Inspector's Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

The Swansea Branch Chronicle 9

Issue 9 Summer 2015 The 18th century Georgians Contents Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in fetters. Jean-Jaques Rousseau 1762 3 From the Editor 4 From the Chairman 5 Hymn Writer Supreme Dr R. Brinley Jones 6 Venice, the Biennale and Wales Dr John Law 7 18th Century Underwear Sweet disorder in her dress, kindles in Jean Webber Clothes a wantonness. 9 Whigs and wigs Robert Herrick 12 Howell Harris David James 15 Branch news 16 British Government’s Response to French Revolution Elizabeth Sparrow 18 Reviews 20 Joseph Tregellis Price Jeffrey L Griffiths Oil painting by Nicolas Largilliere 22 School’s Essay Competition Richard Lewis 24 Programme of Events Madame de Pompadour From the Editor Margaret McCloy The 18th century what a great time to live in London… that is, if you were wealthy and a gentleman. Mornings could be spent in the fashionable new coffee bars talking to the intelligentsia discussing the new whether a new Gothic tale by Horace Walpole, The architectural studies by William Kent, based on Italian Times or Dr Johnson’s, A Dictionary of the English Palladian houses,seen by Lord Burlington. In Italy. Or Language. Quite a few hours of reading. marvel at Sheraton’s latest designs in elegant Evenings were for dining and listening to music, furniture. Maybe make a trip to New Bond Street and perhaps the latest works from Mozart and Haydn.With enjoy an afternoon drink in the King’s Arms discussing luck, you may be invited to Handel’s house in Brook the theatre in the company of artists and actors. -

CONFERENCE VENUE Swansea University Wallace Building

CONFERENCE VENUE Swansea University Wallace Building The Wallace Building, Swansea University The conference venue for the UKIRSC 2019 is the Wallace Building on Singleton Campus, Swansea University, SA2 8PP. The Wallace Building is home to the Bioscience and Geography departments and is named after the “father of biogeography”, Alfred Russel Wallace, Welsh evolutionary biologist best known for having independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection, alongside Charles Darwin. Swansea University is situated in Singleton Park, a mature parkland and botanical gardens overlooking Swansea Bay beach. The Wallace Building is in the South West corner of Singleton Campus. It is approximately 15 minutes’ walk from the Uplands or Brynmill areas, 40 minutes’ walk from Swansea City Centre and 3 minutes from the beach (see map on page 5). 1 Registration will be held in the entrance foyer of the Wallace building. From there you can head directly upstairs to the Science Central for refreshments. Scientific posters will be displayed here. All guest lectures and student talks will take place in the Wallace Lecture Theatre, directly ahead on entering the Wallace Building and located down a short flight of stairs. Tea and coffee will be provided on arrival and during breaks, but please bring your own re-usable cup. Lunch is not provided. There are plenty of options for lunch on campus and in the Uplands and Brynmill area just short walk away. The Wallace Building Foyer. Down the stairs and ahead to the Wallace Lecture Theatre or up the stairs to Science Central. 2 ACCOMODATION Staying with Students There should be a limited number of beds/sofas available with students based in Swansea. -

35 Trafalgar Place, Brynmill

Property details 35 Trafalgar Place, Brynmill. Swansea. SA2 0DA £360 per calendar month per person Description This 5 bedroom student house has a great location in the middle of Brynmill less than 15 minutes’ walk away from Swansea University. It is fully furnished, has 5 large bedrooms and 1 single, an open plan kitchen and dining area and a separate living room. It has recently been fitted with new carpets. It has 2 bathrooms including 2 showers. It was recently re-carpeted and it has been painted throughout. Wi-Fi is available thought students are expected to make their own arrangements for an ISP. Street parking is available with a permit. Features • Fully furnished • Wi-Fi • 5 double bedrooms • Washing machine • 1 kitchens • Fridge/freezer • 2 bathrooms • Full maintenance and administrative • 2 showers support • Gas central heating Location Brynmill is the main student area in the city. This property is part of a small square close to the local primary school and is no more than a few minutes’ walk from local shops and amenities, including the well-known Rhyddings Hotel. You have a choice of good shopping in easy walking distance, either in the busy Brynymor Road and St Helens Road area, where you can find a mixture of restaurants, take-aways, pubs and convenience stores, or in Uplands which offers you Tesco and Sainsbury's and another mix of places to eat and drink. The sea front of Swansea Bay is a short walk from the house. There is a bus stop in nearby Marlborough Road for the no. -

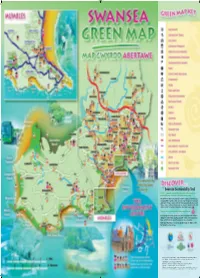

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

PG Prospectus 2019

swansea.ac.uk/postgraduate 2019 POSTGRADUATE Swansea University I believe that collaboration is the key to change. Dr Lella Nouri, Senior Lecturer – Criminology POSTGRADUATE 2019 SwanseaPostgrad SwanseaPostgrad Swansea Uni #SwanseaUni UK UK OPEN DAYS TOP 10 TEACHING TOP 30 BEST UNIVERSITY EXCELLENCE RESEARCH EXCELLENCE 7 November 2018 6 March 2019 (WhatUni Student Choice Awards 2018) (QS Stars global university ratings system 2017) (Research Excellence Framework 2014-2021) (Singleton Park Campus) (Singleton Park Campus) 14 November 2018 13 March 2019 UK (Bay Campus) (Bay Campus) 3RD TOP 10 MOST AFFORDABLE GREENEST UNIVERSITY UK UNIVERSITY TOWN Swansea University £89 average weekly rent (Guardian People & Planet University League 2017) (totallymoney.com 2018) LOOK WHO’S MAKING WAVES AT SWANSEA UNIVERSITY... DR LELLA NOURI ALEX RUDDY ELINOR MELOY A pioneer in cyberterrorism research Trainee doctor with fighting spirit Ecologist who wants to Page 20 Page 30 change the world Page 40 SwanseaPostgrad swanseauni Swansea Uni swanseauni swanseauni WELCOME FROM OUR VICE-CHANCELLOR Swansea University has been at the This is an exciting time to join us. We have cutting edge of research and innovation invested over £750 million in our facilities since 1920. to provide you with the best environment in which to conduct your research. As a We have a long history of working with postgraduate student, you will be a valued business and industry but today our world member of our academic community with class research has a much wider impact access to the expertise of research staff, across the health, wealth, culture, and many of whom are world renowned leaders well-being of our society. -

The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Half

THE GLAMORGAN-GWENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST TRACK 1 0 0 . 9 5 7 9 9 0 . 9 m 5 9 9 9 9 . 0 . 5 8 8 7 0 m 0 . 0 5 0 m 0 0 0 m 0 m m m Area of rock outcrop T R A 10 C 0.0 K 0m 9 6 .5 0 m 100.00m 9 9.5 0m 9 6 . 9 0 9 8. 9. 0 50 00 m m m G R Chamber A Chamber B ID N 0 30metres Plan of Graig Fawr chambered tomb showing chambers A and B, and the possible extent of the cairn area (shaded) HALF-YEARLY REVIEW 2007 & ANNUAL REVIEW OF PROJECTS 2006-2007 ISTER G E E D R GLAMORGAN GWENT IFA O ARCHAEOLOGICAL R N G O TRUST LTD I A T N A I S RAO No15 REVIEW OF CADW PROJECTS APRIL 2006 — MARCH 2007 ................................................... 2 GGAT 1 Heritage Management ....................................................................................................... 2 GGAT 43 Regional Archaeological Planning Services .................................................................... 9 GGAT 61 Historic Landscape Characterisation: Gower Historic Landscape Website Work. ........ 11 GGAT 67 Tir Gofal......................................................................................................................... 12 GGAT 72 Prehistoric Funerary and Ritual Sites ............................................................................ 12 GGAT 75 Roman Vici and Roads.................................................................................................. 14 GGAT 78 Prehistoric Defended Enclosures .................................................................................. 14 GGAT 80 Southeast Wales Ironworks.......................................................................................... -

Swansea Walk

bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2013 Weatherman Walking Swansea Walk Approximate distance: 3.7 miles For this walk we’ve included OS grid references should you wish to use them. Start 5 2 1 3 End 4 N W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to help you walk the route. We recommend using an OS map of the area in conjunction with this guide. Routes and conditions may have changed since this guide was written. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check 1 weather conditions before heading out. bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2013 Weatherman Walking Swansea Walk Start: Directly outside the house where Dylan Thomas was born, 5 Cwmdonkin Drive Starting ref: SS 6406 932 Distance: About 3.7 miles Grade: Easy/Moderate Walk time : Allow 1.5 hours Starting at Dylan’s old home on Cwmdonkin Drive in the Uplands area of Swansea, this walk will take you through three beautiful parks before reaching Swansea Bay. You will then take a short stroll along the Wales Coast Path, meeting the famous Swansea Jack on the way. The route then takes you to the city centre and around Castle Square, before dropping back down to the Maritime Quarter to end with a drink in one of Dylan’s infamous watering holes. 1 Dylan’s Home (SS 6406 932) Dylan Thomas’s parents moved to the newly-built 5 Cwmdonkin Drive in 1914 and Dylan was born here on October 27th of that year. -

Road Closure Notice

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA CYNGOR DINAS A SIR ABERTAWE TEMPORARY RESTRICTIONS/ROAD CLOSURES 2017 WALES NATIONAL AIRSHOW NOTICE 2017 The Council of the City and County of Swansea in exercise of the powers conferred by Section 21 of the Town Police Clauses Act 1847 HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that on Friday 30th June, Saturday 1st and Sunday 2nd July 2017, as and when the appropriate traffic signs are displayed no person shall cause a vehicle (other than a vehicle being used for emergency purposes) to proceed along the length or lengths of road(s) referred to in the Schedule below. SCHEDULE No Access -12:00hrs Friday 30th June to 07:00hrs Monday 3rd July No access for vehicular traffic into A4067 Oystermouth Road from the following roads; Gorse Lane Guildhall Road South St Helens Road Bond Street Beach Street St Gabriels Walk Roads Closed - 10:00hrs to 20:00hrs Saturday 1st July & Sunday 2nd July A4067 Oystermouth Road/ A4067 Mumbles Road from its junction with Glamorgan Street to its junction with Brynmill Terrace. Access only to A4067 Oystermouth Road from its junction with Westway to its junction with Glamorgan Street. Access only to A4067 Mumbles Road from its junction with Brynmill Terrace to its junction with A4216 Sketty Lane. Access to Argyle Street via Civic Centre only. Parking Prohibition/Towaway Zone - 08:00hrs – 20:00hrs on Saturday 1st July & Sunday 2nd July A4067 Oystermouth Road / A4067 Mumbles Road from Westway to A4216 Sketty Lane. Road Closed 08:00hrs – 20:00hrs Saturday 1st July & Sunday 2nd July Pantycelyn Road - access for residents only. -

22 Rhyddings Park Road, Brynmill, Swansea SA2

22 Rhyddings Park Road, Brynmill, Swansea SA2 0AQ Offers in the region of £149,995 • Traditional Mid Terrace, • Three Reception Rooms, Gas Central Heating, Double Glazed, • Rear Garden With Rear Lane Access • Potential for parking if the garage is opened • EER E40 John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. NR/BT/58510/220817 FIRST FLOOR LANDING DESCRIPTION Loft access, door to: A spacious Mid Terrace BEDROOM 1 property ideal for conversion to 16'08 to alcove x 11'08 (5.08m HMO and is conveniently to alcove x 3.56m) located in Brynmill offering Two double-glazed windows to easy access to local amenities, front, radiator. -

Swanseabaycityofculture2017b

Swansea Bay City of Culture • 2017 OUR CREATIVE REVOLUTION X Contents Part A: Bid summary . 1 Part B: Vision, programme and impacts . 2 1 . The bid area . 2 2 . Overall vision . 4 3 . Cultural and artistic strengths . 6 4 . Social impacts . 14 5 . Economic impacts . 16 6 . Tourism impacts . 18 Part C: Delivery and capacity . 20 1 . Organisation, development, management and governance . 20 2 . Track record . 21 3 . Funding and budget . 21 4 . Partnerships . 22 5 . Risk assessment . 23 6 . Legacy . 24 Appendix A – Outline programme . 26 Appendix B – Summary of cultural and creative sectors in the city region . 34 Appendix C – Current state of our visitor economy . 36 Appendix D – Contributors to the bid . 38 Appendix E – Major events track record . 40 Appendix F – Outline budget . 42 Part A: Bid summary We are starting a creative revolution from the place that Our programme builds on our strengths – delivering events once led the world in the industrial revolution. Now, as then, and activities that have meaning to our existing culture, we have the raw materials – we want to take our creative which will appeal to wider audiences as well. We have taken resourceful people; our pioneering universities; our proud care to create a programme that has a legacy and that heritage; our contemporary arts; our incredible setting; our is sustainable – where there are one-off events they are vibrant and diverse communities; and forge them in our designed to leave a socio-cultural legacy of inspiration for a ‘crucible of talent’ as a creative city region. new generation and to raise our confidence as a city. -

Summer Open and Development FAQ's

Summer Open and Development FAQ’s #Summeriscoming The sun is still shining, summer holidays are here, and Swansea is ready. Here’s a few last minute reminders and tips to ensure you enjoy the event. Car Park The car park has 250 spaces, with additional spaces in an overflow located at the bottom of the slope; provisions are also in place to allow further spaces on the Swansea University campus. However please be aware, despite our best efforts – the car park is busy and fills quickly. To avoid disappointment, please arrive early. Where possible please arrange to car share or drop offs to help ease congestion. Alternatively there are 3 nearby pay and display car parks we recommend: Foreshore Car Park: 4 Mumbles Rd, Sketty, Swansea SA3 5AU – 0.6 miles 12 minute walk Recreation Ground Car Park: Mumbles Rd, Brynmill, Swansea SA2 0AU – 0.9 mile 19 minute walk Blackpill Area Car Park: 266 Derwen Fawr Rd, Sketty, Swansea SA3 5AT – 0.8 mile 15 minute walk The car park will be managed by security staff, please treat them with respect. Disrespectful or inappropriate behaviour towards staff will not be tolerated and you may be asked to leave the competition. Tickets Tickets and programmes can be purchased on arrival from the Swim Wales ticket desk, this is on the far end of the reception desk. Day tickets are £5 (adult), £3 concessionary and free for under 14’s; programmes are £5 including heat sheets and session times. Your ticket is a wristband, this must be worn to access the pool area.