LSU and Southern University Compete For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Time Champs First Time Conference Volleyball Champions Jackson State and Maryland-Eastern Shore Will Face a Tough Task in Ncaas

Marching 100 Drum major dies after Florida Classic. Band Director fired.6 NOVEMBER 29-DEcEMBER 6, 2011 FOllOw Us theyardweekly theyardhbcu theyardhbcu First Time Champs First time Conference Volleyball Champions Jackson State and Maryland-Eastern Shore will face a tough task in NCAAs. 3 2 3 1 lADY BUllDOGs wHOOP TENNEssEE TEcH Whiquitta Tobar (above) led the Lady Bulldogs with 17 points in Alabama A&M’s 61-35 victory at Elmore Gym Alyssa Strickland and NaDra Robertson came up big for A&M as the duo finished with 11 points Jackson State celebrates after their victory over Alabama A&M. apiece on 8-of-12 shooting. BALTIMORE—The University 11 digs, adding three aces and a of Maryland Eastern Shore won pair of assists. Vaitai also got a QB READY the Mid-Eastern Athletic Con- double-double, earning 10 kills, Alabama A&M coach Anthony ference Championship for the 11 digs, two aces and a pair of Jones said Tuesday that he expects first time ever with a five-set vic- blocks. Ibe amassed nine kills starting quarterback Deaunte tory over Florida A&M (15-25, and six blocks. Vicic set 46 as- Mason, who sprained the medial 25-17, 25-21, 18-25, 15-12) at sists, adding six blocks plus a kill the Physical Education Complex and ace. Lea’Aetoa had six kills collateral ligament in his left knee at Coppin State University. and three aces while Williams in the regular-season finale against With the win, UMES has got five kills and two blocks. Prairie View, to be ready when the earned an automatic berth into For the Rattlers, Ceccarelli Bulldogs take on Grambling in the the NCAA Tournament. -

GSU NOTES CELEBRATION BOWL.Indd

2016SWACCHAMPIONS | 2016AIRFORCERESERVEBOWLCHAMPIONS | 2016BLACKCOLLEGENATIONALCHAMPIONS GAME 13 2017SCHEDULE&RESULTS #12/#13 GRAMBLING STATE Game Celebration Bowl (11-1, 7-0 SWAC) Date Saturday, Dec. 16 Time 11 a.m. Sept. 2 at Tulane% L, 14-43 Location Atlanta, Ga. Sept. 9 NORTHWESTERN STATE W, 23-10 Venue Mercedes-Benz Stadium Sept. 16 JACKSON STATE%! W, 36-21 Capacity 71,000 Sept. 23 at Mississippi Valley State* W, 38-6 Television ABC Sept. 30 vs. Clark Atlanta** W, 31-20 Radio 99.3 FM/97.3 FM Oct. 7 vs. Prairie View A&M*^ W, 34-21 Series Record GSU leads, 4-3 Oct. 21 ALCORN STATE* W, 41-14 GRAMBLINGSTATE NORTHCAROLINAA&T Oct. 28 TEXAS SOUTHERN*# W, 50-24 Series Streak: GSU lost 2 Nov. 4 at Arkansas-Pine Bluff* W, 31-26 TIGERS Last Meeting 1996 AGGIES Nov. 11 at Alabama State* W, 24-7 11-1 Result N.C. A&T, 17-12 11-0 Nov. 25 vs. Southern*^^ W, 30-21 7-0SWAC 8-0MEAC Dec. 2 vs. Alcorn State$ W, 40-32 Dec. 16 North Carolina A&T State+ 11 a.m. THE GAME: This is what the fan want and this is what the fans will get. It doesn’t get any better than the SWAC’s best team going up against the MEAC’s best team with a chance to win an HBCU National Championship. Not only do you have two great teams, but you will also have two outstanding coaches in Broderick Fobbs and Rod Broadway. * - Southwestern Athletic Conference Game | ** - Chicago Classic (Soldier Field) ^ - Texas State Fair Classic (Cotton Bowl) | ^^ - Bayou Classic (Mercedes-Benz Superdome) But the comparisons don’t just stop there. -

2010 Delaware State Football Game 11 Delaware State University Hornets (2-8; 1-6 Meac) Vs

2010 DELAWARE STATE FOOTBALL GAME 11 DELAWARE STATE UNIVERSITY HORNETS (2-8; 1-6 MEAC) VS. HOWARD UNIVERSITY BISON (1-9; 0-7 MEAC) SAT., NOV. 20, 2010 (1:00 P.M) GREENE STADIUM (7,086) - WASHINGTON, D.C. DSU Athletic Media Relations: Dennis Jones (football contact) - (302) 857-6068/office; (302) 270-6088/cell; email: [email protected] DELAWARE STATE VS HOWARD 2010 DELAWARE STATE SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent TV Time/Result Series Sep. 5 vs. Southern ESPN/ESPNHD/ESPN3.com L, 27-37 DSU leads 2-1 Larrone Moore has 186 all-purpose yards, two long TDs Sep. 11 *FLORIDA A&M - L, 14-17. FAMU leads 20-8 Delaware State: 2-8; 1-6 MEAC Howard: 1-9; 0-7 MEAC Hornets cough up two leads; hurt by lack of field goal kicker Howard leads 34-31-1 The Series: Sep. 25 at Coastal Carolina - L, 14-34 CCU leads 2-1 Location: Green Stadium (7,086) - Washington, D.C. DSU shutout until last two minutes (Surface— Artificial) National Rankings: Delaware State and Howard are not Sep. 30 *HAMPTON ESPNU L, 14-20 HAM leads 23-13 listed in any national Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) or Black College polls. Pirates win third straight at Alumni Stadium Pressbox Phone: 202-806-5488; 89; 91 Oct. 9 *at Bethune-Cookman - L, 24-47 DSU leads 19-16 Delaware State Head Coach Al Lavan: Al Lavan Wildcats racked up 590 yards (Colorado State, ‘68) is in his seventh season as head coach of the Hornets. He holds a 40-36 overall record (.526), includ- ing a 33-21 mark (.611) vs. -

Meac Legends of Coaching Candidates - Accolades and Supporting Information

MEAC LEGENDS OF COACHING CANDIDATES - ACCOLADES AND SUPPORTING INFORMATION - Criteria: Candidates for the MEAC Legends of Coaching must have served as a head coach in the MEAC for a period of at least four (4) years, must have won at least one (1) MEAC championship and must have had a winning record. The candidates are listed here alphabetically by last name. • TIM ABNEY (Women’s Basketball, N.C. A&T State) – Served as head women’s basketball coach for the Aggies from 1986-99, compiling a record of 116-87 in league play and 191-162 overall…led the Aggies to their first-ever MEAC regular-season championship, to three straight titles from 1987-90 and the program’s first- ever conference tournament title…is the NCAT women’s basketball all-time leader in coaching victories. • CY ALEXANDER (Men’s Basketball, S.C. State/N.C. A&T State) – Was head men’s basketball coach at S.C State from 1987-99 and at N.C. A&T State from 2012-16…at SCSU, won five (5) regular season and six (6) MEAC tournament championships while compiling a record of 204-80 (276-200 overall)…the 1988-89 team won its first-ever MEAC tournament title and subsequent berth to the NCAA Div. I tournament…led Bulldogs to a total of five (5) automatic berths to the NCAA tournament…in his first season at NCAT, led the Aggies to the MEAC tournament title and automatic berth to the NCAA tournament. • JASON BEVERLIN (Baseball, Bethune-Cookman) – Compiled a conference record of 95-47 in five years as head coach of the Wildcats (2013-17) as well as an overall record of 179-177 overall…his teams captured four (4) conference championships (2012, 2014, 2016, 2017)...the 2017 team became the first MEAC program to advance to an NCAA Regional when the Wildcats made it to the NCAA Gainesville Regional Final…named MEAC Baseball Championship Outstanding Coach four (4) times (2012, 2014, 2016, 2017). -

Three Baccalaureate Degrees on 2012 Roster

Three Baccalaureate Degrees on 2012 Roster FAMU Athletics is dedicated The results have been as- Hepburn twice won the Army to its student-athletes, both on and tounding. “We must continue to Strong award last year and is ex- off the field of play. Evidence of show our dedication to our student- pected to have his breakout season. this can be taken from the fact that athletes by providing them with Scott, has been selected for two 40 student-athletes, 15 in football every possible resource to be suc- watch lists in this preseason. The alone, attained their degrees this cessful,” FAMU director of athlet- Stanford University transfer is also past Spring. ics Derek Horne said. an ordained minister. Among the crowd of student- The three graduates will be These three accomplished athletes who walked across the stage enrolled in graduate studies during football players are far from the on Apr.28, were three current mem- the Fall semester. Hartley, received norm in college athletics, but exact- bers of the Rattler Football squad. a bachelor’s degree in Political Sci- ly what the mission of Florida A&M Offensive lineman Robert Hartley, ence, Hepburn acquired a bach- University and FAMU Athletics linebacker Brandon Hepburn and elor’s degree in chemistry and Scott calls for. Congratulations to our ul- nosetackle Padric Scott all met their attained his degree in biology. timate student-athletes for their suc- academic goals. Hartley is a preseason All- cess on and off the field of play. The athletic department made MEAC selection at offensive line. a commitment to the academic suc- cess of it’s student-athletes by devel- oping and staffing the Athletic Aca- demic Center. -

A&T, Alcorn Meet for Third Time In

FOR THE WEEK OF DECEMBER 17 - 23, 2019 C E L E B R A T I O N B O W L V NORTH CAROLINA A&T ALCORN STATE AGGIES (8-3) BRAVES (9-3) CHAMPION CHAMPION MID EASTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE vs. SOUTHWESTERN ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION ™ TEAM RECORD 2019 RESULTS 2019 RESULTS TEAM RECORD 2019 Overall: 8-3 NC A&T 8-3 ALCORN STATE 9-3 2019 Overall: 9-3 2019 MEAC: 6-2 24....................Elon ...................21 W 10.....@ Southern Mississippi.......38 L 2019 SWAC: 7-1 2019 BCSP Ranking: T 1st 13.................@ Duke ..................45 L 45........ Mississippi College .......... 7 W 2019 BCSP Ranking: T 1st All-Time vs. Alcorn: 2-1 27.....@ Charleston Southern ....21 W 14......... @ McNeese State ...........17 L All-Time vs. NC A&T: 1-2 Last Time vs. Alcorn: 24-22 W, '18 37...........Delaware State. ............0 W 45..........Prairie View A&M.......... 41 W Last Time vs. NC A&T: 24-22 L, '18 45.....Mississippi Valley State ..... 19 W Celebration Bowl: 3-0, (Last '18) 58.......... @ Norfolk State...........19 W Celebration Bowls: 0-2, (Last '18) 35..........@ Alabama State ........... 7 W MEAC Championships: 9 31........... @ Florida A&M ......34, OT L SWAC Championships: 17 42...........Savannah State ........... 17 W 64.................Howard. ..................6 W Celebration Bowl Trophy & Helmets 27................ Southern ................ 13 W CELEBRATE COACH'S RECORD 22.... @ South Carolina State ....20 W COACH'S RECORD Alma Mater: Miss. Valley State ('82) 16........ @ Grambling State ...19,OT L Alma Mater: Alcorn State ('92) A CHARM: SWAC champion 16.......... @ Morgan State ............22 L Head Coach Record vs. -

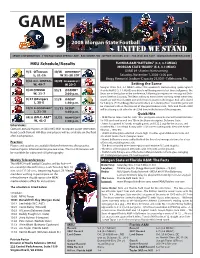

Game 9 ONE to WATCH Tracking the Bears Sophomore Cornerback Darren Mckhan Has Been One of the Standouts on the Defensive Side of the Ball

GAME 22008008 MMorganorgan StateState FFootballootball 9 uunitednited wewe standstand SPORTS INFORMATION • 1700 EAST COLD SPRING LANE • BALTIMORE, MD • OFFICE (443) 885-3831 • FAX (443) 885-8307 • MORGANSTATEBEARS.COM 198 MSU Schedule/Results FLORIDA A&M “RATTLERS” (3-3, 3-1 MEAC) MORGAN STATE “BEARS” (5-3, 3-1 MEAC) 9/6 @Towson 10/18 @HOWARD* GAME #9 - Rattlers Homecoming L, 21-16 W 31-30 2OT Saturday, November 1, 2008 • 3:00 p.m. Bragg Memorial Stadium (Capacity 25,500) • Tallahassee, Fla. 9/13 N.C. CENTRAL 10/25 DELAWARE ST.* W, 49-7 W 20-3 Setting the Scene Morgan State (5-3, 3-1 MEAC) enters this weekend’s Homecoming game against 9/20 @WSSU 11/1 @FAMU* Florida A&M (3-3, 3-1 MEAC) on a bit of a roll having won its last three ballgames. The W, 21-7 3:00 p.m. Bears are in third place in the conference, following an impressive win against Dela- ware State last Saturday. The Bears will try to extend their winning streak when they 9/27 @Rutgers 11/8 @NSU* match-up with Florida A&M, one of the hottest teams in the league. Kick-off is slated L, 38-0 1:00 p.m. for 3:00 p.m. (EST) at Bragg Memorial Stadium on Saturday (Nov. 1) and the game will be streamed LIVE on the internet at Morganstatebears.com. MSU and Florida A&M 10/4 B-COOKMAN* 11/15 SCSU* will be playing each other for the 23rd time in the history of the programs. -

Football Quick Facts.Indd

22018018 GGramblingrambling SStatetate FFOOTBALLOOTBALL QQuickuick FFactsacts GRAMBLING STATE UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF Location Grambling, La. Head Coach Broderick Fobbs Founded 1901 Alma Mater Grambling State, 1997 Enrollment 5,188 Record at GSU (Years) 39-11 (4 seasons) Mascot Tigers Overall Record (Years) 39-11 (4 seasons) School Colors Black & Gold Director of Football Operations Michael Armstrong Affi liation NCAA Division I FCS Offi ce Phone 318.274.2327 Conference Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC) Offi ce Fax 318.274.2761 Stadium Eddie G. Robinson Memorial Stadium Best Time/Day to Reach Coach Contact Football Capacity 19,600 Offensive Coordinator/Offensive Line Reginald Nelson Surface Artifi cial Turf Alma Mater McNeesee State, 1998 President Richard J. Gallot, Jr. Defensive Coordinator/Defensive Line Everett Todd Alma Mater Grambling State, 1987 Alma Mater Rice, 1984 Director of Athletics Paul A. Bryant Quarterbacks Kendrick Nord Alma Mater Alaska Pacifi c, 1990 Alma Mater Grambling State, 2012 Deputy Director of Athletics/Business Manager Terlynn Olds Wide Receivers Quentin Burrell Alma Mater Saint Leo, 1998 Alma Mater Notre Dame, 2005 Associate Director of Athletics/SWA Wanda Currie Running Backs Lee Fobbs Alma Mater Grambling State, 1984 Alma Mater Grambling State, 1973 Assistant AD for Marketing and Communications Karen M. Carty Tight Ends Darrell Kitchen Alma Mater Norfolk State, 2004 Alma Mater Northwestern State, 2007 Assistant AD for Compliance Tiffani-Dawn Sykes Linebackers/Special Teams Coordinator -

We Become Champions by Investing in the Community

Athletic Administration Lonza Hardy Jr. DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS Lonza Hardy Jr. was named Director of Athletics at Hampton University on June 20, 2007, after spending the previous six years in the same capacity at Mississippi Valley State University. A 1978 graduate of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill School of Journalism, Hardy has enjoyed a successful career in college sports for more than 30 years. During his stint at Mississippi Valley State, Hardy worked to elevate the school’s dormant athletics program into a power in the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC). During his six-year reign, the university captured more league championships than it had in the previous 33 years combined. Accordingly, Hardy was awarded the 2006 General Neyland Outstanding Athletics Director Award by the All-American Football Foundation. While at Mississippi Valley State, Hardy created a Student-Athlete Academic Resource Center and the Ashley Ambrose Lounge – which was made possible by a donation from the MVSU alum and Kansas City Chiefs star. Hardy also oversaw the addition of lights and new fencing to the MVSU baseball field, the relocation of the Department of Athletics to better offices on campus, improvements to the press box at Rice-Totten Stadium and improvements to the relocated weight room. Hardy’s efforts also extended to the completion of an on-campus soccer facility and the development of a long-range plan for the construction of an 18-hole golf course and a health and wellness complex, which will house a new basketball arena. Prior to his tenure at Mississippi Valley State, Hardy served as associate commissioner of the SWAC for more than 11 years (1989-2001), where he helped elevate the image of the 10-member league, while handling the conference’s public relations efforts and working hand-in-hand with the commissioner in managing the day-to-day operations of the conference headquarters. -

Livingstone Facing Possible Forfeits

2B SPORTS/The Charlotte Post Thursday, October 23, 1997 Fob the Week of Octobeh 21 through October 27, 1997 BLACK COLLEGE FOOTBALL (Results, Standings and Weekly Honors) OI A ^ Southern Intercollegiate INDEPENDENTS SCORES CIAA MEAC Athletic Conference SWAC Alabama A&M 33. Ft.Valley St, 26, CONF CONF W OT W L T W L T W L W L T W L W. Va. Stale 4 Alabama St. 56, Prairie View A&M 7 Livingstone 8 0 Hampton 3 0 Albany State Southern Benedict 2 Ark.-Pine Bluff 22, Grambling St.16 NC Centra! 3 5 SC State 2 0 Fort Valley Aik. Pine Bluff Langston 1 Bowie State 20, N.C. Central 14 Virginia State 4 2 NCA&T 2 1 Alabama A&M Jackson State Tennessee State 1 Texas Southern Fayetteville State 30, J. C. Smith 27 Virginia Union 3 4 Florida A&M 2 2 Tuskegee Cheyney 0 Delaware State 1 1 Miles Alcorn State Lane 0 Florida A&M 49, Delaware State 0 Fayetteville St. 3 5 Bowie State 4 3 Howard 1 2 Morris Brown Grambling Hampton 9, Norfolk State 2 WSSU 3 4 Morgan State 1 2 Kentucky St. Alabama State BCSP PUYERS OF THE WEEK Howard 52, Morehouse 0 JC Smith 2 5 Bethune-Cookman 0 4 Clark Atlanta Miss. Valley CFFENSE Liberty 16, Virginia Union 0 Elizabeth City 2 5 •Norfolk State 0 0 Savannah St. Prairie View IMARI RAYSOR, (QB) - Lane - Livingstone 41, Elizabeth City 16 ‘Not eligible for championship Morehouse Completed 7 of 11 passes for 115 Miss. Valley State 17, Lane 14 CIAA PLAYERS OF THE WEEK SWAC PLAYERS OF THE WEEK yards and two TDs (9 and 50 yards) Morehead State 56, Miles 41 OFFENSE MEAC PLAYERS OF THE WEEK SIAC PUYERS OF THE WEEK OFFENSE before having to leave the game Morris Brown 7, Benedict 6 WILMONT PERRY, Jr. -

Legends 2018 Program Booklet

Grambling Legends Sports Hall of Fame TRACK | 2018 INDUCTEE Janice Bernard-Forde presented by Alice Jackson (Atlanta) Janice grew up in the small town of Tunapuna Trinidad with her parents Inez and Elias. At an early age, Janice expressed a passion for track and field. She often attended track meets to see other athletes compete. Sister Ruth Palmer, a principal at St. Charles Girls Catholic High School, observed her enthusiasm and encouraged her to join the team. Shortly after doing so, she became one of the top sprinters and received the Athlete of the Year Award from St. Charles. Receiving a track scholarship to attend Grambling State University, she settled in at Grambling and quickly adapted to the culture. While at GSU, she learned the importance of time management and being a team player to achieve her academic and athletic goals. While at Grambling, Janice ran the 60, 100, 200 meters and was on the sprint relay teams. She worked hard to remain focused to complete Coach Ed Stevens’ challenging workouts. She became one of GSU’s top sprinters. Janice was a member of the phenomenal team which competed in collegiate-division track meets, as well as the SWAC Championships. Janice’s dedication to excel landed her a position on the relay team during the Pan American, Caribbean, Commonwealth, and Central American Games. Furthermore, she competed internationally in Ghana, Australia, Cuba, Colombia and Germany. She won medals for her country, broke national records while improving her personal best times. Janice’s career in track and field culminated with representing Trinidad in 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympic Games where she ran the 400 Meter Relay. -

Rattlerfootball

FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY / RATTLERS / FOOTBALL Rattler Football * 12 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS * 130 ALL-AMERICANS * 42 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS * GAME 10 2018 SCORECARD FLORIDA A&M @ S.C. STATE FLORIDA A&M (6-3, 5-1 MEAC) SEPT. 1 FORT VALLEY STATE W, 41-7 SATURDAY, NOV. 10, 2018 / 4PM ET / TALLAHASSEE, FL Jake Gaither Classic * Sports Hall of Fame Game Sept. 8 @ Troy (Ala.) University L, 7-59 BRAGG MEMORIAL STADIUM (25,500) SEPT. 15 JACKSON STATE L,16-18 TV: ESPN 3//LIVE STATS 1978 NCAA Championship Team 40th Anniversary Play-By-Play: Tiffany Greene. Analyst: Alfonso Barber SEPT. 22 *SAVANNAH STATE W, 31-13 1998 Black College National Champs 20th Anniversary LIVE STATS: HBCULiveStats.com/famu/football Sept. 29 * @North Carolina Central (4:00) RADIO: RATLER SPORTS NETWORK OCT. 6 *NORFOLK STATE W, 17-0 Play-By-Play: Keith Miles. Analyst: Albert Chester, Sr. Homecoming Game 96.1 FM Tallahassee, FL Oct. 13 *@North Carolina A&T W, 22-21 OCT. 27 *MORGAN STATE W, 38-3 FLORIDA A&M AT A GLANCE 1988 MEAC Championship 30th Anniversary 2018 Record: 6-3 KEY RATTLERS TO WATCH Nov. 3 *@Howard University L,23-31 MEAC Record: 5-1 RUSHING: RB Deshawn Smith NOV. 10 * S.C.STATE (4:00) Rankings: #3 HBCU (Boxtorow) 502 yards, 82 carries, 2 TDs Head Coach: Willie Simmons PASSING: QB Ryan Stanley, 1,980 yards, Nov. 17 *#Bethune-Cookman (2:00)% Alma Mater: Clemson, 2003 (159 of 265), 15 TDs, 8 INT RECEIVING: WR Chad Hunter HOME GAMES IN BOLD Record at FAMU: 6-3, First Year *Conference Games; @Away games; 40 rec, 518 yards, 6 TDs Career Record: 28-14, 4 Years #Florida Blue Classic at Orlando, FL DEFENSE: LB Elijah Richardson, %-TV ESPNClassic/ESPN3/ESPNU; Last Game: Howard 31, FAMU 23 68 tackles (34 solo), 9.5 TFL, 1 Sack.