Honorable Soldiers, Too: an Historical Case Study of Post-Reconstruction African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

African American History at Penn State

Penn State University African American Chronicles February 2010 Table of Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 Years 1899 – 1939 3 Years 1940 – 1949 8 Years 1950 – 1959 13 Years 1960 – 1969 18 Years 1970 – 1979 26 Years 1980 – 1989 35 Years 1990 – 1999 43 Years 2000 – 2008 47 Appendix A – Douglass Association Petition (1967) 56 Appendix B - Douglass Association 12 Demands (1968) 57 Appendix C - African American Student Government Presidents 58 Appendix D - African American Board of Trustee Members 59 Appendix E - First African American Athletes by Sport 60 Appendix F - Black Student Enrollment Chart 61 Appendix G – Davage Report on Racial Discrimination(1958) 62 Appendix H - “It Is Upon Us” Holiday Poem (1939) 63 Penn State University African American Chronicles February 2010 INTRODUCTION “Armed with a knowledge of our past, we can with confidence charter a course for our future.” - Malcolm X Sankofa (sang-ko-fah) is an Akan (Ghana & Ivory Coast) term that literally means, "To go back and get it." One of the symbols for Sankofa (above right) depicts a mythical bird moving forward, but with its head turned backward. The egg in its mouth represents the "gems" or knowledge of the past upon which wisdom is based; it also signifies the generation to come that would benefit from that wisdom. It is hoped that this document will inspire Penn State students, faculty, staff, and alumni to learn from and build on the efforts of those who came before them. Source: Center for Teaching & learning - www.ctl.du.edu In late August, 1979, my twin brother, Darnell and I arrived at Penn State’s University Park campus to begin our college education. -

Reginald Howard

20080618_Howard Page 1 of 14 Dara Chesnutt, Denzel Young, Reginald Howard Dara Chesnutt: Appreciate it. Could you start by saying your full name and occupation? Reginald Howard: Reginald R. Howard. I’m a real estate broker and real estate appraiser. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Where were you born and raised? Reginald Howard: South Bend, Indiana, raised in Indiana, also, born and raised in South Bend. Dara: Where did you grow up and did you move at all or did you stay mostly in –? Reginald Howard: No. I stayed mostly in Indiana. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. What are the names of your parents and their occupations? Reginald Howard: My mother was a housewife and she worked for my father. My father’s name was Adolph and he was a tailor and he had a dry cleaners, so we grew up sorta privileged little black kids. Even though we didn’t have money, people thought we did for some reason. Dara Chesnutt: Did you have any brothers or sisters? Reginald Howard: Sure. Dara Chesnutt: Okay, what are their names and occupations? Reginald Howard: I had a brother named Carlton, who is deceased. [00:01:01] I have a brother named Dean, who’s my youngest brother, who’s just retired from teaching in Tucson, Arizona and I have a sister named Alfreda who’s retired and lives in South Bend still. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Could you talk a little bit about what your home life was like? Reginald Howard: I don’t know. I had a very strong father and very knowledgeable father. We were raised in a predominantly Hungarian-Polish neighborhood and he – again, he had a business and during that era, it was the area of neighborhood concept businesses and so people came to us for service, came to him for the service, and he was well thought of. -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

2000 Vol. 8 No. 1 Cleveland-Marshall College of Law

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Notes Law Publications 2000 2000 Vol. 8 No. 1 Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/ lawpublications_lawnotes Part of the Law Commons How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Recommended Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, "2000 Vol. 8 No. 1" (2000). Law Notes. 39. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/lawpublications_lawnotes/39 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Publications at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Notes by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vo lume 8 • Issue 1 Cleveland-Marshall Law Alumni Association News REMEMBER THE LADIES Our Remarkable First 100 Women Graduates Who We Are We are one of the premier court reporting agencies in the industry. We do not compete with other agencies but join the ranks of those who operate in respect to the profession and in dedication to excellence. We constantly strive to do our best, to revise and refine our professional skills. We do this out of habit. We do this out oflove of the profession. We do this because of the peace and joy that it brings to us and to those around us who share our vision. We do this because it feels good. We work in service to the legal community. We recognize the complex and demanding profession of our clients. We pledge our talents, time and professionalism as vital contributions to the legal profession. -

The Career of Harman Blennerhassett Author(S): J

The Career of Harman Blennerhassett Author(s): J. E. Fuller Source: Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 17 (Oct., 1916), pp. 16-41 Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30059729 Accessed: 27-06-2016 10:59 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Kerry Archaeological Magazine This content downloaded from 130.63.180.147 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:59:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms RESIDENCE OF HARMAN BLENNERHASSETT. This content downloaded from 130.63.180.147 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:59:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Career of Harman Blennerhassett. DO not know that the chequered life of the subject of this memoir has ever been fully chronicled in this country, though exhaustive details can be gleaned from American publications.1 The stor y ought to be of great interest to Kerry- men; for not only was he a scion of "the Kingdom," but related to all the leading families in the county. He J was the younger son of Conway Blenner- . -

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “A CRUSADE AGAINST THE DESPOILER OF VIRTUE”: BLACK WOMEN, SEXUAL PURITY, AND THE GENDERED POLITICS OF THE NEGRO PROBLEM 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the co-direction of Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay And approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY Dissertation Co-Directors: Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 is a study of the activism of slave, poor, working-class and largely uneducated African American women around their sexuality. Drawing on slave narratives, ex-slave interviews, Civil War court-martials, Congressional testimonies, organizational minutes and conference proceedings, A Crusade takes an intersectional and subaltern approach to the era that has received extreme scholarly attention as the early women’s rights movement to understand the concerns of marginalized women around the sexualized topic of virtue. I argue that enslaved and free black women pioneered a women’s rights framework around sexual autonomy and consent through their radical engagement with the traditionally conservative and racially-exclusionary ideals of chastity and female virtue of the Victorian-era. -

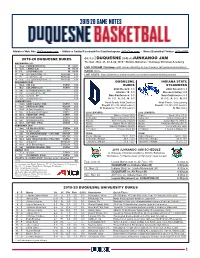

2019-20 Game Notes

2019-20 game notes Athletics Web Site: GoDuquesne.com • Athletics Twitter/Facebook/YouTube/Instagram: @GoDuquesne • Men’s Basketball Twitter: @DuqMBB 2019-20 DUQUESNE DUKES G4, 5, 6 | DUQUESNE (3-0) at JUNKANOO JAM NOVEMBER (3-0) Th.-Sun., Nov. 21, 22 & 24, 2019 • Bimini, Bahamas • Gateway Christian Academy 5 Tues. PRINCETON (PPG) W 94-57 LIVE STREAM: FloHoops with James Westling & Joe Cravens (all games/subscription) 12 Tues. LAMAR (LA) W 66-56 15 Fri. LIPSCOMB (LA) W 58-36 RADIO: None 21 Thur. vs. Indiana State - JJ FloHoops 6:30 LIVE STATS: https://junkanoo.sidearmstats.com/sidearmstats/mbball/summary 22 Fri. vs. Air Force - JJ FloHoops 6:30 24 Sun. vs. Loyola Marymount - JJ FloHoops 6:30 DECEMBER (0-0) DUQUESNE INDIANA STATE 4 Wed. VMI (LA) ESPN+ 7:00 DUKES SYCAMORES 9 Mon. COLUMBIA (LA) ESPN+ 7:00 3-0 0-3 14 Sat. vs. Radford at Akron, Ohio 2:00 2020 Record: 2020 Record: 21 Sat. vs. Austin Peay - SP 2:30 Atlantic 10: 0-0 Missouri Valley: 0-0 22 Sun. vs. UAB - SP 2:30 Non-Conference: 3-0 Non-Conference: 0-3 29 Sun. vs. Marshall - CL 2:30 H: 3-0; A: 0-0; N: 0-0 H: 0-0; A: 0-3; N: 0-0 JANUARY (0-0) Head Coach: Keith Dambrot Head Coach: Greg Lansing 2 Thur. SAINT LOUIS+ (RM) ESPN+ 7:00 Overall: 451-238 (22nd season) Overall: 148-145 (10th season) 5 Sun. DAVIDSON+ (RM) NBCSN 2:00 At Duquesne: 38-29 (3rd season) At ISU: Same 8 Wed. -

The Demise of African American Participation in Baseball: a Cultural Backlash from the Negro Leagues

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln 10th Annual National Conference (2005): People of Color in Predominantly White Different Perspectives on Majority Rules Institutions November 2005 The Demise of African American Participation in Baseball: A Cultural Backlash from the Negro Leagues David C. Ogden Associate Professor, School of Communication, University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/pocpwi10 Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Ogden, David C., "The Demise of African American Participation in Baseball: A Cultural Backlash from the Negro Leagues" (2005). 10th Annual National Conference (2005): Different Perspectives on Majority Rules . 29. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/pocpwi10/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the People of Color in Predominantly White Institutions at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in 10th Annual National Conference (2005): Different Perspectives on Majority Rules by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Demise of African American Participation in Baseball: A Cultural Backlash from the Negro Leagues Abstract Sixty years ago baseball was a major business and cultural force for African Americans. But the end of the Negro Leagues and the desegregation of baseball heralded a new era that marked the beginning of a cultural drift between baseball and African Americans. This paper will explore the social factors embedded in the Negro Leagues that gave baseball cultural relevance for African Americans and what is impeding those factors from operating again. David C. Ogden Associate Professor, School of Communication, University of Nebraska at Omaha In 1942 51,000 spectators, most of them African Americans, filled Comiskey Park in Chicago to see the East-West Game, the Negro Leagues’ version of the major league All- Star Game (Rader, 1994). -

A HISTORY of BELPRE Washington County, Ohio

A HISTORY OF BELPRE Washington County, Ohio -By- C. E. DICKINSON, D. D. Formerly Pastor of Congregational Church Author of the History of the First Congregational Church Marietta, Ohio PUBUIBHID FOR THB AUTHOR BY GLOBE PRINTING & BINDING COMPANY PARKRRSBURG. WEST VIRGINIA Copyrighted in 1920 by C. E. DICKINSON DEDICATED To the Belpre Historical Society with the hope that it will increase its efficiency and keep alive the interest of the people in the prosperity of their own community. FOREWORD The history of a township bears a similar relation to the history of a nation that the biography of an indi vidual bears to the record of human affairs. Occasionally an individual accomplishes a work which becomes an essential and abiding influence in the history of the world. Such persons however are rare, although a considerable number represent events which are important in the minds of relatives and friends. The story of only a few townships represents great historic events, but ac counts of the transactions in many localities are of im portance to the present and future residents of the place. Belpre township is only a small spot on the map of Ohio and a smaller speck on the map of the United* States. Neither is this locality celebrated for the transaction of many events of world-wide importance; at the same time the early history of Belpre exerted an influence on the well being of the State which makes an interesting stqpy for the descendants of the pioneers and other residents of the township. Within a very few months of the arrival of the first settlers at Mariettapfchey began to look for the most favorable places to locate jtheir homes. -

Texas Women in Higher Education Annual Conference April 8-9, 2010 Hilton Dallas Park Cities, Dallas

HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY: LEADING WITH A FEMININE TWIST Texas Women in Higher Education Annual Conference April 8-9, 2010 Hilton Dallas Park Cities, Dallas While registration is open to all who are interested, please note that the topics for the annual conference are designed for women currently serving in leadership positions (chairs, directors, deans, presidents, et al.) at institutions of higher education in Texas. WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7, 2010 6:00 – 8:00 pm TWHE Board Meeting and Dinner THURSDAY, APRIL 8, 2010 9:00 am – 1:30 pm Registration/Check-in at Hilton Dallas Park Cities 9:30 – 11:30 am Preconference Workshops (Optional; choose one; additional fee) 1. Moving On Up: Career Mapping and the Search Process Women leaders in higher education can chart their professional careers and create a competitive edge by understanding the search process. This preconference will feature Donna Phillips, Executive Director of the American Council on Education’s Office of Women in Higher Education, and Bill Funk, President, William R. Funk & Associates, a higher education search firm. The session will have value for leaders engaged in the hiring process at their universities as well as those wishing to be hired. 2. Our Time Has Come: Today’s Women and Their Charitable Giving Women donors are increasingly important to our institutions of higher education. This preconference, featuring university administrators and development leaders, women philanthropists, and fundraising experts, will prepare higher education leaders to carry out fundraising with women philanthropists. Panel presenters include Mary Jalonick, President of the Dallas Foundation; Becky Sykes, President and CEO of the Dallas Women’s Foundation, and Susan Wommack, Gift Planning Legal Counsel, Baylor University. -

Manuscript Collection General Index

as of 05/11/2021 Missouri State Archives RG998 Manuscript Collection General Index MS Collection Title Collection Description Date(s) Coverage Digitized? Notes NO. 1 The Menace Newspaper One 1914 issue of the anti-Catholic The Menace newspaper, 4/25/1914 Nationwide Y PDF on Manuscript DVD #1 in Reference published in Aurora, MO. 2 Governor Sam A. Baker Collection Miscellaneous items relating to the administration of Baker as 1897-1955 Missouri Partially TIFFs and PDFs on Manuscript DVD #1 in Governor of Missouri and various other public offices. Reference 3 May M. Burton U.S. Land Sale May M. Burton land patent certificate from U.S. for land in 4/1/1843 Randolph County Y PDF on Manuscript DVD #1 in Reference Randolph County Missouri dated 1 April 1843. 4 Neosho School Students' Missouri Missouri Sesquicentennial Celebration, 1971. Drawings by 5th 1971 Neosho, Newton Y PDF on Manuscript DVD #1 in Reference Sesquicentennial Birthday Cards grade class, Neosho, Missouri. County 5 Marie Byrum Collection This is a Hannibal, MO Poll Book showing Marie Byrum as the 8/31/1920 Hannibal, Marion Partially PDF on Manuscript DVD #1 in Reference; TIFF first female voter and Harriet Hampton as the first female County on Z Drive African-American in Missouri – and possibly the nation – to cast votes after suffrage. Includes a photograph of Byrum. 6 Edwin William Stephens Collection Scrapbooks and other memorabilia relating to the public career 1913-1931 Missouri Partially Images of the trowel are on Manuscript DVD #1 of Stephens. Includes trowel. Includes Specifications of the in Reference Missouri State Capitol book.