A Sense of Self Worth Action Research in the Jamaica All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter Post Compendium Jamaica

Letter Post Compendium Jamaica Currency : Dollar Jamaïquain Basic services Mail classification system (Conv., art. 17.4; Regs., art. 17-101) 1 Based on speed of treatment of items (Regs., art. 17-101.2: Yes 1.1 Priority and non-priority items may weigh up to 5 kilogrammes. Whether admitted or not: Yes 2 Based on contents of items: Yes 2.1 Letters and small packets weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.1). Whether admitted or not Yes (dispatch and receipt): 2.2 Printed papers weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.2). Whether admitted or not for Yes dispatch (obligatory for receipt): 3 Classification of post items to the letters according to their size (Conv., art. 17,art. 17-102.2) - Optional supplementary services 4 Insured items (Conv., art. 18.2.1; Regs., 18-001.1) 4.1 Whether admitted or not (dispatch and receipt): No 4.2 Whether admitted or not (receipt only): No 4.3 Declaration of value. Maximum sum 4.3.1 surface routes: SDR 4.3.2 air routes: SDR 4.3.3 Labels. CN 06 label or two labels (CN 04 and pink "Valeur déclarée" (insured) label) used: - 4.4 Offices participating in the service: - 4.5 Services used: 4.5.1 air services (IATA airline code): 4.5.2 sea services (names of shipping companies): 4.6 Office of exchange to which a duplicate CN 24 formal report must be sent (Regs., art.17-138.11): Office Name : Office Code : Address : Phone : Fax : E-mail 1 : E-mail 2: 5 Cash-on-delivery (COD) items (Conv., art. -

IV. SECTORAL TRADE POLICIES (1) 1. Jamaica Continues to Use Trade

WT/TPR/S/42 Trade Policies Review Page 84 IV. SECTORAL TRADE POLICIES (1) OVERVIEW 1. Jamaica continues to use trade policies and incentive schemes geared at promoting specific sectors. The National Industrial Policy identifies these sectors, focusing on activities where a comparative advantage is perceived to exist, such as tourism and on identifying others where it could be developed through policy actions, such as data processing and systems development. 2. Traditionally, Jamaica's endowments led to the development of activities linked to certain agricultural crops and minerals. Although agriculture and mining remain important, both sectors have lost GDP share to services and manufacturing. A number of incentives promote activity in manufacturing, including income tax exemptions, and import duty concessions for production for export outside of CARICOM. The main exporter in manufacturing is the textiles and clothing subsector, although the industry has been suffering from a loss of competitiveness and inability to fill bilateral export quotas in the past few years. A substantial part of the garment industry is located in free zones. 3. Jamaica's tariff structure offers higher levels of protection to goods with high value added and to agricultural products (Chart IV.1). Goods used as inputs are generally granted duty-free access. 4. The services sector is the largest and fastest growing in the Jamaican economy. Among services, tourism is the main earner of foreign exchange, generating around US$1.13 billion in 1997. After a period of privatization and reform, activities in the services sector have been largely liberalized, few restrictions remain and national treatment is prevalent. -

Jamaica's Parishes and Civil Registration Districts

Jamaican registration districts Jamaica’s parishes and civil registration districts [updated 2010 Aug 15] (adapted from a Wikimedia Commons image) Parishes were established as administrative districts at the English conquest of 1655. Though the boundaries have changed over the succeeding centuries, parishes remain Jamaica’s fundamental civil administrative unit. The three counties of Cornwall (green, on the map above), Middlesex (pink), and Surrey (yellow) have no administrative relevance. The present parishes were consolidated in 1866 with the re-division of eight now- extinct entities, none of which will have civil records. A good historical look at the parishes as they changed over time may be found on the privately compiled “Jamaican Parish Reference,” http://prestwidge.com/river/jamaicanparishes.html (cited 2010 Jul 1). Civil registration of vital records was mandated in 1878. For civil recording, parishes were subdivided into named registration districts. Districts record births, marriages (but not divorces), and deaths since the mandate. Actual recording might not have begun in a district until several years later after 1878. An important comment on Jamaican civil records may be found in the administrative history available on the Registrar General’s Department Website at http://apps.rgd.gov.jm/history/ (cited 2010 Jul 1). This list is split into halves: 1) a list of parishes with their districts organized alphabetically by code; and 2) an alphabetical index of district names as of the date below the title. As the Jamaican population grows and districts are added, the list of registration districts lengthens. The parish code lists are current to about 1995. Registration districts created after that date are followed by the parish name rather than their district code. -

JSIF Annual Report 2005-2006.Pdf

Our Mission The Jamaica Social Investment Fund (JSIF) will mobilise resources and channel these to community-based socio-economic infrastructure and social services projects. Through a national partnership between central and local government, communities and private and public organisations, the JSIF will address the immediate demands of communities in a manner that is quick, efficient, effective, transparent and non-partisan. In fulfilling its mandate, the JSIF will facilitate the empowerment of communities and assist in building national capacity to effectively implement community-based programmes aimed at social development. Ammended Notice Of Annual General Meeting NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT the Tenth Annual General Meeting of JAMAICA SOCIAL INVESTMENT FUND will be held at the Jamaica Pegasus Hotel, 81 Knutsford Bolevard, Kingston 5 on Wednesday October 4, 2006 at 2:00 p.m. for the fol- lowing purposes: Resolution 1: 1. To receive the Accounts for the period ended 31st March, 2006 and the reports of the Directors and Auditors thereon. Resolution 2: 2. To fix the remuneration of the Auditors or to determine the manner in which such remuneration is to be fixed. To consider and (if thought fit) pass the following Resolution: “That the Directors be and they are hereby authorized to fix the remuneration of the Auditors at a figure to be agreed with them” 3. To consider any other business that may be conducted at an Annual General Meeting. By Order of the Board Dated this 7th day of September, 2006 Howard N. Malcolm Secretary Board Of Directors Wesley Hughes, CD PhD (Econ) Scarlett Gillings, CD Chairman, JSIF Managing Director Director General Jamaica Social Investment Fund Planning Institute of Jamaica 1C-1F Pawsey Place 10-16 Grenada Way, Kingston 5 Kingston 5 Eleanor Jones, MA Marcia Edwards, MA Managing Director Land Acquisition & Resettlement Officer Environmental Solutions Ltd. -

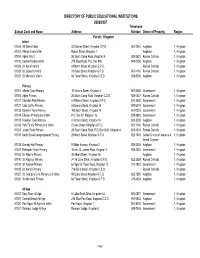

Ministry of Education Port Antonio Region Portland Black Hill All Age Old Post Post No

CONTENTS PAGE All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 - 7 Portland Black Hill All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Drapers All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Hope Bay All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Manchioneal All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 3 Rock Hall All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 St. Margaret’s Bay All Age .. .. .. .. .. 4 Windsor Castle All Age .. .. .. .. .. 4 - 5 St. Mary Paisley All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 St. Thomas Aeolus Valley All Age .. .. .. .. .. 5 - 6 Bull Bay All Age .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 7 Infant .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 - 9 Portland Boundbrook Infant .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Port Antonio Infant .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 - 8 St. Mary Carron Hall Infant .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Port Maria Infant .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 - 9 i CONTENTS PAGE Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 - 25 Portland Avocat Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 9 - 10 Cascade Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 10 Comfort Castle Primary & Junior High .. .. .. 11 Fellowship Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 11 - 12 Moore Town Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 13 Mount Hermon Primary & Junior High .. .. .. 13 - 14 St. Mary Castleton Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 14 - 15 Clonmel Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 15 - 16 Enfield Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 16 - 17 Highgate Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 17 - 19 Jackson Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 19 Mount Angus Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 20 Retreat Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. 20 - 22 St. Thomas Bath Primary & Junior High .. .. .. .. .. 22 - 23 Cedar Valley Primary & Junior High & Infant .. .. 23 - 24 Port Morant Primary -

Jamaica Church Missionary Society Chairman Presentation Synod 2014

DIOCESE OF JAMAICA & THE CAYMN ISLANDS JAMAICA CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY (JCMS) Chairman's Remarks The JCMS was established in 1861 with the specific mandate: To plan evangelistic and teaching missions; To carry out an on-going programme of evangelistic and social outreach; To undertake the dissemination of literature designed to educate and stimulate for greater involvement in mission on the part of the clergy and laity; To provide for training of lay leadership for the Missions; To accept responsibility for the establishment of Mission Stations in new areas and to raise funds for missionary work in Jamaica and overseas. REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2013 Status of our Mission Congregations and Changes During the Year The year began with one hundred and four (104) Missions and twenty seven (27) Chapels-of-Ease, and ended with one hundred and seven (107) Missions and twenty-eight (28) Chapels-of-Ease. Reason being that Synod of 2013 passed resolutions which changed the status of three settled congregations to missions EDUCATION AND EVANGELISM Evangelistic/Mission Work The commitment of the Jamaica Church Missionary Society to support congregations in organization and implementation of Evangelistic and Mission Work is on-going. It is committed to make grants for evangelistic pursuits to church leaders who request such assistance. EDUCATION AND EVANGELISM Missionary Activities - 2013 Sister Phyllis Thomas, Director of Evangelism / Head of the Church Army in Jamaica and her able team of Church Army Officers, were engaged in missionary activities as follows : EDUCATION AND EVANGELISM Missionary Activities - 2013 cont’d January 3-4: Combined Youth Alpha Retreat (Bishop Gibson and Glenmuir High Schools) at Mt. -

6 Directory.XLS

DIRECTORY OF PUBLIC EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS 2006/2007 Telephone School Code and Name Address Number Owner of Property Region Parish: Kingston Infant 01004 All Saints Infant 52 Charles Street, Kingston G.P.O. 967-2261 Anglican 1. Kingston 01002 Allman Town Infant Robert Street, Kingston 4 Anglican 1. Kingston 01006 Alpha Infant 26 South Camp Road, Kingston 4 928-2621 Roman Catholic 1. Kingston 01010 Central Branch Infant 27b Slipe Road, P.O. Box 996 948-0254 Anglican 1. Kingston 01026 St. Anne's Infant 48 North Street, Kingston G.P.O. Roman Catholic 1. Kingston 01029 St. Joseph's Infant 76 Duke Street, Kingston G.P.O. 967-4140 Roman Catholic 1. Kingston 01031 St. Michael's Infant 6a Tower Street, Kingston C.S.O. 928-8246 Anglican 1. Kingston Primary 01001 Allman Town Primary 19 Victoria Street, Kingston 4 967-3385 Government 1. Kingston 01005 Alpha Primary 26 South Camp Road, Kingston C.S.O. 928-4407 Roman Catholic 1. Kingston 01011 Chetolah Park Primary 6 Williams Street, Kingston G.P.O. 922-3628 Government 1. Kingston 01121 Clan Carthy Primary 5 Deanery Road, Kingston 16 928-5374 Government 1. Kingston 01135 Denham Town Primary 105 North Street, Kingston 14 967-0225 Government 1. Kingston 01014 Elletson Primary and Infant P.O. Box 87, Kingston 16 928-3880 Government 1. Kingston 01015 Franklyn Town Primary 4 Victoria Street, Kingston 16 928-2538 Anglican 1. Kingston 01016 Holy Family Primary and Infant 2 Laws Street, Kingston G.P.O. 922-7142 Roman Catholic 1. Kingston 01024 Jessie Ripoll Primary 26 South Camp Road, P.O. -

Iiatuatra Tiiitur � Vol

;iiatuatra tiiitur VoL. 13 _ KINGSTON, JAMAICA, AUGUST, 1938. No. 7 THE CHRISTIAN'S' HOPE The coming of the Lord has been in all REPORTS OF FURTHER PROCESS BY MRS. E. G. WHITE ages the hope of His true followers. Writing under date of July -11-PaStior The Saviour's parting promise upon Stockhausen reporiS, co4Ceiengi the ta- When the Saviour was aboht to be Olivet, that He would come again, lighted bernacle meetings at FalniOilth: "We are separated from His disciples, He comfort- up the future for His disciples, filling planning- to bind off (kite 'effoq,:he're== atis ed them in their sorrow with the assur- their hearts with joy and hope that week Wednesday night;anclil ance that He would come again: "Let not sorrows could not quench nor trials dim. for Montego Bay after ,that- -meeting. I your heart be troubled In My Amid suffering and persecution, "the think that Brother Robertson and Miss Father's house are many mansions appearing of the great God and our Sangster can look after ,things here from I go to prepare a place for you,. And if Saviour Jesus Christ" was the "blessed now on. We had an- attendance of forty I go and prepare a place for you, will hope." When the Thessalonian Christians last Sabbath with nineteen, ' enrolled .'in come .again; and receive you unto My- 'the baptismal claSs." - self." "The Son of man shall come in His glory,, arid all the holy Angels with Pastor H. Fletcher reports the organi- Him. Then shall He sit upon the throne zation of two more Sabbath schools in St. -

Jamaica: Assessment of the Damage Caused by Flood Rains and Landslides in Association with Hurricane Michelle, October 2001

GENERAL LC/C AR/G. 672 7 December 2001 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH JAMAICA: ASSESSMENT OF THE DAMAGE CAUSED BY FLOOD RAINS AND LANDSLIDES IN ASSOCIATION WITH HURRICANE MICHELLE, OCTOBER 2001 .... Implications for economic, social and environmental development ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean CARIBBEAN DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATION COMMITTEE Table of contents PREFACE This study was prepared for the Government of Jamaica following the significant physical damage and economic losses that the country sustained as a result of flood rains associated with the development of Hurricane Michelle. The Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) submitted a request for assistance in undertaking a social, environmental and economic impact assessment to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) on 14 November 2001. ECLAC responded with haste and modified its work plan to accommodate the request. A request for training in the use of the ECLAC Methodology to be delivered to personnel in Jamaica was deferred until the first quarter of 2002, as it was impossible to mount such an initiative at such short notice. This appraisal considers the consequences of the three instances of heavy rainfall that brought on the severe flooding and loss of property and livelihoods. The study was prepared by three members of the ECLAC Natural Disaster Damage Assessment Team over a period of one week in order to comply with the request that it be presented to the Prime Minister on 3 December 2001. The team has endeavoured to complete a workload that would take two weeks with a team of 15 members working assiduously with data already prepared in preliminary form by the national emergency stakeholders. -

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Acknowledgements This technical report is a joint product of the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) and the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), with support from the World Bank. The core task team at PIOJ consisted of Caren Nelson (Director, Policy Research Unit), Christopher O’Connor (Policy Analyst), Hugh Morris (Director, Modelling & Research Unit), Jumaine Taylor (Senior Economist), Frederick Gordon (Director, JamStats), Patrine Cole (GIS Analysit), and Suzette Johnson (Senior Policy Analyst), while Roxine Ricketts provided administrative support. The core task team at STATIN consisted of Leesha Delatie-Budair (Deputy Director General), Jessica Campbell (Senior Statistician), Kadi-Ann Hinds (Senior Statistician), Martin Brown (Senior Statistician), Amanda Lee (Statistician), O’Dayne Plummer (Statistician), Sue Yuen Lue Lim (Statistician), and Mirko Morant (Geographer). The core task team at the World Bank consisted of Juan Carlos Parra (Senior Economist) and Eduardo Ortiz (Consultant). Nubuo Yoshida (Lead Economist) and Maria Eugenia Genoni (Senior Economist) provided guidance and comments to previous versions of this report. The team benefited from the support and guidance provided by Carol Coy (Director General, STATIN) and Galina Sotirova (Country Manager, World Bank). We also want to thank the Geographical Services Unit in STATIN for drawing the final maps. 2 Methodology and data sources This document -

1 Rs,I Iusi :J, <

."',,';.:": +, ,' 1:--:•;: :: �1��rs,i�iusi�:J, <.. ,:_:.�· ?<,:·: ,:·J:, ·:\ .,-;:· '.miE�E'lii.C[Bts,1:�rj:�tt CONTENTS Page Citation, Interpretation and General Regulations 350B257-350B268 First Schedule-Boundary Description 350B269-350B272 Second Schedule-Use Classes Order 350B272-350B275 Class I-Shops 350B272-350B273 Class 2- Financial and Professional Services 350B273 Class 3-Restaurants And Cafes 350B273 Class 4-Drinking Establishments 350B273 Class 5-Hot Food Takeaways 350B273 Class 6-Business 350B273 Class 7-General Industry 350B274 Class 8-Storage Or Distribution 350B274 Class 9-Hotels 350B274 Class IO - Residential Institutions 350B274 Class I I -Secure Residential Institution 350B274 Class I2-Dwelling House 350B274 Class 13-Non-residential Institutions 350B274-350B275 Class I4�Assembly And Leisure 350B275 Third Schedule-Permitted Development 350B276 Pllrt I-Development within the curtilage of a Dwelling House 350B276-350B281 Part 2-Minor Operations 350B282-3 50B283 Part 3-Development By Local Authorities 350B283 Part 4-Temporary Buildings and Uses 350B284-350B285 Part 5-Agricultural Buildings and Operations 350B285-350B297 Part 6-Forestry Buildings and Operations 350B297-350B361 Part 7-Repairs to Unadopted Streets and Private Ways 350B361 Part 8-Repairs to Services 350B361 Part 9-Aviation Development 350B361-350B366 Part I0-Telecommunications Operations 350B367 Fomih Schedule-Notification Forms 350B368-350B369 Form A 350B368 Form B 350B368-350B369 FormC 350B369 31 Fifth Schedule-Statements 350B 0 3 Section 1-The Planning Framework -

The Small Farmer Inwestern Portland and Eastern St. Mary (Jamaica)

THE SMALL FARMER IN WESTERN PORTLAND AND EASTERN ST. MARY (JAMAICA) BASES FOR AN INTEGRATED RRAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Report of the Agriculture Sector Assessment team of the Offic_,- of International Cooperation and Development U.S. Department of Agriculture to USAID / JAMAICA and to the Ministry of Agriculture, Jamaica, Kingston, November 1978 The Small Farmer in Western Portland and Eastern St. Mary (Jamaica) Volume II TABLE OF CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION ........ ..................... i 1. THE TARGET AREA ..... ... ................... 1 1.1 Characteristics; Reasons for Selection ... ....... 1 1.2 Location of the Small Farmer ..... ............ 5 2. AGRICULTURE IN THE TARGET AREA .............. 2.1 2.Sal~am.......................... Small Farms 'C . .Prod.uc . .ion . .. .... 14141 2.2 Domestic Food Crop Production..... ... .. 14 2.3 Export Crops ..... .................... ... 15 - Bananas ..... ................... .... 21 - Coconuts ..... .................... ... 26 - Spices .... ....................... 29 3. PHY3ICAL ENVIRONMENT ..... ................ .. 31 3.1 Topographic Structure ... ............... .... 31 3.2 Climate ..... .... .................. .. 37 3.3 Rainfall Controls ..... .. ................. 38 3.4 Portland Soils ...... ................... 46 3.4.1 Characteristics ..... .. ................. 46 3.4.2 Erosion ..... ... ..................... 50 3.4.3 Soil Drainage ....... Typ . 53 3.4.4 Crop Recommendation by Soil Type ..... 56 3.5 Erosion Control Measures ... ................. 60 4. SMALL FARM RESOURCES AND PRODUCTION IN