'Tfte Jfuntsvicce Jfistoricac (Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

The True Mary Todd Lincoln ALSO by BETTY BOLES ELLISON

The True Mary Todd Lincoln ALSO BY BETTY BOLES ELLISON The Early Laps of Stock Car Racing: A History of the Sport and Business through 1974 (McFarland, 2014) The True Mary Todd Lincoln A Biography BETTY BOLES ELLISON McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Ellison, Betty Boles. The true Mary Todd Lincoln : a biography / Betty Boles Ellison. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-7836-1 (softcover : acid free paper) ♾ ISBN 978-1-4766-1517-2 (ebook) 1. Lincoln, Mary Todd, 1818–1882. 2. Presidents’ spouses—United States— Biography. 3. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809–1865—Family. I. Title. E457.25.L55E45 2014 973.7092—dc23 [B] 2014003651 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2014 Betty Boles Ellison. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: Oil portrait of a twenty-year-old Mary Todd painted in 1928 by Katherine Helm, a niece of Mary Todd Lincoln and daughter of Confederate General Ben H. Helm. It is based on a daguerreotype taken in Springfield by N.H. Shepherd in 1846; a companion daguerreotype is the earliest known photograph of Lincoln (courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum of Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, Tennessee) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com For Sofia E. -

Copyright by CLP Research 1600 1700 1750 1800 1850 1650 1900 Partial Genealogy of the Todds, Part II 2 Main Political Affiliatio

Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Todds, Part II Main Political Affiliation: (of Kentucky & South Dakota) 1763-83 Whig/Revolutionary 1789-1823 Republican 1824-33 National Republican 1600 1834-53 Whig 1854- Republican 2 1650 John Todd (1667-1719) (born Ellerlise, Lanarkshire, Scotland); (moved to Drumgare, Derrymore Parish, County Armagh, Ireland) = Rose Cornell (1670s?-at least 1697 Samuel Todd 3 Others Robert Todd William Todd (1697-1760)) (1697-1775) (1698-1769) (Emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland to Pennsylvania, 1732) (Emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland to Pennsylvania, 1732) = Jean Lowe 1700 (moved to Virginia) Ann Smith = = Isabella Bodley Hamilton (1701-at least 1740) See Houston of NC = Ann Houston (1697-1724) (1697-1739) Genealogy (1698-at least 1736) 1 Son David Todd 9 Children 5 Others Sarah Todd (1723-85); (farmer) 6 Others Lydia Todd (1727-95) (Emigrated from Ireland with father); (moved to Kentucky to join sons, 1784) (1736-1812) = John Houston III = Hannah Owen = James M. McKee (1727-98) (1720-1805) (1726-78) (moved to Tennessee) See McKee of KY See Houston of NC 5 Others Lt. Levi Todd Genealogy 1750 Genealogy (1756-1807); (lawyer) (born Pennsylvania); (moved to Kentucky, 1776); ((Rev War with Gen. George Rogers Clark/Kaskaskia) (clerk, KY district court, controlled by Virginia, 1779; of Fayette co. KY, part of VA, 1780-1807 Jane Briggs = = Jane Holmes (1761-1800) (1779-1856) Dr. John Todd I 8 Others Robert Smith Todd 1 Son (1787-1865) (1791-1849) (born Kentucky); (War of 1812) (clerk, KY house, 1821-41); (president, Bank of Kentucky, Lexington branch) (moved to Illinois) (KY house, 1842-44); (KY senate, 1845-49) 1800 = Elizabeth Fisher Smith of PA Eliza Ann Parker = = Elizabeth Humphreys (1793-1865) (1794-1825) (1801-74) 5 Others Gen. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

Spider-Woman

DC MARVEL IMAGE ! ACTION ! ALIEN ! ASCENDER ! AMERICAN VAMPIRE 1976 ! AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ! BIRTHRIGHT ! AQUAMAN ! AVENGERS ! BITTER ROOT ! BATGIRL ! AVENGERS: MECH STRIKE 1-5 ! BLISS 1-8 ! BATMAN ! BETA RAY BILL 1-5 ! COMMANDERS IN CRISIS 1-12 ! BATMAN ADVENTURES CONTINUE ! BLACK CAT ! CROSSOVER ! BATMAN BLACK & WHITE 1-6 ! BLACK KNIGHT CURSE EBONY BLADE ! DEADLY CLASS ! BATMAN: URBAN LEGENDS ! BLACK WIDOW ! DECORUM ! BATMAN/CATWOMAN 1-12 ! CABLE ! DEEP BEYOND ! BATMAN/SUPERMAN ! CAPTAIN AMERICA ! DEPARTMENT OF TRUTH ! CATWOMAN ! CAPTAIN MARVEL ! EXCELLENCE ! CRIME SYNDICATE ! CARNAGE BW & BLOOD 1-4 ! FAMILY TREE ! DETECTIVE COMICS ! CHAMPIONS ! FIRE POWER ! DREAMING : WAKING HOURS ! CHILDREN OF THE ATOM ! GEIGER ! FAR SECTOR ! CONAN THE BARBARIAN ! ICE CREAM MAN ! FLASH ! DAREDEVIL ! JUPITERS LEGACY 1-5 ! GREEN ARROW ! DEADPOOL ! KARMEN 1-5 ! GREEN LANTERN ! DEMON DAYS X-MEN 1-5 ! KILLADELPHIA ! HARLEY QUINN ! ETERNALS ! LOW ! INFINITE FRONTIER ! EXCALIBUR ! MONSTRESS ! JOKER ! FANTASTIC 4 ! MOONSHINE ! JUSTICE LEAGUE ! FANTASTIC 4 LIFE STORY 1-6 ! NOCTERRA ! LAST GOD ! GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY ! OBLIVION SONG ! LEGENDS OF DARK KNIGHT ! HELLIONS ! OLD GUARD 1-6 ! LEGION of SUPER-HEROES ! HEROES REBORN 1-7 ! POST AMERICANA 1-6 ! MAN-BAT ! IMMORTAL HULK ! RADIANT BLACK ! NEXT BATMAN: SECOND SON ! IRON FIST Heart of Dragon 1-6 ! RAT QUEENS ! NIGHTWING ! IRON MAN ! REDNECK ! OTHER HISTORY DC UNIVERSE ! MAESTRO WAR & PAX 1-5 ! SAVAGE DRAGON ! RED HOOD ! MAGNIFICENT MS MARVEL ! SEA OF STARS ! RORSCHACH ! MARAUDERS ! SILVER COIN 1-5 ! SENSATIONAL -

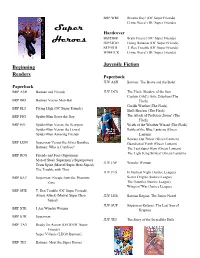

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Lincoln Lore

Lincoln Lore Bulletin of the Louia A. Warren l...incoln Library and Museum. Mark E. Neely, Jr., Editor. Published September, 1977 each month by the Lincoln Notional Ufe Lnaunnce Company, Fort Wayne. Indiana 46801. Number 1675 TWO NEW LINCOLN SITES ... MAYBE America's continuing interest in Abraham Lincoln is a rJiinois as well. A new site in Kentuckywasdedicatedjustthis phenomenon most evident on a broadly popular level. There yea.r, and people in Vennont, ofall places, are at work to save may well be less research in progress on Lincoln manuscripts another Lincoln-related historical site. and books than there was two or three decades ago. Real ac· The newest addition is the Mary Todd Lincoln House in tion is taking place, however, where masses of Americans Lexinl[ton, Kentucky. dedicated on June ninth of this year. look increasingly for their contacts with history, at historical Like all such events, this dedication was the result of con sites. T he National Park Service initiated a long-range pro siderable struggle over a substantial period in the past. More gram to improve the Lincoln homesite in Springfield, illinois, than seven years ago, Mrs. Louis B. Nunn. wife of t.hegover· some years back. There is a large project under way to up nor of Kentucky at that time, visited the historic brick house grade the interpretative material at other Lincoln s ites in in which Mary Todd spent her girlhood years. The wives of the J'ro rn th.~ l..t>tu ll A. WarrM l.mroln l.1 brar;y and Mu.f('Um FIGURE I. -

Subscription Pamplet New 11 01 18

Add More Titles Below: Vault # CONTINUED... [ ] Aphrodite V [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Auntie Agatha's Wayward Bunnies (6) [ ] James Bond [ ] Bitter Root [ ] Lone Ranger [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Blackbird [ ] Mars Attack [ ] Bully Wars [ ] Miss Fury [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Burnouts [ ] Project SuperPowers 625 N. Moore Ave., [ ] Cemetery Beach (of 7) [ ] Rainbow Brite [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cold Spots (of 5) [ ] Red Sonja Moore OK 73160 [ ] Criminal [ ] Thunderbolt [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Crowded [ ] Turok [ ] Curse Words [ ] Vampirella Dejah Thores [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cyber Force [ ] Vampirella Reanimator Subscription [ ] Dead Rabbit [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Die Comic Pull Sheet [ ] East of West [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Errand Boys (of 5) [ ] Evolution [ ] ___________________________ We offer subscription discounts for [ ] Exorisiters [ ] Freeze [ ] Adventure Time Season 11 [ ] ___________________________ customers who want to reserve that special [ ] Gideon Falls [ ] Avant-Guards (of 12) comic book series with SUPERHERO [ ] Gunning for Hits [ ] Black Badge [ ] ___________________________ BENEFITS: [ ] Hardcore [ ] Bone Parish [ ] Hit-Girl [ ] Buffy Vampire Slayer [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Ice Cream Man [ ] Empty Man Tier 1: 1-15 Monthly ongoing titles: [ ] Infinite Dark [ ] Firefly [ ] ___________________________ 10% Off Cover Price. [ ] Jook Joint (of 5) [ ] Giant Days [ ] Kick-Ass [ ] Go Go Power Rangers [ ] ___________________________ -

13 Superhero Passages

13 Informational Text Passages w/TDQs Can be used in centers, for Close Reading for ELA Assessments, or will make up to 13 weeks of homework. Text Evidence Practice! Aligned to CCSS Teacher’s Guide Thank you so much for purchasing! Background: Citing text evidence is a difficult task for many students. Children are inclined by nature to use their background knowledge. This packet will help students to maintain integrity to “Cite the Evidence”. You will find the structural response system known as RACE on pages where it applies. This communicates the manner in which to answer questions. Parents and students understand expectations. Utilizations: This packet can be used during small group time for guided reading and/or close reading. As the teacher, you can have students highlight, code the text, attend to structural analysis, and conduct vocabulary mini-lessons. Students can then revisit the piece for homework. For each passage, you will find two pages of text dependent questions aligned to Common Core standards. This makes it appropriate to use for assessment purposes. Passage borders are corrugated. This makes it easy for you to match up for your files or when creating homework packets. I have the passages duplicated without border. Scroll to the end of the unit or click here. The purpose of the passages without border is so you have room to code text and annotate in the margins. These passages were specifically designed for Close Reading. Examine word choice! Examine functions of words and sentences. I worked VERY HARD on this unit. Please leave kind feedback and respectable ratings.