Homeless Persons) Act of 1977 Amy B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Summary

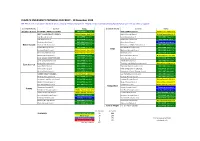

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 10 December 2019 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council Campaign in progress West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge -

![Review Into the Best Value Delivery of the Environmental Health out of Hours Service for Sevenoaks District Council [And Dartford Borough Council]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1027/review-into-the-best-value-delivery-of-the-environmental-health-out-of-hours-service-for-sevenoaks-district-council-and-dartford-borough-council-111027.webp)

Review Into the Best Value Delivery of the Environmental Health out of Hours Service for Sevenoaks District Council [And Dartford Borough Council]

REVIEW INTO THE BEST VALUE DELIVERY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH OUT OF HOURS SERVICE FOR SEVENOAKS DISTRICT COUNCIL [AND DARTFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL] Cabinet - 19 April 2018 Report of the: Chief Officer Environmental & Operational Services Status: For recommendation to Cabinet Also considered by: Direct and Trading Advisory Committee - 13 March 2018 Key Decision: Yes Executive Summary: The shared service Environmental Health team currently provides an Out of Hours (OOH) Service to deal with complaints from residents within the Sevenoaks and Dartford districts. This service currently operates everyday throughout the year between 17:00 and 22:00 Monday to Thursday, 17:00 to 00:00 Friday, 08:00 to 00:00 Saturday and 08:00 to 22:00 Sunday. Demand for the service is shown to vary significantly throughout the year and by day of the week. Many of the calls received are not urgent and do not require immediate action. These can be managed the next working day during office hours in accordance with agreed performance indicators. In the past 18 months, experienced officers have left the OOH Service, and there is now a serious issue with fully staffing the Service in its existing format. This report recommends that the OOH service targets Environmental Health Officer resource at times of peak demand whilst simultaneously empowering the CCTV team to respond, record and provide advice to the majority of ‘one off’ complaints received by the service. The existing OOH provision for serious or emergency public health complaints will be extended via a year round cascade call system. This report supports the Key Aim of Safe Communities and Green Environment Portfolio Holder Cllr. -

Tourism and Culture Strategy Development Update Report To

Subject: Tourism and Culture Strategy Development Update Report to: ELT – Monday 5th November 2018 Economic Development Committee – Monday 19th November 2018 Report by: Kate Watts – Strategic Director Paula Boyce – Head of IT Marketing and Communications This report provides committee Members with an update of progress on the development a new Tourism and Culture Strategy for the Borough and in doing so, it asks Members to resolve to a number of additional developmental steps being taken with an amended timeline for the completion of the work to April 2019. To undertake these additional developmental steps Members are asked to allocate £20,000 from the Council’s special projects reserve funding. 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 On Monday 16th July 2018 Members of Economic Development Committee resolved to create a new Tourism and Culture Strategy for Great Yarmouth. 1.2 Since the Council’s Economic Development Committee resolved to develop the new Tourism and Culture Strategy, a number of activities have taken place. This report updates Members with progress so far and outlines to Members the next steps in creating what has been recognised by our stakeholders as an important document for the Borough. 2. PROGRESS SO FAR 2.1 As part of the development work for this strategy, officers and Members from the Council’s Economic Development Committee undertook a study tour in October visiting cultural attractions in both Hastings and Margate. In doing so, the group met with officers, Members and private sector partners in both Thanet District Council and Hastings Borough Council area, learning about the role of each Council in terms of catalysts for investment to add value to and improve the local tourism and cultural offer in each area. -

Streets for All South East

Streets for All South East Consultation draft copy Summary In 2017 Historic England published an updated national edition of Streets for All, a practical guide for anyone involved in planning and implementing highways and other public realm works in sensitive historic locations. It shows how improvements can be made to public spaces without harming their valued character, including specific recommendations for works to surfaces, street furniture, new equipment, traffic management infrastructure and environmental improvements. This supplementary document summarises the key messages of Streets for All in the context of the South East. It begins by explaining how historic character adds value to the region’s contemporary public realm before summarising some of the priorities and opportunities for further improvements to the South East’s streetscape. This guidance has been prepared by Martin Small, Historic Places Advisor in the South East, and Rowan Whimster. First published by English Heritage 20Ǔǘ. This edition published by Historic England 2017. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2017 Streets for All: South East Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice/caring-for-heritage/streets-for-all/ Front cover: Guildford, Surrey Granite setts have been a defining feature of Guildford’s steeply sloping High Street for 150 years. After years of unsatisfactory patched repairs, Surrey County Council recently took the bold decision to relay the 115,000 original setts using modern grouting products that reduce the trip hazards and maintain a consistent contour across the road, thus making it much easier for pedestrians to walk on. © Eilís Byrne The public realm From Kent to Oxfordshire, the South East of on the safety of children and on accessibility for England contains a wealth of historic cities, towns everyone. -

THE COASTAL COMMUNITIES of SOUTH EAST ENGLAND Recommendations to the South East

THE COASTAL COMMUNITIES OF SOUTH EAST ENGLAND Recommendations to the South East LEP Prof Steve Fothergill Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research Sheffield Hallam University Final report December 2012 1 Summary This report considers the policy implications arising from a statistical review of the South East’s coastal communities, completed in April 2012. It also builds on discussions involving coastal local authorities, private sector representatives and other local partners. The statistical review identified the South East’s coastal communities, which have a combined population of one million or around a quarter of the LEP total, as on average an area of social and economic disadvantage, well adrift of LEP averages and sometimes behind national averages as well. The review also flagged up important differences between places along the coast and put forward a six-fold classification of areas that has won wide support. The present report makes ten recommendations: 1. The South East LEP needs to be ‘spatially aware’. The big internal differences within the LEP area, and in particular the distinctive needs of the coastal strip, need to inform the full range of LEP activities. 2. Strategic plans and priorities should give special attention to the coastal strip. This includes in the allocation of resources. 3. Transport links to parts of the coast need improvement. Accessibility remains an important constraint in a number of local areas. 4. The seaside tourist industry should be treated as one of the drivers of economic growth. Tourism along the coast continues to employ as many people as manufacturing, and there are opportunities for growth. -

Barco De Vapor & Ors V Thanet District Council

Barco de Vapor v Thanet DC Neutral Citation Number: [2014] EWHC 490 (Ch) Case No: I/A 5 OF 2013 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION Rolls Building 7 Rolls Buildings Fetter Lane London EC4A 1NL Date: 27/02/2014 Before : MR JUSTICE BIRSS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : (1) BARCO DE VAPOR B.V. (2) ONDERWATER AGNEAUX B.V (3) JOHANNES QUIRINIUS WOUTERIUS MARIA ONDERWATER (Trading as JOINT CARRIER) Claimants - and - THANET DISTRICT COUNCIL Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Andrew Henshaw QC and Emily MacKenzie (instructed by Thomas Cooper) for the Claimants Simon Kverndal QC and Philip Woolfe (instructed by the Defendant) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 11th, 12th, 16th and 17th December 2013 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. THE HON. MR JUSTICE BIRSS Barco de Vapor v Thanet DC Mr Justice Birss : Topic Paragraph Introduction 1 The Witnesses 11 The law 20 Breach of statutory duty 30 EU law 38 Francovich damages 61 Analysis of the events 71 Events in 2011 76 The monitoring group – early 2012 100 Later in 2012 106 Access to contingency plans 112 The 29th August incident 113 Events on 12th September 121 The ban on 13th September 149 After the ban 158 Applying the law to the facts 168 Was the ban a justifiable breach of Art 35 TFEU? 170 Damages under the Francovich principle? 174 Causation 191 Conclusion 192 Introduction 1. The long-distance transport of live animals for slaughter has been controversial for a long time. -

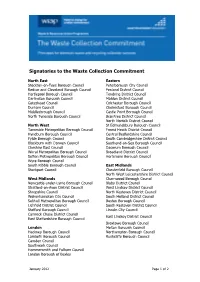

Waste Collection Commitment Signatories

Signatories to the Waste Collection Commitment North East Eastern Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council Peterborough City Council Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Fenland District Council Hartlepool Borough Council Tendring District Council Darlington Borough Council Maldon District Council Gateshead Council Colchester Borough Council Durham Council Chelmsford Borough Council Middlesbrough Council Castle Point Borough Council North Tyneside Borough Council Braintree District Council North Norfolk District Council North West St Edmundsbury Borough Council Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Forest Heath District Council Hyndburn Borough Council Central Bedfordshire Council Fylde Borough Council South Cambridgeshire District Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Southend-on-Sea Borough Council Cheshire East Council Dacorum Borough Council Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Broadland District Council Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council Hertsmere Borough Council Wyre Borough Council South Ribble Borough Council East Midlands Stockport Council Chesterfield Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council West Midlands Charnwood Borough Council Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Blaby District Council Stratford-on-Avon District Council West Lindsey District Council Shropshire Council North Kesteven District Council Wolverhampton City Council South Holland District Council Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Boston Borough Council Lichfield District Council South Kesteven District Council Stafford Borough Council Lincoln City -

Performance Standards for 2007/8 Consultation

Proposed Planning Best Value Performance Standards for 2007/8 Consultation A consultation paper Proposed Planning Best Value Performance Standards for 2007/8 Consultation October 2006 Department for Communities and Local Government On 5th May 2006 the responsibilities of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) transferred to the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4400 Website: www.communities.gov.uk © Crown Copyright, 2006 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Any other use of the contents of this publication would require a copyright licence. Please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/system/online/pLogin.asp, or by writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or email: [email protected] If you require this publication in an alternative format please email [email protected] DCLG Publications PO Box 236 Wetherby West Yorkshire LS23 7NB Tel: 08701 226 236 Fax: 08701 226 237 Textphone: 08701 207 405 Email: [email protected] or online via the DCLG website: www.communities.gov.uk October 2006 Product Code: 06 PD 04181 Introduction The Government proposes to set further planning Best Value performance standards in 2007/08 under section 4 of the Local Government Act 1999. -

Thanet District Council Action Plan

Thanet District Council – Climate Change Action Plan 1 & 2 Climate Change Action Plan 1- Actions underway and committed We are using this action plan as an initial framework for our response to the climate and ecological emergency. This action plan provides an outline of actions already in progress and this is a working document. Action Plan 2 contains all proposed actions not yet started or funded. Areas of focus are those which are already outlined as headings within the Kent Environment Strategy. https://www.kent.gov.uk/about-the-council/strategies-and-policies/environment-waste-and-planning-policies/environmental-policies/kent-environ ment-strategy Housing Financial implications: Already Progress- budgeted/ Other Started/Pl external Lead External Area of focus Action Outcome Timescales departments anned/Pro funding officer stakeholders involved posed achieved or identified/ funding required? TDC is committed to increasing All TDC new Newbuild energy efficiency standards as build units schemes well as reducing the district's meet the complete in carbon footprint. Currently TDC energy 2020/21 and Already is proposing to install 23.6 kWp efficiency letting committed as Housing Housing of solar panel systems across requirements Started commences part of Total Strategy Planning Contractors the TDC Affordable Homes set out in the thereafter. contract Manager Programme - Phase 3. This will Building Reduction in value result, in a reduction of approx Regulations energy uses 50,090 kg of carbon and a Approved will be known generation of 18,202 kWh of Documents : from then. 1/38 Thanet District Council – Climate Change Action Plan 1 & 2 (renewable energy) electricity L1A over a five year period. -

Local Authorities Involved in LAD2, Organised Into County Area Consortia for the Purpose of the Scheme

Local Authorities involved in LAD2, organised into county area consortia for the purpose of the scheme. Bedfordshire Bedford Borough Central Bedfordshire Luton Borough Milton Keynes Berkshire Bracknell Forest Reading Slough West Berkshire Windsor & Maidenhead Wokingham Buckinghamshire Buckinghamshire Council Cambridge Cambridge City East Cambridgeshire District Fenland District Council Huntingdonshire District Peterborough City Council South Cambridgeshire District East Sussex Eastbourne Borough Hastings Borough Lewes District Rother District Council Wealden District Council Essex Basildon Braintree Brentwood Borough Council Castle Point Chelmsford Colchester Epping Forest Harlow Maldon Rochford Southend on Sea Tendring Thurrock Uttlesford District Hampshire Basingstoke & Deane Borough Council East Hampshire District Council Hart District Council Rushmoor Borough Council Test Valley Borough Council Winchester City Council Hertfordshire Broxbourne Borough Dacorum Borough East Herts District Council Hertsmere Borough North Hertfordshire District St Albans City & District Stevenage Borough Three Rivers District Watford Borough Welwyn Hatfield Borough Kent Ashford Borough Council Canterbury City Council Dartford Borough Council Dover District Council Folkestone & Hythe District Council Gravesham Borough Council Maidstone Borough Council Medway Council Sevenoaks District Council Swale Borough Council Thanet District Council Tonbridge & Malling Borough Council Tunbridge Wells Borough Council London Barking & Dagenham Bexley Bromley Camden City -

Ramsgate Urban Panel

Historic England Urban Panel Ramsgate Visit 28-29 September 2016 Final Report Contents 1. Executive Summary 2. About the Urban Panel 3. Background to the Ramsgate Visit 4. Ramsgate’s Historic Environment 5. Background to Planning for Ramsgate 6. The Panel’s visit 7. Analysis 8. Recommendations 9. Epilogue Urban Panel Report: Ramsgate 28-29 September 2016 Page 1 1. Executive Summary The Urban Panel visited Ramsgate on 28-9 September 2016 at the request of the District Council and was supported in its examination of both Ramsgate and the recent successes of regeneration in Margate by the Council’s staff. Ramsgate’s heritage provides a tangible and valuable resource for regeneration of the town – a town which, in spite of areas of wealth and success, also has a concentration of wards that fall within the top 10% of indices of deprivation. The Panel was invited to consider a number of related issues centring on the Harbour and its uses but also the neighbouring port and the adjoining parts of the town centre. The Panel was able to meet representatives of several community organisations over dinner, providing an opportunity to discuss the issues and opportunities facing the town in an informal atmosphere. In addition to a bus tour of the east and west cliff areas, the Panel undertook walking tours of the Royal Harbour and Harbour Street and environs to assess the current performance of the town centre and recent planning issues. The compact town centre and harbour, the Panel felt, provide an initial focus for visitors to explore which can act as a springboard to the heritage assets of the east and west cliffs. -

Kent and Medway Risk Profile

Kent & Medway Risk Profile Update 2017 Kent Fire & Rescue Service Kent & Medway Risk Profile Update 2017 Kent & Medway Risk Profile Update 2017 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 County Overview ...................................................................................................... 5 Demographics and Population Risk Factors ......................................................... 7 Population ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Household Types ................................................................................................................................. 9 Deprivation ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Overall County Risk ............................................................................................... 12 Dwellings ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Special Service RTC ........................................................................................................................... 13 Future Risk Modelling ....................................................................................................................... 13 Geodemographic Segmentation ..........................................................................