Antonio Vivaldi. Biography. Catalogue of Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus Hwv 232 Dixit Dominus Rv 807 in Furore Iustissimae Irae Rv 626

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus hwv 232 Dixit Dominus rv 807 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626 La Nuova Musica Lucy Crowe soprano dir. DAVID BATES 1 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Dixit Dominus rv 807 1 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 1’51 2 Donec ponam inimicos tuos (chorus) 3’34 3 Virgam virtutis tuae (soprano I) 3’06 4 Tecum principium in die virtutis (tenor I & II) 2’08 5 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’12 6 Dominus a dextris tuis (tenor I) 1’54 7 Judicabit in nationibus (chorus) 2’48 8 De torrente in via bibet (countertenor) 3’20 9 Gloria Patri, et Filio (soprano I & II) 2’27 10 Sicut erat in principio (chorus) 0’33 11 Amen (chorus) 2’47 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626* 12 In furore iustissimae (aria) 4’55 13 Miserationem Pater piissime (recitative) 0’39 14 Tunc meus fletus evadet laetus (aria) 6’58 15 Alleluia 1’28 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759) Dixit Dominus hwv 232 16 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 5’49 17 Virgam virtutis tuae (countertenor) 2’49 18 Tecum principium in die virtutis (soprano I) 3’31 19 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’37 20 Tu es sacerdos in aeternum (chorus) 1’19 21 Dominus a dextris tuis (SSTTB & chorus) 7’32 22 De torrente in via bibet (soprano I, II & chorus) 3’55 23 Gloria Patri, et Filio (chorus) 6’33 La Nuova Musica *with Lucy Crowe soprano 12-15 DAVID BATES director Anna Dennis, Helen-Jane Howells, Augusta Hebbert, Esther Brazil, sopranos Christopher Lowrey, countertenor Simon Wall, Tom Raskin, tenors James Arthur, bass 2 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi Dixit Dominus ithin the Roman Catholic liturgy Psalm 109 aria in Vivaldi’s opera La fida ninfa (1732). -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Celestial Vivaldi

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Celestial Vivaldi PAUL DYER artistic director and conductor SIOBHAN STAGG soprano BELINDA MONTGOMERY soprano JENNIFER COOK soprano TIMOTHY CHUNG sountertenor TIM REYNOLds tenor JAMES ROSER bass BRANDENBURG CHOIR THE CHOIR OF TRINITY COLLEGE (University Of Melbourne) MELBOURNE GRAmmAR SCHOOL CHAPEL CHOIR P ROGRA M Rebel Les Elémens Corrette Laudate Dominum de coelis, motet à grand choeur arrangé dans le concerto du printemps de Vivaldi Dall’Abaco Concerto à più istrumenti in G Major, Op. 6 No. 5 Vivaldi Dixit Dominus, RV 595 S Y D NEY City Recital Hall Angel Place Friday 2, Saturday 3, Wednesday 7, Friday 9, Saturday 10 September all at 7pm Saturday 10 September at 2pm M ELBOURNE Melbourne Recital Centre Sunday 4 September at 5pm, Monday 5 September at 7pm This concert will last approximately 2 hours including interval. We request that you kindly switch off all electronic devices during the performance. C ON C ERT BROA DC A S T You can hear Celestial Vivaldi again when it's broadcast live on ABC Classic FM on Saturday 10 September at 2pm. The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra is assisted The Australian Brandenburg by the Australian Government through the Australia Orchestra is assisted by the NSW Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Government through Arts NSW. PRINCIPAL PARTNER Celestial Vivaldi At the beginning of the eighteenth century France was Europe’s super power, under the leadership of Rebel composed very little church music and only one opera, concentrating his efforts instead on songs, the charismatic and immensely powerful King Louis XIV. Calling himself the “Sun King”, giver of light, instrumental chamber works and, most successfully of all, dance music. -

Word Runneth Swiftly

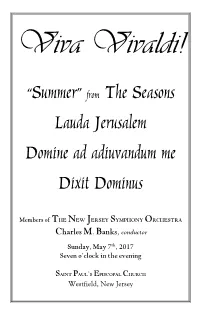

Viva Vivaldi! “Summer” from The Seasons Lauda Jerusalem Domine ad adiuvandum me Dixit Dominus Members of THE NEW JERSEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Charles M. Banks, conductor Sunday, May 7th, 2017 Seven o’clock in the evening SAINT PAUL’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH Westfield, New Jersey Welcome to SAINT PAUL’S CHURCH, to our Thirty-first Anniversary Concert, and to the twenty-fourth concert presented by Friends of Music at Saint Paul’s. We hope that you enjoy your evening. Please help others enjoy the concert by silencing all noise-making electronic devices. Summer from “The Seasons” RV 315 Antonio Lucio Vivaldi 1678 - 1741 Please hold applause until the conclusion of each work. I. ALLEGRO MÀ NON MOLTO II. ADAGIO III. PRESTO Brennan Sweet, violin Lauda Jerusalem RV 609 Mary Lynne Nielsen & Lyssandra Stephenson, sopranos Lauda Jerusalem Dominum. Lauda Deum tuum Sion. Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem. Praise thy God, O Sion. Quoniam confortavit seras portarum tuarum et benedixit filiis tuis in te. Because he hath strengthened the bolts of thy gates, he hath blessed thy children within thee. Qui posuit fines tuos pacem et adipe frumenti satiat te. Who hath placed peace in thy borders, and filleth thee with the fat of corn. Qui emittit eloquiam suum terrae, velociter currit sermo eius. Who sendeth forth his speech to the earth, his word runneth swiftly. Qui datnivem sicut lanam, nebulam sicut cinerem spargit. Who giveth snow like wool, scattereth mists like ashes. Mittit cristal suam sicut buccellas, ante faciem frigoris eius quis sustinebit? He sendeth his crystal like morsels: who shall stand before the face of his cold? Emittet verbum suum, et liquefaciet ea, flabit spiritus eius, et fluent aquae. -

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag. -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Ospedale della Pietà in Venice Opernhaus Prag Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Complete Opera – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Index - Complete Operas by Antonio Vivaldi Page Preface 3 Cantatas 1 RV687 Wedding Cantata 'Gloria e Imeneo' (Wedding cantata) 4 2 RV690 Serenata a 3 'Mio cor, povero cor' (My poor heart) 5 3 RV693 Serenata a 3 'La senna festegiante' 6 Operas 1 RV697 Argippo 7 2 RV699 Armida al campo d'Egitto 8 3 RV700 Arsilda, Regina di Ponto 9 4 RV702 Atenaide 10 5 RV703 Bajazet - Il Tamerlano 11 6 RV705 Catone in Utica 12 7 RV709 Dorilla in Tempe 13 8 RV710 Ercole sul Termodonte 14 9 RV711 Farnace 15 10 RV714 La fida ninfa 16 11 RV717 Il Giustino 17 12 RV718 Griselda 18 13 RV719 L'incoronazione di Dario 19 14 RV723 Motezuma 20 15 RV725 L'Olimpiade 21 16 RV726 L'oracolo in Messenia 22 17 RV727 Orlando finto pazzo 23 18 RV728 Orlando furioso 24 19 RV729 Ottone in Villa 25 20 RV731 Rosmira Fedele 26 21 RV734 La Silvia (incomplete) 27 22 RV736 Il Teuzzone 27 23 RV738 Tito Manlio 29 24 RV739 La verita in cimento 30 25 RV740 Il Tigrane (Fragment) 31 2 – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Preface In 17th century Italy is quite affected by the opera fever. The genus just newly created is celebrated everywhere. Not quite. For in Romee were allowed operas for decades heard exclusively in a closed society. The Papal State, who wanted to seem virtuous achieved at least outwardly like all these stories about love, lust, passions and all the ancient heroes and gods was morally rather questionable. -

Seznamy, Vysvětlivky, Rejstříky a Autorovo Slovo Na Závěr

SEZNAMY, VYSVĚTLIVKY, REJSTŘÍKY A AUTOROVO SLOVO NA ZÁVĚR ORIENTAČNÍ PŘEHLED DÍLA ANTONIA VIVALDIHO Orientační přehled díla Antonia Vivaldiho Dílo Antonia Vivaldiho je velmi rozsáhlé. Není možno, abychom v naší knize uváděli úplný výčet skladatelových děl. Zájemce o ně se ovšem může orientovat v oficiálním seznamu Vivaldiho kompozic v díle Peter Ryom, Verzeichnis der Werke Antonio Vivaldis (RV), Kleine Ausgabe. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig: 1. vydání 1974, 2. vydání 1979. – Antonio Fanna, Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). Cata- logo Numerico-Tematico delle Opere Strumentali. Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi. Fondato da Antonio Fanna. Edizioni Ricordi, G. Ricordi & C. s.p.a. Milano 1968, uvádí všechny Vivaldiho nástrojové stavby s původními italskými názvy, infor- muje o dedikacích, programních označeních děl, nových (tedy dnes soudobých) vydáních apod. Z Fanny se například dovídáme, že Vivaldi psal Koncerty pro housle Koncerty pro violu Koncerty pro violoncello Koncerty pro housle s jinými sólisty na smyčcové nástroje Koncerty pro mandolínu Koncerty pro flétnu Koncerty pro fagot Koncerty pro trubku (tromba) Koncerty pro roh (corno) Koncerty pro smyčcové nástroje Koncerty pro rozmanité soubory Sonáty pro housle Sonáty pro violoncello Sonáty pro dechové nástroje Sonáty pro rozmanité soubory přičemž Fanna také uvádí uložení nástrojových děl v těchto knihovnách: Biblio- teca Nazionale, Torino, 295 děl; Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica, Napoli, 3 díla; Biblioteca Querini Stampalia, Venezia, 1 dílo; Sächsische Landesbibliothek -

A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico During the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Valenzuela, Eladio III, "A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2797. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2797 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS ELADIO VALENZUELA III Department of Music APPROVED: ____________________________________ William McMillan, D.A., CHAIR ____________________________________ Elisa Fraser Wilson, D.M.A. ____________________________________ Curtis Tredway, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Allan D. McIntyre, M.Ed. _______________________________ Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS BY ELADIO VALENZUELA III, B.M., M.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS EL PASO MAY 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I want to thank God for the patience it took to be able to manage this project, my work, and my family life. -

Venice Baroque Orchestra: Vivaldi's Juditha Triumphans

PHOTO BY MATTEODA FINA VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA: VIVALDI’S JUDITHA TRIUMPHANS Saturday, February 4, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA 300TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR OF VIVALDI’S ORATORIO JUDITHA TRIUMPHANS Andrea Marcon, music director and conductor Delphine Galou, Juditha Mary-Ellen Nesi, Holofernes Ann Hallenberg, Vagaus Francesca Ascioti, Ozias Silke Gäng, Abra Women of the University of Illinois Chamber Singers Andrew Megill, director Antonio Vivaldi Juditha triumphans, RV 644 (1716) (1678-1741) Devicta Holofernis barbarie Sacrum militare oratorium Oratorio in two parts, presented with one 20-minute intermission. Juditha triumphans, commissioned by the Republic of Venice to celebrate the naval victory over the Ottoman Empire at Corfu in 1716, portrays the dramatic story of the Hebrew woman Judith overcoming the invading Assyrian general Holofernes and his army. The Venice Baroque Orchestra is suported by the Fondazione Cassamarca in Treviso, Italy. The Venice Baroque Orchestra appears by arrangement with: Alliance Artist Management 5030 Broadway, Suite 812 New York, NY 10034 www.allianceartistmanagement.com 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. * JOAN & PETER HOOD Sixteen Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships * PAT & ALLAN TUCHMAN Five Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO 3 * * JAMES ECONOMY ALICE & JOHN PFEFFER Special Support of Classical Music Nineteen Previous Sponsorships One Season Sponsorship * * THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE MARLYN RINEHART JUDITH & RICHARD SHERRY & NELSON BECK Nine Previous Sponsorships KAPLAN First-Time Sponsors First-Time Sponsors * * CAROLYN G. -

Dixit Dominus RV 595 Antonio Vivaldi Obsah 1

Dixit Dominus RV 595 Antonio Vivaldi Obsah 1. Antonio Vivaldi • Ţivotopis • Michael Talbot • Katalogy Vivaldiho děl 2. Dixit Dominus • Text • Dixit Dominus RV 595 • Části • Tecum principium 3. Zdroje Antonio Vivaldi 4. března 1678 Benátky – 28. července 1741 Vídeň • Oficiálně pokřtěn 6. března • Barokní kněz, skladatel a houslista • Talent a základy pro hru na housle získal nejspíše od svého otce – Giovanna Battisty – který působil mimo jiné i v bazilice sv. Marka v Benátkách • Je moţné, ţe Antonia vyučoval i tehdejší meastro di capella v bazilice sv. Marka – Giovanni Legrenzi Ţivotopis – pokračování • 1693 – 1703 – studium teologie a vysvěcení na kněze • od 9/1703 s přestávkami působil v sirotčinci Pio Ospedale della Pietà v Benátkách, pro který napsal řadu skladeb – například RV 644 Juditha triumphans • od 4/1718 – 1720 maestro di cappella da camera na dvoře mantovského vévody Filipa Hesenského • Po krátkém návratu do Benátek působil i v Římě a nadále komponoval pro sirotčinec • 1726 – 1728 skladatel a impresário v San Angelo a rovněţ působil jako maestro di capella in Italia pro hraběte Václava z Morzinu • 1729 – 1731 cestoval s otcem po Evropě • od 1740 Před koncem ţivota usiloval o post dvorního skladatele císaře Karla VI Michael Talbot • britský muzikolog a skladatel – zaměřuje se na italskou barokní hudbu a systematicky zpracovává skladatele Antonia Vivaldiho a Tommase Albinoniho. • Díky jeho bádání vznikla řada různých knih a publikací, například: Antonio Vivaldi: a Guide to Research (New York, 1988) Venetian Music in the Age of Antonio Vivaldi (Aldershot, 1999) Wenzel von Morzin as a Patron of Antonio Vivaldi’, Johann Friedrich Fasch und der italienische Stil, ed. -

MODO ANTIQUO Federico Maria Sardelli, Direzione SELVA MORALE E SPIRITUALE Di Claudio Monteverdi

Sabato 14 maggio Chiesa S. Marcellino ore 21.00 MODO ANTIQUO Federico Maria Sardelli, direzione SELVA MORALE E SPIRITUALE di Claudio Monteverdi Concerto di inaugurazione MODO ANTIQUO Federico Maria Sardelli, flauto dritto Raffaele Tiseo, Paolo Cantamessa, violini Pasquale Lepore, violetta Valeria Brunelli, violoncello Daniele Rosi, violone Judith Pacquier, cornetto Andrea Angeloni, trombone tenore Danilo Tamburo, trombone basso Andrea Coen, organo Simone Vallerotonda, tiorba Roberta Mameli, soprano Antonio Giovannini, alto Alberto Allegrezza, tenore primo Paolo Fanciullacci, tenore secondo Salvo Vitale, basso direzione Federico Maria Sardelli SELVA MORALE E SPIRITUALE Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) Beatus Vir (primo) a 6 voci con istromenti (da Selva morale, e spirituale, Venezia 1641) Giovanni Paolo Cima (c. 1570 – 1622) Sonata a 3 (da Concerti ecclesiastici, Milano 1610) Claudio Monteverdi Confitebor tibi, Domine (terzo) ‘alla francese’ a 5 voci (da Selva morale) Giovanni Gabrieli (1557 – 1612) Canzon a 5 (da Canzoni et sonate, Venezia 1615 ) Claudio Monteverdi Confitebor tibi, Domine (secondo) a canto solo e 2 violini (da Messa a quattro voci et salmi concertati, Venezia 1650) Dario Castello ( ? – entro il 1658) Sonata prima a soprano solo (da Sonate concertate in stil moderno, Libro II, Venezia 1640) Claudio Monteverdi Cantate Domino a 6 voci (da Libro primo de mottetti in lode d’Iddio nostro Signore, Venezia 1620) *** Claudio Monteverdi Laetatus sum a 5 voci (da Messa a quattro voci et salmi) Dario Castello Sonata quarta (da Sonate