Searching for Reflected Light from Τ Bootis B with High-Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dust Environment and Dynamical History of a Sample of Short-Period Comets II

A&A 571, A64 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424331 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Dust environment and dynamical history of a sample of short-period comets II. 81P/Wild 2 and 103P/Hartley 2 F. J. Pozuelos1;3, F. Moreno1, F. Aceituno1, V. Casanova1, A. Sota1, J. J. López-Moreno1, J. Castellano2, E. Reina2, A. Climent2, A. Fernández2, A. San Segundo2, B. Häusler2, C. González2, D. Rodriguez2, E. Bryssinck2, E. Cortés2, F. A. Rodriguez2, F. Baldris2, F. García2, F. Gómez2, F. Limón2, F. Tifner2, G. Muler2, I. Almendros2, J. A. de los Reyes2, J. A. Henríquez2, J. A. Moreno2, J. Báez2, J. Bel2, J. Camarasa2, J. Curto2, J. F. Hernández2, J. J. González2, J. J. Martín2, J. L. Salto2, J. Lopesino2, J. M. Bosch2, J. M. Ruiz2, J. R. Vidal2, J. Ruiz2, J. Sánchez2, J. Temprano2, J. M. Aymamí2, L. Lahuerta2, L. Montoro2, M. Campas2, M. A. García2, O. Canales2, R. Benavides2, R. Dymock2, R. García2, R. Ligustri2, R. Naves2, S. Lahuerta2, and S. Pastor2 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), Glorieta de la Astronomía s/n, 18008 Granada, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Amateur Association Cometas-Obs, Spain 3 Universidad de Granada-Phd Program in Physics and Mathematics (FisyMat), 18071 Granada, Spain Received 3 June 2014 / Accepted 5 August 2014 ABSTRACT Aims. This paper is a continuation of the first paper in this series, where we presented an extended study of the dust environment of a sample of short-period comets and their dynamical history. On this occasion, we focus on comets 81P/Wild 2 and 103P/Hartley 2, which are of special interest as targets of the spacecraft missions Stardust and EPOXI. -

List of Missions Using SPICE (PDF)

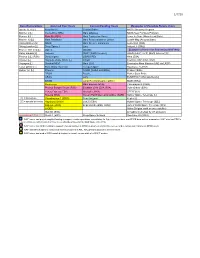

1/7/20 Data Restorations Selected Past Users Current/Pending Users Examples of Possible Future Users Apollo 15, 16 [L] Magellan [L] Cassini Orbiter NASA Discovery Program Mariner 2 [L] Clementine (NRL) Mars Odyssey NASA New Frontiers Program Mariner 9 [L] Mars 96 (RSA) Mars Exploration Rover Lunar IceCube (Moorehead State) Mariner 10 [L] Mars Pathfinder Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter LunaH-Map (Arizona State) Viking Orbiters [L] NEAR Mars Science Laboratory Luna-Glob (RSA) Viking Landers [L] Deep Space 1 Juno Aditya-L1 (ISRO) Pioneer 10/11/12 [L] Galileo MAVEN Examples of Users not Requesting NAIF Help Haley armada [L] Genesis SMAP (Earth Science) GOLD (LASP, UCF) (Earth Science) [L] Phobos 2 [L] (RSA) Deep Impact OSIRIS REx Hera (ESA) Ulysses [L] Huygens Probe (ESA) [L] InSight ExoMars RSP (ESA, RSA) Voyagers [L] Stardust/NExT Mars 2020 Emmirates Mars Mission (UAE via LASP) Lunar Orbiter [L] Mars Global Surveyor Europa Clipper Hayabusa-2 (JAXA) Helios 1,2 [L] Phoenix NISAR (NASA and ISRO) Proba-3 (ESA) EPOXI Psyche Parker Solar Probe GRAIL Lucy EUMETSAT GEO satellites [L] DAWN Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter MOM (ISRO) Messenger Mars Express (ESA) Chandrayan-2 (ISRO) Phobos Sample Return (RSA) ExoMars 2016 (ESA, RSA) Solar Orbiter (ESA) Venus Express (ESA) Akatsuki (JAXA) STEREO [L] Rosetta (ESA) Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KARI) Spitzer Space Telescope [L] [L] = limited use Chandrayaan-1 (ISRO) New Horizons Kepler [L] [S] = special services Hayabusa (JAXA) JUICE (ESA) Hubble Space Telescope [S][L] Kaguya (JAXA) Bepicolombo (ESA, JAXA) James Webb Space Telescope [S][L] LADEE Altius (Belgian earth science satellite) ISO [S] (ESA) Armadillo (CubeSat, by UT at Austin) Last updated: 1/7/20 Smart-1 (ESA) Deep Space Network Spectrum-RG (RSA) NAIF has or had project-supplied funding to support mission operations, consultation for flight team members, and SPICE data archive preparation. -

EPOXI COMET ENCOUNTER FACT SHEET Nov

EPOXI COMET ENCOUNTER FACT SHEET Nov. 2, 2010 Quick Facts Flyby Spacecraft Dimensions: 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) long, 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) wide, and 2.3 meters (7.5 feet) high Weight: 601 kilograms (1,325 pounds) at launch, consisting of 517 kilograms (1,140 pounds) spacecraft and 84 kilograms (185 pounds) fuel. On 10/25/10 there was 4 kilograms (8.8 pounds) of fuel remaining. Power: 2.8-meter-by-2.8-meter (9-foot-by-9 foot) solar panel providing up to 750 watts, depending on distance from sun. Power storage via small, 16-amp- hourrechargeable nickel hydrogen battery Comet Hartley 2 Nucleus shape: Elongated Nucleus size (estimated): About 2.2 kilometers (1.4 miles) long Nucleus mass: Roughly 280 million metric tons Nucleus rotation period: About 18 hours Nucleus composition: Water ice, carbon dioxide ice, silicate dust Mission Launch: Jan. 12, 2005 Launch site: Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida Launch vehicle: Delta II 7925 with Star 48 upper stage Impact with Tempel 1: 10:52 p.m. PDT July 3, 2005 (1:52 a.m. EDT July 4, 2005) Earth-comet distance at time of impact: 133.6 million kilometers (83 million miles) Total distance traveled by spacecraft from Earth to Tempel 1: 431 million kilometers (268 million miles) Flyby of Hartley 2: About 10 a.m. EDT or 7 a.m. PDT Nov. 4, 2010 Additional distance traveled by spacecraft to Hartley 2: About 4.6 billion kilometers (2.9 billion miles) Program Cost of Deep Impact: $267 million total (not including launch vehicle), consisting of $252 million spacecraft development and $15 million mission operations Cost of EPOXI extended mission: $42 million, for operations from 2007 to end of project at the end of fiscal year 2011. -

Planetary Science

Mission Directorate: Science Theme: Planetary Science Theme Overview Planetary Science is a grand human enterprise that seeks to discover the nature and origin of the celestial bodies among which we live, and to explore whether life exists beyond Earth. The scientific imperative for Planetary Science, the quest to understand our origins, is universal. How did we get here? Are we alone? What does the future hold? These overarching questions lead to more focused, fundamental science questions about our solar system: How did the Sun's family of planets, satellites, and minor bodies originate and evolve? What are the characteristics of the solar system that lead to habitable environments? How and where could life begin and evolve in the solar system? What are the characteristics of small bodies and planetary environments and what potential hazards or resources do they hold? To address these science questions, NASA relies on various flight missions, research and analysis (R&A) and technology development. There are seven programs within the Planetary Science Theme: R&A, Lunar Quest, Discovery, New Frontiers, Mars Exploration, Outer Planets, and Technology. R&A supports two operating missions with international partners (Rosetta and Hayabusa), as well as sample curation, data archiving, dissemination and analysis, and Near Earth Object Observations. The Lunar Quest Program consists of small robotic spacecraft missions, Missions of Opportunity, Lunar Science Institute, and R&A. Discovery has two spacecraft in prime mission operations (MESSENGER and Dawn), an instrument operating on an ESA Mars Express mission (ASPERA-3), a mission in its development phase (GRAIL), three Missions of Opportunities (M3, Strofio, and LaRa), and three investigations using re-purposed spacecraft: EPOCh and DIXI hosted on the Deep Impact spacecraft and NExT hosted on the Stardust spacecraft. -

Planetary Science Update & Perspectives on Venus Exploration

Planetary Science Update & Perspectives on Venus Exploration Presentation at VEXAG James L. Green Director, Planetary Science Division May 6, 2008 1 Outline • FY09 Presidents Budget • Venus exploration opportunities: – Plans for next New Frontiers – Plans for next Discovery – Plans for SALMON – R&A opportunities 2 BUDGET BY SCIENCE THEME 3 Planetary Division 4 Planetary Division 5 What Changed, What’s the Same What Changed: • Initiated an Outer Planets Flagship (OPF) study activity joint with ESA/JAXA. • Lunar Science Research augmented to include a series of small lunar spacecraft. • Augments and enhances R&A to return more results from Planetary missions. • Discovery Program: Includes the recently selected MoOs (EPOXI and Stardust-NExT), adds Aspera-3 2nd extension (ESA/Mars Express), and selected GRAIL. • Preserves critical ISP work FY08 thru FY10, but deletes outyear activities in favor of more critical R&A and RPS enhancements. • Completes the Advanced Stirling RPS development and prepares for flight demonstration. • Mars Scout 2011 delayed to 2013 due to conflict of interest discovered during proposal evaluation. • Direction to the Mars Program to study Mars Sample Return (MSR) as a next decade goal • Expands US participation on the ESA/ExoMars mission by funding the potential selection of BOTH candidate U.S. instruments and EDL support. What’s the Same: • Discovery Program: MESSENGER, Dawn, Mars Express/Aspera-3, Chandraayn/MMM • New Frontiers Program: Juno and New Horizons • Mars Program: Odyssey, MER, MRO, Phoenix, MSL • Research -

OLLI Talk on Exoplanets

OLLI SC211 SPACE EXPLORATION: THE SEARCH FOR LIFE BEYOND EARTH April 13, 2017 Michal Peri NASA Solar System Ambassador Exoplanet2 Detection • Methods • Missions • Discoveries • Resources Image: C. Pulliam & D. Aguilar/CfA A long history … in our imaginations 3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giordano_Bruno#/media/File:Relief_Bruno_Campo_dei_Fiori_n1.jpg Giordano Bruno in his De l'infinito universo et mondi (1584) suggested that "stars are other suns with their own planets” that “have no less virtue nor a nature different to that of our earth" and, like Earth, "contain animals and inhabitants.” For this heresy, he was burned by the inquisition. 3 https://www.loc.gov/today/cyberlc/feature_wdesc.php?rec=7148 5 Detection Methods Radial Velocity 619 planets Gravitational Microlensing 44 planets Direct Imaging 44 planets Transit 2771 planets Velocity generates Doppler 7 Shift Sound star receding star approaching Light wave “stretched” → red shift wave “squashed” → blue shift Orbiting planet causes Doppler shift in starlight 8 https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/interactable/11/ Radial Velocity Method 9 • The most successful method of detecting exoplanets pre-2010 • Doppler shifts in the stellar spectrum reveal presence of planetary companion(s) • Measure lower limit of the planetary mass and orbital parameters Doppler Shift Time Nikole K. Lewis, STScI Radial Velocity Detections Radial Velocity 1992 Planetary Mass 10 Detection Methods Radial Velocity 619 planets Gravitational Microlensing 44 planets Direct Imaging 44 planets Transit 2771 planets • Microlens -

Simulation of Attitude and Orbital Disturbances Acting on ASPECT Satellite in the Vicinity of the Binary Asteroid Didymos

Simulation of attitude and orbital disturbances acting on ASPECT satellite in the vicinity of the binary asteroid Didymos Erick Flores García Space Engineering, masters level (120 credits) 2017 Luleå University of Technology Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering Simulation of attitude and orbital disturbances acting on ASPECT satellite in the vicinity of the binary asteroid Didymos Erick Flores Garcia School of Electrical Engineering Thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Master of Science in Technology. Espoo December 6, 2016 Thesis supervisors: Prof. Jaan Praks Dr. Leonard Felicetti Aalto University Luleå University of Technology School of Electrical Engineering Thesis advisors: M.Sc. Tuomas Tikka M.Sc. Nemanja Jovanović aalto university abstract of the school of electrical engineering master’s thesis Author: Erick Flores Garcia Title: Simulation of attitude and orbital disturbances acting on ASPECT satellite in the vicinity of the binary asteroid Didymos Date: December 6, 2016 Language: English Number of pages: 9+84 Department of Radio Science and Engineering Professorship: Automation Technology Supervisor: Prof. Jaan Praks Advisors: M.Sc. Tuomas Tikka, M.Sc. Nemanja JovanoviÊ Asteroid missions are gaining interest from the scientific community and many new missions are planned. The Didymos binary asteroid is a Near-Earth Object and the target of the Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment (AIDA). This joint mission, developed by NASA and ESA, brings the possibility to build one of the first CubeSats for deep space missions: the ASPECT satellite. Navigation systems of a deep space satellite differ greatly from the common planetary missions. Orbital environment close to an asteroid requires a case-by-case analysis. -

Thermal Infrared Imaging Experiments of C-Type Asteroid 162173 Ryugu on Hayabusa2

Space Sci Rev DOI 10.1007/s11214-016-0286-8 Thermal Infrared Imaging Experiments of C-Type Asteroid 162173 Ryugu on Hayabusa2 Tatsuaki Okada 1,2 · Tetsuya Fukuhara3 · Satoshi Tanaka1 · Makoto Taguchi3 · Takeshi Imamura4 · Takehiko Arai 1 · Hiroki Senshu5 · Yoshiko Ogawa6 · Hirohide Demura6 · Kohei Kitazato6 · Ryosuke Nakamura7 · Toru Kouyama7 · Tomohiko Sekiguchi8 · Sunao Hasegawa1 · Tsuneo Matsunaga9 · Takehiko Wada1 · Jun Takita2 · Naoya Sakatani1 · Yamato Horikawa10 · Ken Endo6 · Jörn Helbert11 · Thomas G. Müller12 · Axel Hagermann13 Received: 24 September 2015 / Accepted: 31 August 2016 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The thermal infrared imager TIR onboard Hayabusa2 has been developed to in- vestigate thermo-physical properties of C-type, near-Earth asteroid 162173 Ryugu. TIR is one of the remote science instruments on Hayabusa2 designed to understand the nature of a volatile-rich solar system small body, but it also has significant mission objectives to pro- vide information on surface physical properties and conditions for sampling site selection B T. Okada [email protected] 1 Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Sagamihara, Japan 2 Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo Tokyo, Japan 3 Rikkyo University, Tokyo, Japan 4 Graduate School of Frontiers Sciences, The University of Tokyo Kashiwa, Japan 5 Planetary Exploration Research Center, Chiba Institute of Technology, Narashino, Japan 6 Center -

THE ARECIBO OBSERVATORY PLANETARY RADAR SYSTEM. P. A. Taylor 1, M. C. Nolan2, E. G. Rivera-Valentın1, J. E. Richardson1, L. A

47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2016) 2534.pdf THE ARECIBO OBSERVATORY PLANETARY RADAR SYSTEM. P. A. Taylor1, M. C. Nolan2, E. G. Rivera-Valent´ın1, J. E. Richardson1, L. A. Rodriguez-Ford1, L. F. Zambrano-Marin1, E. S. Howell2, and J. T. Schmelz1; 1Arecibo Observatory, Universities Space Research Association, HC 3 Box 53995, Arecibo, PR 00612 ([email protected]); 2Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, 1629 E. University Blvd., Tucson, AZ 85721. Introduction: The William E. Gordon telescope at of Solar System objects at radio wavelengths. The Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico is the largest and unmatched sensitivity of Arecibo allows for detection most sensitive single-dish radio telescope and the most of any potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA; absolute active and powerful planetary radar facility in the world. magnitude H < 22) that comes within ∼0.05 AU of Since opening in 1963, Arecibo has made significant Earth (∼20 lunar distances) and most any asteroid scientific contributions in the fields of planetary science, larger than ∼10 meters (H < 27) within ∼0.015 AU radio astronomy, and space and atmospheric sciences. (∼6 lunar distances) in the Arecibo declination window Arecibo is a facility of the National Science Founda- (0◦ to +38◦), as well as objects as far away as Saturn. tion (NSF) operated under cooperative agreement with In terms of near-Earth objects, Arecibo observations SRI International along with Universities Space Re- are critical for identifying those objects that may be on search Association and Universidad Metropolitana, part a collision course with Earth in addition to providing of the Ana G. -

The Value of the Keck Observatory to NASA and Its Scientific Community

The Value of the Keck Observatory to NASA and Its Scientific Community Rachel Akeson1 and Tom Greene2, NASA representatives to the Keck Science Steering Committee Endorsed by: Geoffrey Bryden Geoff Marcy Bruce Carney Aki Roberge Heidi Hammel Travis Barman Mark Marley Antonin Bouchez Rosemary Killen Jason Wright Nick Siegler Chris Gelino Bruce Macintosh Rafael Millan-Gabet Ian McLean John Johnson Laurence Trafton Jim Lyke Joan Najita Dawn Gelino Peter Plavchan Josh Eisner Joshua Winn Chad Bender Kevin Covey Mark Swain William Herbst Franck Marchis Kathy Rages Andrew Howard Al Conrad Steve Vogt William Grundy Richard Barry 1 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, California Institute of Technology, Pasadean, CA [email protected], phone: 626-398-9227 2 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA The Value of the Keck Observatory to NASA and Its Scientific Community 1 Executive Summary Over the last 13 years, NASA and its astrophysics and planetary science communities have greatly benefited from access to the Keck Observatory, the world’s largest optical/infrared telescopes. Studies using NASA Keck time have ranged from observations of the closest solar system bodies to discoveries of many of the known extrasolar planets. Observations at Keck have supported spaceflight missions to Mercury and the technology development of the James Webb Space Telescope. Access to Keck for the NASA community is an extremely cost effective method for NASA to meet its strategic goals and we encourage NASA to continue its long-term partnership with the Keck Observatory. 2 The Keck Observatory The two 10-meter telescopes of the Keck Observatory are the world’s largest optical and infrared telescopes and are located on Mauna Kea, one of the world’s premier sites for astronomy. -

EPOXI at Comet Hartley 2

EPOXI at Comet Hartley 2 Michael F. A'HearnI', Michaelj. S. Belton', W. Alan Delamere3, Lori M. Feagal,Donald Hampton4, jochen Kissel5, Kenneth P. Klaasen", Lucy A. McFaddenJ,7, Karen j. Meech", H.jay Melosh9•lo, Peter H. Schultzll, jessica M. Sunshinel, Peter C. Thomas!2, Joseph Veverka", Dennis D. Wellnitzl, Donald K. Yeomans", Sebastien Bessel, Dennis Bodewitsl, Timothy j. Bowling!O, Brian T. Carcichl', Steven M. Collins", Tony L. Farnhaml, Olivier Groussin 13, Brendan Hermalynl1, Michael S. Kelley!, Michael S. Kelley14, jian-Yang LP, Don j. Lindlerls, Carey M. Lisse!6, Stephanie A. McLaughlin!, Fn3deric Merlin1.17, Silvia Protopapa!, james E. Richardson!O, jade L. Williams! !Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park MD 20742-2421 USA. 'Belton Space Exploration Initiatives LLC, 430 S. Randolph Way, Tucson AZ 85716 USA. 3Delamere Support Services, 525 Mapleton Ave., Boulder CO 80304 'University of Alaska - Fairbanks, 5Max-Planck-Institut: Sonnensystemforschung, 6jet Propulsion Laboratory, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena CA 91109, 'NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 8University of Hawaii, 9University of Arizona, !OPurdue University, "Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence RI 02912 USA, 12Cornell University, Ithaca NY, USA, 13Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille, Universite de Provence and CNRS, Marseille, France, 14Planetary Science Division, NASA Headquarters, Mail Suite 3V71, 300 E St. SW, Washington DC 20546, 15Sigma Space Corp" 4600 Forbes Blvd., Lanham MD 20706 USA. !6jHU-Applied Physics Laboratory, 11100 johns Hopkins Rd., Laurel MD 20723 USA, 17LESIA. Observatoire de Paris, Universite Paris 7, Batiment 17, 5 place jules janssen, Meudon Principal Cedex 92195 France *To whom correspondence should he addressed. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Nalin H. Samarasinha

CURRICULUM VITAE Nalin H. Samarasinha CONTACT INFORMATION: Planetary Science Institute (PSI) 1700 East Fort Lowell Road Suite 106 Tucson, AZ 85719 USA. Telephone: 520-622-6300 Fax: 520-795-3697 E-Mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D., Astronomy, 1992, University of Maryland M.S., Astronomy, 1985, University of Maryland B.Sc., Physics 1st Class Honours, 1981, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: 2005-present, Senior Scientist, Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona. 2004-2005, Research Scientist, Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona. 2006-2009, Associate Scientist, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona. 2001-2006, Assistant Scientist, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona. 1996-2000, Research Associate, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona. 1992-1996, Postdoctoral Researcher, National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona. 1987-1991, Research Assistant, Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland. 1982-1986, Teaching Assistant, Astronomy Program, University of Maryland. 1981-1982, Assistant Lecturer, Department of Physics, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka RESEARCH INTERESTS: Research interests are focused on understanding the physical, structural, dynamical, and chemical properties of small bodies in the solar system and their origin and evolution • Rotational studies of comets • Physics and chemistry of nuclei and comae of comets • Rotational and physical properties of asteroids and Trans-Neptunian-Objects • Structural properties of small