Electoral Law Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of an Investigation in Respect Of

Report of an investigation in respect of - Vote Leave Limited - Mr Darren Grimes - BeLeave - Veterans for Britain Concerning campaign funding and spending for the 2016 referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU 17 July 2018 1 Other formats For information on obtaining this publication in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Electoral Commission. Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The Electoral Commission is the independent body which oversees elections and regulates political finance in the UK. We work to promote public confidence in the democratic process and ensure its integrity. 2 Contents 1 Introduction..................................................................................................... 4 2 The decision to investigate ............................................................................. 9 3 The investigation .......................................................................................... 12 4 The investigation findings ............................................................................. 16 Joint spending by Vote Leave and BeLeave ................................................... 16 Vote Leave’s spending limit ............................................................................. 21 Other issues with Vote Leave’s spending return ............................................. 24 BeLeave’s spending ........................................................................................ 25 Mr Grimes’ spending return ............................................................................ -

Post Layout 1

Friday 15 International Friday, July 26, 2019 Britain new leader rejects ‘unacceptable’ Brexit deal Johnson urged EU leaders to rethink their opposition LONDON: Britain’s new Prime Minister Boris ing the EU after 46 years without an agreement will Johnson yesterday called the current Brexit deal be less painful than economists warn. The markets negotiated with the EU “unacceptable” and set were relieved by the appointment of former preparations for leaving the bloc without an agree- Deutsche Bank Sajid Javid as finance chief. The ment as a “top priority” for the government. In a pound held steady against the dollar and euro as pugnacious debut in parliament, the former London traders waited for Johnson’s first policy moves. mayor urged EU leaders to rethink their opposition Other appointments were more divisive. Brexit to renegotiating the deal. hardliner Dominic Raab became foreign secretary After installing a right-wing government follow- and Jacob Rees-Mogg - leader of a right-wing ing a radical overhaul, Johnson doubled down on faction of Conservatives who helped bring about his promise to lead Britain out of the EU by Octo- May’s demise - as the government’s parliament ber 31 at any cost. In case of a no-deal exit, he also representative. New interior minister Priti Patel threatened to withhold the £39 billion ($49 billion) has previously expressed support for the death divorce bill that Britain has previously said it owes penalty and voted against same-sex marriage. The the EU and instead spend the money for prepara- Labor opposition-backing Mirror newspaper tions for leaving with no agreement. -

Disinformation and 'Fake News': Interim Report

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Interim Report Fifth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 24 July 2018 HC 363 Published on 29 July 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) (Chair) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Julian Knight MP (Conservative, Solihull) Ian C. Lucas MP (Labour, Wrexham) Brendan O’Hara MP (Scottish National Party, Argyll and Bute) Rebecca Pow MP (Conservative, Taunton Deane) Jo Stevens MP (Labour, Cardiff Central) Giles Watling MP (Conservative, Clacton) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the inquiry Christian Matheson MP (Labour, City of Chester) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/dcmscom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. -

IN the COUNTY COURT at CENTRAL LONDON Claim No. E40CL216 in the MATTER of the POLITICAL PARTIES, ELECTIONS and REFERENDUMS ACT 2

IN THE COUNTY COURT AT CENTRAL LONDON Claim No. E40CL216 IN THE MATTER OF THE POLITICAL PARTIES, ELECTIONS AND REFERENDUMS ACT 2000; AND THE POLITICAL PARTIES, ELECTIONS AND REFERENDUMS (CIVIL SANCTIONS) ORDER 2010 BEFORE HHJ DIGHT CBE B E T W E E N: DARREN GRIMES Appellant -and- THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION Respondent _____________________________ NOTICE OF RESPONSE _____________________________ INTRODUCTION 1. The Commission is the independent body which oversees elections and regulates political finance in the UK. It is a body corporate established by statute which consists of nine or ten members, known as Electoral Commissioners and appointed by the Queen, who also appoints one of the Commissioners to be the chairman of the Commission: see ss.1(1)-(5) PPERA. Mr Grimes is an individual who registered as a permitted participant in the 2016 EU referendum. 2. This appeal concerns the decision contained in the Commission’s Statutory Notice dated 16 July 2018 and issued on 17 July 2018 (“the Notice”). In the Notice, the Commission concluded that Mr Grimes had committed offences in connection with four payments made in June 2016 to a Canadian data analytics firm called Aggregate IQ (“AIQ”) for services provided to campaigners in the EU referendum; and had thereby acted in breach of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (“PPERA”). The Commission concluded that the offences were serious and imposed civil sanctions accordingly. On the same date, the Commission published a report of its investigation into the Appellant (amongst others) concerning campaign funding and spending for the EU referendum (the “Report”). The Appellant now appeals against the Notice pursuant to §6(6) of Schedule 19C PPERA. -

Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics

Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics ETHI Ï NUMBER 113 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, June 12, 2018 Chair Mr. Bob Zimmer 1 Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Tuesday, June 12, 2018 As the chief operating officer, I can assure you, though, that I can speak for AggregateIQ on all matters. Ï (0850) [English] The Vice-Chair (Mr. Nathaniel Erskine-Smith (Beaches—East We've been entirely co-operative with this committee. After our York, Lib.)): Let's begin. last appearance on April 24, we immediately followed up and provided many documents related to the questions you asked. Your Thank you, Mr. Silvester, for attending today. Before we begin chair also asked us to preserve documents in a letter dated May 3. In with your opening statement, I do want to make it known that this our response on the 10th, we told the committee that we had already committee issued a summons to your colleague, Mr. Massingham, preserved the documents in the context of our cooperation with the and he has clearly refused to attend in the face of that summons. Information and Privacy Commissioner of British Columbia and the federal Privacy Commissioner. We respect the important work being Mr. Angus. done by the privacy commissioners and this committee, and wish to Mr. Charlie Angus (Timmins—James Bay, NDP): Thank you, continue a constructive dialogue in support of that work. Mr. Chair. I am very concerned that Mr. Massingham has refused a summons With respect to our discussion with you on the 24th, we were by our committee. -

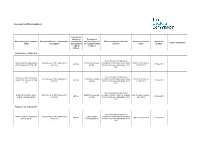

Information on Cases

Casework and Investigations Decision on offence or Decision on Name and type of regulated Potential offence or contravention contravention sanction (imposed Brief summary of reason for Outcome or current Status last Further information entity investigated (by regulated on regulated entity decision status updated entity or or officer) officer) Published on 21 May 2019 The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Kensington Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Offence 21 May 2019 and Chelsea accounting unit) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 case. The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Camborne, Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Redruth and Hayle accounting Offence 21 May 2019 accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 unit) case. The Commission considered, in Scottish Democratic Alliance Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Due for payment by 12 Offence 21 May 2019 (registered political party) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this June 2019 case. Published on 16 April 2019 The Commission considered, in British Resistance (registered Late delivery of 2017 statement of £300 (variable accordance with the enforcement policy, Offence Paid on 23 April 2019 21 May 2019 political party) accounts monetary penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this case. The Commission considered, in Due for payment by 3 The Entertainment Party Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, May 2019. -

Good-Law-Project-Witness-Statement

Statement for the Claimant Witness: Statement: Exhibits: P/bundle Date: IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT BETWEEN: THE QUEEN on the application of The Good Law Project Claimant and The Electoral Commission Defendant WITNESS STATEMENT OF JOLYON MAUGHAM I, Jolyon Maugham QC, director of the Good Law Project, will say as follows: Overview 1. The facts within this witness statement are from matters within my own knowledge except where otherwise stated. The numbers in bold and in square brackets refer to the page numbers of the hearing bundles. Reasons behind the challenge: 2. The Good Law Project is an organisation I set up with the aim of using the law to deliver a progressive society. The three areas the project presently concentrates on are Brexit, tax, and workers’ rights. I campaigned, independently, for Remain in the Referendum. And I continue to believe that the country’s interests would be better served by us remaining in the EU. It is right that I say this. However, it is also true to say that I have a long running and active interest – predating the Referendum – in the proper functioning of ‘institutions’ of Government. My focus was initially on HMRC that being the institution most closely connected to the work I do in my professional life. However, I also wrote, prior to the Referendum, about my attempts to put pressure on the Electoral Commission to discharge what I see as its statutory 2-1 responsibilities in spheres unconnected with the Referendum. And I have written about the functioning of other public institutions, for example, the Office for Budget Responsibility. -

Note on Third Party Regulations in the OSCE Region

Warsaw, 20 April 2020 Note Nr. POLIT/372/2020 www.legislationline.org NOTE ON THIRD PARTY REGULATIONS IN THE OSCE REGION This Note was prepared by Dr Magnus Ohman, Senior Political Finance Adviser and Director, Regional Europe Office, International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) and has benefited from the contribution made by Ms. Lisa Klein, Political Finance Expert OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Ulica Miodowa 10 PL-00-251 Warsaw ph. +48 22 520 06 00 fax. +48 22 520 0605 Note on Third Party Regulations in the OSCE Region TABLE OF CONTENT I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 III. THE CONCEPT OF THIRD PARTIES ................................................................................................. 5 IV. REASONS FOR REGULATING THIRD PARTY INVOLVEMENT ......................................................... 7 1. Increasing transparency ........................................................................................................................... 7 2. Ensuring that regulatory objectives are not undermined ......................................................................... 7 3. Increasing equality of opportunity and protecting the role of political parties ....................................... 8 V. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON THIRD PARTY -

Regulating Election Finance a Review by the Committee on Standards in Public Life the Committee on Standards in Public Life

Regulating Election Finance A Review by the Committee on Standards in Public Life The Committee on Standards in Public Life July 2021 Regulating Election Finance A Review by the Committee on Standards in Public Life Chair, Lord Evans of Weardale July 2021 Chair’s foreword Dear Prime Minister, I am pleased to present the 22nd report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life on the regulation of election finance. Digital campaigning is revolutionising the way parties and campaigners engage with voters. But it has also made it harder to track how much is being spent, on what, where and by whom. Questions have been raised, both by those with direct experience of the system and by the public, as to whether the current framework for regulating campaign finance is coherent and proportionate. In regulating election finance it is vital to have effective rules that ensure fairness without designing a system so complex and demanding that it deters those who cannot rely on the support of well-resourced party machinery. Some will think that the recommendations in this report don’t go far enough. Others will think they are too radical. We have sought to take into account the diversity of views that we heard, and make practical recommendations that will lead to tangible improvements to the current system, both for those who must understand and comply with it and for the public, who are entitled to know how money is being spent to influence their vote. We have been guided by the principles that people have told us should underpin the regulation of election finance. -

In the Central London County Court E40cl216 - Mayor's and City of London

If this Transcript is to be reported or published, there is a requirement to ensure that no reporting restriction will be breached. This is particularly important in relation to any case involving a sexual offence, where the victim is guaranteed lifetime anonymity (Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992), or where an order has been made in relation to a young person This Transcript is Crown Copyright. It may not be reproduced in whole or in part other than in accordance with relevant licence or with the express consent of the Authority. All rights are reserved IN THE CENTRAL LONDON COUNTY COURT E40CL216 - MAYOR'S AND CITY OF LONDON Guildhall Buildings Basinghall Street London EC2V 5AR Friday, 19 July 2019 Before: HIS HONOUR JUDGE DIGHT CBE IN THE MATTER OF THE POLITICAL PARTIES, ELECTIONS AND REFERENDUMS ACT 2000; and THE POLITICAL PARTIES, ELECTIONS AND REFERENUDMS (CIVIL SANCTIONS) ORDER 2010 and IN THE MATTER OF AN APPEAL AGAINST THE DECISION TO IMPOSE DISCRETIONARY PENALTIES BETWEEN : DARREN GRIMES Appellant - and - THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION Respondent _________ MR T. STRAKER QC and MR F. HOAR (instructed by Saunders Law) appeared on behalf of the Appellant. SIR J. EADIE QC, MR R. MEHTA and MR A. RATAN (instructed by Fieldfisher) appeared on behalf of the Respondent. __________ JUDGMENT JUDGE DIGHT: 1 By this appeal Mr Grimes challenges the imposition on him by the Electoral Commission, in a final notice dated the 17th July 2018, of what are known as discretionary requirements in the total sum of £20,000 in respect of two offences which they found him to have committed in the reporting of expenditure in the campaign expenditure return filed as a result of participation by him and by an entity called BeLeave in the European referendum which took place on the 23rd June 2016. -

Constitution Unit Monitor 73 / November 2019

1 Constitution Unit Monitor 73 / November 2019 That being in place, Labour reluctantly agreed to an On the brink election (see page 6), which it is fighting on a pledge to hold another Brexit referendum. The Liberal Democrats With a general election scheduled for 12 December, want to revoke Article 50 in the unlikely event that they the UK could be at a crucial turning point. Or, of secure a majority, or otherwise hold a referendum. course, not: with the polls uncertain, another hung parliament is a real possibility. The UK appeared closer In recent months much in British politics has already to agreeing terms for leaving the EU in late October felt close to breaking point. While Theresa May fared than previously, after Prime Minister Boris Johnson badly in navigating parliament as the leader of a minority negotiated a revised deal (see page 3) and the House government (only in the final stages seeking agreement of Commons backed his Withdrawal Agreement Bill at with other parties), Johnson seems actively to have second reading (see page 5). But when MPs refused to sought confrontation with parliament. This is, to say the accept Johnson’s demand that they rush the legislation least, an unorthodox strategy in a system where the through in three days, he refused to accord them more government depends on the Commons’ confidence to time, and demanded – as he had twice in September survive. It is the very reverse of what would normally – a general election. A further extension of the Article be expected under a minority government. -

The Great British Brexit Robbery: How Our Democracy Was Hijacked

The Observer The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked A shadowy global operation involving big data, billionaire friends of Trump and the disparate forces of the Leave campaign influenced the result of the EU referendum. As Britain heads to the polls again, is our electoral process still fit for purpose? by Carole Cadwalladr Sunday 7 May 2017 04.00 EDT This article is the subject of legal complaints on behalf of Cambridge Analytica LLC and SCL Elections Limited. “The connectivity that is the heart of globalisation can be exploited by states with hostile intent to further their aims.[…] The risks at stake are profound and represent a fundamental threat to our sovereignty.” Allex Younger,, head of MI6,, December,, 2016 “It’s not MI6’s job to warn of internal threats. It was a very strange speech. Was it one branch of the intelligence services sending a shot across the bows of another? Or was it pointed at Theresa May’s government? Does she know something she’s not telling us?” Seniior iintelllliigence anallyst,, Apriill 2017 In January 2013, a young American postgraduate was passing through London when she was called up by the boss of a firm where she’d previously interned. The company, SCL Elections, went on to be bought by Robert Mercer, a secretive hedge fund billionaire, renamed Cambridge Analytica, and achieved a certain notoriety as the data analytics firm that played a role in both Trump and Brexit campaigns. But all of this was still to come. London in 2013 was still basking in the afterglow of the Olympics.