Read an Extract from Lichfield and the Lands of St Chad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing and Economic Development Needs Assessment

Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council September 2019 Prepared by GL Hearn 65 Gresham St London EC2V 7NQ T +44 (0)20 7851 4900 glhearn.com Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council Contents Section Page 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC BASELINE 6 3 HOUSING NEED AND POPULATION GROWTH 18 4 EMPLOYMENT FORECASTS 27 5 ECONOMIC GROWTH AND HOUSING NEED 38 6 MARKET SIGNALS 47 7 AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEED 55 8 HOUSING MIX 72 9 NEEDS OF SPECIFIC GROUPS 84 10 COMMERICAL MARKET ASSESSMENT 98 11 EMPLOYMENT LAND REQUIREMENTS 115 12 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 132 GL Hearn Page 2 of 138 Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council Quality Standards Control The signatories below verify that this document has been prepared in accordance with our quality control requirements. These procedures do not affect the content and views expressed by the originator. This document must only be treated as a draft unless it is has been signed by the Originators and approved by a Business or Associate Director. DATE ORIGINATORS APPROVED September 2019 David Leyden Paul McColgan Strategic Planner Director Limitations This document has been prepared for the stated objective and should not be used for any other purpose without the prior written authority of GL Hearn; we accept no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than for which it was commissioned. GL Hearn Page 3 of 138 Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment Study is to assess future development needs for housing (both market and affordable) and employment across Lichfield and Tamworth. -

A Report on the Developments in Women's Ministry in 2018

A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry in 2018 WATCH Women and the Church A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry 2018 In 2019 it will be: • 50 years since women were first licensed as Lay Readers • 25 years since women in the Church of England were first ordained priests • 5 years since legislation was passed to enable women to be appointed bishops In 2018 • The Rt Rev Sarah Mullaly was translated from the See of Crediton to become Bishop of London (May 12) and the Very Rev Viv Faull was consecrated on July 3rd, and installed as Bishop of Bristol on Oct 20th. Now 4 diocesan bishops (out of a total of 44) are women. In December 2018 it was announced that Rt Rev Libby Lane has been appointed the (diocesan) Bishop of Derby. • Women were appointed to four more suffragan sees during 2018, so at the end of 2018 12 suffragan sees were filled by women (from a total of 69 sees). • The appointment of two more women to suffragan sees in 2019 has been announced. Ordained ministry is not the only way that anyone, male or female, serves the church. Most of those who offer ministries of many kinds are not counted in any way. However, WATCH considers that it is valuable to get an overview of those who have particular responsibilities in diocese and the national church, and this year we would like to draw attention to The Church Commissioners. This group is rarely noticed publicly, but the skills and decisions of its members are vital to the funding of nearly all that the Church of England is able to do. -

ST. PETER JUDGMENT 1) the Rector and Churchwardens Of

IN THE CONSISTORY CO URT OF THE DIOCESE O F LICHFIELD 3840 WOLVERHAMPTON: ST. P ETER JUDGMENT 1) The rector and churchwardens of St. Peter’s petition for a faculty to remove from the chancel the current electronic Makin organ together with one set of pews and to install a Bevington pipe organ in their place. For the reasons set out below I have concluded that this Petition must be refused. The Church. 2) The Collegiate Church of St. Peter is a Grade 1 listed building. It is a medieval building but underwent restorat ion work from 1852 to 1865. That work was designed by Ewan Christian and the chancel in its current form dates from that time. Pevsner’s description is that “ the long aisleless chancel and the polygonal apse are entirely by Christian in the style of the la te C13” . The chancel is indeed long. It has a high ceiling, a number of tall windows, and unadorned walls. The pews are carved dating from the Nineteenth Century restoration and they and the choir stalls are arranged in collegiate fashion. The chancel is o f the size and has the appearance of a small Oxbridge college chapel. The Makin organ is at the east end of the south side of the chancel and it together with two speakers associated with it and positioned at about the mid -point of the south wall are the o nly readily apparent recent alterations to the chancel. 3) The archway between the chancel and the nave is taken up with the pipework of the large Willis pipe organ which sounds into the nave. -

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options

For Official Use Respondent No: Representation Number: Received: Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options Please return to Lichfield District Council by 5pm on 24th January 2020, by: Email: [email protected] Post: Spatial Policy and Delivery, Lichfield District Council, District Council House, Frog Lane, Lichfield, WS13 6YZ. This form can also be completed on line using our consultation portal: http://lichfielddc- consult.limehouse.co.uk/portal PLEASE NOTE: This form has two parts: Part A: Personal details. Part B: Your representation(s). Part A: Personal details 1.Personal details1 2 2. Agent’s details (if applicable) Title Mrs First name Anna Last Name Miller Job Title (where relevant) Assistant Director – Growth and Regeneration Organisation (where relevant) Tamworth Borough Council House No./Street Marmion House, Lichfield Street Town Tamworth Post Code B79 7BZ Telephone Number 01827 709709 Email address (where relevant) anna- [email protected] 1 If an agent is being used only the title, name and organisation boxes are necessary but please don’t forget to complete all the Agent’s details. 2 Please note that copies of all comments received will be made available for the public to view, including your address and therefore cannot be treated as confidential. Lichfield District Council will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. Our Privacy Notice is at the end of this form. Part B: Your representation Where in the document does your comment relate: Part of document Various – please see below General comments: The Council notes that the proposed new local plan is intended to replace the current local plan strategy (2015) and local plan allocations document (2019). -

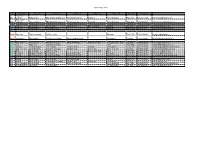

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Postcode Telephone ; Diocese of Dio Lichfield Niall Blackie FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01952 211320 [email protected] Diocese of Dio Lichfield Andrew Wynne FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01902 578066 [email protected] Lich Rugeley Mark Davys Deer's Leap Meadow Lane Little Haywood Stafford ST18 0TT 01889 883722 [email protected] Lich Lichfield Simon Baker 10 Mawgan Drive Lichfield WS14 9SD Ex-Directory [email protected] Salop Oswestry John Chesworth 21 Oerley Way Oswestry SY11 1TD 01691 653922 [email protected] Salop Shrewsbury Martin Heath Emmanuel Vicarage Mount Pleasant Road Shrewsbury SY1 3HY 01743 350907 [email protected] Stoke Eccleshall Nigel Clemas Whitmore Rectory Snape Hall Road Whitmore Heath Newcastle under Lyme ST5 5HS 01782 680258 [email protected] Stoke Leek Nigel Irons 24 Ashenhurst Way Leek ST13 5SB 01538 386114 [email protected] Stoke Stafford Richard Grigson The Vicarage Victoria Terrace Stafford Staffordshire ST16 3HA 07877 168498 [email protected] Stoke Stoke-on-Trent David McHardy St Francis Vicarage Sandon Road Meir Heath Stoke-on-Trent ST3 7LH 01782 398585 [email protected] Stoke Stone Ian Cardinal 11 Farrier Close Aston Lodge Park Stone ST15 8XP 01785 812747 [email protected] Stoke Uttoxeter Margaret Sherwin The Rectory 12 Orchard Close Uttoxeter ST14 7DZ 01889 560234 -

Weekly Newsletter St Joseph's and St Wilfrid's

Weekly Newsletter St Joseph’s and St Wilfrid’s A P ARISH OF T HE D I O CE SE OF H EXHAM & NE WCA ST L E R EGISTERED CHARITY NO.1143450 PARISH PRIEST: VERY REV DR MICHAEL BROWN PRESBYTERY: ST JOSEPH’S HIGH WEST STREET GATESHEAD NE8 1LX TELEPHONE NOS.: ST JOSEPH’S: 477 1631 ST WILFRID’S: 477 1631 http://www.stjosephscatholicchurchgateshead.org.uk/ BOOKINGS FOR ST JOSEPH’S HALL: 07989 734644 email: [email protected] Week Commencing 17th March 2019 St Patrick’s Day Second Sunday of Lent Saint Patrick’s Feast Day 17th March REMEMBER 19th March 6pm CMUK th 19 March 7pm High Mass Services for Bishop Robert’s Installation followed by shared table (all held at St Contrary to popular belief Ireland’s National Mary’s Cathedral) th colour has not always been green. Saint 20 March 10am th th Sunday 24 March - Patrick's colour was blue, and from the 12 Community 4.30 pm Solemn century blue adorned the Ancient Irish flags Choir Vespers and the Royal Court. Everybody in the 22nd March 5pm Diocese is invited to The Shamrock has always been the National Good attend. emblem of Ireland and its banning by the Shepherd for Monday 25th March English only served to strengthen its ages 3-6yrs - 12 noon Episcopal symbolism reflected in the green uniforms Installation Mass worn by Irish soldiers to show their solidarity Entry by invitation against the British who wore red. only, you will not be During the rebellion of 1798 the clover permitted without a ticket. -

Wills on Microfilm at the Hive

Wills on Microfilm at The Hive Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service Contents Wills on Microfilm at The Hive .................................................................... 0 Wills and Probate records ........................................................................ 3 Why we have wills ................................................................................ 3 Using the Handlist ................................................................................. 4 Information wills can provide: ................................................................ 5 Limitations of wills include: .................................................................... 5 Other Sources:...................................................................................... 5 Worcester Consistory Court Registered Wills 1451-1642 ........................ 7 Worcestershire Wills Proved in London 1652-1739 ................................. 7 Worcestershire Original Wills: Part 1- 1493-1694 .................................. 8 Worcestershire Original Wills: Part 2- 1694-1857 .................................. 28 Wills 1858 - 1928 ................................................................................... 53 Peculiars................................................................................................ 58 Lichfield Wills ......................................................................................... 64 Northampton Wills ................................................................................. 65 -

Veterans Memorial (By Names & Numbers).Xlsx

Name Service Branch Conflict Monument ID# Entries Emblem at Top of Mon. Abbott, Donald H. US Army WWII 18-B-Right Col 9 3632 Disable American Veterans Abbott, James P. US Air Force Persian Gulf 18-B-Right Col 23 3646 Disable American Veterans Abbott, John D. US Air Force Vietnam 18-B-Right Col 21 3644 Disable American Veterans Abbott, John D. Jr. US Air Force Panama 18-B-Right Col 22 3645 Disable American Veterans Abbott, Robert P. US Marine Corps Vietnam 28-B-Left Col. 19 5748 Air National Guard Achorn, Richard L. US Navy WWII 8-A Right Col. 46 1612 POW-MIA Logo Adamen, Stanley M. US Army WWII 17-B-Left Col 14 3367 AMVETS Adams, Bernard L. Jr. US Army WWII 28-A-Left Col. 14 5635 Air National Guard Adams, Byron C. Jr. US Army WWII 11-B-Right Col. 44 2366 Veterans of Foreign Wars Adams, Garfield D. US Navy WWII 20-A-Right Col 10 3957 US Army WAC Logo Adams, Harold C. US Army WWII 22-A-Left Col 15 4340 US Navy Waves Adams, Harold F. US Army Vietnam 32-A-Right Col. 21 6560 Destroyer Escort Assoc. Adams, Preston G. US Navy WWII 21-A-Left Col 24 4133 US Air Force Women Adams, Ralph S. US Army Korea 2-B Right Col. 33 411 State of Maine Seal Adams, Richard C. US Army WWI 22-B-Left Col 11 4444 US Navy Waves Adams, Richard M. US Army WWII 10-B Right Col. 40 2146 Order of the Purple Heart Adams, Robert P. -

Curacy in the Diocese of Lichfield

Curacy in the Diocese of Lichfield Title post in the St Mary’s | inclusive catholic a town centre church with a civic role at parishes of the heart of the county Saint Mary’s, Stafford St Chad’s | inculsive catholic an ancient High Street parish with a Saint Chad’s, Stafford ministry to the shopping area centre Saint Leonard’s, St Leonard’s | central a small rural church on the route of HS2 Marston with a new parish being built around it Welcome to Lichfield Diocese Cradled at the intersection of the Midlands and the Shropshire, to the sparsest upland communities of North, and the interface between England and the Staffordshire Moorlands and Welsh Borders. Wales, the Diocese of Lichfield is the ancient centre And we embrace the widest spectrum of church of Christianity in what was the Kingdom of Mercia. traditions – evangelical and catholic, liberal and We are rightfully grateful for the inheritance we conservative, choral and charismatic, as we journey have from St Chad that leads us to focus on together – as a colleague recently put it, it is our Discipleship, Vocation and Evangelism as we live goal to be a ‘spacious and gracious diocese’. and serve among the communities of Staffordshire, northern Shropshire and the Black Country. ‘…a spacious and Wherever in the Diocese you may be placed, you will benefit from being part of a wider family, gracious diocese.’ mixing with people serving in a wide variety of contexts – from the grittiest inner-city It is my determination and that of my fellow- neighbourhoods of Stoke and the Black Country, to bishops that your calling to a title post will be a the leafiest rural parishes of Staffordshire and time of encouragement, ongoing formation, challenge and (while rarely unbridled) joy. -

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the City Of

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the city of Lichfield in Lichfield District Council area: Specialist Housing for Older People December 2018 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 1 Contents 1 Lichfield City Mapping ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Lichfield City Population Demographics ..................................................................... 3 1.2 Summary of demographic information ..................................................................... 11 1.3 Lichfield Locality Analysis .......................................................................................... 12 1.4 Access to Local Facilities and Services ...................................................................... 12 1.5 Access to local care facilities/age appropriate housing in Lichfield ......................... 23 2 Lichfield summary ............................................................................................................. 30 2.1 Lichfield Locality Population Demographics ............................................................. 30 2.2 Access to retail, banking, health and leisure services ............................................... 31 2.3 Access to specialist housing and care facilities ......................................................... 32 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 2 1 Lichfield City Mapping A 2km radius from the post code WS13 6JW has been set for the locality analysis which -

Memorials of Old Staffordshire, Beresford, W

M emorials o f the C ounties of E ngland General Editor: R e v . P. H. D i t c h f i e l d , M.A., F.S.A., F.R.S.L., F.R.Hist.S. M em orials of O ld S taffordshire B e r e s f o r d D a l e . M em orials o f O ld Staffordshire EDITED BY REV. W. BERESFORD, R.D. AU THOft OF A History of the Diocese of Lichfield A History of the Manor of Beresford, &c. , E d i t o r o f North's .Church Bells of England, &■V. One of the Editorial Committee of the William Salt Archaeological Society, &c. Y v, * W ith many Illustrations LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & SONS, 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE, W. 1909 [All Rights Reserved] T O T H E RIGHT REVEREND THE HONOURABLE AUGUSTUS LEGGE, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF LICHFIELD THESE MEMORIALS OF HIS NATIVE COUNTY ARE BY PERMISSION DEDICATED PREFACE H ILST not professing to be a complete survey of Staffordshire this volume, we hope, will W afford Memorials both of some interesting people and of some venerable and distinctive institutions; and as most of its contributors are either genealogically linked with those persons or are officially connected with the institutions, the book ought to give forth some gleams of light which have not previously been made public. Staffordshire is supposed to have but little actual history. It has even been called the playground of great people who lived elsewhere. But this reproach will not bear investigation.