Diamonds Have Been Found in Placers in North America Derived from Unknown Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compilation, References, Kimberlite, Diamond

Ontario Geological Survey Open File Report 6067 A Compilation of References for Kimberlite, Diamond and Related Topics 2001 ONTARIO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open File Report 6067 A Compilation of References for Kimberlite, Diamond and Related Topics by R.P. Sage and T. Gareau 2001 Parts of this publication may be quoted if credit is given. It is recommended that reference to this publication be made in the following form: Sage, R.P.and Gareau, T.2001. A compilation of references for kimberlite, diamond and related topics; Ontario Geological Survey, Open File Report 6067, 101p. e Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2001 e Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2001. Open File Reports of the Ontario Geological Survey are available for viewing at the Mines Library in Sudbury, at the Mines and Minerals Information Centre in Toronto, and at the regional Mines and Minerals office whose district includes the area covered by the report (see below). Copies can be purchased at Publication Sales and the office whose district includes the area covered by the report. Al- though a particular report may not be in stock at locations other than the Publication Sales office in Sudbury, they can generally be obtained within 3 working days. All telephone, fax, mail and e-mail orders should be directed to the Publica- tion Sales office in Sudbury. Use of VISA or MasterCard ensures the fastest possible service. Cheques or money orders should be made payable to the Minister of Finance. Mines and Minerals Information Centre (MMIC) Tel: (416) 314-3800 Macdonald Block, Room M2-17 1-800-665-4480(toll free inside Ontario) 900 Bay St. -

Gemstones by Donald W

GEMSTONES By Donald W. olson Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Nicholas A. Muniz, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. In this report, the terms “gem” and “gemstone” mean any gemstones and on the cutting and polishing of large diamond mineral or organic material (such as amber, pearl, petrified wood, stones. Industry employment is estimated to range from 1,000 to and shell) used for personal adornment, display, or object of art ,500 workers (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1997, p. 1). because it possesses beauty, durability, and rarity. Of more than Most natural gemstone producers in the United states 4,000 mineral species, only about 100 possess all these attributes and are small businesses that are widely dispersed and operate are considered to be gemstones. Silicates other than quartz are the independently. the small producers probably have an average largest group of gemstones; oxides and quartz are the second largest of less than three employees, including those who only work (table 1). Gemstones are subdivided into diamond and colored part time. the number of gemstone mines operating from gemstones, which in this report designates all natural nondiamond year to year fluctuates because the uncertainty associated with gems. In addition, laboratory-created gemstones, cultured pearls, the discovery and marketing of gem-quality minerals makes and gemstone simulants are discussed but are treated separately it difficult to obtain financing for developing and sustaining from natural gemstones (table 2). Trade data in this report are economically viable deposits (U.S. -

Prospecting for Diamonds in Kimberlite January 2014 by W

Prospecting for Diamonds in Kimberlite January 2014 by W. Dan Hausel Kimberlite is just one of several rock types that contain diamond. Even so, only two rock types contain commercial amounts of diamonds—kimberlite and olivine lamproite (as well as placers derived from the erosion of these rock types). Commercial amounts of diamonds will likely be discovered in other rock types in the future. These were discussed in a 1998 book, Diamonds and Mantle Source Rocks in the Wyoming Craton with a Discussion of Other US Occurrences, and a 2002 book entitled, Diamond Deposits. Both books can be found by searching the author’s name on Amazon. To date, diamonds have been found in many states in the US—notably Arkansas, California, Colorado, Wyoming and Michigan. Most people assume kimberlite was discovered in South Africa, where it received its namesake at the diamond mines of Kimberley. Search either Google Earth or Flash Earth for “Big Hole Kimberley, South Africa” to see the original mine and also look three to five miles to the southeast at the famous Bulfontein, DuToitspan and Wesselton diamond mines. After you learn a little about the characteristics of kimberlite pipes, you will want to revisit the region around Kimberley because there are anomalies that are likely unmined and possibly undiscovered kimberlites. Kimberlite was actually discovered in the US in the Ithaca, Manheim and Syracuse regions of New York in 1837 where it was described as mica peridotite. Years later, kimberlite was found in Kentucky in 1884 in the chigger infested areas of Ison Creek and Hamilton Branch, two years prior to mica peridotite at Kimberley, South Africa being branded “kimberlite” by Carvil Lewis. -

Rail Tie Wind Project DRAFT Environmental Impact Statement

Rail Tie Wind Project DRAFT Environmental Impact Statement DOE/EIS-0543 March 2021 Cover photograph adapted from the Visual Impact Assessment, Rail Tie Wind Project, Albany County, Wyoming (Tetra Tech 2020a). This photograph depicts the Rail Tie Wind Project Area as viewed toward the southeast from Tie Siding, Wyoming. Vestas V162-5.6 MW wind turbines have been simulated on the landscape as proposed by ConnectGen Albany County LLC. These turbines have a hub height of 410 feet, a blade diameter of 531 feet, and a total turbine height of 675 feet. The nearest turbine pictured is at a distance of approximately 1.25 miles. Draft Environmental Impact Statement Rail Tie Wind Project DOE/EIS-0543 U.S. Department of Energy—Western Area Power Administration ConnectGen Albany County, LLC March 2021 MISSION STATEMENT Safely provide reliable, cost-based hydropower and transmission to our customers and the communities we serve. RAIL TIE WIND PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Western Area Power Administration 12155 W. Alameda Parkway Lakewood, Colorado 80228 DOE/EIS-0543 December 2020 Lead Agency: Western Area Power Administration Type of Action: ( ) Administrative Draft (X) Draft ( ) Final Cooperating Agencies: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 8 Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office Wyoming Office of Governor Mark Gordan Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality Wyoming Office of State Lands and Investments Wyoming Game and Fish Department Authorized Officers Responsible for the Environmental Impact Statement: Contact, Title: Tracey LeBeau, interim Administrator and Chief Executive Officer WAPA Headquarters 12155 W. Alameda Parkway Lakewood, Colorado 80228 720-962-7077 For Further Information, Contact: Mark Wieringa, Document Manager WAPA Headquarters 12155 W. -

Mineral Commodity Summaries 2002--Gemstones

68 GEMSTONES1 (Data in million dollars, unless otherwise noted) Domestic Production and Use: Total U.S. gemstone output has decreased in recent years owing to a decline in foreign demand for freshwater shell, a major component of the domestic industry. Domestic gemstone production included agates, amber, beryl, coral, garnet, jade, jasper, opal, pearl, quartz, sapphire, shell, topaz, tourmaline, turquoise, and many other gem materials. Output of natural gemstones was primarily from Tennessee, Arizona, California, Oregon, Utah, Nevada, and Idaho, in decreasing order. Reported output of synthetic gemstones was from five firms in North Carolina, New York, Florida, California, and Arizona, in decreasing order of production. Major uses were jewelry, carvings, and gem and mineral collections. Salient Statistics—United States: 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001e Production:2 Natural3 25.0 14.3 16.1 17.2 15.3 Synthetic 21.6 24.2 47.5 37.1 24.5 Imports for consumption 8,380 9,250 10,700 12,900 11,700 Exports, including reexports4 2,760 2,980 3,610 4,540 4,590 Consumption, apparent5 5,670 6,310 7,150 8,410 7,190 Price Variable, depending on size, type, and quality Employment, mine, numbere 1,200 1,200 1,200 1,200 1,200 Net import reliance6 as a percentage of apparent consumption 99 99 99 99 99 Recycling: Insignificant. Import Sources (1997-2000): Israel, 40%; India, 21%; Belgium, 20%; and other, 19%. Diamond imports accounted for 93% of the total value of gem imports. Tariff: Item Number Normal Trade Relations 12/31/01 Diamonds, unworked or sawn 7102.31.0000 Free. -

DIAMONDS and MANTLE SOURCE ROCKS in the WYOMING CRATON with a DISCUSSION of OTHER U.S. OCCURRENCES by W

WYOMING STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gary B. Glass, State Geologist DIAMONDS AND MANTLE SOURCE ROCKS IN THE WYOMING CRATON WITH A DISCUSSION OF OTHER U.S. OCCURRENCES by W. Dan Hause} Report of Investigations No. 53 1998 Laramie, Wyoming WYOMING STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Lance Cook, State Geologist GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BOARD Ex Officio Jim Geringer, Governor Randi S. Martinsen, University of Wyoming Don J. Likwartz, Oil and Gas Supervisor Lance Cook, State Geologist Appointed Nancy M. Doelger, Casper Charles M. Love, Rock Springs Ronald A. Baugh, Casper Stephen L. Payne, Casper John E. Trummel, Gillette Computer Services Unit Publications Section Susan McClendon - Manager Richard W. Jones - Editor Jaime R. Bogaard - Editorial Assistant Geologic Sections Lisa J. Alexander - Sales Manager James c. Case, Staff Geologist - Geologic Hazards Fred H . Porter, III - Cartographer Rodney H . De Bruin, Staff Geologist - Oil and Gas Phyllis A. Ranz - Cartographer Ray E. Harris, Staff Geologist - Industrial Minerals Joseph M. Huss - GIS Specialist and Uranium W. Dan Hausel, Senior Economic Geologist - Metals and Precious Stones Supportive Services Unit Robert M. Lyman, Staff Geologist - Coal Susanne G. Bruhnke - Office Manager Alan J. Ver Ploeg, Senior Staff Geologist - Geologic Joan E. Binder - Administrative Assistant Mapping This and other publications available from: Wyoming State Geological Survey P.O. Box 3008 Laramie, WY 82071-3008 Phone: (307) 766-2286 Fax: (307) 766-2605 Email: [email protected] Web Page: http://wsgsweb.uwyo.edu People with disabilities who require an alternative form of communication in order to use this publication should contact the Editor, Wyoming State Geological Survey at (307) 766-2286. TTY Relay operator 1(800) 877-9975. -

Colorado Economic Chronicle Will Be Published Via the in Ternet Only

Legislative Council Colorado Denver, Colorado Tom Dunn Economic Chief Economist Natalie Mullis Chronicle Economist Mike Mauer A Research Newsletter Economist No vem ber 10, 1999 Effective with the January 2000 issue, the Colorado Economic Chronicle will be published via the In ternet only. You can be notified when the latest Chronicle is available by sending your e-mail address to [email protected] with the message “Please notify me when the Chronicle is published.” Because the Chronicle is currently sent to you via bulk mail, you will receive the latest economic news on a more timely basis via the Internet publication of the Colorado Economic Chronicle. Na tional Econ omy F ueled by strong consumer spending, inflation- was 3.1% before the change, and 3.5% after the adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a change. As a result of this revision, second quarter robust pace of 4.8% during the third quarter of 1999, growth increased from 1.6% to 1.9%, first quarter the fastest growth since the fourth quarter of 1998, growth decreased from 4.3% to 3.7%, and 1998 when GDP surged 5.9%. Consumer spending grew growth increased from 3.9% to 4.3%. Second, 4.3% in the third quarter, slightly slower than its government employee retirement plans and gift/estate second quarter growth rate of 5.1%. Businesses taxes will now be counted as personal savings rather increased their inventories by $14.1 billion during the than government savings. Although GDP and national third quarter, helping fuel strong growth. -

Trapping Mechanism for Natural Gas in Jonah Field Jackson Hole

�� ���� �� �� �� � � � � � � ���� � In this issue: � �� ������ �� Trapping mechanism for natural gas Wyoming State Geological Survey in Jonah Field Lance Cook, State Geologist Laramie, Wyoming Jackson Hole Seismic Network at risk October, 2001 Wyoming Geo-notes October, 2001 Featured Articles Overview: Trapping mechanism for natural gas in Jonah Field . 1 Geologic hazards update: Jackson Hole Seismic Network at risk . 30 Contents Minerals update ...................................................... 1 Geologic hazards update: Jackson Hole Overview............................................................... 1 Seismic Network at risk .................................30 Oil and gas update............................................... 3 Publications update .............................................. 31 Coal update......................................................... 12 New publications available from the Coalbed methane update.................................. 17 Wyoming State Geological Survey ............... 31 Industrial minerals and uranium update....... 19 Staff profile.......................................................... 32 Metals and precious stones update ................. 22 Ordering information ........................................ 35 Rock hound’s corner: Garnet............................ 24 Location maps of the Wyoming State Mapping and hazards update.............................. 27 Geological Survey ........................................... 36 Geologic mapping, paleontology, and Improved telephone system -

Diamonds & Mantle Source Rocks in the Wyoming Craton

2007 Diamonds & Mantle Source Rocks in the Wyoming Craton (with discussions on the North American Craton & unconventional source terrains) W. Dan Hausel W. Dan Hausel Geological Consulting LLC 7/30/2007 Abstract Many diamonds found in the United States were derived from known host rocks (e.g., kimberlite and lamproite). The distribution of the known diamondiferous host rocks as well as the associated basement terrane indicates that the greatest potential for the discovery of commercial diamond deposits in the U.S. lies within the Wyoming craton. To date, more than 100 kimberlites, one of the largest lamproite fields in the world, and more than 130,000 diamonds, have been found along the margin of this craton. Several secondary diamond occurrences have also been found in the United States. Many of these may have been derived from undiscovered kimberlites and lamproites; however, the hundreds of diamonds reported in the Pacific Coast region lie in an area considered to be unfavorable for kimberlite and lamproite. It is possible that many of these diamonds originated from unconventional host rocks. Introduction Diamonds have been found in the United States ranging from small crystals less than 1 carat to thumbnail-size crystals weighing up to 40 carats. The source of many of these diamonds has remained a mystery; however, with the relatively recent identification of several diamondiferous host rock sources, one can deduce that many of these diamonds were derived from the erosion of yet-undiscovered ultramafic to mafic host rocks. Potential host rocks have now been identified in many states within the U.S. -

Chapter 5: Mineral Resources of the Southwestern US

Chapter 5: Mineral Resources of the granite • a common and Southwestern US widely occurring type of igneous rock. What is a mineral? A mineral is a naturally occurring inorganic solid with a specific chemical igneous rocks • rocks derived composition and a well-developed crystalline structure. Minerals provide the from the cooling of magma foundation of our everyday world. Not only do they make up the rocks we see underground or molten lava on around us in the Southwest, they are also used in nearly every aspect of our the Earth’s surface. lives. The minerals found in the rocks of the Southwest are used in industry, construction, machinery, technology, food, makeup, jewelry, and even the paper on which these words are printed. mica • a large group of sheetlike silicate minerals. Minerals provide the building blocks for rocks. For example, granite, an igneous rock, is typically made up of crystals of the minerals feldspar, quartz, mica, and amphibole. In contrast, sandstone may be made of cemented grains of feldspar, quartz, and mica. The minerals and the bonds between the amphibole • a group of dark crystals define a rock's color and resistance to weathering. colored silicate minerals, or either igneous or metamorphic Several thousand minerals have been discovered and classified according origin. to their chemical composition. Most of them are silicates (representing approximately a thousand different minerals, of which quartz and feldspar are two of the most common and familiar), which are made of silicon and oxygen sandstone • sedimentary rock combined with other elements (with the exception of quartz, SiO2). Carbonate formed by cementing together rocks are made of carbon and oxygen combined with a metallic element; grains of sand. -

429-GIA-Monograph-Unclesam-Draft2

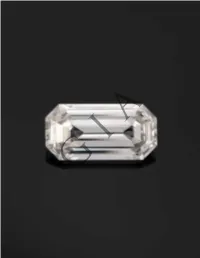

A I G GIA Monograph | The Uncle Sam Diamond The Uncle Sam Diamond Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 1 A The Uncle Sam Diamond and the Crater of Diamonds State Park ........................................................................ 2 Provenance of the Uncle Sam Diamond ....................................................................................................................... 4 I Occurrences & Geographic Origins of Diamonds .................................................................................................... 6 Diamond Formation & Geology ................................................................................................................................ 12 G Manufacture of the Uncle Sam Diamond .................................................................................................................. 14 A System for Grading Diamond Color ....................................................................................................................... 16 Gemological Examination ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Advanced Analytical Techniques ................................................................................................................................ 18 Summary .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Patriot Diamonds to Give Mining in Larimer County a New Spark

Format Dynamics :: CleanPrint :: http://www.coloradoan.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=2011107310327 8/10/11 3:42 PM Exploration for diamonds has a long and Patriot Diamonds to fitful history in Larimer County, where Superior Oil, Cominco, DiamonEx and other give mining in companies have searched and mined for diamonds in spurts over the last 50 years. Larimer County a DiamonEx's Kelsey Lake diamond mine opened in northern Larimer County in the new spark late-1990s, but shuttered after only a few years of operation. Most of the county's kimberlite deposits Written by have been explored thoroughly, but only Bobby Magill the deposit at Kelsey Lake ever proved [email protected] financially viable for mining, Kelsey Lake 11:15 PM, Jul. 30, 2011| diamond prospector Howard Coopersmith said in 2009. Mining for home-grown, or "patriot," diamonds in Larimer County may soon get Coopersmith, of Fort Collins, was a a new spark of life. consultant for North American Minerals, a now-defunct company based in New York Roosevelt National Forest officials are City and Calgary that had planned to mine considering Calgary, Alberta-based Patriot for kimberlite on four parcels of land in Diamonds, Inc.'s proposal to drill for Roosevelt National Forest. diamond-containing kimberlite deposits at 11 sites in the Chicken Park area of North American Minerals' marketing northern Larimer County. strategy was simple, company operator Yosi Lapid said in 2009: "Buy American - The company wants to drill for the material without building new roads or processing Advertisement the kimberlite on the site, which is north of Red Feather Lakes and south of the North Fork of the Poudre River.