Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood, Leuven University Press, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TXINITXI TEAM Capitán: Raúl Vela

TXINITXI TEAM capitán: Raúl Vela Raúl "Feytor" Vela - Undiying Dinasties Jorge “Orombi” García, Dread elves 525 death cult hierarch: general, soul conduit, wizard máster 4 spells divination, sacred hourglass, 745 - Cult Priest, BSB, Shield, Cult of Yema, Paired Weapons (Divine altar), Basalt Infusion, binding scroll Lucky Charm, Moraec's Reaping 280 death cult hierarch: hierophant, wizard adept 2 spells cosmology, book of arcane power 450 - Oracle, General, 4 spells, Wizard Master, Alchemy, Binding scroll 125 death cult hierarch: wizard apprentice 1 spells evocatión 2x160 - 5x Dark Raiders 160 tomb architect 420 - 25x Dread Legionnaires: Spears, C,S, Flaming Standard 285 nomarch on skeletal chariot: steeds of nephet-ra, death mask of teput 2x195 - 15xDread Legionnaires: Spears 210 20 skeletons: s banner of the relentless company 571 - 23xDancers of Yema: C,S, Rending Banner 505 6 skeleton chariots: c 135 - Medusa: Halaberd 290 3 skeleton chariots 3x 195 - Raptor Chariot 130 5 skeleton scouts 2x 440 - Hydra 390 4 tomb cataphracts 4496 155 3 great cultures 685 8 shabti archers: s rending banner Iban "Gorras Toretto" Eraña Kingdom of Equitaine 440 6 shabti archers 680-Duke on Pegasus: General, questing oath,basalt infusion,divine judment, lucky charm, 160x2 2x1 sand scorpion potion of swiftness, fortres of faith,virtue Total:4500 of might,shield,lance 315-Paladin on barded warhorse: (bsb),questing oath,alchemist alloy, Flaming Stanford, shield Josu "epoepo" García - The Vermin Swarm 490-Damsel on barded warhorse: wizard master,druidism, Magical -

Dan Dare the 2000 Ad Years Vol. 01 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAN DARE THE 2000 AD YEARS VOL. 01 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pat Mills | 320 pages | 05 Nov 2015 | Rebellion | 9781781083499 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Dan Dare The 2000 AD Years Vol. 01 PDF Book I guess I'd agree with some of the comments about the more recent revival attempts and the rather gauche cynicism that tends to pervade them. Thanks for sharing that, it's a good read. The pen is mightier than the sword if the sword is very short, and the pen is very sharp. The cast included Mick Ford Col. John Constantine is dying. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Hardcover , pages. See all 3 brand new listings. Al rated it really liked it Feb 06, Archived from the original PDF on The stories were set mostly on planets of the Solar System presumed to have extraterrestrial life and alien inhabitants, common in science fiction before space probes of the s proved the most likely worlds were lifeless. Mark has been an executive producer on all his movies, and for four years worked as creative consultant to Fox Read full description. Standard bred - ; vol. The first Dan Dare story began with a starving Earth and failed attempts to reach Venus , where it is hoped food may be found. You may also like. Ian Kennedy Artist. Pages: [ 1 ] 2. SuperFanboyMan rated it really liked it Jul 16, In Eagle was re-launched, with Dan Dare again its flagship strip. John Wiley and Sons, Author : Michigan State University. In a series of episodic adventures, Dare encountered various threats, including an extended multi-episode adventure uniting slave races in opposition to the "Star Slayers" — the oppressive race controlling that region. -

El Cómic Y Su Relación Con El Arte En Fotogramas the Comic and Its Relationship with Art in Frames

El cómic y su relación con el arte en fotogramas The comic and its relationship with art in frames AUTORES: Montalvo, Blanca Profesora Titular de Universidad. Dep. de Arte y arquitectura. Facultad de Bellas Artes. Universidad de Málaga Martínez Silvente, María Jesús Profesora Titular de Universidad. Dep. de Historia del Arte. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Universidad de Málaga PALABRAS CLAVE: Cómic, vídeo, fotografía, narración, instalación KEY WORDS: Comic, video, photography, storytelling, instalation RESUMEN: Esta comunicación se centra en el cómic y su relación con la fotografía. Proponemos analizar el lenguaje de la fotonovela como un formato transmedia entre el cómic, el cine, la instalación y el vídeo arte. También apostamos por una recuperación del formato, en la era de la imagen digital. Para llevarlo a cabo, analizamos las propuestas más experimentales desarrolladas desde mediados del siglo pasado, herederas de las publicadas en Help! (1960-1965) y Punk Magazine, (1978-1981). Desde Weirdo (1981- 1993), a la historia juvenil Doomlord, publicada en la revista Eagle (1982-1989), hasta las más recientes El fotógrafo (2003) de Lefèvre/ Guibert/ Lemercier y La grieta (2017) de Spottorno y Abril. Comparamos estas prácticas con obras de cine y arte que también desarrollan la narración mediante la utilización de imagen fija (fotografía o diapositivas), como las película de Chris Maker o Robert Smithson, las instalaciones de James Coleman o Nan Goldin, los flipbooks de Miguel Roschild, o el cine con múltiples pantallas de Jean Luc Godard y Lev Manovich. Para finalizar comentamos nuestro proyecto en proceso: La Súper Fotonovela. ABSTRACT: This communication focuses on comics and their relationship with photography. -

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: the Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: The Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63 Howard Cox and Simon Mowatt Britain’s newspaper and magazine publishing business did not fare particularly well during the 1950s. With leading newspaper proprietors placing their desire for political influence above that of financial performance, and with working practices in Fleet Street becoming virtually ungovernable, it was little surprise to find many leading periodical publishers on the verge of bankruptcy by the decade’s end. A notable exception to this general picture of financial mismanagement was provided by the chain of enterprises controlled by Roy Thomson. Having first established a base in Scotland in 1953 through the acquisition of the Scotsman newspaper publishing group, the Canadian entrepreneur brought a new commercial attitude and business strategy to bear on Britain’s periodical publishing industry. Using profits generated by a string of successful media activities, in 1959 Thomson bought a place in Fleet Street through the acquisition of Lord Kemsley’s chain of newspapers, which included the prestigious Sunday Times. Early in 1961 Thomson came to an agreement with Christopher Chancellor, the recently appointed chief executive of Odhams Press, to merge their two publishing groups and thereby create a major new force in the British newspaper and magazine publishing industry. The deal was never consummated however. Within days of publicly announcing the merger, Odhams found its shareholders being seduced by an improved offer from Cecil King, Chairman of Daily Mirror Newspapers, Ltd., which they duly accepted. The Mirror’s acquisition of Odhams was deeply controversial, mainly because it brought under common ownership the two left-leaning British popular newspapers, the Mirror and the Herald. -

Eagle 1919 Lent

____,1 --------�----�--------�-------------------1 11 Jl!tnga!int �uppotttb b!l �tmbtrll of �t �obn'i Qtolhgt 1�rinteb for :;bubsmlbers onl)} <!t:ambrll:Jge lE. �obn55on, t!I:tinit!l �luet l�t!nUll bl! fllttcal!e k Ql:o. 1:(mite'l:l, lRose Ql:usunt 1919 'F"olumr *iL 80 Tht Library. *Glover (T. R.). From Pericles to Philip. Svo. Loncl. 1917. 18.14.42. Ilaskins (C. H.). The Nonnans in European History. 8vo. Boston 1915. 20.5.43. Historical Society (Royal). Camdcn 3rc1 Series. Vol. XXVIII. The autobiography of Thomas Raymoncl, and memoirs of the family of Guise of Elmore, Gloucestershire. Edited by G. Davies. 4to. Land. 1917. 5.17.192. 1-lovell (M.). The Chartist Movement. Edited and completed, with a memoir, by T. F. Tout. 8vo. Manchester, 1918. 1.37.76. Kirk (Roberl). The Secret Commonwc�lh of Elves, Fauns and Fairies. A study in folk-lore and p}1'fs.£:hial research. The text by R. Kirk, ,1.0. 1691 ; the comment by Andrew Lang. (Bibliotheque de Carabas). 8vo. Land. 1893. Kirkaldy (A. W.). Industry and Finance: War expedi(;nts and recon struction. Being the results of inquiries arranged by the seclion of THE EAGLE. Economic Science and Statistics of the British Association during 1916 and 1917. Edited by A. W. K. 8vo. Land. [1917]. Lang (Andrew). A history of Scotland from the Homan occupation. 4 vols. (Vol. II, 3rd edition). Svo. Ec!in. 1900-1907. 5.33.12-15. Palaeontographical Society. Vol. LXX. Issued for 1916. fol. Land. 1918. 13.2.22. Pcpys (Samuel). -

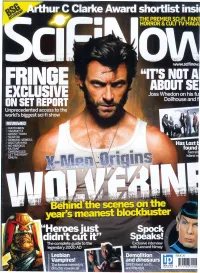

COMICS+Scifinow+Feature+On+

Comics-wise, France's Metal Hurlantand the pre-superhero American tradition (Weird, Eerie) provided his inspiration. During this remarkably long gestation period - partly the result of missing a launch deadline, partly Sanders apprehending Mills was cooking up "something special" - a hiccup occurred when a public outcry followed not long after the February '76 launch of Mills's revolutionarily gory and anti-authority Action. That October, Action was briefly taken off the stands to be cleaned up. "The disastrous press obviously had an effect on 2000 AD and stories that were originally much tougher and much harder suddenly had to be toned down," says Mills. Nonetheless, 2000 AD would remain an edgy concoction: "Action had very much a street consciousness and there's a spillover of that into 2000 AD." Additionally, "You wrote a character with some humanity in, it would bomb. You wrote a character who was totally brutal and totally ruthless, the readers would love it. John Wagner and I had both observed this trend in reader taste, so what you might call a traditional hero just didn't cut it." He happily found that the nature of the new comic gave him something of a get-out from higher-ups' disapproval: the sci-fi backdrops served to make the violence and harsh ambience seem less 'real'. An indication of just how much thought went into 2000 AD is Mills's work on the comic's look. He admired the high standards of Spaniards like Carlos Ezquerra and Italians like Massimo Belardinelli. However, though he commissioned Continental artists, he also felt them to be a little dull compared to technically inferior British ones. -

Portland Daily Press : May 21,1868

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. Established June 23,1H62. lot. 7. THURSDAY MAY PORTLAND, MORNING, 21, 1868 Terms $8.00 per annum, in ad ranee. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS BUSINESS tapublished CARDS. M N KOIIS. Jlny Traiaiug L> IM,W ear. Ko. 1 PrlnteMr MISCELLANEOUS. __WANTED fSOELLA l>...ap-liirr. £W*T day, (Huuday pled.) at ___ Exchange, Exchange Street, Portland. DAILY PRESS. Doveu, N. H„ May 18, 1868. N. A. PsoraiEl<>*• FIRST CLASS FOSTER, J. o. LOVE JOY, No, 5. To the Editor of the Press: I Kitua:—Eight Dollar* a year in advance. Wholesale CoMDiinsiuu Dealer la PORTLAND. May training came off here last week. The MT Single copic* I ceuta. SIMILIA 8IMIL1BUS CUBANTDR. day was and and more Cook Wanted l I glorious everybody too la at the IMPEACHMENT THE MAINE STATE PRESS, puMiabed Cement and was out to witness the exercises. Dover has aatue morning at $2.00 a year, Lime, Plaster, a 21,1868. place every Tbnraday private family. C od wages will bo paiil to Thursday Morning, May three u vat u van* «*. companiesuin all the of war My in a*I !I!{ Coinmcreinl St., and Furniture Gone Doivn I INolio wi 11 recommended. Humphrey’s Homceopathic Specifics, panoply Gone Up, to and Apply from the most arrayed” this year was ex- Rati h or Advert kino.—One in* li ot in PROVED, ample experi- The l.ntc May training *|«ce, ... MAINE Npring. PORTLAND, * STEWARD OF UNION CLUB. HAVEence, si?i entire success; Effi- to be length ot column, comtiiutcaa “aquare.*' HAVING A LARGE STOCK OF 19 till Simple—Prompt- pected unusually well observed. -

Look and Learn a History of the Classic Children's Magazine By

Look and Learn A History of the Classic Children's Magazine By Steve Holland Text © Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 2006 First published 2006 in PDF form on www.lookandlearn.com by Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 54 Upper Montagu Street, London W1H 1SL 1 Acknowledgments Compiling the history of Look and Learn would have be an impossible task had it not been for the considerable help and assistance of many people, some directly involved in the magazine itself, some lifetime fans of the magazine and its creators. I am extremely grateful to them all for allowing me to draw on their memories to piece together the complex and entertaining story of the various papers covered in this book. First and foremost I must thank the former staff members of Look and Learn and Fleetway Publications (later IPC Magazines) for making themselves available for long and often rambling interviews, including Bob Bartholomew, Keith Chapman, Doug Church, Philip Gorton, Sue Lamb, Stan Macdonald, Leonard Matthews, Roy MacAdorey, Maggie Meade-King, John Melhuish, Mike Moorcock, Gil Page, Colin Parker, Jack Parker, Frank S. Pepper, Noreen Pleavin, John Sanders and Jim Storrie. My thanks also to Oliver Frey, Wilf Hardy, Wendy Meadway, Roger Payne and Clive Uptton, for detailing their artistic exploits on the magazine. Jenny Marlowe, Ronan Morgan, June Vincent and Beryl Vuolo also deserve thanks for their help filling in details that would otherwise have escaped me. David Abbott and Paul Philips, both of IPC Media, Susan Gardner of the Guild of Aviation Artists and Morva White of The Bible Society were all helpful in locating information and contacts. -

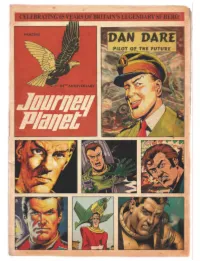

Journey Planet 24 - June 2015 James Bacon ~ Michael Carroll ~ Chris Garcia Great Newseditors Chums! The

I I • • • 1 JOURNEY PLANET 24 - JUNE 2015 JAMES BACON ~ MICHAEL CARROLL ~ CHRIS GARCIA GREAT NEWSEDITORS CHUMS! THE Dan Dare and related characters are (C) the Dan Dare Corporation. All other illustrations and photographs are (C) their original creators. Table of Contents Page 3 - Some Years in the Future - An Editorial by Michael Carroll Dan Dare in Print Page 6 - The Rise and Fall of Frank Hampson: A Personal View by Edward James Page 9 - The Crisis of Multiple Dares by David MacDonald Page 11 - A Whole New Universe to Master! - Michael Carroll looks back at the 2000AD incarnation of Dan Dare Page 15 - Virgin Comics’ Dan Dare by Gary Eskine Page 17 - Bryan Talbot Interviewed by James Bacon Page 19 - Making the Old New Again by Dave Hendrick Page 21 - 65 Years of Dan Dare by Barrie Tomlinson Page 23 - John Higgins on Dan Dare Page 26 - Richard Bruton on Dan Dare Page 28 - Truth or Dare by Peppard Saltine Page 31 - The Bidding War for the 1963 Dan Dare Annual by Steve Winders Page 33 - Dan Dare: My Part in His Revival by Pat Mills Page 36 -Great News Chums! The Eagle Family Tree by Jeremy Briggs Dan Dare is Everywhere! Page 39 - Dan Dare badge from Bill Burns Page 40 - My Brother the Mekon and Other Thrilling Space Stories by Helena Nash Page 45 - Dan Dare on the Wireless by Steve Winders Page 50 - Lego Dan Dare by James Shields Page 51 - The Spacefleet Project by Dr. Raymond D. Wright Page 54 - Through a Glass Darely: Ministry of Space by Helena Nash Page 59 - Dan Dare: The Video Game by James Shields Page 61 - Dan Dare vs. -

Comics and Graphic Novels Cambridge History of The

Comics and Graphic Novels Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 7: the Twentieth Century and Beyond Mark Nixon Comics – the telling of stories by means of a sequence of pictures and, usually, words – were born in Britain in the late nineteenth century, with Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday (Gilbert Dalziel, 1884) and subsequent imitators. These publications were a few pages long, unbound, and cheap – and intended for working-class adult readers. During the twentieth century, bound books of picture stories developed in Europe and North America, and by the end of the century had become a significant factor in British publishing and popular culture. However, British comics scholarship has been slow to develop, at least relative to continental European and North American comics scholarship, although specialist magazines such as The Comics Journal, Comics International and Book & Magazine Collector have featured articles on British comics, their publishers and creators. Towards the end of the twentieth century, the work of Martin Barker and Roger Sabin began to shed new light on certain aspects of the history of British comics, a baton now being taken up by a few scholars of British popular culture1, alongside a growing popular literature on British comics2. 1 For a recent overview, see Chapman, James British comics: a cultural history (London, 2011). 2 Perhaps the best example of this is Gravett, Paul and Stanbury, Peter Great British comics (London, 2006). By the beginning of the twentieth century, Harmsworth dominated the comics market they had entered in 1890 with Comic Cuts and Illustrated Chips. Their comics provided the template for the industry, of eight-page, tabloid-sized publications with a mixture of one-panel cartoons, picture strips and text stories, selling at 1/2d. -

Clive Collins Cartoons Giles Council of War!

ISSUE 413 – SEPTEMBER 2008 TheThe Jester Jester LATE SUMMER BRRR! BIT NIPPY TIME FOR A BARBECUE ISSUE Bill Ritchie CUTTINGS DACS SAY DRAW EVENTS DIARY GALORE YOUR RIGHTS UPDATE SIZZLING BBQ IN PRAISE OF CLIVE COLLINS CARTOONS GILES COUNCIL OF WAR! TheNewsletter Newsletter of of the the Cartoonists’ Cartoonists’ Club Club of Greatof Great Britain Britain THE JESTER ISSUE 413 – SEPTEMBER 2008 CCGB ONLINE: WWW.CCGB.ORG.UK The Jester The CCGB Committee The Chair Issue 413 - September 2008 Published 11 times a year by The Cartoonists! Club Dear Members, of Great Britain Please can you do a swift car- Chairman: Terry Christien Well what about the Olympics? I toon depicting what these rights 020-8892 3621 and 'er indoors have been com- pletely absorbed not only by the mean to you and send it/them to [email protected] sheer brilliance of the competi- Artist's Resale Right as per the Secretary: Jed Stone tors but the excellence of the write up on page ....BY 22nd 01173 169 277 glossy TV coverage. I know it's SEPTEMBER - a big big thank [email protected] easy to be cynical about the you! Treasurer: Anne Boyd whole thing but if you've done Meanwhile, Pete Dredge is get- 01173 169 277 some sport in your own modest ting as many of you together as [email protected] way over the years, you've got to poss for a regional meeting on Membership Secretary: appreciate the whole mighty the 13th September in Notting- Jed Pascoe: 01767-682 882 individual effort. -

Eagle Comic Vehicle Cutaways from Road Building to Warfare

© Mumfordebooks.com Knowledge at the speed of Light Eagle Comic Vehicle Cutaways from Road Building to Warfare Copyright MumfordBooks-Guides 2020 1 © Mumfordebooks.com Knowledge at the speed of Light Eagle Comic Vehicle Cutaways 20 matched double centers Visual Aids Educational Series PublishedCopyright by ©MumfordBooks-Guides Mumfordebooks.com 2020 2020 27 The Cloisters Rhos-on-Sea Colwyn Bay Conwy LL28 4PW This edition is published as an eBook PDF FREE Download Suitable for helping to teach industrial history by illustrations, ideal for special needs help in reading text using GOOGLE Translate with a choice of over hundred languages. Publisher & Editor Michael Robert Mumford Original All Eagle material © Dan Dare Corporation - Colin Frewin We claim Fair Use for study, research, education & special needs. Fully compliant with the Copyright Act 2 © Mumfordebooks.com Knowledge at the speed of Light INTRODUCTION Mumfordbooks Vehicle Cutaway Illustrated: A selection of matched and paired Eagle Centres showing vehicle history from the pioneers to the late sixties. Examples of vehicles range from private, commercial to military. This wide range of vehicles include experimental to mass produced. Each download is great value, yours for FREE. Each download can be printed to A4 size, not big enough to read all the original text and technical fine detail. The first issue of Eagle Comic’s was released in April 1950. Revolutionary in its presentation and content, it was enormously successful, the first issue sold about 900,000 copies. Featured in colour on the front cover was its most recognisable story, Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, created by Hampson with meticulous attention to detail.