How a Smiley Face Can Save the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economics & Finance 2011

Economics & Finance 2011 press.princeton.edu Contents General Interest 1 Economic Theory & Research 15 Game Theory 18 Finance 19 Econometrics, Mathematical & Applied Economics 24 Innovation & Entrepreneurship 26 Political Economy, Trade & Development 27 Public Policy 30 Economic History & History of Economics 31 Economic Sociology & Related Interest 36 Economics of Education 42 Classic Textbooks 43 Index/Order Form 44 TEXT Professors who wish to consider a book from this catalog for course use may request an examination copy. For more information please visit: press.princeton.edu/class.html New Winner of the 2010 Business Book of the Year Award, Financial Times/Goldman Sachs Fault Lines How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy Raghuram G. Rajan “What caused the crisis? . There is an embarrassment of causes— especially embarrassing when you recall how few people saw where they might lead. Raghuram Rajan . was one of the few to sound an alarm before 2007. That gives his novel and sometimes surprising thesis added authority. He argues in his excellent new book that the roots of the calamity go wider and deeper still.” —Clive Crook, Financial Times Raghuram G. Rajan is the Eric J. Gleacher Distinguished Service Profes- “Excellent . deserve[s] to sor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and be widely read.” former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. —Economist 2010. 272 pages. Cl: 978-0-691-14683-6 $26.95 | £18.95 Not for sale in India ForthcominG Blind Spots Why We Fail to Do What’s Right and What to Do about It Max H. Bazerman & Ann E. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Connections in Transportation Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT, Spring 2015

Behavior and Policy 11.478 Behavior and Policy: Connections in Transportation Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT, Spring 2015 Full Reading List Part I: Behavior and Policy in a Nutshell Class 1. Cafeteria Trays and Multiple Frameworks • Etheredge (1976) The case of the unreturned cafeteria trays: An Investigation based upon theories of motivation and human behavior Class 2. Ten Instruments for Behavioral Change • Miller and Prentice (2013) Psychological Levers of Behavior Change, Chapter 17 in Eldar Shafir, The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy • Richard Thaler, Cass R. Sunstein: Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Introduction • Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow, Introduction Class 3. Measurement, Tools and Technology (Emile Bruneau) • Emile Bruneau 2015 "Putting Neuroscience to Work for Peace”, Working Paper • Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kremer, M. (2007). Using randomization in development economics research: A toolkit. Handbook of development economics, 4, 3895-3962. • Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(2), 197. You may try the Implicit Association Test here https://implicit.harvard.edu/ • Winter Mason and Siddharth Suri (2012) Conducting Behavioural Research on Amazon’s Mech Turk, Behavior Research Method 44(1) Class 4. My Brain at the Bus Stop: EEG & Waiting • Dan Ariely and Gregory S. Berns (2010), “Neuromarketing: The Hope and Hype of Neuroimaging in Business.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience. • Li, Zelin, F. Duarte, J. Zhao, Z. Zhao (2015) My brain at the bus stop: an exploratory framework for applying EEG-based emotion detection techniques in transportation study, working paper Class 5. -

Sendhil Mullainathan Education Fields of Interest Professional

Sendhil Mullainathan Robert C Waggoner Professor of Economics Littauer Center M-18 Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] 617 496 2720 _____________________________________________________________________________________ Education HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MA, 1993-1998 PhD in Economics Dissertation Topic: Essays in Applied Microeconomics Advisors: Drew Fudenberg, Lawrence Katz, and Andrei Shleifer CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NY, 1990-1993 B.A. in Computer Science, Economics, and Mathematics, magna cum laude Fields of Interest Behavioral Economics, Poverty, Applied Econometrics, Machine Learning Professional Affiliations HARVARD UNIVERSITY Robert C Waggoner Professor of Economics, 2015 to present. Affiliate in Computer Science, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, July 1, 2016 to present Professor of Economics, 2004 (September) to 2015. UNVIRSITY OF CHICAGO Visiting Professor, Booth School of Business, 2016-17. MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Associate Professor, 2002-2004 Mark Hyman Jr. Career Development Assistant Professor, 2000-2002 Assistant Professor, 1998- 2000 SELECTED AFFILIATIONS Co - Founder and Senior Scientific Director, ideas42 Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research Founding Member, Poverty Action Lab Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Contributing Writer, New York Times Sendhil Mullainathan __________________________________________________________________ Books Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, joint with Eldar Shafir, 2013. New York, NY: Times Books Policy and Choice: Public Finance through the Lens of Behavioral Economics, joint with William J Congdon and Jeffrey Kling, 2011. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press Work in Progress Machine Learning and Econometrics: Prediction, Estimation and Big Data, joint with Jann Spiess, book manuscript in preparation. “Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Experiments: A Machine Learning Approach,” joint with Jens Ludwig and Jann Spiess, in preparation. -

Predictions and Nudges: What Behavioral Economics Has to Offer the Humanities, and Vice-Versa

Book Review Predictions and Nudges: What Behavioral Economics Has to Offer the Humanities, and Vice-Versa Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Pp. 304. $26.00. Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. New York: HarperCollins, 2008. Pp. 280. $25.95. Anne C. Dailey* Peter Siegelman** Rationalists, wearing square hats, Think, in square rooms, Looking at the floor, Looking at the ceiling. They confine themselves To right-angled triangles. If they tried rhomboids, Cones, waving lines, ellipses- As, for example, the ellipse of the half-moon- Rationalists would wear sombreros.1 Evangeline Starr Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, University of Connecticut School of Law. ** Roger Sherman Professor of Law, University of Connecticut School of Law. We thank Ellen Siegelman for helpful comments. 1. Wallace Stevens, Six Significant Landscapes, VI, HARMONIUM (1916). Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities, Vol. 21, Iss. 2 [2009], Art. 6 Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities [21:2 The informed law and humanities reader can hardly fail to be aware that the field of economics has undergone a "behavioral revolution" over the past several decades, and that this revolution has spilled over into the legal academy. Open an economics journal these days and you are likely to find any number of articles billing themselves as "behavioral" in orientation. Similarly, law reviews are filled with articles bearing titles ranging from "A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics"'2 to "Harnessing Altruistic Theory and Behavioral Law and Economics to Rein in Executive Salaries" 3 and "Some Lessons for Law from Behavioral Economics About Stockbrokers and Sophisticated Customers. -

Dan Ariely Alfred P

Dan Ariely Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Behavioral Economics Curriculum Vitae [Updated October 2007] Education Duke University, The Fuqua School of Business, Durham, NC Ph.D., Business Administration, August 1998. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC Ph.D., Cognitive Psychology, August 1996 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC M.A., Cognitive Psychology, August 1994 Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel B.A., Psychology, June 1991 Personal Convincing Sumi to marry me Achievements Amit (2002) Neta (2006) Employment 2007 – Current: Duke University, Fuqua School of Business & The Center for Cognitive Neuroscience (visiting Professor) 1998 – Current: MIT, Sloan School of Management & the Media Laboratory Other 2001-2002: University of California at Berkeley appointments 2004 (Summer): The Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford 2005-2007: The Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Published Dan Ariely (Forthcoming) “Customers’ Revenge 2.0” Harvard Business Papers Review. Dan Ariely and Michael Norton. (Forthcoming) “Psychology and Experimental Economics: A Gap in Abstraction” Current Directions in Psychological Science. Jeana Frost, Zoë Chance, Michael Norton and Dan Ariely. (Forthcoming) “People are Experience Goods: Improving Online Dating with Virtual Dates” Journal of Interactive Marketing. Ariely CV - 1 - Dan Ariely, Emir Kamenica and Drazen Prelec. (Forthcoming) “Man’s Search for Meaning: The Case of Legos.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. Kristina Shampan’er and Dan Ariely. (Forthcoming) “How Small is Zero Price? The True Value of Free Products.” Marketing Science. Uri Simonsohn, Niklas Karlsson, George Loewenstein and Dan Ariely. (Forthcoming) “The Tree of Experience in the Forest of Information: Overweighing Personal Relative to Vicarious Experience.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. -

People Are Experience Goods: Improving Online Dating with Virtual Dates

PEOPLE ARE EXPERIENCE GOODS: IMPROVING ONLINE DATING WITH VIRTUAL DATES JEANA H. FROST, ZOË CHANCE, MICHAEL I. NORTON, AND DAN ARIELY JEANA H. FROST is a Research Scientist e suggest that online dating frequently fails to meet user expecta- with PatientsLikeMe.com; W e-mail: [email protected] tions because people, unlike many commodities available for purchase online, are experience goods: Daters wish to screen potential romantic partners by ZOË CHANCE is a graduate student at the Harvard experiential attributes (such as sense of humor or rapport), but online dating Business School; e-mail: [email protected] Web sites force them to screen by searchable attributes (such as income or reli- gion). We demonstrate that people spend too much time searching for MICHAEL I. NORTON options online for too little payoff in offline dates (Study 1), in part because is Assistant Professor of Business Administration at the users desire information about experiential attributes, but online dating Web Harvard Business School; e-mail: [email protected] sites contain primarily searchable attributes (Study 2). Finally, we introduce and beta test the Virtual Date, offering potential dating partners the opportu- DAN ARIELY is Professor of Marketing at nity to acquire experiential information by exploring a virtual environment in The Fuqua School of Business, Duke University; interactions analogous to real first dates (such as going to a museum), an e-mail: [email protected] online intervention that led to greater liking after offline meetings (Study 3). This work is based in part on Jeana Frost’s doctoral dissertation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. -

Ziv Carmon's Curriculum Vitae

Ziv Carmon’s Curriculum Vitae Phone: +65 6799 5337 Address: INSEAD, 1 Ayer Rajah Ave., Singapore 138676 email: ziv.carmon at insead.edu & ziv.carmon at gmail.com Academic Appointments 2017 Dean of Research, INSEAD. 2017 The INSEAD Alfred H. Heineken Chaired Professor of marketing. 2012 The INSEAD Chaired Professor of Marketing in Memory of Erin Anderson. 2006 Professor of Business Administration, INSEAD. 2000 Associate Professor of Business Administration, INSEAD. 1993 Assistant Professor of Business Administration (Marketing), Fuqua School of Business, Duke University; Promoted to Associate Professor in 1997. Education 1993 Ph.D. in Business Administration, Haas School of Business, University of California- Berkeley; Thesis advisers: Daniel Kahneman & Itamar Simonson. 1990 M.S. in Business Administration, Haas School of Business, University of California- Berkeley. 1986 B.Sc. in Industrial Engineering (Cum Laude), Technion- I.I.T. Awards and Honors (since 2006) 2022 Conference co-Chair, The Choice Symposium. Invited Speaker, The Invitational Choice Symposium (2019, 2016, 2010, 2007, 2004, 2001, 1997, 1994); 2020 Doctoral Consortium Faculty, Association of Consumer Research (also in 2018, 2017, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005); Society of Consumer Psychology (2009); American Marketing Association (2007, 2005); European Marketing Association Conference (2008, 2006); 2019 Deans’ Commendation for Excellence in MBA Teaching (also in 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011); 2017 Competitive Research Grant of S$783,120, for the RCT study Promoting Green Mobility; 2014 Certificate of Recognition for Outstanding MBA Teaching; 2012 Competitive Research Grant by the Institute on Asian Consumer Insight; 2011 Supervised the Winner of the Association of Consumer Research/Sheth Foundation Dissertation Award in Public Purpose Consumer Research; 2010 Winner, William F. -

Economics and Human Nature

Rethinking Rationality Economics and Human Nature When it comes to many of By James Guszcza our economic IN HIS RECENT book, Predictably Irrational: decisions, are The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, the behavioral economist Dan Ariely describes an ad for The Economist that we predictably offered the following three subscription options: 1. Internet-only access: $59 irrational? 2. Printed edition: $125 3. Printed edition plus Internet access: $125 Can a nudge This seems strange. Why would the marketing “boffins” at The Economist offer an option that clearly offers fewer in the right benefits for the same price? Wouldn’t offering Options 1 and 3 achieve the same results? direction help? Not necessarily. Ariely had a theory about this that he put to the test. He offered 100 of his students at the Mas- sachusetts Institute of Technology the choice between Op- tions 1, 2, and 3 and found that most were inclined to take Option 3: ■■ Option 1–16 students ■■ Option 2–0 students ■■ Option 3-84 students. Of course, nobody chose Option 2. Next, Ariely dropped Option 2 and offered the students the choice between Op- tions 1 and 3. Removing the obviously inferior Option 2 should have had no effect on the students’ choices. But Ari- ely’s result was striking: ■■ Option 1–68 students ■■ Option 2 ■■ Option 3–32 students Even though Option 2 was a decoy that no one would select, its mere presence apparently had the powerful effect of “nudging” buyers to opt for the more expensive Option 3. Option 2 provided a basis for comparison against which Option 3 looked good; but no such basis for comparison was SON provided for Option 1. -

![Dan Ariely Curriculum Vitae [Updated May 2016]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7838/dan-ariely-curriculum-vitae-updated-may-2016-2307838.webp)

Dan Ariely Curriculum Vitae [Updated May 2016]

Dan Ariely Curriculum Vitae [Updated May 2016] Current 2008 – Current Appointments Duke University, James B. Duke Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics 2008 – Current Senior Fellow, Duke University Kenan Institute for Ethics 2015 – Current Faculty Director, Washington University in St. Louis: George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Envolve Center for Health Behavior Change 2016 – Current Visiting Professor, AMC-UvA Education Duke University, The Fuqua School of Business, Durham, NC Ph.D. Business Administration, August 1998. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC Ph.D. Cognitive Psychology, August 1996 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC M.A. Cognitive Psychology, August 1994 Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel B.A. Psychology, June 1991 Personal Achievements Convincing Sumi to marry me Amit (2002) Neta (2006) Other Appointments 2001 – 2002: University of California at Berkeley 2004 (Summer): Stanford, The Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences 2005 – 2007: Princeton, The Institute for Advanced Study 1998 – 2008: MIT, Sloan School of Management Ariely CV Page 1 2000 – 2010: MIT, The Media Laboratory Published Daniel Mochon, Karen Johnson, Janet Schwartz, and Dan Ariely Papers (Forthcoming) “What Are Likes Worth? A Facebook page field experiment.” Journal of Marketing Research. Dan Ariely, Anat Bracha, and Jean-Paul L’Huillier (Forthcoming) “Public and Private Values.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. Heather Mann, Ximena Garcia-Rada, Lars Hornuf, Juan Tafurt, and Dan Ariely (2016), “Cut from the Same Cloth: Similarly Dishonest Individuals Across Countries.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Daniel Mochon, Janet Schwartz, Josiase Maroba, Deepak Patel, and Dan Ariely (2016), “Gain without pain: The Extended Effects of a Behavioral Health Intervention.” Management Science. -

Law, Behavior, and Financial Re-Regulation

Buffalo Law Review Volume 57 Number 5 Article 2 12-1-2009 Trust in the Shadows: Law, Behavior, and Financial Re-Regulation Raymond H. Brescia Albany Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Law and Economics Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Raymond H. Brescia, Trust in the Shadows: Law, Behavior, and Financial Re-Regulation, 57 Buff. L. Rev. 1361 (2009). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol57/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 57 DECEMBER 2009 NUMBER 5 Trust in the Shadows: Law, Behavior, and Financial Re-Regulation RAYMOND H. BRESCIAt INTRODUCTION In the deep throes of the Great Depression, in an effort to restore faith in America's economy, the Roosevelt Administration promoted, and Congress authorized, the development of voluntary codes of conduct to govern employment and manufacturing practices across hundreds of industries. Compliance with these codes allowed companies to display a "Blue Eagle" decal on the shop floor, in their shop windows, and anywhere else their employees might work or the general public might come across their products. This symbol announced to the world that an employer was "doing its part" for the national recovery effort and was a business worthy of consumer trust. -

Behavioral Economics Syllabus

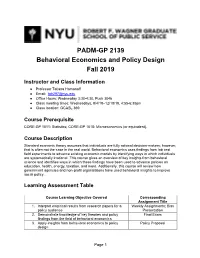

PADM-GP 2139 Behavioral Economics and Policy Design Fall 2019 Instructor and Class Information ● Professor Tatiana Homonoff ● Email: [email protected] ● Office Hours: Wednesday 3:30-4:30, Puck 3046 ● Class meeting times: Wednesdays, 9/4/19–12/18/19, 4:55-6:35pm ● Class location: GCASL 369 Course Prerequisite CORE-GP 1011: Statistics; CORE-GP 1018: Microeconomics (or equivalent). Course Description Standard economic theory assumes that individuals are fully rational decision-makers; however, that is often not the case in the real world. Behavioral economics uses findings from lab and field experiments to advance existing economic models by identifying ways in which individuals are systematically irrational. This course gives an overview of key insights from behavioral science and identifies ways in which these findings have been used to advance policies on education, health, energy, taxation, and more. Additionally, this course will review how government agencies and non-profit organizations have used behavioral insights to improve social policy. Learning Assessment Table Course Learning Objective Covered Corresponding Assignment Title 1. Interpret empirical results from research papers for a Weekly Assignments; Bias policy audience Presentation 2. Demonstrate knowledge of key theories and policy Final Exam findings from the field of behavioral economics 3. Apply insights from behavioral economics to policy Policy Proposal design Page 1 Required Readings Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, 2008. Excerpts from the following books (provided on NYU Classes): o Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. Hereafter, referred as TFS.