Text, Cases Commentary Hong Kong Legal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sentencing Conference Held by DOJ *********************************

Sentencing conference held by DOJ ********************************* The Prosecutions Division of the Department of Justice today (January 15) held the Sentencing Conference 2012, which was attended by more than 80 participants, including members of the judiciary, prosecutors, criminal law practitioners and scholars. Entitled "A New Sentencing Regime for Hong Kong?", the conference was the first of its kind organised by the Department of Justice to stimulate discussion on the pros and cons of establishing a sentencing council in Hong Kong and reflect upon the existing sentencing regime with reference to the experience of the Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council. In delivering the welcoming address, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Mr Kevin Zervos, SC, said: "In the pursuit of upholding the rule of law and in serving the interests of justice and the community, a prosecutor must always act fairly and properly. The fundamental task of a prosecutor is to be a minister of justice." He also emphasised the need to protect the public bearing in mind the important public dimension of sentencing and the need to maintain public confidence and support in our criminal justice system. The keynote speaker at the conference was the Dean of Law at the University of Monash, Professor Arie Freiberg, a leading expert on sentencing law in Australia. He is also the Chairman of the Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council. After giving a presentation on the experience of the Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Professor Freiberg, together with Mr Clive Grossman, SC, Dr Gerard McCoy, SC, Mr Keith Yeung, SC, Mr Stephen Hung and Professor Simon Young, participated in the panel discussion with Mr Zervos, SC, as the moderator. -

Sopa-Scoopzhoutarget

Friday, August 30, 2013 A3 Beam me up LEADING THE NEWS K-pop stars are embracing hologram COMMERCE Oil giants technology to reach a wider audience > L I F E C 7 banned Unwelcome guest Create your dream home Health headache from new Aquino cancels visit to China: Chic, stylish furniture Migraines can cause INVESTMENT TEAMS TO BE REINED IN Beijing says he was never and accessories for permanent brain damage projects invited in the first place discerning buyers and raise risk of strokes Commerce Ministry targets extravagance by delegations sent Foreign direct investment is a Previously, investment jun- key economic indicator used to kets were believed to be immune > LEA D ING T HE N EWS A 3 > 20-PAG E SPE CIA L REP O R T > WORLD A15 to Hong Kong and Macau to seek investment for their regions gauge officials’ performance, and from the campaign against offi- Beijing makes state ................................................ dozens of delegations from local cial extravagance. overstated the number of partici- His remarks followed the flag- governments flock to Hong Kong The The People’s Daily said busi- energy companies pay Daniel Ren pants and the value of deals ship newspaper’s harsh criticism every year to seek such invest- ness delegations stayed in five- [email protected] phenomenon the price for failing to signed during their promotional on Monday of investment dele- ments. star hotels and invited business- activities. gations travelling to Hong Kong. Yao admitted that the delega- reflects a severe men to expensive restaurants, meet pollution targets The Ministry of Commerce has “They were desperate to get This was the first time that a tions played a positive role in level of spending as much as 1,000 yuan pledged to rein in extravagance abig number of foreign business- Communist Party mouthpiece spurring the nation’s economic (HK$1,260) per head for a break- ............................................... -

Hong Kong Bar Association Circular No

Hong Kong Bar Association Circular No. 245/19 To : All Members & Mess Members of the Bar Association From : Jonathan Chang – Honorary Secretary Date : 3 December 2019 PRACTICE NOTE : NEW PRACTICE WHERE FLAGRANT INCOMPETENCE IS ADVANCED AS A GROUND OF APPEAL Members’ attention is drawn to the Court of Appeal judgment in HKSAR v Apelete [2019] HKCA 1189 whereby a new practice is imposed by the Court where flagrant incompetence of legal representative(s) at trial is advanced as a ground of appeal: 1. An appellate counsel has a duty to satisfy himself that the ground is properly arguable, i.e. there is a palpably sound basis for such allegations to be made, failing which such allegations must never be advanced: see also HKSAR v Li Xiaoxiang (2018) 21 HKCFAR 272 at [31]. 2. In making that assessment, the appellate counsel must look for independent and objective evidence to support the complaint and, save where there are good and compelling reasons not to do so, make full and proper enquiries of the previous legal representatives at trial in relation to the complaint before articulating it as a ground of appeal. The appellate counsel must then add an appropriate certificate in the grounds of appeal that he has complied with this duty when relying on such a ground. 3. Further, a signed waiver of LPP from the applicant in respect of the trial legal representatives and an affirmation in support of the complaint must be filed at the same time as the ground of appeal. 4. If subsequent material comes to light casting doubt on the applicant’s claims, there is a continuing duty on the appellate counsel to evaluate the propriety of the grounds of the complaint. -

Secretary for Justice Speaks About Appointment of DPP *****************************************************

Secretary for Justice speaks about appointment of DPP ***************************************************** Following is the transcript of remarks by the Secretary for Justice, Mr Rimsky Yuen, SC, and the Director of Public Prosecutions (Designate), Mr Keith Yeung, SC, to the media today (August 1): Secretary for Justice: Dear friends from the media, the purpose of today's meeting is to announce the Government's appointment of Mr Keith Yeung Kar-hung, SC, to succeed Mr Kevin Zervos, SC, as the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), who will leave the civil service in September. A prosecution service that is fair, just, in accordance with the law and free from political intervention is of fundamental importance in maintaining the rule of law. The Department of Justice (DoJ) has all along placed great emphasis on the quality of our prosecution work. In November 2012, the DoJ conducted a promotion-cum-open recruitment exercise so as to source a suitable candidate for the post of DPP. After the selection process which took more than six months, the Selection Committee chaired by the Secretary for the Civil Service considered Mr Yeung to be the most suitable candidate and decided to appoint him as the next DPP. With over 25 years of experience in the legal profession, Mr Yeung has a wealth of experience and an in-depth knowledge in criminal law and civil law, especially commercial crime and securities-related legal matters. Over the years, Mr Yeung has been actively involved in legal and related services. As the Vice-chairman of the Bar Association as well as in other capacities, he has been involved in different areas of work for promoting the development of legal services and the legal profession. -

Restricting the Use of the Death Penalty: the Relevance of International Human Rights Norms to Capital Punishment in Asia

International Conference on Capital Punishment in Asia: Progress and Prospects for Law Reform 4-5 November 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME, ABSTRACT OF PAPERS AND BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF SPEAKERS 1 FINAL PROGRAMME Thursday, 3 November 2011 7:00pm- 8:30pm – Welcome Dinner hosted by the City University Law School at Royal Park Hotel, Shatin (by invitation) Friday, 4 November 2011 9:00am-9:30am – Registration, Connie Fan Multi-media Conference room (MMR), CityU 9:30am-11:00am – INAUGURAL SESSION Welcoming Remarks: Professor Anton Cooray, Associate Dean, School of Law, City University of Hong Kong Inaugural Speech: Professor Arthur Ellis, Provost, City University of Hong Kong Opening Address by the Guest of Honour, Mr Kevin P Zervos, Director of Public Prosecutions, Justice Department, Government of the HKSAR Keynote Address: Professor Franklin Zimring, William G Simon Professor of Law, Berkeley Law School – “Large Issues and Small Steps towards Progress in Ending Executions in Asia” Questions/Comments Vote of Thanks: Dr Surya Deva, Associate Professor, School of Law, City University of Hong Kong Group Photo 11:00am-11:15am – Tea (MMR) 11:15am-12:45pm – SESSION I: Death Penalty – Situating Asia within International Human Rights Perspectives Chair: Dr Mark Kielsgard, Assistant Professor, School of Law, City University of Hong Kong 1) Dr Saul Lehrfreund, Executive Director, The Death Penalty Project, London Restricting the Use of the Death Penalty: The Relevance of International Human Rights Norms to Capital Punishment in Asia 2 2) Mr Y S R Murthy, -

Prosecutions Hong Kong 2015

特稿 Feature Articles 黄惠沖資深大律師專訪 Interview with Wesley Wong SC 沈仲平博士專訪 Interview with Dr Alain Sham 黃惠沖資深大律師專訪 Interview with Wesley Wong SC 2015 年 9 月 3 日,黃惠沖資深大律師出任法律政策專員,掌管法律政策科。他是首批由 本司培訓的見習律政人員,在 1994 年 8 月 2 日成為檢察官時被選派至刑事檢控科工作, 其後他也在司內其他科別服務。黃先生在 2011 年出任副刑事檢控專員,並由 2012 年 8 月 2 日起擔任刑事檢控專員辦公室人事主管,此時距離他首次加入刑事檢控科剛好 18 年。 這位律政專員談及過往的工作和經驗如何造就他,讓他有今日的信心履行現時範圍如此廣 泛的職責。 Mr Wesley Wong Wai-chung SC assumed the post of Solicitor General on 3 September 2015 to head the Legal Policy Division. From the Department’s first crop of home-grown Legal Trainees, he was first posted to the Prosecutions Division on 2 August 1994, and thereafter served elsewhere in the Department. He had been a Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions since 2011 and started discharging the role of Chief of Staff of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions from 2 August 2012, exactly 18 years after he first joined the Division. The Solicitor General talks about how his previous work and experience has benefited and allowed him to discharge his present role with such a broad span of responsibility with the confidence which he otherwise would not be able to command. 由見習律政人員 ( 大律師 ) 到法律政策專員, From Legal Trainee (Barrister) to Solicitor General, Mr Wesley Wong SC’s 黃先生過去 22 年經歷的升遷之路,都甚具啓 acceleration through the ranks in the past 22 years is nothing short of 發意義。他曾三度 (1994 至 1996 年、1998 至 inspiring. Having had three spells (1994 to 1996, 1998 to 1999 and 1999 年和 2010 至 2015 年 ) 在本科工作。本司 2010 to 2015) in the Division, he is the only other former prosecutor 歷來曾任職檢控官而獲委任為法律政策專員者, (apart from the Honourable Mr Justice Stock GBS1 and retired High Court 除了司徒敬法官 1 和高等法院榮休法官杜輝 2 外, Judge Mr Justice Duffy2) in this Department’s history to be appointed 就只有黃先生一人了。 Solicitor General. -

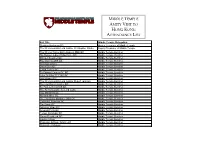

Middle Temple Amity Visit to Hong Kong Attendance List

MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO HONG KONG ATTENDANCE LIST Full Title Middle Temple Delegation Stephen Hockman QC Master Treasurer of Middle Temple The Rt Honourable Lord Justice Christopher Clarke Deputy Treasurer of Middle Temple The Rt Hon Dame Elish Angiolini DBE QC Middle Temple Bencher His Honour Judge Phillip Bartle QC Middle Temple Bencher Michael Bowsher QC Middle Temple Bencher Paul Darling OBE QC Middle Temple Bencher Sheilagh Davies Middle Temple Bencher David Elvin QC Middle Temple Bencher Judith Farbey QC Middle Temple Bencher Sir Edward Garnier QC MP Middle Temple Bencher John Griffiths SC CMG QC Middle Temple Bencher Ann Hussey QC Middle Temple Bencher The Rt Honourable Lord Justice Rupert Jackson Middle Temple Bencher The Hon Daniel Janner QC Middle Temple Bencher Sir Paul Jenkins KCB QC Middle Temple Bencher The Rt Honourable the Lord Judge Middle Temple Bencher Guy Mansfield QC Middle Temple Bencher Richard Miller QC Middle Temple Bencher The Hon Barry Mortimer GBS QC Middle Temple Bencher Catherine Newman QC Middle Temple Bencher Tim Owen QC Middle Temple Bencher Adrienne Page QC Middle Temple Bencher Amanda Pinto QC Middle Temple Bencher Fergus Randolph QC Middle Temple Bencher Simon Readhead QC Middle Temple Bencher Alastair Sharp Middle Temple Bencher Professor Anthony Smith LLD Middle Temple Bencher Christiane Valansot Middle Temple Bencher Derek Wood CBE QC Middle Temple Bencher Brigadier Charles Wright Middle Temple Bencher Alan Bates Middle Templar Tim Becker Middle Templar Laura Feldman Middle Templar Juliette -

ICAC Committee's Independence, Competence Should Be Respected

8 | Thursday, December 27, 2018 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY COMMENT HK Editor’s note: China Daily Hong Kong Edition has launched a photo-sharing campaign on Instagram. You can share your photos by tagging #hk24hr, and ICAC committee’s independence, we’ll choose the best ones to publish in the newspaper. Birds at dawn competence should be respected Tony Kwok argues Hong Kong should have full confidence in anti-corruption watchdog’s advice on former chief executive’s case, and that it’s time to end briefing out prosecution cases n recent years, the Hong Kong Bar and a well-known public fi gure. There are also Association has lost much of its pub- two expatriate members — Hans Michael Jeb- lic credibility by, seemingly, taking a sen and Nicholas Robert Sallnow-Smith — both habitual anti-government and anti- very prominent businessmen in Hong Kong. China stance on many controversial Are these people likely to be rubber-stamping issues. The latest such example is its the SJ’s decision, as alleged by opposition law- relentless criticism of the joint check- maker Lam Cheuk-ting? point (co-location) arrangement at the West Tony Kwok Lam’s recent comment that the ORC always IKowloon Terminus of the Hong Kong Section of The author was the fi rst Chinese deputy com- endorses the justice chief’s legal opinion is the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express missioner and head of operations of the ICAC really a big insult to them! Lam was so junior Rail Link despite the facility’s substantial and, currently, an adjunct professor of HKU while working for the ICAC that he never had Space and an international anti-corruption advantage of convenience to the public. -

Doj2010e.Pdf

2010 2010 04 Foreword by the Secretary for Justice 07 Highlights of 2008 and 2009 21 An overview of the Department of Justice 25 Civil Division 35 International Law Division 43 Law Drafting Division 51 Legal Policy Division 59 Prosecutions Division 69 Administration & Development Division 75 The department's links with other jurisdictions 79 Statistics Foreword by the Secretary for Justice his is the seventh periodical review of the Twork of the Department of Justice. It is the third since I took office as Secretary for Justice in October 2005 and covers the period from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2009. As with previous editions, this review reflects the wide range of the department’s work. It is fair to say that there are few areas within the broad sweep of government activity which have not required legal input from my department’s counsel at one time or another. 2007, the department introduced a Bill to the I spoke in my foreword to the 2008 review of Legislative Council in July 2009 which proposes to anticipated developments in a number of areas, reform arbitration law in Hong Kong by creating including mediation, arbitration and reciprocal a single and more user-friendly regime for all enforcement of judgments with the Mainland. I types of arbitration, based on the Model Law on am pleased to say that the last two years have seen International Commercial Arbitration of the United significant progress in each of these. Nations Commission on International Trade Law. The department worked closely with arbitration On mediation, the cross-sector Working Group practitioners in Hong Kong in formulating the I established and chaired held its first meeting proposals embodied in the Bill. -

Speech by SJ at Criminal Law Conference 2012 (English Only) *********************************************************

Speech by SJ at Criminal Law Conference 2012 (English only) ********************************************************* Following is the opening address by the Secretary for Justice, Mr Rimsky Yuen, SC, at the Criminal Law Conference 2012 today (November 17): Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen: It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the Criminal Law Conference 2012, organised by the Prosecutions Division of the Department of Justice. The rule of law and judicial independence are the core values of Hong Kong. Under the Basic Law, Hong Kong remains a common law jurisdiction, and enjoys independent judicial power including that of final adjudication. Rights and freedoms of Hong Kong residents and other individuals are safeguarded under the Basic Law, the Bill of Rights Ordinance and other relevant legislations. As far as criminal justice is concerned, it has always been our aim to put in place a system that is fair and effective, and one that strikes the right balance between the protection of human rights and the need to protect the community from criminal activities. The annual surveys conducted by the Political and Economic Risk Consultancy on expatriates' confidence in different judicial systems around the world regularly put Hong Kong's legal system in a very favourable light. Its latest report released in August this year described our system as "transparent, accessible and efficient". Indeed, our robust legal system has been one of the most important factors contributing to the continued success of Hong Kong. It has enabled our city to remain vibrant and cosmopolitan, and to win the reputation of being one of the world's freest and competitive economy, commanding the confidence of both the local and international communities. -

The Judicial Construction of Hong Kong's Basic

The Judicial Construction of Hong Kong’s Basic Law: Courts, Politics and Society after 1997 Lo Pui Yin Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2014 ISBN 978-988-8208-07-4 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements xi Abbreviations xiii Table of Cases xv Table of Legislation xxxv Part 1: Introduction and Background to the Study Chapter 1 Concerns and Organization 3 Chapter 2 The Multifaceted Basic Law and Its Assumed Purpose 15 Chapter 3 The Background of Concepts 19 3.1 One Country, Two Systems 19 3.2 High Degree of Autonomy 28 3.3 Executive-Led Government 35 3.4 Separation of Powers 51 3.5 Independent Judicial Power and Judicial Review 60 Part 2: The Pioneering Judicial Voyage: 1997–2013 Chapter 4 1997–1998: Introspective Institutional Clarifi cation 69 Chapter 5 1999: The Triumph, Tragedy and Restarting of Constitutional Assertiveness 73 Chapter 6 2000–2001: Demonstrating the Common Law Approach 83 Chapter 7 2002–2003 91 7.1 Mopping up Right of Abode Cases and Delimiting Constitutional -

Retrospective and Prospective Overruling Professor Johannes

Disturbing the Past and Jeopardising the Future: Retrospective and Prospective Overruling Professor Johannes Chan Dean, Faculty of Law The University of Hong Kong ___________________ Unlike legislation, judicial judgments normally have retrospective and prospective effect. By necessity, every judicial decision is dealing with events that have taken place in the past, and the court is trying to apply the law as it has found to be at the time when those events took place. At the same time, judges do not create law. They declare what the law has always been and will be, at least insofar as the declaratory theory of law is accepted. Hence, the judgment represents the law as it always is, and the law that will continue to apply to the future, a consequence that is fostered by the doctrine of precedents. These principles work well in the normal circumstances, but what if a declaration of illegality of a Government act or unconstitutionality of a statutory provision would have drastic consequences for the community? Such drastic consequences may take the form of disturbing or even reversing a long line of previous judicial or administrative decisions, or resulting in a legal vacuum such that it would be very difficult or even impossible for the Government or law enforcement agencies to continue to operate satisfactorily. This gives rise to the controversial issue of how far the courts can limit the temporal effect of its judgments so as to avoid disturbing past decisions or creating a legal vacuum in the future before necessary remedial measures can be taken.1 On the one hand, a fundamental aspect of 1 This article was partly based on a previous article that has appeared as Johannes Chan, ‘Some Reflections on Remedies in Administrative Law’ (2009) 39 HKLJ 321-337.