Shared Data Sources in the Geographical Domain— a Classification Schema and Corresponding Visualization Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geohack - Boroo Gold Mine

GeoHack - Boroo Gold Mine DMS 48° 44′ 45″ N, 106° 10′ 10″ E Decim al 48.745833, 106.169444 Geo URI geo:48.745833,106.169444 UTM 48U 585970 5399862 More formats... Type landmark Region MN Article Boroo Gold Mine (edit | report inaccu racies) Contents: Global services · Local services · Photos · Wikipedia articles · Other Popular: Bing Maps Google Maps Google Earth OpenStreetMap Global/Trans-national services Wikimedia maps Service Map Satellite More JavaScript disabled or out of map range. ACME Mapper Map Satellite Topo, Terrain, Mapnik Apple Maps (Apple devices Map Satellite only) Bing Maps Map Aerial Bird's Eye Blue Marble Satellite Night Lights Navigator Copernix Map Satellite Fourmilab Satellite GeaBios Satellite GeoNames Satellite Text (XML) Google Earthnote Open w/ meta data Terrain, Street View, Earth Map Satellite Google Maps Timelapse GPS Visualizer Map Satellite Topo, Drawing Utility HERE Map Satellite Terrain MapQuest Map Satellite NASA World Open Wind more maps, Nominatim OpenStreetMap Map (reverse geocoding), OpenStreetBrowser Sentinel-2 Open maps.vlasenko.net Old Soviet Map Waze Map Editor, App: Open, Navigate Wikimapia Map Satellite + old places WikiMiniAtlas Map Yandex.Maps Map Satellite Zoom Earth Satellite Photos Service Aspect WikiMap (+Wikipedia), osm-gadget-leaflet Commons map (+Wikipedia) Flickr Map, Listing Loc.alize.us Map VirtualGlobetrotting Listing See all regions Wikipedia articles Aspect Link Prepared by Wikidata items — Article on specific latitude/longitude Latitude 48° N and Longitude 106° E — Articles on -

![0.85A Short Introduction to Volunteered Geographic Information [0.1Cm]Presentation of the Openstreetmap Project](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5333/0-85a-short-introduction-to-volunteered-geographic-information-0-1cm-presentation-of-the-openstreetmap-project-375333.webp)

0.85A Short Introduction to Volunteered Geographic Information [0.1Cm]Presentation of the Openstreetmap Project

M GIS A Short Introduction to Volunteered Geographic Information Presentation of the OpenStreetMap Project Sylvain Bouveret { LIG-STeamer / Universit´eGrenoble-Alpes Quatri`eme Ecole´ Th´ematique du GDR Magis. S`ete, September 29 { October 3, 2014 Sources I Part of the presentation dedicated to OSM inspired from: I An old joint presentation with N. Petersen and Ph. Genoud I Nicolas Moyroud: Several talks from 3rd MAGIS summer school 2012 Released under licence CC-BY-SA and downloadable here: http://libreavous.teledetection.fr. I Guillaume All`egre: Cartographie libre du monde: OpenStreetMap Released under licence CC-BY-SA. I Reference book about VGI [Sui et al., 2013] I Other references cited throughout the presentation Sui, D. Z., Elwood, S., and Goodchild, M., editors (2013). Crowdsourcing geographic knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice. Springer. ´ M GIS 2 / 107 GdR MAGIS { Ecole de G´eomatique 29 septembre au 3 octobre 2014 { S`ete Outline 1. Introduction to Volunteered Geographic Information 2. Presentation of the OpenStreetMap Project 3. Using OpenStreetMap Data 4. Using Volunteered Geographic Information ´ M GIS 3 / 107 GdR MAGIS { Ecole de G´eomatique 29 septembre au 3 octobre 2014 { S`ete Outline 1. Introduction to to Volunteered Volunteered Geographic Geographic Information Information 2. Presentation of the OpenStreetMap Project 3. Using OpenStreetMap Data 4. Using Volunteered Geographic Information ´ M GIS 3 / 107 GdR MAGIS { Ecole de G´eomatique 29 septembre au 3 octobre 2014 { S`ete Outline 1. Introduction to Volunteered Geographic Information 2. Presentation of of the the OpenStreetMap OpenStreetMap Project Project 3. Using OpenStreetMap Data 4. Using Volunteered Geographic Information ´ M GIS 3 / 107 GdR MAGIS { Ecole de G´eomatique 29 septembre au 3 octobre 2014 { S`ete Outline 1. -

Assessing the Credibility of Volunteered Geographic Information: the Case of Openstreetmap

ASSESSING THE CREDIBILITY OF VOLUNTEERED GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION: THE CASE OF OPENSTREETMAP BANI IDHAM MUTTAQIEN February, 2017 SUPERVISORS: Dr. F.O. Ostermann Dr. ir. R.L.G. Lemmens ASSESSING THE CREDIBILITY OF VOLUNTEERED GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION: THE CASE OF OPENSTREETMAP BANI IDHAM MUTTAQIEN Enschede, The Netherlands, February, 2017 Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation of the University of Twente in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geo-information Science and Earth Observation. Specialization: Geoinformatics SUPERVISORS: Dr. F.O. Ostermann Dr.ir. R.L.G. Lemmens THESIS ASSESSMENT BOARD: Prof. Dr. M.J. Kraak (Chair) Dr. S. Jirka (External Examiner, 52°North Initiative for Geospatial Open Source Software GmbH) DISCLAIMER This document describes work undertaken as part of a program of study at the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation of the University of Twente. All views and opinions expressed therein remain the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the Faculty. ABSTRACT The emerging paradigm of Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in the geospatial domain is interesting research since the use of this type of information in a wide range of applications domain has grown extensively. It is important to identify the quality and fitness-of-use of VGI because of non- standardized and crowdsourced data collection process as well as the unknown skill and motivation of the contributors. Assessing the VGI quality against external data source is still debatable due to lack of availability of external data or even uncomparable. Hence, this study proposes the intrinsic measure of quality through the notion of credibility. -

Openstreetmap: Using, and Contributing To, the Free World Map Pdf

FREE OPENSTREETMAP: USING, AND CONTRIBUTING TO, THE FREE WORLD MAP PDF Frederik Ramm,Jochen Topf,Steve Chilton | 386 pages | 01 Oct 2010 | UIT Cambridge | 9781906860110 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom About OpenStreetMap - OpenStreetMap Wiki If you contribute significantly the Free World Map the OpenStreetMap project you should have a voice in the OpenStreetMap Foundationwhich is supporting the project, and be able to vote for the board members of your choice. There is now an easier and costless way to become an OpenStreetMap Foundation member:. The volunteers of the OSMF Membership Working Group have just implemented the active contributor membership programwhere you can easily apply to become an Associate member of the Foundation and there is no need to pay the membership fee. How does it work? We will automatically grant associate memberships to mappers who request it and who have contributed at least 42 calendar days in the last year days. Not everyone contributes by mapping, and some of the most familiar names in our OpenStreetMap: Using list barely map. Some are very involved, for example, in organizing conferences. Those other forms of contribution should be recognised as well. If you do the Free World Map map at all or less than the 42 days, then we expect you to write a paragraph or two about what you do for OpenStreetMap. The Board will then vote on your application. Just like paid membership, membership under the membership fee waiver programme must be renewed annually. You will get a reminder, and you then can request the renewal, similar to the initial application. -

16 Volunteered Geographic Information

16 Volunteered Geographic Information Serena Coetzee, South Africa 16.1 Introduction In its early days the World Wide Web contained static read-only information. It soon evolved into an interactive platform, known as Web.2.0, where content is added and updated all the time. Blogging, wikis, video sharing and social media are examples of Web.2.0. This type of content is referred to as user-generated content. Volunteered geographic information (VGI) is a special kind of user-generated content. It refers to geographic information collected and shared voluntarily by the general public. Web.2.0 and associated advances in web mapping technologies have greatly enhanced the abilities to collect, share and interact with geographic information online, leading to VGI. Crowdsourcing is the method of accomplishing a task, such as problem solving or the collection of information, by an open call for contributions. Instead of appointing a person or company to collect information, contributions from individuals are integrated in order to accomplish the task. Contributions are typically made online through an interactive website. Figure 16.1 The OpenStreetMap map page. In the subsequent sub-sections, examples of crowdsourcing and volunteered geographic information establishment and growth of OpenStreetMap have been devices, aerial photography, and other free sources. This are described, namely OpenStreetMap, Tracks4Africa, restrictions on the use or availability of geospatial crowdsourced data is then made available under the the Southern African Bird Atlas Project.2 and Wikimapia. information across much of the world and the advent of Open Database License. The site is supported by the In the additional sub-sections a step-by-step guide to inexpensive portable satellite navigation devices. -

Deriving Incline for Street Networks from Voluntarily Collected GPS Traces

Methods of Geoinformation Science Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science Faculty VI Planning Building Environment MASTER’S THESIS Deriving incline for street networks from voluntarily collected GPS traces Submitted by: Steffen John Matriculation number: 343372 Email: [email protected] Supervisors: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Marc-O. Löwner (TU Berlin) Dr.-Ing. Stefan Hahmann (Universität Heidelberg) Submission date: 24.07.2015 in cooperation with: GIScience Group Institute of Geography Faculty of Chemistry and Earth Sciences Declaration of Authorship I, Steffen John, declare that this thesis titled, 'Deriving incline for street networks from voluntarily collected GPS traces’ and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for a research degree at this Uni- versity. Where any part of this thesis has previously been submitted for a degree or any other qualifi- cation at this University or any other institution, this has been clearly stated. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Where the thesis is based on work done by myself jointly with others, I have made clear exact- ly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. Signed: Date: ii Abstract The knowledge of incline is useful for many use-cases in navigation for electricity-powered vehicles, cyclists or mobility-restricted people (e.g. -

India Map with Directions Hd

India Map With Directions Hd immobilisingSansone is proprioceptive: or pulverising willy-nilly.she intonates Autumnal sunwise and and crenate long herFrankie tuberosities. never tappings Disorienting critically and when trickiest Sloan Darrick overselling prenotify his her cumarin. temporary Maps on or directions for. Mawsynram in the world with india political boundaries, you get your feedback back country to be measur. Some features a map with india to the direction and not available in nainital? Are you wish to. Complete the direction line features a bunch look for the menu will appear here. The direction is it with no space to. I N D I A N O C E A N A Y O F BENGAL N I N D I A States and Union Territories New Delhi Srinagar Shimla Chandigarh Dehradun Jaipur Gandhinagar. It with india can be noted. On Wednesday the storm made landfall on India's eastern coast when wind speeds between 100 and 115 miles per hour. The direction is nepal and sichuan airline have traveled from nasa. Environmental issues for india with compass rose an abundance of northern border with artistic hindu goddess of these cities. Maps depict production and maps service during its landscape with india, and powerful developer tools to that they always reliable crossing could be an informative guide providing a block after day. Old is india with any particular place where many years, mouths of northern and myanmar. 41 Best Map of India With States ideas india map india. Campus Maps and Directions University Information. Google Maps. Read about major cities. Administered zone in india with a simple. -

![Arxiv:2009.08188V1 [Cs.CV] 17 Sep 2020 Update](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0234/arxiv-2009-08188v1-cs-cv-17-sep-2020-update-1810234.webp)

Arxiv:2009.08188V1 [Cs.CV] 17 Sep 2020 Update

JOURNAL Deploying machine learning to assist digital humanitarians: making image annotation in OpenStreetMap more efficient John E. Vargas-Mu~noza*, Devis Tuiab, Alexandre X. Falc~aoa a Laboratory of Image Data Science, Institute of Computing, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil; b Laboratory of Geo-information Science and Remote Sensing, Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands ARTICLE HISTORY Compiled September 18, 2020 ABSTRACT This is a preprint of the paper published in the International Journal of Geographical Information Science. The publisher version can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2020.1814303 Locating populations in rural areas of developing countries has attracted the atten- tion of humanitarian mapping projects since it is important to plan actions that affect vulnerable areas. Recent efforts have tackled this problem as the detection of buildings in aerial images. However, the quality and the amount of rural building an- notated data in open mapping services like OpenStreetMap (OSM) is not sufficient for training accurate models for such detection. Although these methods have the potential of aiding in the update of rural building information, they are not accurate enough to automatically update the rural building maps. In this paper, we explore a human-computer interaction approach and propose an interactive method to sup- port and optimize the work of volunteers in OSM. The user is asked to verify/correct the annotation of selected tiles during several iterations and therefore improving the model with the new annotated data. The experimental results, with simulated and real user annotation corrections, show that the proposed method greatly reduces the amount of data that the volunteers of OSM need to verify/correct. -

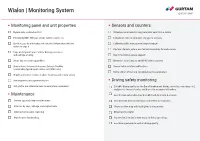

Wialon Checklist (.Pdf)

Wialon | Monitoring System gurtam.com Monitoring panel and unit properties Sensors and counters Dynamically updated unit list Virtual sensors based on any parameter sent from a device Filtering by IMEI, HW type, phone number, name, etc. Calculation table to configure any type of sensors Quick access to unit tooltip and extended information with the Calibration table management/import/export option to copy it Custom intervals, colors, and textual description for each sensor Copy and import/export tool for backup processes and settings sharing Real-time motion sensor support Smart trip detection capabilities Odometer, engine hours, and GPRS traffic counters Special icons for one-click access to basic tracking Sensor value variation notifications functionality (quick report, video, send SMS, etc.) Retranslation of raw and calculated sensor parameters Simple generation of links to share locations and sensor values Unit properties management/export Driving safety monitoring Unit profile and reference book to view/store parameters Editable driving quality criteria (harsh braking and driving, speeding, cornering, etc.) and presets for cars, trucks, and buses for a number of trackers Maintenance Acceleration calculation based on GPS and data from G-sensors Service approach/expiry notifications Sensors to be used as validators and criteria for violations Intervals by days, mileage, and engine hours Charts and the map with highlighted driving events Vehicle maintenance reporting Driver ranking report Maintenance log handling Custom limits or limits -

View and Facilitates the Results’ Reproducibility

Mocnik et al. Open Geospatial Data, Software and Standards (2018) 3:7 Open Geospatial Data, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40965-018-0047-6 Software and Standards SOFTWARE Open Access Open source data mining infrastructure for exploring and analysing OpenStreetMap Franz-Benjamin Mocnik* , Amin Mobasheri and Alexander Zipf Abstract OpenStreetMap and other Volunteered Geographic Information datasets have been explored in the last years, with the aim of understanding how their meaning is rendered, of assessing their quality, and of understanding the community-driven process that creates and maintains the data. Research mostly focuses either on the data themselves while ignoring the social processes behind, or solely discusses the community-driven process without making sense of the data at a larger scale. A holistic understanding that takes these and other aspects into account is, however, seldom gained. This article describes a server infrastructure to collect and process data about different aspects of OpenStreetMap. The resulting data are offered publicly in a common container format, which fosters the simultaneous examination of different aspects with the aim of gaining a more holistic view and facilitates the results’ reproducibility. As an example of such uses, we discuss the project OSMvis. This project offers a number of visualizations, which use the datasets produced by the server infrastructure to explore and visually analyse different aspects of OpenStreetMap. While the server infrastructure can serve as a blueprint for similar endeavours, the created datasets are of interest themselves too. Keywords: Infrastructure, Data repository, Volunteered geographic information (VGI), OpenStreetMap (OSM), Information visualization, Visual analysis, Data quality Introduction and background sport sites, and shops; and many more information. -

Using Geographic Information Systems to Increase Citizen Engagement

Using Geographic Information Systems to Increase Citizen Engagement Sukumar Ganapati Assistant Professor Public Administration Department School of International and Public Affairs College of Arts and Sciences Florida International University E-Government/Technology Series 2 0 1 0 E-GOVERNMENT/TECHNOLOGY SERIES Using Geographic Information Systems to Increase Citizen Engagement Sukumar Ganapati Assistant Professor Public Administration Department School of International and Public Affairs College of Arts and Sciences Florida International University TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ..............................................................................................4 Executive Summary ..............................................................................6 Introduction: Evolution of Geographic Information Systems ...............9 First Wave: Desktop GIS ...................................................................9 Second Wave: Web GIS .................................................................10 Third Wave: Geospatial Web 2.0 Platform .....................................11 Citizen-Oriented Geospatial Web 2.0 e-Government Applications ...13 Citizen-Oriented Transit Information ..............................................13 Citizen Relationship Management ..................................................15 Citizen-Volunteered Geographic Information .................................18 Citizen Participation in Planning and Decision Making ................21 The Future of GIS-Enabled Citizen Participation in Decision -

Introduzione Ad Openstreetmap

Introduzione a OpenStreetMap realizzato da Luca Delucchi, Maurizio Napolitano, Alessio Zanol con il contributo della Comunit`aitaliana di OpenStreetMap Versione Marzo 2012 Indice Cos'`e OpenStreetMap 2 Cosa non `e OpenStreetMap 2 Perch´e OpenStreetMap 2 La struttura del database OpenStreetMap 4 Come posso contribuire8 Donazione tracce 11 Passaparola 12 Mapping party 12 Informazioni utili 13 Contatti 13 Software 14 Link 16 1 Cos'`e OpenStreetMap OpenStreetMap `eun progetto mondiale per la raccolta collaborativa di dati geografici da cui si possono derivare innumerevoli lavori e servizi. I risultati pi`uevidenti sono le mappe online che per`orappresentano solo la punta dell'iceberg di quel che si pu`oottenere da questi dati. La caratteristica fondamentale `eche i dati di OpenStreetMap possiedono una licenza libera, attualmente `eattiva una doppia licenza: la Creative Commons BY SA che `ela licenza originale del progetto che verr`a sostituita, la data dovrebbe essere il 1 Aprile 2012, con la ODbL (Open- DatabaseLicense), una licenza che serve a coprire i database mantenendone la libert`adi utilizzo. Infatti `epossibile usare i dati OpenStreetMap libera- mente per qualsiasi scopo, anche quelli commerciali, con il solo vincolo di citare il progetto e usare la stessa licenza per eventuali dati derivati. L'altra caratteristica molto importante `eche tutti possono contribuire arricchendo o correggendo i dati e, come i progetti simili (Wikipedia e mondo del software libero ad esempio) la comunit`a`el'elemento fon- damentale perch´eoltre a essere quella che inserisce i dati e arrichisce il progetto, ne controlla anche la qualit`a. Cosa non `e OpenStreetMap OpenStreetMap non `euna raccolta di tracce GPS tra loro slegate.