A Focus on Lichfield 2015 October 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing and Economic Development Needs Assessment

Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council September 2019 Prepared by GL Hearn 65 Gresham St London EC2V 7NQ T +44 (0)20 7851 4900 glhearn.com Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council Contents Section Page 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC BASELINE 6 3 HOUSING NEED AND POPULATION GROWTH 18 4 EMPLOYMENT FORECASTS 27 5 ECONOMIC GROWTH AND HOUSING NEED 38 6 MARKET SIGNALS 47 7 AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEED 55 8 HOUSING MIX 72 9 NEEDS OF SPECIFIC GROUPS 84 10 COMMERICAL MARKET ASSESSMENT 98 11 EMPLOYMENT LAND REQUIREMENTS 115 12 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 132 GL Hearn Page 2 of 138 Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council Quality Standards Control The signatories below verify that this document has been prepared in accordance with our quality control requirements. These procedures do not affect the content and views expressed by the originator. This document must only be treated as a draft unless it is has been signed by the Originators and approved by a Business or Associate Director. DATE ORIGINATORS APPROVED September 2019 David Leyden Paul McColgan Strategic Planner Director Limitations This document has been prepared for the stated objective and should not be used for any other purpose without the prior written authority of GL Hearn; we accept no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than for which it was commissioned. GL Hearn Page 3 of 138 Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment August 2019 Lichfield District Council and Tamworth Borough Council 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Housing and Economic Development Need Assessment Study is to assess future development needs for housing (both market and affordable) and employment across Lichfield and Tamworth. -

Lichfield Community Safety Delivery Plan

Lichfield District Community Safety Delivery Plan 2017 - 2020 Foreword Our aim is to ensure that Lichfield District remains one of the safest places in the county and this Delivery Plan will provide the means by which the community safety priorities highlighted in the 2016 Strategic Assessment can be delivered. Members of our Safer Community Partnership will lead on the delivery of our priority actions, but we cannot make this happen on our own. We hope that partners, stakeholders, local people and communities will take responsibility, demonstrate commitment and make a real contribution to help realise our vision for a safe District. The Partnership has embraced a number of changes over recent years, not least the challenges brought about by the current financial pressures experienced by all public sector organisations. Difficult decisions are having to be made which impact on people's quality of life, so it's important we utilise what funding we do have effectively. Other challenges we need to be mindful of are national and international terrorism and violence which has had a high media profile over recent times, together with the extent of child sexual exploitation (CSE) and Modern Day Slavery (MDS) within our communities. Much more emphasis is being placed on identifying and supporting people, especially young people and children, who are vulnerable to any form of exploitation and radicalisation. The opportunities and threats of social media have also become a major consideration going forward as we need to support local residents, especially young people to use it safely. Community safety is a complex and challenging area of work and we are grateful for the support and enthusiasm of all who are driven to continually improve the quality of life for people who live in the District. -

Read an Extract from Lichfield and the Lands of St Chad

Contents List of illustrations vii General Editor’s preface ix Acknowledgements xi Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Early medieval communities 2 The communities of the lands of St Chad 9 1 Lichfield and the English Church 11 The episcopal list tradition 12 Theodore’s church 19 Church and kingdom 21 The division of the Mercian see 26 The English Church and the Mercian kingdom 33 The English Church from the late ninth century 40 Conclusions 44 2 The Church of Lichfield 48 The Lastingham narrative 48 Bishop Chad and Bishop Wilfrid 54 The diocesan community 60 The Church of Lichfield and the diocesan community 80 3 The cathedral and the minsters 86 Hunting for minsters 87 Lichfield cathedral 110 Minsters attested by pre-c.1050 hagiography 123 Minsters attested by post-c.1050 hagiography 137 Minsters securely attested by stone sculpture 141 Minsters less securely attested 146 Minsters and communities 150 4 The bishop and the lords of minsters 156 Ecclesiastical tribute 157 Episcopal authority over the lords of minsters 166 Conclusions 175 5 The people 177 Agricultural communities and the historic landscape 177 Domainal communities and the possession of land 186 Brythonic place-names 190 Old English place-names 195 Eccles place-names 203 Agricultural and domainal communities in the diocese of Lichfield 206 6 The parish 216 Churches and parishes 217 Churches, estates and ‘regnal territories’ 225 Regnal territories and the regnal community 240 A parochial transformation 244 Conclusion 253 Bibliography 261 Index 273 Introduction This book explores a hole at the heart of Mercia, the great Midland kingdom of early medieval England. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

ST. PETER JUDGMENT 1) the Rector and Churchwardens Of

IN THE CONSISTORY CO URT OF THE DIOCESE O F LICHFIELD 3840 WOLVERHAMPTON: ST. P ETER JUDGMENT 1) The rector and churchwardens of St. Peter’s petition for a faculty to remove from the chancel the current electronic Makin organ together with one set of pews and to install a Bevington pipe organ in their place. For the reasons set out below I have concluded that this Petition must be refused. The Church. 2) The Collegiate Church of St. Peter is a Grade 1 listed building. It is a medieval building but underwent restorat ion work from 1852 to 1865. That work was designed by Ewan Christian and the chancel in its current form dates from that time. Pevsner’s description is that “ the long aisleless chancel and the polygonal apse are entirely by Christian in the style of the la te C13” . The chancel is indeed long. It has a high ceiling, a number of tall windows, and unadorned walls. The pews are carved dating from the Nineteenth Century restoration and they and the choir stalls are arranged in collegiate fashion. The chancel is o f the size and has the appearance of a small Oxbridge college chapel. The Makin organ is at the east end of the south side of the chancel and it together with two speakers associated with it and positioned at about the mid -point of the south wall are the o nly readily apparent recent alterations to the chancel. 3) The archway between the chancel and the nave is taken up with the pipework of the large Willis pipe organ which sounds into the nave. -

Dentalroots Issue 3 2012 the Dentistry Alumni Magazine

DentalROOTS Issue 3 2012 The Dentistry alumni magazine The war against gum disease Also inside: Dentistry’s new home on track for 2014; Community dental expert recalls life in the Firm 2 DentalROOTS Fruit and vegetable compound offers hope against gum disease Scientists at the University of Birmingham have found that supplementing the diet with a special Welcome combination of fruit and vegetable juice powder concentrates may Welcome to the 2012 edition of DentalROOTS, our annual publication intended to keep alumni help to combat chronic gum disease informed on developments in the School of Dentistry during the past year. when combined with conventional dental therapy. We continue to take a forward-looking approach to provide our students with a distinctive high-quality experience. Our students stand tall with no side lean, given the end of the student The results of a preliminary randomised cabinets and also their performance in the national recruitment process and finals. This year saw controlled study show that taking a daily the introduction of a new national recruitment system for foundation training. Any change can be dose of capsules containing concentrated stressful and one such as this even more so given the potential for having a profound impact on phytonutrients improved clinical outcomes the graduates, future careers. The 2012 Birmingham final year students fared well, all passed for patients with chronic periodontitis finals and all were offered a foundation training place; a fortunate position to be in given that (deep-seated gum disease) in the two not all UK graduates managed to secure a place at the time of writing. -

Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options

For Official Use Respondent No: Representation Number: Received: Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options Please return to Lichfield District Council by 5pm on 24th January 2020, by: Email: [email protected] Post: Spatial Policy and Delivery, Lichfield District Council, District Council House, Frog Lane, Lichfield, WS13 6YZ. This form can also be completed on line using our consultation portal: http://lichfielddc- consult.limehouse.co.uk/portal PLEASE NOTE: This form has two parts: Part A: Personal details. Part B: Your representation(s). Part A: Personal details 1.Personal details1 2 2. Agent’s details (if applicable) Title Mrs First name Anna Last Name Miller Job Title (where relevant) Assistant Director – Growth and Regeneration Organisation (where relevant) Tamworth Borough Council House No./Street Marmion House, Lichfield Street Town Tamworth Post Code B79 7BZ Telephone Number 01827 709709 Email address (where relevant) anna- [email protected] 1 If an agent is being used only the title, name and organisation boxes are necessary but please don’t forget to complete all the Agent’s details. 2 Please note that copies of all comments received will be made available for the public to view, including your address and therefore cannot be treated as confidential. Lichfield District Council will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. Our Privacy Notice is at the end of this form. Part B: Your representation Where in the document does your comment relate: Part of document Various – please see below General comments: The Council notes that the proposed new local plan is intended to replace the current local plan strategy (2015) and local plan allocations document (2019). -

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2

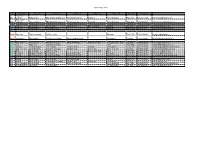

As at 11 May 2020 Ar Surrogate Person Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Postcode Telephone ; Diocese of Dio Lichfield Niall Blackie FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01952 211320 [email protected] Diocese of Dio Lichfield Andrew Wynne FBC Manby Bowdler LLP 6-10 George Street Snow Hill Wolverhampton WV2 4DN 01902 578066 [email protected] Lich Rugeley Mark Davys Deer's Leap Meadow Lane Little Haywood Stafford ST18 0TT 01889 883722 [email protected] Lich Lichfield Simon Baker 10 Mawgan Drive Lichfield WS14 9SD Ex-Directory [email protected] Salop Oswestry John Chesworth 21 Oerley Way Oswestry SY11 1TD 01691 653922 [email protected] Salop Shrewsbury Martin Heath Emmanuel Vicarage Mount Pleasant Road Shrewsbury SY1 3HY 01743 350907 [email protected] Stoke Eccleshall Nigel Clemas Whitmore Rectory Snape Hall Road Whitmore Heath Newcastle under Lyme ST5 5HS 01782 680258 [email protected] Stoke Leek Nigel Irons 24 Ashenhurst Way Leek ST13 5SB 01538 386114 [email protected] Stoke Stafford Richard Grigson The Vicarage Victoria Terrace Stafford Staffordshire ST16 3HA 07877 168498 [email protected] Stoke Stoke-on-Trent David McHardy St Francis Vicarage Sandon Road Meir Heath Stoke-on-Trent ST3 7LH 01782 398585 [email protected] Stoke Stone Ian Cardinal 11 Farrier Close Aston Lodge Park Stone ST15 8XP 01785 812747 [email protected] Stoke Uttoxeter Margaret Sherwin The Rectory 12 Orchard Close Uttoxeter ST14 7DZ 01889 560234 -

Land North of Ashby Road, Tamworth, Staffordshire Application Ref: 14/00516/Outmei

Mrs Lizzie Marjoram Our ref: APP/K3415/V/17/3174379 Bird Wilford and Sale Solicitors Your ref: (bws) EHM/TS/ARKALL 19-20 Church Gate (savills) WIPL321567 LOUGHBOROUGH Leicestershire LE11 1UD Richard Shaw Savills Wessex House Priors Walk 7 June 2018 East Borough Wimborne BH21 1PB Dear Sir / Madam TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 77 APPLICATION MADE BY BARWOOD STRATEGIC LAND II LLP (BSL) LAND NORTH OF ASHBY ROAD, TAMWORTH, STAFFORDSHIRE APPLICATION REF: 14/00516/OUTMEI 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of Ken Barton BSc(Hons) DipArch DipArb RIBA FCI Arb, who held a public local inquiry between 16 and 25 January 2018 into your client’s application for outline planning permission for up to 1,000 homes, primary school, local centre (up to 40 m²), public open space, landscaping and associated infrastructure in accordance with application ref: 14/00516/OUTMEI dated 16 May 2014. 2. On 20 April 2017, the Secretary of State directed, in pursuance of Section 77 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, that your client’s application be referred to him instead of being dealt with by the local planning authority. Inspector’s recommendation and summary of the decision 3. The Inspector recommended that the application be approved. 4. For the reasons given below, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s conclusions, and agrees with his recommendation. He has decided to grant outline planning permission. A copy of the Inspector’s report (IR) is enclosed. All references to paragraph numbers, unless otherwise stated, are to that report. -

Baseline Report: Climate Change Mitigation & Adaptation Study

Baseline Report Climate Change Adaptation & Mitigation Staffordshire County Council Project number: 60625972 16 October 2020 Revision 04 Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Harper Robertson Luke Aldred Luke Aldred Matthew Turner Senior Sustainability Associate Director Associate Director Regional Director Consultant Alice Purcell Graduate Sustainability Consultant Luke Mulvey Graduate Sustainability Consultant Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 01 20 February 2020 Skeleton Report Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 02 31 March 2020 Draft for issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 03 11 September 2020 Final issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 04 16 October 2020 Updated fuel consumption Y Luke Associate and EV charging points Aldred Director Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council AECOM Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council Prepared by: Harper Robertson Senior Sustainability Consultant E: [email protected] AECOM Limited Aldgate Tower 2 Leman Street London E1 8FA United Kingdom aecom.com © 2020 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. -

Wills on Microfilm at the Hive

Wills on Microfilm at The Hive Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service Contents Wills on Microfilm at The Hive .................................................................... 0 Wills and Probate records ........................................................................ 3 Why we have wills ................................................................................ 3 Using the Handlist ................................................................................. 4 Information wills can provide: ................................................................ 5 Limitations of wills include: .................................................................... 5 Other Sources:...................................................................................... 5 Worcester Consistory Court Registered Wills 1451-1642 ........................ 7 Worcestershire Wills Proved in London 1652-1739 ................................. 7 Worcestershire Original Wills: Part 1- 1493-1694 .................................. 8 Worcestershire Original Wills: Part 2- 1694-1857 .................................. 28 Wills 1858 - 1928 ................................................................................... 53 Peculiars................................................................................................ 58 Lichfield Wills ......................................................................................... 64 Northampton Wills ................................................................................. 65 -

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the City Of

Staffordshire County Council GIS Locality Analysis for the city of Lichfield in Lichfield District Council area: Specialist Housing for Older People December 2018 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 1 Contents 1 Lichfield City Mapping ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Lichfield City Population Demographics ..................................................................... 3 1.2 Summary of demographic information ..................................................................... 11 1.3 Lichfield Locality Analysis .......................................................................................... 12 1.4 Access to Local Facilities and Services ...................................................................... 12 1.5 Access to local care facilities/age appropriate housing in Lichfield ......................... 23 2 Lichfield summary ............................................................................................................. 30 2.1 Lichfield Locality Population Demographics ............................................................. 30 2.2 Access to retail, banking, health and leisure services ............................................... 31 2.3 Access to specialist housing and care facilities ......................................................... 32 GIS Locality Analysis: The City of Lichfield Page 2 1 Lichfield City Mapping A 2km radius from the post code WS13 6JW has been set for the locality analysis which