Towards Equality: Priority Issues of Concern for Women in Policing in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Police Officers in Assam As on 21-06-2019

LIST OF POLICE OFFICERS IN ASSAM AS ON 21-06-2019 SL Name & Rank Of Officers No. STD Office Fax Mobile No. E-mail ID Assam Police Hqrs. Shri Kuladhar Saikia IPS 2450555 2525397 1 0361 9435049624 [email protected] DGP, Assam 2455126 2524028 Shri B.K. Mishra IPS 2 0361 2468515 9435197333 ADGP(OSD), Assam Shri Mukesh Agrawal IPS 3 0361 2456971 2737711 9435048633 [email protected] ADGP(L&O), Assam Shri Harmeet Singh IPS [email protected] 4 0361 2524383 9958579797 ADGP(Admn /Security / M&L /V&AC), Assam [email protected] Shri Y.K. Gautam, IPS 9435522477 5 ADGP( Prosecution / Addl. Charge ADGP STF), 0361 2468515 [email protected] 9654958804 Assam 6 IGP(Admn.), Assam 0361 2526077 [email protected] Shri Deepak Kr. Kedia IPS 7 0361 2526601 9868156325 [email protected] IGP(L&O), Assam Shri Anurag Tankha IPS 8 IGP(V&AC/Addl. Charge IGP (MPC)/CM's SVC, 0361 8468832675 [email protected] Assam Shri Diganta Barah IPS 9 0361 2521703 9678009954 [email protected] DIGP(Admn.), Assam Shri Nitul Gogoi IPS 10 0361 2453308 9435028701 DIGP (MPC), Assam Shri Arabinda Kalita IPS 11 0361 2467696 9435041253 DIGP (L&O), Assam Shri Rafiul Alam Laskar, IPS 12 0361 8811078433 [email protected] AIGP(Admn.), Assam Shri Krishna Das APS 13 0361 2523143 9435734233 [email protected] AIGP (Law & Order), Assam Shri Mahesh Chand Sharmah APS 14 0361 2460930 9435025666 AIGP(W&S), Assam. -

(PPMG) Police Medal for Gallantry (PMG) President's

Force Wise/State Wise list of Medal awardees to the Police Personnel on the occasion of Republic Day 2020 Si. Name of States/ President's Police Medal President's Police Medal No. Organization Police Medal for Gallantry Police Medal (PM) for for Gallantry (PMG) (PPM) for Meritorious (PPMG) Distinguished Service Service 1 Andhra Pradesh 00 00 02 15 2 Arunachal Pradesh 00 00 01 02 3 Assam 00 00 01 12 4 Bihar 00 07 03 10 5 Chhattisgarh 00 08 01 09 6 Delhi 00 12 02 17 7 Goa 00 00 01 01 8 Gujarat 00 00 02 17 9 Haryana 00 00 02 12 10 Himachal Pradesh 00 00 01 04 11 Jammu & Kashmir 03 105 02 16 12 Jharkhand 00 33 01 12 13 Karnataka 00 00 00 19 14 Kerala 00 00 00 10 15 Madhya Pradesh 00 00 04 17 16 Maharashtra 00 10 04 40 17 Manipur 00 02 01 07 18 Meghalaya 00 00 01 02 19 Mizoram 00 00 01 03 20 Nagaland 00 00 01 03 21 Odisha 00 16 02 11 22 Punjab 00 04 02 16 23 Rajasthan 00 00 02 16 24 Sikkim 00 00 00 01 25 Tamil Nadu 00 00 03 21 26 Telangana 00 00 01 12 27 Tripura 00 00 01 06 28 Uttar Pradesh 00 00 06 72 29 Uttarakhand 00 00 01 06 30 West Bengal 00 00 02 20 UTs 31 Andaman & 00 00 00 03 Nicobar Islands 32 Chandigarh 00 00 00 01 33 Dadra & Nagar 00 00 00 01 Haveli 34 Daman & Diu 00 00 00 00 02 35 Puducherry 00 00 00 CAPFs/Other Organizations 13 36 Assam Rifles 00 00 01 46 37 BSF 00 09 05 24 38 CISF 00 00 03 39 CRPF 01 75 06 56 12 40 ITBP 00 00 03 04 41 NSG 00 00 00 11 42 SSB 00 04 03 21 43 CBI 00 00 07 44 IB (MHA) 00 00 08 23 04 45 SPG 00 00 01 02 46 BPR&D 00 01 47 NCRB 00 00 00 04 48 NIA 00 00 01 01 49 SPV NPA 01 04 50 NDRF 00 00 00 00 51 LNJN NICFS 00 00 00 00 52 MHA proper 00 00 01 15 53 M/o Railways 00 01 02 (RPF) Total 04 286 93 657 LIST OF AWARDEES OF PRESIDENT'S POLICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY ON THE OCCASION OF REPUBLIC DAY-2020 President's Police Medal for Gallantry (PPMG) JAMMU & KASHMIR S/SHRI Sl No Name Rank Medal Awarded 1 Abdul Jabbar, IPS SSP PPMG 2 Gh. -

Life Expectancy of Police Personnel of the 6 Th Assam Police Battalion

Life Expectancy of Police Personnel of the 6th Assam Police Battalion, Kathal, Cachar District, Assam: A Report Data Source: Service particulars of Expired and Retired Personnel of the 6th Assam Police Battalion, Kathal, Silchar as supplied by the concerned office. Prepared by: Dibyojyoti Bhattacharjee, Professor and Head, Department of Statistics, Assam University, Silchar February, 2020 1 Introduction Life expectancy is an estimate of the average number of additional years that a person of a given age shall live. The most common measure of life expectancy is life expectancy at birth. Life expectancy at birth is the average number of years that a person is expected to survive. As per the World Bank data of 2016 Japan has the highest Life expectancy at birth i.e. 83.98 years. This means that a child born in Japan (in 2016) is expected to survive to an age of almost 84 years on an average. The same value is 82.3 in Canada and 80.9 in the United Kingdom. Life expectancy at birth in the same report is 78.7 in the United States, 76.3 in China and in India it is as low as 68.6. Life expectancy at birth is a crude measure of the prevailing health condition of a country. The above statistics indicated that roughly speaking India requires improvement in her health infrastructure as it is way behind other leading countries of the world in terms of life expectancy at birth. However, life expectancy differs considerably by sex, age, race, profession and geographical location. Therefore, life expectancy is commonly given for specific categories, rather than for the population in general. -

Community Policing in North Eastern India: Benefits, Challenges and Action Plan for Better Policing to Achieve Access to Justice”

ACCESS TO JUSTICE PROJECT IN NORTH EASTERN STATES & JAMMU & KASHMIR MINUTES OF CONFERENCE ON “Community Policing in North Eastern India: Benefits, Challenges and Action Plan for Better Policing to Achieve Access to Justice” JULY 31ST, 2016 ORGANISED BY: DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, MINISTRY OF LAW AND JUSTICE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA INTRODUCTION The rule of law and access to justice are fundamental to ensuring the human rights. In spite of its central status in achieving development and equality, there are several marginalized groups of people who are not able to seek remedies from the justice system. Therefore, it is necessary to take concrete action geared towards addressing these challenges effectively. Productive convergence and collaborations among the Legal Service Authorities, Government, Civil Society Organizations and Law Universities are required to strengthen access to justice concerns. With the aim of achieving these goals, the Department of Justice (DoJ), Government of India initiated a project on “Access to Justice in North Eastern States and Jammu and Kashmir” under 12th Five Year Plan. The project seeks to address the needs of poor and vulnerable persons. It mainly focuses on supporting justice delivery systems by improving their capacities to serve the people and in empowering the ordinary people to access their rights and entitlements. Under this project, inter alia, a Needs Assessment Study to Identify Gaps in the Legal Empowerment of People in North Eastern States was undertaken which recommended the need to work on the issue of community policing. Also the Standing Finance Committee of the project suggested community policing as one of the priority area. -

CISF Unit VSP Vizag, Vizag [email protected] Steel Plant,Vishakapatnam, Andhra Pradesh

DETAIL OF MASTER CANTEENS ZONES STATE MASTER CANTEEN E-mail SOUTH ANDHRA PRADESH 1 CISF Unit VSP Vizag, Vizag [email protected] Steel Plant,Vishakapatnam, Andhra Pradesh SOUTH TELANGANA 2 CISF NISA Complex [email protected] Hyderabad, PO-Hakimpet, Andhra Pradesh SOUTH TELANGANA 3 GC, CRPF, Rengareddy Post- [email protected] Nisha, Hakimpet, JJ Nagar,Distt- m RRY (AP) SOUTH ANDMAN & NIKOBAR 4 Joint Secretary CPC, Andman [email protected] Nikobar Police Port Blair, Island PO-Shadipur, Pin-744 106 EAST ARUNACHAL 5 NE FTR HQ, ITBP, Khating Hill, [email protected] PRADESH near Radio Stn. Distt- Papumpare, Itanagar (Arunachal Pradesh)- 791 111 EAST ASSAM 6 FTR HQ BSF, [email protected] Guwahati,Patgaon, PO-Azahar, Dist-Kamrup, Guwahati (Assam) EAST ASSAM 7 SHQ BSF, Silchar, PO- [email protected] Arunchal, Distt. Cachar (Assam) EAST ASSAM 8 GC, CRPF, Guwahati, 9th Mile [email protected], Amerigog, Guwahati-23 [email protected] EAST ASSAM 9 GC, CRPF, Silchar Dayapur, [email protected] Silchar, (Assam) EAST ASSAM 10 FTR HQ SSB, Guwahati, Block- [email protected] B-8, Flat No.001, Games Village Post Office Veltola, Guwahati, Dist- Kamrup (Assam)-781029 EAST ASSAM 11 GC CRPF, Khatkhati, PO- [email protected] Dimapur, Nagaland, 797112 CENTRAL BIHAR 12 SHQ, BSF, Kishanganj, Khagra [email protected] Camp, PO & Dist:Kishanganj, Bihar CENTRAL BIHAR 13 CISF Unit KhSTPP Kahalgaon, [email protected], P.O: Deeptinagar, Distt. Bhagalpur, Bihar-813214 CENTRAL BIHAR 14 GC, CRPF, Mokamaghat, -

Page 01 June 09.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Sunday 9 June 2013 30 Rajab 1434 - Volume 18 Number 5725 Price: QR2 QIB signs $100m In-form Serena Murabaha facility clinches French with QFB Open title in Paris Business | 17 Sport | 28 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Stormy weather to continue PSG president Souq Haraj not allowing coach to leave, to soon face say reports DOHA: Qatar-owned Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) will not allow coach Carlo Ancelotti to leave until a replacement bulldozers is found, the club’s president, Nasser Al Khelaifi, said accord- ing to French news reports. Commercial complex planned Ancelotti, who guided the French giants to their first league DOHA: The historic Souq country in preparation for the title since 1994 in May, last month Haraj — Qatar’s only market for coveted FIFA World Cup 2022. confirmed his intention to join used goods and a major land- Sheikh Faisal said the shops Spain’s Real Madrid, who have mark — might soon face the in Souq Haraj will be shifted to recently parted ways with Jose bulldozers to give way to a huge another location. He didn’t, how- Mourinho. and posh commercial avenue ever, give details. After various news reports which is also expected to boast Souq Haraj is an old market appeared in the French and a twin-hotel complex. that now also houses an array of Spanish media over the Italian Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim shops selling first-hand goods. It Waves generated by strong winds lash the shore at the Corniche in Doha yesterday. -

Particulars of Organization, Functions and Duties 2.1. Objective/Purpose

Chapter-2 (Manual 1) Particulars of Organization, Functions and Duties 2.1. Objective/purpose of the public authority. * Provide an honest efficient, effective, law abiding, courteous, responsive and a professionally competent law enforcement machinery. * Protect lives and properties of people from criminals and anti social elements. * Maintain law and order in society by taking all possible measures to prevent breach of peace and in case breach of peace takes place, to bring the situation back to normal with utmost speed. * Strict enforcement of legal provisions with regard to human rights. * Earn goodwill, support and active assistance of the community. * Equal treatment to all irrespective of religion, caste, social, economic status and political affiliation. * Effective prevention and detection of crime. * Effective management of traffic. * Take firm and prompt action against the anti-social and rowdy elements. * Maintain public order during fairs, festivals, public functions, processions, strikes, agitations, etc. 2.2. Mission / Vision Statement of the public authority. Our goal is to prevent crime, maintain public order, uphold justice, ensure the Rule and Law, and have honesty, integrity and fairness in all our dealings. We are committed to the safety and security of all our citizens in partnership with the people. 2.3. Brief history of the public authority and context of its formation. The history of Meghalaya Police is intrinsically linked with the origin, growth and evolution of Assam Police before 1972, the year Meghalaya was born having been carved out of the existing territory of Assam. The creation of Meghalaya as a state is also considered as the beginning of Meghalaya Police. -

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JANUARY 2, 1925. James Tuck, Constable, City of London Police, "William John Brooking, Constable, Co

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JANUARY 2, 1925. James Tuck, Constable, City of London Police, H G Lang, Superintendent, "William John Brooking, Constable, Cornwall Agency Police, Kathiawar. Constabulary. Hari Narayan Pimple, Temporary Deputy Albert Thomas, Constable, Salford Borough Superintendent, Bombay Police. Police. Syeduddin Ahmad, Sub-Inspector, Bengal George Fisher, Constable, Metropolitan Police. Police.' Eobert Harding, Constable, Metropolitan Satish Chandra Chakrabatti, Officiating Sub- Police. Inspector, Calcutta Police Harold Peckover, Constable, Metropolitan Shiekh Abdul Karim, Constable, Calcutta Police. Police. Percival Norman, Constable L Metropolitan Muhammad Syed Ali, Sub-Inspector, Bengal Police. Police. Harold Vincent, Constable, Metropolitan Percival Clifford Bamford, Superintender.i., Police. Bengal Police. FIRE BRIGADE. Arthur Durham Ashdown, Officiating Inspector General, United Provinces Police. Henry Neal, Chief Officer, Leicester Fire Munir Hussain, Head Constable, United Brigade. Provinces Police. SCOTLAND. Ali Mirza, Sub-Inspector, United Provinces John Carmichael, Chief Constable, Dundee Police. City Police. Narayan Singh, Head Constable, United Hugh Calder, Superintendent, Edinburgh City Provinces Police. Police. Brahma Narayan Awasthi, Sub-Inspector, James Ferguson, Superintendent, Glasgow United Provinces Police. City Police. William Norman Prentrice Jenkin, Assistant John Campbell, Sergeant, Boss and Cromarty Superintendent, United Provinces Police. Constabulary. Agha Ahmad Said, Inspector, Punjab Police. John -

Assam Police: a Historical Overview

ASSAM POLICE: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW NIRMALEE KAKATI Research Scholar Department Of Political Science Gauhati University, Assam (INDIA) During the time of the Ahom kings, policing did not exist in Assam. Army and various officers of the kingdom were responsible for maintenance of peace. The Police in Assam is the result of continuous process of development since the Britishers occupied Assam in 1826. After taking over the administration of Assam, no such revolutionary changes are taken by Britishers in this respect and they employed army for maintaining law and order. They also set up army outposts at different places. There was the involvement of high expenditure in maintaining a large body of troops and that was at a time when the country had just settled down. This compelled the government of the time to undertake a review of the situation and a policy of gradual reduction of the forces was adopted. By 1839-40 the number of troops was reduced to only four regiments in Assam. They also took various steps to increase the armed component of the Civil Police in the province. There was also the necessity of raising a separate force under the civil government apart from the armed civil Police and the first unit of this new organisation was formed in1835 by one Mr. Grange, the Head of the civil administration of Nowgong District at that time. Before the coming of Britishers, police force was not a separate organisation entrusted with specific functions. The British created police organisation to serve its colonial interests, and therefore, its loyalty was towards the British Government. -

Rhinos, Trade and CITES : a Joint Report by IUCN SSC African and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and TRAFFIC to CITES Secretaria

African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade A report from the IUCN Species Survival Commission (IUCN SSC) African and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and TRAFFIC to the CITES Secretariat pursuant to Resolution Conf. 9.14 (Rev. CoP15) Richard H Emslie1,2 , Tom Milliken 3,1 Bibhab Talukdar 2,1 Susie Ellis 2,1, Keryn Adcock1, and Michael H Knight1 (compilers) 1 IUCN SSC African Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG) 2 IUCN SSC Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG) 3 TRAFFIC 1. Introduction The CITES Parties, through Resolution Conf 9.14 (Rev. CoP15), have mandated IUCN SSC’s African Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG), Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG) and TRAFFIC to prepare a comprehensive report for the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP17) on the conservation status of African and Asian rhinoceros species, trade in specimens, stocks and stock management, illegal killing, enforcement issues, conservation actions and management strategies and measures by implicated States to end illegal use and consumption of rhino parts and derivatives. This report primarily deals with developments since CoP16. 2. African Rhinos 2.1 Status and trends Table 1: Estimated numbers of African rhino species by country in 2015 with revised totals for 2012* (AfRSG data in collaboration with range States). White Rhino Black Rhino Both Both Species Species Ceratotherium simum Diceros bicornis Estimates as Total Total % of Southern- South- Total of 31 Dec Southern Northern White & Eastern Black & Continental central western 2015 2015 Trend -

Assam Police Manual Part II Office of the Superintendent of Police Ministerial Establishment

Assam Police Manual Part II Office of the Superintendent of Police Ministerial Establishment (Rules 1 to 18) 1. Ministerial establishment ................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Pay ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 3. Appointments and qualifications of head assistants and accountants ................................................................ 7 4. Appointments and qualifications of subordinate assistants ............................................................................... 7 5. General orders in regard to ministerial appointments ........................................................................................ 7 6. Leave of ministerial officers .............................................................................................................................. 9 7. Vacancies and promotions ............................................................................................................................... 10 8. Renewal of temporary establishment ............................................................................................................... 10 9. Permanent vacancies to be advertised .............................................................................................................. 10 10. Periodical transfer of head assistants and accountants -

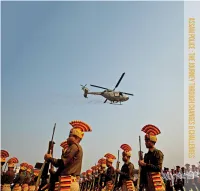

ASSAM POLICE: the JOURNEY THROUGH CHANGES & CHALLENGES (Part 1)

ASSAM POLICE the journey through changes & challenges ASSAM POLICE the journey through changes & challenges Edited by Samudra Gupta Kashyap Bijay Sankar Bora on inputs provided by Assam Police Photographs Anupam Nath Assam Police Publisher: Assam Police First Published: 2019 Layout & Design Himangshu Lahkar No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil clams for damage. Copyright Assam Police Printed at: Bhabani Offset & Imaging Systems Pvt. Ltd. Sarbananda Sonowal Chief Minister, Assam Guwahati Dispur 09.08.2019 MESSAGE Assam Police personnel always render their duty displaying the highest order of integrity and discipline in accordance with the law and the Constitution and respect the rights of citizens as guaranteed by it. It is really heartening to know that the Assam Police is bringing out a book to give a pictorial representation of some of its unlimited selfl ess demeanours that it undertakes during peace or disturbed situation apart from its humanitarian works that it occasionally does for the welfare of all. Hope the book brings to light the onerous task undertaken by the Assam Police in saving lives and properties of our people and ensuring enduring smile to our citizens. I am sure that the book would be well appreciated by all. (SARBANANDA(SARBANANDA SONOWAL)SONOWAL FOREWORD ince the compilation of the book ‘Assam Police through the Years’, there have been lot of changes in the Assam Police at the organizational, structural and multiple other strategic Slevels in this decade-long hiatus.