LOST PINES CHAPTER Texas Master Naturalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconnaissance Survey of the Indian Hills Subdivision Enid, Garfield County, Oklahoma

FINAL RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY OF THE INDIAN HILLS SUBDIVISION ENID, GARFIELD COUNTY, OKLAHOMA by Sherry N. DeFreece Emery, M.S., MArch Adapt ǀ re:Adapt Preservation and Conservation, LLC 1122 Jackson Street #518 Dallas, Texas 75202 Prepared for City of Enid, Oklahoma 401 West Owen K. Garriott Road P.O. Box 1768 Enid, OK 73702 Adapt ǀ re:Adapt Project Number 2015007 June 2016 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Reconnaissance Survey of the Indian Hills Subdivision FINAL Report ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF SUPPORT The activity that is the subject of this Reconnaissance Survey has been financed with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Nondiscrimination Statement This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act or 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Chief, Office of Equal Opportunity United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 1201 Eye Street, NW (2740) Washington, D.C. 20005 June 2016 iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Reconnaissance Survey of the Indian Hills Subdivision FINAL Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. -

Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: the Ih Story and the Legend Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Booth Library Programs Conferences, Events and Exhibits Spring 2015 Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend Booth Library Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Booth Library, "Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend" (2015). Booth Library Programs. 15. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Events and Exhibits at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth Library Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quanah & Cynthia Ann Parker: The History and the Legend e story of Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker is one of love and hate, freedom and captivity, joy and sorrow. And it began with a typical colonial family’s quest for a better life. Like many early American settlers, Elder John Parker, a Revolutionary War veteran and Baptist minister, constantly felt the pull to blaze the trail into the West, spreading the word of God along the way. He led his family of 13 children and their descendants to Virginia, Georgia and Tennessee before coming to Illinois, where they were among the rst white settlers of what is now Coles County, arriving in c. 1824. e Parkers were inuential in colonizing the region, building the rst mill, forming churches and organizing government. One of Elder John’s many grandchildren was Cynthia Ann Parker, who was born c. -

County Economic Southeast Colorado Observatory Development Commission Inc

PIERRE AUGER COSMIC RAY BACA COUNTY ECONOMIC SOUTHEAST COLORADO OBSERVATORY DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION INC. ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT, INC. The Pierre Auger Project is a collaboration of 17 countries and Baca County Community Foundation, (BCCF) was Created in 1986 by the counties of Baca, Bent, Crowley, Kiowa more than 350 scientists coming together to study one of the founded to promote responsible, sustainable development and Prowers, SECED administers programs in cooperation greatest mysteries in science today, ultra-high energy cosmic and growth through the expansion and or retention of with our 24 members, comprised of local governments. rays, the universe’s highest energy particles. The Auger the county’s agricultural business. Bordering Kansas, SECED provides incentives and develops promotional Observatory is located at two sites: the completed southern Oklahoma, and New Mexico, Baca County is a farming and ranching community located in the very southeast activities that will market and advertise the advantages of hemisphere site is located in Malargue, Argentina and the corner of Colorado. It is rich in history, natural resources locating a business in the Southeast Colorado area, create a northern hemisphere site will be located in a region of 4,000 and wildlife. Baca County is in an enterprise zone that positive identity, encourage retention and expansion of existing square miles in the counties of Baca, Bent, Kiowa and Prowers. offers tax credits as well as other assistance in relocation business, promote redevelopment, expand the region’s tourism Photo by SECED, Inc. With access to both sites, scientists will be able to “view” the entire to Southeastern Colorado. industry, attract new businesses, and generally enhance the universe and to study the entire sky. -

Fort Stockton Public Library Community Outreach Plan

FORT STOCKTON PUBLIC LIBRARY COMMUNITY OUTREACH PLAN Prepared by: Elva Valadez Date: May 24, 2012 500 N. Water Ft Stockton, TX 79735 (432) 336-3374 http://www.fort-stockton.lib.tx.us/ This plan was created through the University of North Texas PEARL project. Funding for PEARL (Promoting and Enhancing the Advancement of Rural Libraries) provided by the Robert and Ruby Priddy Charitable Trust. Fort Stockton Public Library Community Outreach Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Community Profile Narrative 4 Library Profile Narrative 5 Library Vision, Mission, Goals and Objectives 6 Outreach Program 9 Detailed Action Plan 10 Appendix: Library Evaluation Form 13 2 Fort Stockton Public Library Community Outreach Plan Outreach Plan Introduction Fort Stockton, Texas, is located along the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. It is the county seat of Pecos County. The town is on Interstate 10, approximately 90 miles southwest of Odessa. The city that was later to be named Fort Stockton grew up around Comanche Springs, at one time the third largest source of spring water in Texas. It was near Camp Stockton, established in 1858, and named for Robert Field Stockton. Comanche Springs was a favorite stop at the cross roads of the Comanche Trail to Chihuahua, the San Antonio-El Paso Road, the Butterfield Overland Mail Route, and the San Antonio-Chihuahua freight wagon road. The post protected travelers and settlers making use of the water supply at the springs. Historical, Current, and Future Roles of the Library Historically and currently, the library has filled many roles in the community. These include lifelong learning; free and equal access to information; community meeting place; educational and recreational materials; information assistance; local history and genealogy; formal education support; information literacy; cultural awareness; current topics and titles; gateway to information; business support; public computer access; early childhood literacy, and preschool door to learning. -

Maps of Stephen F. Austin: an Illustrated Essay of the Early Cartography of Texas

The Occasional Papers Series No. 8 A Philip Lee Phillips Map Society Publication Maps of Stephen F. Austin: An Illustrated Essay of the Early Cartography of Texas Dennis Reinhartz i The Occasional Papers A Philip Lee Phillips Map Society Publication Editorial Staff: Ralph E. Ehrenberg Managing Editor Ryan Moore Chief Editor, Design and Layout Michael Klein Editor Anthony Mullan Editor David Ducey Copy Editor Geography and Map Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. Winter 2015 The Maps of Stephen F. Austin: An Illustrated Essay of the Early Cartography of Texas Dennis Reinhartz Foreword The Philip Lee Phillips Map Society of the Library of Congress is a national support group that has been established to stimulate interest in the Geography and Map Division’s car- tographic and geographic holdings and to further develop its collections through financial dona- tions, gifts, and bequests. The Phillips Map Society publishes a journal dedicated to the study of maps and collections held in the Division known as The Occasional Papers. This install- ment focuses on the maps of Stephen F. Austin and early maps of Texas. Maps, such as those of Austin, have played a key role in the history of exploration, and we hope that this issue will stimulate intellectual exploration in maps of Texas and the American west. The Library of Congress’ holdings in these areas are remarkable and many possibilities remain to be discov- ered. The paper’s author, Dennis Reinhartz, is uniquely situated to elaborate on the maps of Stephen F. Austin. For more than three and a half decades, he was a professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington, where lectured on the history of cartography, among other interesting topics. -

Texas Pecos Trail Region

Frontier Spirit in Big Sky Country ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ igh tabletop mesas rise from wide-open prairies. Ancient rivers course through sheer limestone canyons. Cool artesian springs bubble up from deep underground and ceaseless wind sculpts sand into ever-changing dunes. Above it all stretches a sky so big you can almost reach out and touch it. This is the legendary Wild West of classic books and movies, and the real-life landscape of the Texas Pecos Trail Region. The region’s 22 West Texas counties cover almost 35,000 square miles, an area larger than a dozen average-sized U.S. states. This big land comprises an ecological transition zone at the junction of the high and rolling plains in the north, Edwards Plateau in the east, mountain basins and Chihuahuan Desert in the west and brush country in the south. For centuries, scattered Native American groups hunted buffalo and other game across the immense UTSA’s InstituteUTSA’s Cultures, of Texan #068-0154 grassland prairies. These same groups also used plant Comanche warrior resources and created large plant processing and baking features on the landscape. Dry caves and Th e front cover photo was taken at the American Airpower Heritage rock shelters in the Lower Pecos canyon lands display Museum in Midland, which houses one of the world’s largest collections native rock art and preserve material evidence of the of World War II aircraft nose art. Th ese original nose art panels are titled “Save the Girls” and represent the artistic expressions of World prehistoric lifeways. Later, Native Americans such as War II bomber pilots. -

Chapter 14 Hydrogeology of the Marathon Basin Brewster County

Chapter 14 Hydrogeology of the Marathon Basin Brewster County, Texas Richard Smith1 Introduction The Marathon Basin lies in the northeastern part of Brewster County in western Texas (fig. 14-1). The region, referred to as Trans-Pecos Texas in the literature, is in the westward-projecting part of the state that lies along the Rio Grande west of the Pecos River. Physiographically, the region is closer to Mexico and New Mexico than to the rest of Texas. It is a region of high plateaus, broad cuestas, rugged mountains, and gently sloping intermontane plains. Very little vegetation is present except in sheltered valleys and on the higher summits. This factor allows an uncluttered view of the bedrock geology. Ephemeral streams, which are little more than dry gravel beds for the vast majority of the year, gather runoff from the mountains and flow across the plains during the summer rainy season. These include Maravillas Creek, San Francisco Creek, Dugout Creek, Pena Blanca Creek, Pena Colorada Creek, and Woods Hollow Creek, to name a few. Several springs that flowed in historical times have now ceased and very little year round surface water is present in the area. The basin includes about 760 mi2 centered on the town of Marathon. The basin is bounded on the north and west by the Glass Mountains and Del Norte Mountains, respectively. On the east, the boundary is recognized at Lemons Gap between Spencer and Housetop Mountains (fig. 14-2). The southern extent of the basin basically ends at Maravillas Gap, where Maravillas Creek cuts through the southwest end of the Dagger Flat anticlinorium. -

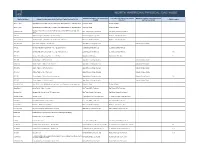

Physical Natural Gas Hub List

Gas Daily Index Reference for NG Firm Phys, Inside FERC Index Reference for NG Firm Natural Gas Intelligence Index Reference for Physical Hub Name Delivery Point Description for NG Firm Phys, FP & NG Firm Phys BS, LD1 ICE NGX Clearable? ID, GDD Phys, ID, IF NG Firm Phys, ID, NGI AB Pool (inter) Agua Blanca Pool (interstate gas only, contact White Water Midstream for applicable rates) Southwest, Waha Southwest, Waha AB Pool (intra) Agua Blanca Pool (intrastate gas only, contact White Water Midstream for applicable rates) Southwest, Waha Southwest, Waha Agua Dulce Hub (sellers' choice, intra-state gas only, contact NET Mexico for applicable Agua Dulce Hub East Texas, Houston Ship Channel East Texas, Houston Ship Channel rates) AGT-CG Algonquin Citygates (Excluding J-Lateral deliveries) Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates AGT-CG (non-G) Algonquin Citygates (Excluding J-Lateral and G-Lateral deliveries) Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates ANR-Joliet Hub ANR Pipeline Company - Joliet Hub CDP Upper Midwest, Chicago city-gates Midwest, Chicago Citygate ANR-SE American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SE Gathering Pool Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. ANR-SE-T American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SE Transmission Pool Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Yes ANR-SW American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SW Pool Midcontinent, ANR, Okla. Midcontinent, ANR, Okla. Yes APC-ANR Alliance Pipeline - ANR Interconnect Upper Midwest, Chicago -

San Elizario Crossing Project

- Office of Energy Energy Projects FederalRegulatory Commission January 2016 Comanche Trail Pipeline, LLC Docket No. CP15-503-000 San Elizario Crossing Project Environmental Assessment Washington, DC 20426 FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20426 OFFICE OF ENERGY PROJECTS In Reply Refer To: OEP/DG2E/Gas 1 Comanche Trail Pipeline, LLC San Elizario Crossing Project Docket No. CP15-503-000 TO THE PARTY ADDRESSED: The staff of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC or Commission) has prepared this Environmental Assessment (EA) of the San Elizario Crossing Project (Project) proposed by Comanche Trail Pipeline, LLC in the above-referenced docket. Comanche Trail Pipeline, LLC requests authorization to construct, operate, and maintain a new natural gas pipeline in El Paso County, Texas. The proposed San Elizario Crossing Project would involve construction of approximately 1,800 feet of FERC-jurisdictional 42-inch-diameter pipeline, installed beneath the Rio Grande River near the City of San Isidro, State of Chihuahua. The new pipeline would transport natural gas to a new delivery interconnect with pipeline facilities owned by an affiliate of Comanche Trail at the United States - Mexico border for expanding electric generation and industrial market needs in Mexico. The EA assesses the potential environmental effects of the construction and operation of the Project in accordance with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). The FERC staff concludes that approval of the proposed Project, with appropriate mitigating measures, would not constitute a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. The FERC staff mailed copies of the EA to federal, state, and local government representatives and agencies; elected officials; environmental and public interest groups; Native American tribes; potentially affected landowners and other interested individuals and groups; newspapers and libraries in the Project area; and parties to this proceeding. -

MEETING NOTICE BREWSTER COUNTY, TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION WHEN: Thursday, August 16, 2018 - 3:00 to 5:00 P.M

AGENDA MEETING NOTICE BREWSTER COUNTY, TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION WHEN: Thursday, August 16, 2018 - 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. WHERE: Judge Val Beard Office Complex Conference Room Alpine, Brewster County, Texas AGENDA: BREWSTER COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION The Brewster County Historical Commission may discuss and/or take action on any of the following items: 1. Call the meeting to order, with the Recognition and Introduction of Members and Visitors. 2. Public Comments for items not on the agenda. 3. Review of “By Laws” for the Brewster County Historical Commission. 4. Brewster County Historical Commissioners, Review the various governing rules and statutes that create the County Historical Commissions and the duties of the members as established by the State and the County Commissioners Court. 5. Review the committee assignments of the Brewster County Historical Commissioners 6. Approval of the Minutes for the May 16, 2018 meeting. 7. Report of the Auditor, Ms. Melleta Bell. 8. The plan for Brewster County “VISIONARIES IN PRESERVATION PROGRAM” is located on the THC web page. 9. The Texas Historical Commission (THC) annual reports for Brewster County were filed. Brewster County was designated as a distinguished county. 10. General report and program on Historic Texas Courthouses, Foundation for the Future. Update on funding program for the Courthouses as reported from THC. 11. Review the Junior Historian Program and the History Fair Program conducted at Sul Ross State University. A request has been made to the Brewster County Historical Commission for funding this project again this year (February 2019), to be followed by the State program in Austin. -

52-County Roundup of Holiday Events #1

52-County Roundup of Holiday Events #1: AMARILLO Christmas in the Gardens Thursday, 11/29/18-Sunday, 12/23/18 6:00 PM-8:00 PM-Nightly Amarillo Botanical Gardens 1400 Streit Dr., Amarillo, TX 79106 (806) 352-6513; [email protected] www.amarillobotanicalgardens.org Adults $5; kids 6-12, $2 Center City Electric Light Parade Friday, 11/30/18 6:00 PM-8:00 PM Downtown; start 11th Ave. & Polk St., Amarillo, TX (806) 372-6744; [email protected] www.centercity.org/lightparade Free A Winter Wonderland of lighted floats travels down neon-lighted Polk Street. Center City welcomes the holidays with a lighted parade starting at 11th Ave. & Polk St. at 6 p.m. on November 30. The parade continues down to Third Avenue and over to the Amarillo Civic Center Area for the lighting of the city of Amarillo Christmas Tree, a musical program and free visits with Santa Claus & Mrs. Claus. ZOOLights Safari (7th Annual) Saturday, 12/1/18-Sunday, 12/23/18 6-8 pm nightly Amarillo Zoo 700 Comanchero Trail, Amarillo, TX, 79107 (806) 381.7911 [email protected] www.zoo.amarillo.gov/events/zoolights General admission applies ZOOLights will be brighter and more sparkling than ever this year as this festive, family fun event returns for its 7th season. Come out Thursday thru Sunday beginning Saturday, December 1st to see thousands of holiday lights, along with displays. Plus, each weekend we will have special events to bring more of the holiday cheer. Decorate a cookie at Mrs. Claus' Kitchen, get a photo with Santa Lion or Tiger Claws, play some holiday games, and find your way through our holiday maze. -

Major and Historical Springs of Texas

TEXAS WATER DEVELOPMENT BOARD Report 189 r~ mV1SI~ri F!~E COpy I DO NOT RcM'JVE FIlOM REPORTS DIV!SION FILES, I MAJOR AND HIST,ORICAL SPRINGS OF TEXAS March 1975 TEXAS WATER DEVELOPMENT BOARD REPORT 189 MAJOR AND HISTORICAL SPRINGS OF TEXAS By Gunnar Brune March 1975 TEXAS WATER DEVELOPMENT BOARD John H. McCoy, Chairman Robert B. Gilmore, Vice Chairman W. E. Tinsley Milton Potts Carl Illig A. L. Black Harry P. Burleigh, Executive Director Authorization for use or reproduction of any original material contained in this publication, i.e., not obtained from other sources, is freely granted. The Board would appreciate acknowledgement. Published and distributed by the Texas Water Development Board Post Office Box 13087 Austin, Texas 78711 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION 3 Purpose of Study. 3 Saline Springs. 3 Method of Study . 3 Spring Numbering System. 4 Acknowledgements. 5 Classification of Springs 5 IMPORTANCE OF TEXAS SPRINGS. 5 Historical Significance 5 Size of Springs 9 GEOLOGIC SETTING . 11 Spring Aquifers . 11 Typical Geologic Settings of Springs 12 QUALITY OF SPRING WATERS 15 DECLINE OF SPRINGS 22 Prehistoric Setting 22 Causes of Spring Decline 22 Some Examples ... 25 Texas Water Law as Relating to Springs 28 DETAILED INFORMATION ON INDIVIDUAL SPRINGS. 30 Bandera County 30 Bastrop County 31 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont'd.) Page Baylor County 31 Bell County 31 Bexar County . 32 Blanco County 34 Bosque County 34 Bowie County. 34 Brewster County . 35 Briscoe County 35 Burleson County . 35 Burnet County 35 Cass County 36 Cherokee County 36 Clay County .. 37 Collingsworth County 37 Comal County 37 Crockett County 40 Crosby County 40 Culberson County 40 Dallam County 40 Dallas County.