 'Violent', 'All It Takes' and 'Taken' amongst others. During those years he teamed up with Tom Bailey from iconic 80’s band The Thompson Twins to produce three albums, winning 11 x NZ music awards, selling over 100,000 albums and touring the world. Andrew Thorne plays lead guitar and brings a wealth of experience to 80’sX having played all the guitars on Bic Runga’s 11 x platinum debut album ‘Drive’. He has toured the world with many of New Zealand’s leading singer songwriter’s including Bic, Dave Dobbyn, Jan Hellriegel, Tim Finn and played support for international acts including Radiohead, Bryan Adams and Jeff Buckley. Bass player Brett Wells is a Chartered Director and Executive Management Professional with over 25 years operations experience in Webb Group (incorporating the Rockshop; KBB Music; wholesale; service and logistics) and foundation member of the Board. -

Pressreader: Corriere Della Sera - La Lettura, Sonntag, 13

PressReader: Corriere della Sera - La Lettura, Sonntag, 13. Januar 2019, Page 47 Nur zur DprivatenOMENICA 13 Verwendung. GENNAIO 2019 Gedruckt von PressReader CopyrightNur zur privaten © 2018 Verwendung. PressReader GedrucktInc. · http://about.pressreader.com von PressReader CopyrightNur zur privaten· [email protected]© 2018 Verwendung. PressReaderCORRIERE DELLA SGedrucktInc.ERA LA· http://about.pressreader.com LETTURA von PressReader47 CopyrightNur zur privaten· [email protected]© 2018 Verwendung. PressReader GedrucktInc. · http://about.pressreader.com von PressReader Copyright · [email protected]© 2018 PressReader Inc. · http://about.pressreader.com · [email protected] L’assalto del corsaro Anche quest’anno gli allievi dell’Accademia repertorio alla volontà di far conoscere un In punta di piedi ucraina di Balletto tornano al Teatro degli titolo non molto famoso. Danzeranno con di Giovanna Scalzo Arcimboldi (Milano) proponendo Le Corsaire. loro Karina Sarkissova e Ievgen Lagunov, Balletto del 1856, unisce la necessità dei primi ballerini dell’Opera di Budapest (18 e { giovani interpreti di misurarsi con il 19 gennaio, teatroarcimboldi.it). PERFORMANCE TOUR ITALIANO Sette ragazzine raccontano Avanguardia newyorchese iloromondi(eunfumetto) con il Very Practical Trio JAZZ he cosa sognano le teenager? Le risposte so- CIRCO uello di Michael Formanek (nella foto sot- no almeno sette, quante le adolescenti Q to, a destra), classe 1958, è un nome che C coinvolte nel progetto Le ragazzine stanno gli appassionati di jazz conoscono sin da- perdendo il controllo. La società le teme. La fine è gli anni Settanta, per aver letto il suo nome su azzurra, progetto teatrale people-specific ideato tantissimi dischi e per averlo ascoltato nei conte- TEENAGER e diretto da Eleonora Pippo, su una storia tratta sti più disparati, spesso comunicando un approc- dall’omonimo fumetto di Ratigher. -

Flip Grater 2011

EUROPEAN TOUR MARCH-APRIL FLIP GRATER 2011 Flip has delivered an album with a rare sensitivity .There are echoes in the delivery of the finest French singers a la Françoise Hardy and Carla Bruni- except Flip is singing in English. A beautiful rare gem. Roger Marbeck A beautifully crafted album by a songwriter who has honed her craft, presenting us with a album of substance, raw fragility and strength. This is her best work yet. – Jan Hellriegel “When you listen to Flip Grater you can’t help but fall in love with her a little bit. Her latest album is languid, smooth and delicious.” – Samantha Hayes, 3news The best art comes from suffering, so returning from Sweden in her twenties with a broken heart, music was her antidote. With over seven years of creating a sound Flip Grater is renowned for, the release of an EP, three critically acclaimed albums (2006's Cage For A Song, 2008's Be All And End All and 2010’s While I’m Awake I’m At War, a published book and a tour history that takes her meandering through 11 or so countries, Flip is seasoned. In 2006 her track Long Awaited Sigh turned heads across the folk and alt-country scene, with a track from it selected by producers of the hit US TV show Brothers and Sisters. This was followed by two trips to SXSW festival in Austin, TX with a showcase line-up including Luke Zimmerman and Kris Kristoffeson. Flip’s latest release While I’m Awake I’m At War has had NZ media calling her “the brunette¨ Stevie Nicks due to songs such as the single 'Careful', a meandering alt country ditty with a Fleetwood Mac feel. -

Dunedin Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZST) THURS SEP 20 2018 DUNEDIN COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 3 2018 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 2/2018 - 3/2018 This Survey Period: Sun Sep 10 to Sat Nov 18 2017 & Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Sep 1 2018 Last Survey Period: Sun Jul 2 to Sat Nov 18 2017 & Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 All 10+ People 10-17 People 18-34 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- Breeze 6.5 6.9 -0.4 8 8.4 8.7 -0.3 5.2 3.1 2.1 6.6 6.7 -0.1 9.1 9.4 -0.3 8.8 9.3 -0.5 5.3 6.0 -0.7 9.7 11.4 -1.7 Coast 3.8 3.5 0.3 13 0.8 0.7 0.1 1.2 1.0 0.2 1.9 1.8 0.1 1.7 1.7 0.0 5.5 6.0 -0.5 7.4 6.8 0.6 4.8 4.7 0.1 Edge 7.4 7.5 -0.1 4 18.4 15.8 2.6 12.2 15.3 -3.1 9.6 11.4 -1.8 8.5 8.6 -0.1 6.7 4.5 2.2 4.1 3.7 0.4 6.3 7.8 -1.5 Flava 4.2 4.8 -0.6 11 9.8 15.6 -5.8 10.8 11.2 -0.4 4.9 6.3 -1.4 4.1 4.7 -0.6 1.5 1.3 0.2 0.3 0.4 -0.1 3.7 5.8 -2.1 Life FM 1.4 0.5 0.9 16 3.5 * * 3.4 1.1 2.3 2.8 0.8 2.0 2.0 0.7 1.3 0.4 0.3 0.1 * * * 0.8 0.7 0.1 Magic 4.8 5.0 -0.2 10 * 0.5 * 1.3 0.5 0.8 1.4 0.9 0.5 3.1 2.7 0.4 7.6 8.7 -1.1 8.4 10.0 -1.6 6.8 5.7 1.1 More FM 7.3 7.3 0.0 6 7.3 9.5 -2.2 6.3 7.2 -0.9 11.3 11.5 -0.2 9.6 9.5 0.1 8.1 8.7 -0.6 7.5 7.1 0.4 10.1 9.2 0.9 Newstalk ZB 7.1 5.9 1.2 7 * * * 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.3 0.2 0.1 1.7 1.6 0.1 7.1 6.7 0.4 9.1 7.0 2.1 3.8 4.9 -1.1 Radio Dunedin 7.7 6.4 1.3 3 * * * 0.3 0.4 -0.1 0.2 0.4 -0.2 0.7 0.8 -0.1 9.0 5.5 3.5 18.8 15.7 3.1 2.2 1.0 1.2 -

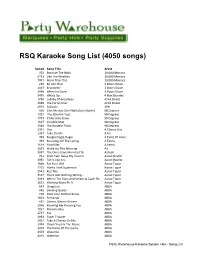

Karaoke 4050 Song List

RSQ Karaoke Song List (4050 songs) Song# Song Title Artist 302 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 2133 Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs 1901 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 285 Be Like That 3 Doors Down 2047 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down 3446 When Im Gone 3 Doors Down 3435 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes 1798 Lullaby Of Broadway 42nd Street 3089 The Partys Over 42nd Street 2879 Sukiyaki 4PM 866 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 1201 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 1373 If She Only Knew 98 Degrees 1687 Invisible Man 98 Degrees 3046 The Hardest Thing 98 Degrees 2331 One A Chorus Line 2937 Take On Me A Ha 393 Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste Of Hone 409 Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens 1619 Floorfiller A Teens 3563 Woke Up This Morning A3 3087 The One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah 762 Dont Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville 2951 Tell It Like It Is Aaron Neville 1646 For You I Will Aaron Tippin 1103 Honky Tonk Superman Aaron Tippin 2042 Kiss This Aaron Tippin 3147 There Aint Nothing Wrong... Aaron Tippin 3483 Where The Stars And Stripes & Eagle Fly Aaron Tippin 3572 Working Mans Ph.D. Aaron Tippin 543 Chiquitita ABBA 652 Dancing Queen ABBA 720 Does Your Mother Know ABBA 1603 Fernando ABBA 851 Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA 2046 Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA 1821 Mamma Mia ABBA 2787 Sos ABBA 2893 Super Trouper ABBA 2921 Take A Chance On Me ABBA 2974 Thank You For The Music ABBA 3078 The Name Of The Game ABBA 3370 Waterloo ABBA 4018 Waterloo ABBA Party Warehouse Karaoke System Hire - Song List Song# Song Title Artist 1660 Four Leaf Clover Abra Moore 2840 Stiff Upper Lip -

Les Artistes Néozélandais

NOTRE MONDE, 1 pays à la fois LES ARTISTES NÉOZÉLANDAIS TAWAROA KAWANA Né en 1995, il chante en anglais et en maori Demi-finaliste du Concours «New Zeland got talen»t, il a été le choix des juges Il a produit quelques singles, un 1e album est prévu pour 2015 CHANSON PRÉSENTÉE: AROHATIA TO REO, single enregistrée en 2013 MAISEY RIKA Chanteuse maori née en 1983 Elle chante professionnellement depuis l’âge de 13 ans Elle a produit 3 albums et nommée Meilleure voix féminine en 1998 CHANSON PRÉSENTÉE : TANGARA WHAKAMAUTAI, album Whitiora, 2012 LIAM FINN Né Liam Mullane Finn le 24 septembre 1983 Fils de Neil Finn, compositeur des chansons du film Le Hobbit Il a débuté sa carrière solo en 2007 en quittant son groupe Betchadupa CHANSON PRÉSENTÉE: SECOND CHANCE, album I’ll be lighting, 2007 LADYHAWK Née Philippa Brown en juillet 1979 Elle joue de 10 instruments et a produit l’ALBUM et le SINGLE de l’année en 2009 Son 1e groupe s’appelait Two lane backtop, elle a produit 3 albums et 8 singles à ce jour CHANSON PRÉSENTÉE: MY DELIRIUM, single enregistré en 2009 NOTRE MONDE, 1 pays à la fois WILLY MOON Né William George Sinclair le 2 juin 1989 Quitte l’école à 16 ans pour voyager en Europe, il s’établit en Grande-Bretagne Sa 1e chanson sort sur MySpace et lui amène son 1e contrat de disque, il a maintenant 2 albums et 6 singles CHANSON PRÉSENTÉE: RAIL ROAD TRACK, single enregistré en 2013 LORDE Née Ella Yelich O’Connor en 1996 Elle chante professionnellement depuis l’âge de 13 ans 1e album de 2 sorti en 2013, son 1e single «Royals» -

Apra Silver Scroll Awards Winners

APRA SILVER SCROLL AWARDS/50years 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 Wayne Kent-Healey Ray Columbus Roger Skinner David Jordan David Jordan Wayne Mason Corben Simpson Stephen Robinson Ray Columbus & Mike Harvey John Hanlon Teardrops I Need You Let’s Think of Something I Shall Take My Leave Out of Sight, Out of Mind Nature Have You Heard a Man Cry? Lady Wakes Up Jangles, Spangles and Banners Lovely Lady 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 John Hanlon Mike Harvey Lea Maalfrid Steve Allen Sharon O’Neill Paul Schreuder Phil Judd, Wayne Stevens Stephen Young Stephen Bell-Booth Hammond Gamble Windsongs All Gone Away Lavender Mountain Why Do They? Face In a Rainbow You’ve Got Me Loving You & Mark Hough I Can’t Sing Very Well All I Want Is You Look What Midnight’s Counting The Beat Done to Me 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 Malcom Black Tony Waine Dave Dobbyn Shona Laing Stephen Bell-Booth Guy Wishart Rikki Morris Shona Laing Dave Dobbyn Don McGlashan & Nick Sampson Abandoned By Love You Oughta Be In Love Soviet Snow Hand It Over Don’t Take Me For Granted Heartbroke Mercy of Love Belle of the Ball Anchor Me For Today 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 Strawpeople Bic Runga Greg Johnson Dave Dobbyn Bill Urale Chris Knox Neil Finn Che Ness & Godfrey de Grut Nesian Mystik Scribe Sweet Disorder Drive Liberty Beside You Reverse Resistance My Only Friend Turn and Run Misty Frequencies For the People Not Many 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 Evermore Don McGlashan Brooke Fraser Opshop James Milne & Luke Buda The Naked and Famous Dave Baxter Stephanie Brown Ella Yelich-O’Connor Tami & Joshua Neilson It’s Too Late Bathe In the River Albertine One Day Apple Pie Bed Young Blood Love Love Love Everything To Me & Joel Little Walk (Back To Your Arms) Royals. -

Total Nz Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZST) THURS APR 29 2021 TOTAL NZ COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 1 2021 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 4/2020 - 1/2021 This Survey Period: Metro - Sun Sept 13 to Sat Nov 14 2020 & Sun Jan 31 to Sat Apr 10 2021/ Regional - Sun Jan 19 to Sat Mar 28 2020 & Sun Jul 19 to Sat Nov 14 2020 & Sun Jan 31 to Sat Apr 10 2021 *Auckland, Northland, Tauranga & Waikato Wave 1 field dates Sun Feb 14 to Sat Apr 10 2021 Last Survey Period: Metro - Sun July 19 to Sat Nov 14 2020/ Regional - Sun Aug 25 to Sat Nov 2 2019 & Sun Jan 19* to Sat Mar 28 2020 & Sun July 19 to Sat Nov 14 2020 *Northland, Tauranga & Waikato Wave 1 field dates Feb 2 to Mar 28 2020 All 10+ People 10-24 People 18-39 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- Network Breeze 9.5 9.1 0.4 2 5.9 4.5 1.4 6.7 5.9 0.8 8.6 7.0 1.6 9.5 8.4 1.1 11.7 12.1 -0.4 11.0 13.2 -2.2 9.2 10.1 -0.9 Network Coast 5.8 6.2 -0.4 9 2.2 2.4 -0.2 2.9 3.1 -0.2 3.1 3.5 -0.4 4.1 4.4 -0.3 7.0 8.0 -1.0 8.9 10.3 -1.4 4.8 4.5 0.3 Network The Edge 6.1 6.0 0.1 8 14.2 13.5 0.7 11.6 10.8 0.8 9.1 9.3 -0.2 7.4 7.7 -0.3 3.4 3.5 -0.1 1.8 1.5 0.3 8.2 8.3 -0.1 Network Flava 1.3 2.0 -0.7 15 2.8 5.1 -2.3 3.0 4.3 -1.3 2.4 2.9 -0.5 1.8 2.4 -0.6 0.6 1.1 -0.5 0.2 0.3 -0.1 1.6 2.6 -1.0 Network George FM 1.9 1.8 0.1 13 2.9 2.3 0.6 4.4 4.1 0.3 3.9 3.9 0.0 3.0 3.0 0.0 1.1 0.9 0.2 0.5 0.3 0.2 1.4 1.6 -0.2 Network Gold* 1.2 0.9 0.3 16 1.0 0.4 0.6 -

DX Times Master Page Copy

N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times N.Z. RADIO Monthly journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est. 1948) D X July 2004 - Volume 56 Number 9 LEAGUE http://radiodx.com LEAGUE Contribution deadline for next issue is Wed 4th August 2004 PO Box 3011, Auckland CONTENTS FRONT COVER REGULAR COLUMNS Bandwatch Under 9 3 An Advertisement from ‘The New Zealand with Ken Baird Radio Times’ 1936 Bandwatch Over 9 8 with Stuart Forsyth Fcst SW Reception 12 Compiled by Mike Butler English in Time Order 13 Shortwave Bandwatch Over 9 with Yuri Muzyka A reminder that Stuart Forsyth is now doing the Shortwave Mailbag 15 Bandwatch Over 9 and you can send your notes with Laurie Boyer to Stuart at Shortwave Report 15 with Ian Cattermole’ c/- NZRDXL, P.O.Box 3011, Auckland Utilities 21 with Evan Murray or direct to TV/FM 23 27 Mathias Street with Adam Claydon Darfield 8172 Broadcast news/DX 32 with Tony King E-mail: US X Band List 37 [email protected] Compiled by Tony King or ADCOM News 41 [email protected] with Bryan Clark Branch News 43 with Chief Editor Coming up in next Month’s Magazine OTHER August League Subscription 25 Form Remember to update your Ladder totals Questionnaire 26 Stuart Forsyth MarketSquare 36 c/- NZRDXL, P.O.Box 3011, Auckland Waianakarua Winter 38 or direct to Solstice Trail Stuart Forsyth by Paul Ormandy 27 Mathias Street Random Thoughts- 43 Darfield 8172 Let's dump 'DX' and E-mail: [email protected] kill the 'QSL' from our vocabulary by David Ricquish League Subscription Form and Questionnaire Page 25/26 Please remember to pay your subscription if it is due and also fill out the questionnaire.