Sacred Music Volume 105 Number 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus Hwv 232 Dixit Dominus Rv 807 in Furore Iustissimae Irae Rv 626

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus hwv 232 Dixit Dominus rv 807 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626 La Nuova Musica Lucy Crowe soprano dir. DAVID BATES 1 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Dixit Dominus rv 807 1 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 1’51 2 Donec ponam inimicos tuos (chorus) 3’34 3 Virgam virtutis tuae (soprano I) 3’06 4 Tecum principium in die virtutis (tenor I & II) 2’08 5 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’12 6 Dominus a dextris tuis (tenor I) 1’54 7 Judicabit in nationibus (chorus) 2’48 8 De torrente in via bibet (countertenor) 3’20 9 Gloria Patri, et Filio (soprano I & II) 2’27 10 Sicut erat in principio (chorus) 0’33 11 Amen (chorus) 2’47 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626* 12 In furore iustissimae (aria) 4’55 13 Miserationem Pater piissime (recitative) 0’39 14 Tunc meus fletus evadet laetus (aria) 6’58 15 Alleluia 1’28 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759) Dixit Dominus hwv 232 16 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 5’49 17 Virgam virtutis tuae (countertenor) 2’49 18 Tecum principium in die virtutis (soprano I) 3’31 19 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’37 20 Tu es sacerdos in aeternum (chorus) 1’19 21 Dominus a dextris tuis (SSTTB & chorus) 7’32 22 De torrente in via bibet (soprano I, II & chorus) 3’55 23 Gloria Patri, et Filio (chorus) 6’33 La Nuova Musica *with Lucy Crowe soprano 12-15 DAVID BATES director Anna Dennis, Helen-Jane Howells, Augusta Hebbert, Esther Brazil, sopranos Christopher Lowrey, countertenor Simon Wall, Tom Raskin, tenors James Arthur, bass 2 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi Dixit Dominus ithin the Roman Catholic liturgy Psalm 109 aria in Vivaldi’s opera La fida ninfa (1732). -

Concert Season 34

Concert Season 34 REVISED CALENDAR 2020 2021 Note from the Maestro eAfter an abbreviated Season 33, VoxAmaDeus returns for its 34th year with a renewed dedication to bringing you a diverse array of extraordinary concerts. It is with real pleasure that we look forward, once again, to returning to the stage and regaling our audiences with the fabulous programs that have been prepared for our three VoxAmaDeus performing groups. (Note that all fall concerts will be of shortened duration in light of current guidelines.) In this year of necessary breaks from tradition, our season opener in mid- September will be an intimate Maestro & Guests concert, September Soirée, featuring delightful solo works for piano, violin and oboe, in the spacious and acoustically superb St. Katharine of Siena Church in Wayne. Vox Renaissance Consort will continue with its trio of traditional Renaissance Noël concerts (including return to St. Katharine of Siena Church) that bring you back in time to the glory of Old Europe, with lavish costumes and period instruments, and heavenly music of Italian, English and German masters. Ama Deus Ensemble will perform five fascinating concerts. First is the traditional December Handel Messiah on Baroque instruments, but for this year shortened to 80 minutes and consisting of highlights from all three parts. Then, for our Good Friday concert in April, a program of sublime music, Bach Easter Oratorio & Rossini Stabat Mater; in May, two glorious Beethoven works, the Fifth Symphony and the Missa solemnis; and, lastly, two programs in June: Bach & Vivaldi Festival, as well as our Season 34 Grand Finale Gershwin & More (transplanted from January to June, as a temporary break from tradition), an exhilarating concert featuring favorite works by Gershwin, with the amazing Peter Donohoe as piano soloist, and also including rousing movie themes by Hans Zimmer and John Williams. -

1 Freitag, 18. Dezember 2015 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik – Neue Cds

1 Freitag, 18. Dezember 2015 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik – Neue CDs: Vorgestellt von Susanne Stähr Die maskierte Violine Antonio Vivaldi: Teatro alla moda Violinkonzerte RV 228, 282, 313, 314a, 316, 322, 323, 372a und 391; Sinfonia „L„Olimpiade”; Ballo primo de “Arsilda Refina di Ponto” Gli Incogniti, Amandine Beyer (Violine und Leitung) HMC 902221 Frau Musicas Himmelschöre Antonio Vivaldi: Geistliche Werke Gloria RV 589; Laetatus sum RV 607; Magnificat RV 610a; Lauda Jerusalem RV 609 Le Concert Spirituel, Hervé Niquet (Leitung) Alpha 222 Du angenehme Nachtigall Birds: Vögel in der Barockmusik Werke von Rameau, Händel, Arne, Vivaldi, Keiser, Couperin u.a. Dorothee Mields (Sopran), Stefan Temmingh (Blockflöte), The Genteman‟s Band, La Folia Barockorchester Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 88875141202 Atemloser Schöngesang Julia Lezhneva: Händel Frühe italienische Werke Julia Lezhneva (Sopran), Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (Leitung) Decca 478 9230 „Gross Wunderding sich bald begab“ A Wondrous Mystery Renaissancemusik zu Weihnachten Werke von Clemens non Papa, Johannes Eccard, Jacobus Gallus, Hans Leo Hassler, Hieronymus Praetorius, Michael Praetorius und Melchior Vulpius Stile Antico HMU 807575 Fürs Gemüt O heilige Nacht Romantische Chormusik zur Weihnachtszeit Werke von Franz Wüllner, Johannes Brahms, August von Othegraven, Gustav Schreck, Carl Loewe, Carl Gottlob Reißiger, Robert Fuchs, Max Bruch, Max Reger und Carl Reinthaler Dresdner Kammerchor, Hans-Christoph Rademann (Leitung) Carus 83.392 Am Mikrophon begrüßt Sie herzlich: Susanne Stähr. Sechsmal werden wir noch wach – doch was gibt es bis dahin nicht noch alles zu erledigen! Festtagseinkäufe, Weihnachtsbäckerei, letzte Geschenke, die besorgt werden wollen … Aber vielleicht können wir Ihnen wenigstens dabei helfen, mit ein paar CD-Empfehlungen nämlich. Sechs neue Platten möchte ich Ihnen gleich vorstellen: passend zur Saison mit viel Barockmusik, mit himmlischen Chören und englischen Stimmen. -

Marian Stations of the Cross

MARIAN STATIONS OF THE CROSS ST. LOUISE PARISH GATHERING SONG At The Cross Her Station Keeping (Stabat Mater Dolorosa) 1. At the cross her station keeping, 3. Let me share with thee his pain, Stood the mournful Mother weeping, Who for all my sins was slain, Close to Jesus to the last. Who for me in torment died. 2.Through her heart, his sorrow sharing, 4. Stabat Mater dolorósa All his bitter anguish bearing, Juxta crucem lacrimósa Now at length the sword has passed. Dumpendébat Fílius. Text: 88 7; Stabat Mater dolorosa; Jacapone da Todi, 1230-1306; tr. By Edward Caswall, 1814-1878, alt. OneLicense #U9879, LicenSingOnline FIRST STATION SECOND STATION L: Jesus is condemned to death L: Jesus carries his Cross All: The more I belong to God the more I will be condemned. (Matthew 5:10) All: I must carry the pain that is uniquely mine if I want to be a follower of Jesus. L: We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. (Matthew 27:28-31) (GENUFLECT) L: We adore You… (GENUFLECT) All: Because by your holy Cross You have redeemed the world. All: Because by your holy Cross... L This can’t be happening…. L: I look at my Son… All: Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women and blessed All: Hail Mary… is the fruit of your womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and Sing: Remember your love and your faithfulness, at the hour of our death. Amen O Lord. -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

TCB Groove Program

www.piccolotheatre.com 224-420-2223 T-F 10A-5P 37 PLAYS IN 80-90 MINUTES! APRIL 7- MAY 14! SAVE THE DATE! NOVEMBER 10, 11, & 12 APRIL 21 7:30P APRIL 22 5:00P APRIL 23 2:00P NICHOLS CONCERT HALL BENITO JUAREZ ST. CHRYSOSTOM’S Join us for the powerful polyphony of MUSIC INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO COMMUNITY ACADEMY EPISCOPAL CHURCH G.F. Handel's As pants the hart, 1490 CHICAGO AVE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER 1424 N DEARBORN ST. EVANSTON, IL 60201 1450 W CERMAK RD CHICAGO, IL 60610 Domenico Scarlatti's Stabat mater, TICKETS $10-$40 CHICAGO, IL 60608 TICKETS $10-$40 and J.S. Bach's Singet dem Herrn. FREE ADMISSION Dear friends, Last fall, Third Coast Baroque’s debut series ¡Sarabanda! focused on examining the African and Latin American folk music roots of the sarabande. Today, we will be following the paths of the chaconne, passacaglia and other ostinato rhythms – with origins similar to the sarabande – as they spread across Europe during the 17th century. With this program that we are calling Groove!, we present those intoxicating rhythms in the fashion and flavor of the different countries where they gained popularity. The great European composers wrote masterpieces using the rhythms of these ancient dances to create immortal pieces of art, but their weight and significance is such that we tend to forget where their origins lie. Bach, Couperin, and Purcell – to name only a few – wrote music for highly sophisticated institutions. Still, through these dance rhythms, they were searching for something similar to what the more ancient civilizations had been striving to attain: a connection to the spiritual world. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

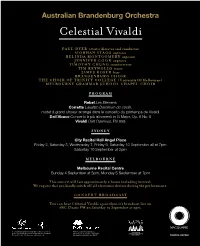

Celestial Vivaldi

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Celestial Vivaldi PAUL DYER artistic director and conductor SIOBHAN STAGG soprano BELINDA MONTGOMERY soprano JENNIFER COOK soprano TIMOTHY CHUNG sountertenor TIM REYNOLds tenor JAMES ROSER bass BRANDENBURG CHOIR THE CHOIR OF TRINITY COLLEGE (University Of Melbourne) MELBOURNE GRAmmAR SCHOOL CHAPEL CHOIR P ROGRA M Rebel Les Elémens Corrette Laudate Dominum de coelis, motet à grand choeur arrangé dans le concerto du printemps de Vivaldi Dall’Abaco Concerto à più istrumenti in G Major, Op. 6 No. 5 Vivaldi Dixit Dominus, RV 595 S Y D NEY City Recital Hall Angel Place Friday 2, Saturday 3, Wednesday 7, Friday 9, Saturday 10 September all at 7pm Saturday 10 September at 2pm M ELBOURNE Melbourne Recital Centre Sunday 4 September at 5pm, Monday 5 September at 7pm This concert will last approximately 2 hours including interval. We request that you kindly switch off all electronic devices during the performance. C ON C ERT BROA DC A S T You can hear Celestial Vivaldi again when it's broadcast live on ABC Classic FM on Saturday 10 September at 2pm. The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra is assisted The Australian Brandenburg by the Australian Government through the Australia Orchestra is assisted by the NSW Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Government through Arts NSW. PRINCIPAL PARTNER Celestial Vivaldi At the beginning of the eighteenth century France was Europe’s super power, under the leadership of Rebel composed very little church music and only one opera, concentrating his efforts instead on songs, the charismatic and immensely powerful King Louis XIV. Calling himself the “Sun King”, giver of light, instrumental chamber works and, most successfully of all, dance music. -

Bach Vivaldi: Gloria - Caldara: Stabat Mater - Bach: Magnificat Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bach Vivaldi: Gloria - Caldara: Stabat Mater - Bach: Magnificat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Vivaldi: Gloria - Caldara: Stabat Mater - Bach: Magnificat Country: UK Released: 1992 Style: Classical, Baroque MP3 version RAR size: 1627 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1860 mb WMA version RAR size: 1357 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 513 Other Formats: DXD WAV AAC VQF APE WMA MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits Gloria In D Major Rv. 589 Alto Vocals – Alison BrownerComposed By – Antonio VivaldiSoprano Vocals – Lynda Russell 1 Gloria In Excelsis Deo (Chorus) 2:28 2 Et In Terra Pax Hominibus (Chorus) 4:53 3 Laudamus Te (Sopranos I & Ii) 2:12 4 Gratias Agimus Tibi (Chorus) 0:27 5 Propter Magnam Gloriam (Chorus) 0:53 6 Domine Deus (Soprano) 3:31 7 Domine Fili Unigenite (Chorus) 2:10 8 Domine Deus, Agnus Dei (Alto & Chorus) 4:09 9 Qui Tollis Peccata Mundi (Chorus) 1:04 10 Qui Sedes Ad Dexteram (Alto) 2:06 11 Quoniam Tu Solus Sanctus (Chorus) 0:45 12 Cum Sancto Spiritu (Chorus) 2:43 Stabat Mater Alto Vocals – Caroline TrevorComposed By – Antonio Caldara 13 Stabat Mater Dolorosa (Chorus & Soli) 2:35 14 Quis Est Homo, Qui Non Fleret? (Soli) 3:18 15 Sancta Mater (Chorus & Tenor) 2:18 16 Fac Me Tecum Pie Flere (Chorus & Soli) 1:47 17 Virgo Virginum Praeclara (Chorus) 1:28 18 Fac Ut Portem (Alto) 1:17 19 Flammis Ne Urar Succensus (Soprano & Bass) 0:59 20 Christe, Cum Sit Hinc Exire (Chorus) 1:53 21 Fac Ut Animae Donetur (Chorus) 1:29 Magnificat In D Major, BWV 243 Alto Vocals – Alison BrownerSoprano Vocals – Lynda Russell 22 Magnificat Anima Mea (Chorus) 2:52 23 Et Exultavit (Soprano Ii) 2:23 24 Quia Respexit (Soprano I) 2:12 25 Omnes Generationes (Chorus) 1:11 26 Quia Fecit Mihi Magna (Bass) 2:10 27 Et Misericordia (Alto, Tenor) 3:36 28 Fecit Potentiam (Chorus) 1:51 29 Deposuit Potentes (Tenor) 1:59 30 Esurientes (Alto) 2:55 31 Suscepit Israel (Chorus) 2:08 32 Sicut Locutus Est (Chorus) 1:32 33 Gloria (Chorus) 2:20 Companies, etc. -

Word Runneth Swiftly

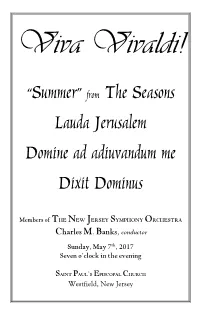

Viva Vivaldi! “Summer” from The Seasons Lauda Jerusalem Domine ad adiuvandum me Dixit Dominus Members of THE NEW JERSEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Charles M. Banks, conductor Sunday, May 7th, 2017 Seven o’clock in the evening SAINT PAUL’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH Westfield, New Jersey Welcome to SAINT PAUL’S CHURCH, to our Thirty-first Anniversary Concert, and to the twenty-fourth concert presented by Friends of Music at Saint Paul’s. We hope that you enjoy your evening. Please help others enjoy the concert by silencing all noise-making electronic devices. Summer from “The Seasons” RV 315 Antonio Lucio Vivaldi 1678 - 1741 Please hold applause until the conclusion of each work. I. ALLEGRO MÀ NON MOLTO II. ADAGIO III. PRESTO Brennan Sweet, violin Lauda Jerusalem RV 609 Mary Lynne Nielsen & Lyssandra Stephenson, sopranos Lauda Jerusalem Dominum. Lauda Deum tuum Sion. Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem. Praise thy God, O Sion. Quoniam confortavit seras portarum tuarum et benedixit filiis tuis in te. Because he hath strengthened the bolts of thy gates, he hath blessed thy children within thee. Qui posuit fines tuos pacem et adipe frumenti satiat te. Who hath placed peace in thy borders, and filleth thee with the fat of corn. Qui emittit eloquiam suum terrae, velociter currit sermo eius. Who sendeth forth his speech to the earth, his word runneth swiftly. Qui datnivem sicut lanam, nebulam sicut cinerem spargit. Who giveth snow like wool, scattereth mists like ashes. Mittit cristal suam sicut buccellas, ante faciem frigoris eius quis sustinebit? He sendeth his crystal like morsels: who shall stand before the face of his cold? Emittet verbum suum, et liquefaciet ea, flabit spiritus eius, et fluent aquae. -

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag. -

Paul Collins (Ed.), Renewal and Resistance Journal of the Society

Paul Collins (ed.), Renewal and Resistance PAUL COLLINS (ED.), RENEWAL AND RESISTANCE: CATHOLIC CHURCH MUSIC FROM THE 1850S TO VATICAN II (Bern: Peter Lang, 2010). ISBN 978-3-03911-381-1, vii+283pp, €52.50. In Renewal and Resistance: Catholic Church Music from the 1850s to Vatican II Paul Collins has assembled an impressive and informative collection of essays. Thomas Day, in the foreword, offers a summation of them in two ways. First, he suggests that they ‘could be read as a collection of facts’ that reveal a continuing cycle in the Church: ‘action followed by reaction’ (1). From this viewpoint, he contextualizes them, demonstrating how collectively they reveal an ongoing process in the Church in which ‘(1) a type of liturgical music becomes widely accepted; (2) there is a reaction to the perceived in- adequacies in this music, which is then altered or replaced by an improvement ... The improvement, after first encountering resistance, becomes widely accepted, and even- tually there is a reaction to its perceived inadequacies—and on the cycle goes’ (1). Second, he notes that they ‘pick up this recurring pattern at the point in history where Roman Catholicism reacted to the Enlightenment’ (3). He further contextualizes them, revealing how the pattern of action and reaction—or renewal and resistance—explored in this particular volume is strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, an attempt to look to the power of reason as a more beneficial guide for humanity than the authority of religion and perceived traditions (4). As the Enlightenment