Historical Anomalies in the Law of Libel and Slander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

SAG-AFTRA to Honor Finest Performances of 2014 at the 21 St

! SAG-AFTRA to Honor Finest Performances of 2014 st ® at the 21 Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards Simulcast Live on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 25, 2015, at 8 p.m. (ET) / 5 p.m. (PT) The 21st Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards®, one of the awards season’s premier events, will honor outstanding performances from 2014 in five film categories and eight television categories, including the distinctive ensemble awards. The coveted Actor® statuettes will be handed out at the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center during a live simulcast on TNT and TBS Sunday, Jan. 25, 2015, at 8 p.m. (ET) / 5 p.m. (PT). TNT will present a primetime encore of the ceremony immediately following the live telecast. The SAG Awards can also be viewed live on the TNT and TBS websites, and also the Watch TNT and Watch TBS apps for iOS or Android. (Viewers must sign in using their TV service provider user name and password). Of the top industry honors presented to performers, only the SAG Awards are conferred solely by actors’ peers in the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Recording Artists (SAG-AFTRA). The SAG Awards was the first televised awards show created by a union to acknowledge the work of actors and the first to establish ensemble and cast awards. The presentation of this year’s SAG Awards marks the 18th telecast of this prestigious industry event on TNT and the ninth simulcast on TBS. This year's ceremony will be telecast internationally, as well as to U.S. -

Krimi Down Under

Fernsehen 14 Tage TV-Programm 30.11. bis 13.11.2017 „Top Of The Lake: China Girl“ ab 7.12. bei Arte Krimi Down Under Im Spiegel der Nostalgie Stranger Things 2 Feature über den Regisseur Andrej Die großartige zweite Stafel der Tarkowski im Kulturradio Überraschungsserie bei Netlix Tip2517_001 1 23.11.17 17:13 FERNSEHEN 30.11. – 13.12. SEITENBLICKE Fett und arm VOM TELEVISOR Thomas Ebeling, Vorstandsvorsit- zender der Pro7Sat.1 Media SE, kennt seine Kunden: In einer Tele- fonkonferenz mit einer Gruppe von Analysten und Börsenfachleuten charakterisiert er seine Zuschauer NETFLIX ganz unverblümt: „Sie sind Men- FOTO schen, ein bisschen fettleibig und ein bisschen arm, die immer noch gerne auf dem Sofa sitzen, sich zurücklehnen und gerne unterhal- ten werden wollen.“ Das ist jetzt nicht so überraschend, ARTE / SEE-SAW FILMS/SCREEN GRAB denn das die Privat-TV-Bosse ihre FOTO Zuschauer für doof halten, kann Die Rolle ihres Lebens: Elisabeth Moss ist die australische Ermittlerin Robin Griffith man täglich an der Programmzu- sammenstellung sehen: Billigst produzierter Eigenschrott, Scrip- KRIMI DOWN UNDER ted-reality-Dokusoaps, Schleich- werbung-Shows, Chart-Sendun- gen, bestenfalls noch immer die gleichen TV-Komödien und -Krimis Frauen unter Wasser in Endlosschleife (jemand hat mal Die zweite Staffel von Jane Campions „Top of the Lake“ kreist um ausgerechnet, dass „Navy CIS“ in ein Bordell in Sydney – und ein verschwundenes Mädchen all seinen Inkarnationen 450-mal im Monat läuft), kein Mut für Neues und kein Durchhaltevermögen, in Koffer sinkt auf den Meeresbo- Staffel sollte es anfangs bleiben. Doch wenn mal etwas nicht sofort funk- E den. -

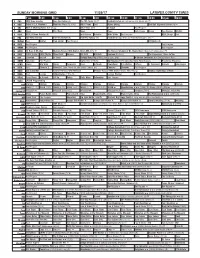

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

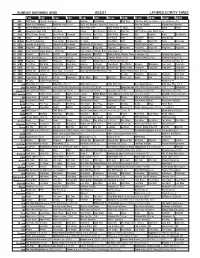

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

SAG-AFTRA to Honor Finest Performances of 2013 at the 20 Th

SAG-AFTRA to Honor Finest Performances of 2013 th ® at the 20 Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards Simulcast Live on TNT and TBS on Saturday, Jan. 18, 2014, at 8 p.m. (ET) / 5 p.m. (PT) The 20th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards®, one of the awards season’s premier events, will honor outstanding performances from 2013 in five film categories and eight television categories, including the distinctive ensemble awards. The coveted Actor® statuettes will be handed out at the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center during a live simulcast on TNT and TBS Saturday, Jan. 18, 2014, at 8 p.m. (ET) / 5 p.m. (PT). TNT will present a primetime encore of the ceremony at 10 p.m. (ET) / 7 p.m. (PT), immediately following the live telecast. A live stream of the SAG Awards can also be viewed online through the TNT and TBS websites, as well as through the Watch TBS and Watch TNT apps for iOS or Android. (Viewers must sign in using their TV provider user name and password in order to view the livestream.) Of the top industry honors presented to performers, only the SAG Awards are conferred solely by actors’ peers in the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Recording Artists (SAG-AFTRA). The SAG Awards was the first televised awards show created by a union to acknowledge the work of actors and the first to establish ensemble and cast awards. The presentation of this year’s SAG Awards marks the 17th telecast of this prestigious industry event on TNT and the eighth simulcast on TBS. -

October 30, 2013 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2013 • VOL. 24, NO.13 $1.25 Have a Spooktacular Hallowe'en everyone! KLONDIKEThe Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Singers SUN Still not much ice, but the Ferry is done The Jerry Cans Relatively small amounts of ice appeared in front of Dawson last week, but not enough to bother the George Black, and after two days of increasing pans, there seemed to be less on Friday than on Wednesday and Thursday. By Saturday the Highways Dept. had made its decision, shown here, which was amended to read "NOON" by Monday morning. It's later than last year though, and it sure beats the six-hour panic of 2012. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue Maximilian's has all kinds of Hospital update 3 What is REM? 10 & 19 A report from Columbia 13 Hospital siding goes on, again. The Rural Experiential Model Anna Vogt reports from Bogota. candles to keep you home Comes to RSS. cozy and bright this winter. What to see and do in Dawson! 2 More info on the Hospital 5 SOVA students hybredize 11 Authors on Eighth entries 20 & 21 Council Tribute to Dick North 3 Legion news 6 TV Guide 14-18 Business Directory & Job Board 23 Uffish Thoughts 4 Tourism roundup report 7 Murphy on Berton House 19 City Notices 24 Happy 26th Birthday Andrea Parent! P2 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2013 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: SOVA ADMIN OFFICE HOUrs This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. -

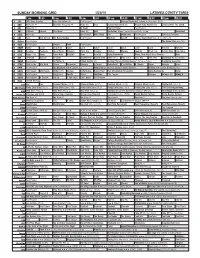

Sunday Morning Grid 11/26/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/26/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Buffalo Bills at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Alpine Skiing Red Bull Signature Series (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Chicago Bears at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 89 Blocks (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR I’ll Have It My Way Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. Å 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Santana IV (TV14) The Carpenters: Close to You 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Holiday Road Trip (2013) Ashley Scott. (PG) A Golden Christmas ›› (2009) Andrea Roth. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Sor Tequila (1977, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

WEEKSWORTH, DAILY COURIER, Grants Pass, Oregon • FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2021 THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS Saturday Wednesday the Goldbergs 90 Day: the Single Life ABC 8 P.M

Daily Courier We e k’sWor th THE TV MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 25-OCTOBER 1, 2021 Nathan Fillion returns as THE ROOKIE for a fourth season on CBS ‘The Rookie’ returns after cliffhanger drama By Kyla Brewer TV Media Cop shows have been around practically since the dawn of television, and there’s still nothing quite like a good police drama, especially one with a nail-biting cliffhanger season finale. After months of waiting, anxious fans will finally find out what happens when a prime-time hit returns to the airwaves. Nathan Fillion reprises his role as John Nolan, a cop who sets out to find a col- league after she goes missing in the sea- son premiere of “The Rookie,” airing Sun- day on ABC. The debut marks the fourth season of the hour-long drama centered on Nolan, a 40-something cop — and oldest rookie in the history of the LAPD — who works at the Mid-Wilshire Division of the Los Ange- les Police Department. The police drama is the latest in a string of hits for Canadian-American actor Fillion, who rose to fame as Capt. Mal- colm Reynolds in the cult favorite TV series “Firefly” and its subsequent spinoff film, “Serenity” (2005), and as sleuthing mystery writer Richard Castle in the ABC crime drama “Castle.” Born and raised in Edmonton, Fillion moved south to pursue a career in acting, landing roles in TV shows “One Life to Live” and “Two Guys, a Girl and a Pizza Place” and in the movie “Saving Private Ryan” (1998). Now, he’s leading the cast of one of prime time’s highest-rated network series: “The Rookie.” At the end of last season, pregnant Det. -

Calendar of Events As We Begin Our 41St Year, It Is an Honor and a Privilege to Serve As Your President

Th 2015 FALL NEWSLETTER Greetings from the PRESIDENT Calendar of Events As we begin our 41st year, it is an honor and a privilege to serve as your President. I have always believed GUILD INSTITUTE IN CHRISTIAN FAMILY STUDIES that volunteering should be fun and Convocation . 11:00 a .m . exciting, and The Guild has a variety Luncheon . .. 12:15 p .m . of committees from which to choose. Wednesday, October 14, 2015 I encourage you to sign up on a Speaker: Dr . Hunter Baker committee and bring a friend to one Morris Cultural Arts Center of our planned events. We installed our new Board on FALL COFFEE HONORING NEW MEMBERS . 10:00 a .m . May 15, 2015. A special thank you to Cheryl Kaminski who Thursday, October 22, 2015 did an outstanding job leading our program. My chosen Home of Sharon & William Morris scripture was Matthew 10:30-31, And even the very hairs of your head are numbered, so don’t be afraid, you are worth GUILD ANNUAL CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON . 11:00 a .m . more than many sparrows. Singing acappella, Mon’Sher Wednesday, December 9, 2015 entertained us with a beautiful rendition of the hymn, “His Speaker: Kelly Siegler Eye is on the Sparrow.” A big thank you goes to Nancy River Oaks Country Club Shomette & Kathy Thompson and all the committee members who made this a truly beautiful Installation. COMMUNITY CHRISTMAS PARTY . 5:30 p .m . – 7:30 p .m . We have worked through the summer with our new Thursday, December 10, 2015 Board to provide several fun-filled events. -

“The List” -- Prime-Time Television Shows Niceole Has Watched. (Rules

“The List” -- Prime-time television shows Niceole has watched. (Rules: watched at least one full episode of a drama, comedy, or reality show, including reruns that aired in syndication.) 1. 1st & 10 2. The 100 3. 12 Monkeys 4. 2 Broke Girls 5. 20/20 6. 21 Jump Street 7. 227 8. 24 9. 240-Robert 10. 30 Rock 11. 3rd Rock from the Sun 12. The 4400 13. 48 Hours/48 Hours Mystery 14. 666 Park Avenue 15. 60 Minutes 16. 7th Heaven 17. 8 Simple Rules 18. 9 to 5 19. 90210 (new) 20. A to Z 21. A Gifted Man 22. A Year in the Life 23. A-Team 24. About a Boy 25. Absolutely Fabulous 26. According to Jim 27. Adam-12 28. The Addams Family 29. Adventures of Brisco County Jr. 30. Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet 31. The Affair 32. The After 33. Agent Carter 34. Agent X 35. Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. 36. Airwolf 37. Alcatraz 38. Alf 39. Alfred Hitchcock Presents 40. Alice 41. All American Girl 42. All in the Family 43. Allegiance 44. Ally McBeal 45. Almost Human 46. Almost Perfect 47. The Amazing Race 48. Amazing Stories 49. Amen 50. American Crime 51. American Crime Story: People vs. OJ Simpson 52. American Dad 53. American Horror Story 54. American Inventor 55. American Odyssey 56. The Americans 57. America's Funniest Home Videos 58. America’s Got Talent 59. America's Most Wanted 60. America's Next Top Model 61. The Andy Griffith Show 62. Angie 63. -

7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/15/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News All In Bull Riding FaldoForm One Shot Course PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Countdown NASCAR Cup Series Verizon 200 at the Brickyard. (N) 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Emeril 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of LaLiga Pre Spanish Primera Division Soccer 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Ankerberg Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News AAA Home Lock Accident? Floor Mop Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs Paid Prog. NeuroQ Cancer? News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Consult Beaute & Health Waterford Crystal Å Waterford Crystal Å Waterford Crystal Å Pamela McCoy Gems of Galerie de Bijoux Jewel 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Suze Orman’s Sinatra in Concert at Royal Festival Great Performances (TVG) Å Bee Gees: One Night Only (TVG) 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel Suze Orman’s 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa ››› (2008) (N) (PG) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R.