Oversight Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leadership PAC $6000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley

L3Harris Technologies, Inc. PAC 2020 Cycle Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA American Security PAC Rep. Mike Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $6,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Byrne (R) Congressional District 1 $2,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Doug Jones for Senate Committee Sen. Doug Jones (D) United States Senate $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 2 $3,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Mike Rogers (R) Congressional District 3 $11,000 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Aderholt (R) Congressional District 4 $3,500 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Sewell (D) Congressional District 7 $10,000 Together Everyone Realizes Real Impact Rep. Terri Sewell (D) Leadership PAC $5,000 (TERRI) PAC ALASKA Alaskans For Dan Sullivan Sen. Dan Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Lisa Murkowski For US Senate Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) United States Senate $5,000 ARIZONA David Schweikert for Congress Rep. David Schweikert (R) Congressional District 6 $2,500 Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben Gallego (D) Congressional District 7 $3,000 Kirkpatrick for Congress Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Congressional District 2 $7,000 McSally for Senate, Inc Sen. Martha McSally (R) United States Senate $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D) United States Senate $5,000 Stanton for Congress Rep. Greg Stanton (D) Congressional District 9 $8,000 Thunderbolt PAC Sen. Martha McSally (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 ARKANSAS Crawford for Congress Rep. Rick Crawford (R) Congressional District 1 $2,500 Womack for Congress Committee Rep. Steve Womack (R) Congressional District 3 $3,500 CALIFORNIA United for a Strong America Rep. -

Organizational Meeting for the 117Th Congress

i [H.A.S.C. No. 117–1] ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING FOR THE 117TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MEETING HELD FEBRUARY 3, 2021 U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 43–614 WASHINGTON : 2021 COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS ADAM SMITH, Washington, Chairman JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MIKE ROGERS, Alabama RICK LARSEN, Washington JOE WILSON, South Carolina JIM COOPER, Tennessee MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio JOE COURTNEY, Connecticut DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado JOHN GARAMENDI, California ROBERT J. WITTMAN, Virginia JACKIE SPEIER, California VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri DONALD NORCROSS, New Jersey AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia RUBEN GALLEGO, Arizona MO BROOKS, Alabama SETH MOULTON, Massachusetts SAM GRAVES, Missouri SALUD O. CARBAJAL, California ELISE M. STEFANIK, New York ANTHONY G. BROWN, Maryland, SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee RO KHANNA, California TRENT KELLY, Mississippi WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts MIKE GALLAGHER, Wisconsin FILEMON VELA, Texas MATT GAETZ, Florida ANDY KIM, New Jersey DON BACON, Nebraska CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania JIM BANKS, Indiana JASON CROW, Colorado LIZ CHENEY, Wyoming ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan JACK BERGMAN, Michigan MIKIE SHERRILL, New Jersey MICHAEL WALTZ, Florida VERONICA ESCOBAR, Texas MIKE JOHNSON, Louisiana JARED F. GOLDEN, Maine MARK E. GREEN, Tennessee ELAINE G. LURIA, Virginia, Vice Chair STEPHANIE I. BICE, Oklahoma JOSEPH D. MORELLE, New York C. SCOTT FRANKLIN, Florida SARA JACOBS, California LISA C. MCCLAIN, Michigan KAIALI’I KAHELE, Hawaii RONNY JACKSON, Texas MARILYN STRICKLAND, Washington JERRY L. CARL, Alabama MARC A. VEASEY, Texas BLAKE D. MOORE, Utah JIMMY PANETTA, California PAT FALLON, Texas STEPHANIE N. MURPHY, Florida Vacancy PAUL ARCANGELI, Staff Director ZACH STEACY, Director, Legislative Operations (II) ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING FOR THE 117TH CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES, Washington, DC, Wednesday, February 3, 2021. -

Congress of the United States Washington D.C

Congress of the United States Washington D.C. 20515 April 29, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader United States House of Representatives United States House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: As Congress continues to work on economic relief legislation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we ask that you address the challenges faced by the U.S. scientific research workforce during this crisis. While COVID-19 related-research is now in overdrive, most other research has been slowed down or stopped due to pandemic-induced closures of campuses and laboratories. We are deeply concerned that the people who comprise the research workforce – graduate students, postdocs, principal investigators, and technical support staff – are at risk. While Federal rules have allowed researchers to continue to receive their salaries from federal grant funding, their work has been stopped due to shuttered laboratories and facilities and many researchers are currently unable to make progress on their grants. Additionally, researchers will need supplemental funding to support an additional four months’ salary, as many campuses will remain shuttered until the fall, at the earliest. Many core research facilities – typically funded by user fees – sit idle. Still, others have incurred significant costs for shutting down their labs, donating the personal protective equipment (PPE) to frontline health care workers, and cancelling planned experiments. Congress must act to preserve our current scientific workforce and ensure that the U.S. -

Flfln PANETA INSTITUTE

flfln PANETA INSTITUTE The Panetta Institute fo-r Public Policy July 11, 2013 Dr. Walter Tribley Superintendent/President Monterey Peninsula College 980 Fremont Street Monterey, California 9394C Dear Walt: Thank you very much for your generosity of time and expertise as a speaker for the Panetta Institute's fourteenth annual Education for Leadership in Public Service Seminar. We deeply appreciate the dual nature of your presentation this year: background information on the challenges of your profession and the personal insights you have gained about successful leadership practices in general. This year's seminar was a great success and a significant reason for this was the time, energy and knowledge you offered. Further, it is an extraordinary opportunity for our students to hear from a person of your character and accomplishments. This next generation of leaders will surely make its share of mistakes. The advantage of leadership programs like the Institute's is that we can help prevent a repetition of the same mistakes. And, in this way, we do make the future better for our children and their children. It is our hope, then, that these student body presidents will take what they learned and apply this knowledge to their work as leaders now and in the years to come. Comments like this one from a 2013 Leadership Seminar student give credence to our optimism: "I've grown so much in this experience. The speakers have been great, the Institute has been great, and this class has been fantastic. I've learned so much about leadership, government, public policy and life. -

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

California RESTAURANT INDUSTRY at a GLANCE

California RESTAURANT INDUSTRY AT A GLANCE Restaurants are a driving force in California’s economy. They provide jobs and build careers for thousands of people, and play a vital role in local communities throughout the state. 76,201 1,830,000 Eating and drinking place Restaurant and foodservice jobs locations in California in 2018 in California in 2019 = 11% of employment in the state And by 2029, that number is projected $97.0 billion to grow by 9% Estimated sales in California’s = 164,300 additional jobs, restaurants in 2018 for a total of 1,994,300 Every dollar spent in the tableservice segment HOW DOES THE contributes $2.03 to the state economy. RESTAURANT INDUSTRY IMPACT THE Every dollar spent in the limited-service segment CALIFORNIA ECONOMY? contributes $1.75 to the state economy. FOR MORE INFORMATION: Restaurant.org • CalRest.org © 2019 National Restaurant Association. All rights reserved. California’s Restaurants JOBS AND ENTREPRENEURIAL OPPORTUNITIES IN EVERY COMMUNITY EATING AND DRINKING PLACES: Establishments Employees U.S. SENATORS in the state in the state* Dianne Feinstein (D) 76,201 1,457,000 Kamala Harris (D) EATING AND DRINKING PLACES: EATING AND DRINKING PLACES: Establishments Employees Establishments Employees U.S. REPRESENTATIVES in the state in the state* U.S. REPRESENTATIVES in the state in the state* 1 Doug LaMalfa (R) 1,212 23,180 28 Adam B. Schiff (D) 2,102 40,200 2 Jared Huffman (D) 1,735 33,166 29 Tony Cárdenas (D) 806 15,408 3 John Garamendi (D) 1,126 21,533 30 Brad Sherman (D) 1,770 33,842 4 Tom McClintock (R) 1,541 29,457 31 Pete Aguilar (D) 1,166 22,299 5 Mike Thompson (D) 1,382 26,422 32 Grace F. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

2017-2018 Political Contributions

2017-2018 Political Contributions - DeltaPAC Committee Amount Committee Amount 21ST CENTURY MAJORITY FUND 10000 CARTWRIGHT FOR CONGRESS 4000 ADAM SMITH FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE 5000 CASTOR FOR CONGRESS 2500 ADRIAN SMITH FOR CONGRESS 2500 CATHY MCMORRIS RODGERS FOR 10000 ALAMO PAC 5000 CONGRESS ALAN LOWENTHAL FOR CONGRESS 1500 CHARLIE CRIST FOR CONGRESS 1000 ALASKANS FOR DON YOUNG INC. 2500 CHC BOLD PAC 5000 AMERIPAC 10000 CHERPAC 1000 AMODEI FOR NEVADA 2500 CINDY HYDE-SMITH FOR US SENATE 5000 ANDRE CARSON FOR CONGRESS 1500 CITIZENS FOR JOHN RUTHERFORD 2500 ANDY BARR FOR CONGRESS, INC. 2500 CITIZENS FOR TURNER 2500 ANDY LEVIN FOR CONGRESS 1000 CITIZENS FOR WATERS 2500 ANGUS KING FOR US SENATE CAMPAIGN 5000 CITIZENS TO ELECT RICK LARSEN 10000 ANTHONY GONZALEZ FOR CONGRESS 1000 CLARKE FOR CONGRESS 5000 ARMSTRONG FOR CONGRESS 1000 CLAUDIA TENNEY FOR CONGRESS 2500 AX PAC 7500 COFFMAN FOR CONGRESS 2018 2500 BADLANDS PAC 2500 COLE FOR CONGRESS 2500 BARRAGAN FOR CONGRESS 1000 COLLINS FOR CONGRESS 11000 BELIEVE IN AMERICA PAC 5000 COLLINS FOR SENATOR 5000 BEN CARDIN FOR SENATE, INC. 2500 COMMITTEE TO ELECT STEVE WATKINS 1500 BEN CLINE FOR CONGRESS, INC. 1000 COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT HANK JOHNSON 10000 BERGMANFORCONGRESS 12500 COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LINDA SANCHEZ 5000 COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT NYDIA M. BIG SKY OPPORTUNITY PAC 2500 2500 BILL CASSIDY FOR US SENATE 2500 VELAZQUEZ TO CONGRESS BILL FLORES FOR CONGRESS 5000 COMMON VALUES PAC 5000 BILL NELSON FOR U S SENATE 7500 COMSTOCK FOR CONGRESS 2500 BILL SHUSTER FOR CONGRESS 5000 CONAWAY FOR CONGRESS 3500 -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

August 25, 2020 Vice President Michael R. Pence the White House

August 25, 2020 Vice President Michael R. Pence The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Vice President Pence: As our nation progresses deeper into the 2020 wildfire season while grappling with the COVID- 19 pandemic, we write to you in your capacity as head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force (Task Force) to immediately address the safety needs of American farmers and farmworkers. We ask the Task Force to assist agricultural stakeholders, along with state and local governments, with the timely procurement of safety equipment, including N-95 masks. Such essential equipment will help protect those who continue to produce our agricultural products and contribute so much to our nation’s food security. In the past week, a heat wave has brought extreme temperatures to almost every corner of California. Temperatures reached 107 degrees in Santa Cruz, California, known for its moderate climate, and Death Valley broke records when it reached 130 degrees. Exposure to that type of heat can result in heat-related illnesses, ranging from exhaustion to more serious symptoms like stroke and organ damage. At the same time, excessive heat dries the landscape, making it more susceptible to fire. To date in 2020, 1,034 wildfires have burned 381,000 acres of National Forest System lands in California, and 7,330 wildfires have burned 1.1 million acres across all jurisdictions. Smoke from these wildfires contains chemicals, gasses, and fine particles that also can harm human health. In the state of California, emergency regulations stipulate that, in workplace settings with significant wildfire smoke exposure, when the current Air Quality Index (AQI) for PM2.5 particulate is 151 or greater, employers must provide proper respiratory protection equipment to their employees, including N-95 masks, or equivalent masks that filter out fine particles from the smoke. -

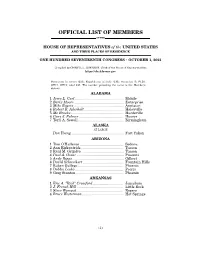

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Union Calendar No. 852 115Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 115–1100

1 Union Calendar No. 852 115th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 115–1100 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES FOR THE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS DECEMBER 21, 2018.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–917 WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:03 Jan 05, 2019 Jkt 033917 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR1100.XXX HR1100 lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS WILLIAM M. ‘‘MAC’’ THORNBERRY, Texas, Chairman WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina ADAM SMITH, Washington JOE WILSON, South Carolina ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey SUSAN A. DAVIS, California ROB BISHOP, Utah JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio RICK LARSEN, Washington MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JIM COOPER, Tennessee BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas JOE COURTNEY, Connecticut DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts ROBERT J. WITTMAN, Virginia JOHN GARAMENDI, California MIKE COFFMAN, Colorado JACKIE SPEIER, California VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri MARC A. VEASEY, Texas AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii MO BROOKS, Alabama BETO O’ROURKE, Texas PAUL COOK, California DONALD NORCROSS, New Jersey BRADLEY BYRNE, Alabama RUBEN GALLEGO, Arizona SAM GRAVES, Missouri SETH MOULTON, Massachusetts ELISE M. STEFANIK, New York COLLEEN HANABUSA, Hawaii MARTHA MCSALLY, Arizona CAROL SHEA–PORTER, New Hampshire STEPHEN KNIGHT, California JACKY ROSEN, Nevada STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma A. DONALD MCEACHIN, Virginia SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee SALUD O.