Ecology and Management of European Corn Borer in Iowa Field Corn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy of Pheromones for Managing of the Mediterranean Flour Moth

12th International Working Conference on Stored Product Protection (IWCSPP) in Berlin, Germany, October 7-11, 2018 HOSSEININAVEH, V., BANDANI, A.R., AZMAYESHFARD, P., HOSSEINKHANI, S. UND M. KAZZAZI, 2007. Digestive proteolytic and amylolytic activities in Trogoderma granarium Everts (Dermestidae: Coleoptera). J. Stored Prod. Res., 43: 515-522. ISHAAYA, I. UND R. HOROWITZ, 1995. Pyriproxyfen, a novel insect growth regulator for controlling whiteflies. Mechanism and resistance management. Pestic. Sci., 43: 227–232. ISHAAYA, I., BARAZANI, A., KONTSEDALOV, S. UND A.R. HOROWITZ, 2007. Insecticides with novel mode of action: Mechanism, selectivity and cross-resistance. Entomol. Res., 37: 148-152. IZAWA, Y., M. UCHIDA, T. SUGIMOTO AND T. ASAI, 1985. Inhibition of Chitin Biosynthesis by buprofezin analogs in relation to their activity controlling Nilaparvata lugens. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol., 24: 343-347. KLJAJIC, P. UND I. PERIC, 2007. Effectiveness of wheat-applied contact insecticide against Sitophilus granarius (L.) originating from different populations. J. Stored Prod. Res., 43: 523-529. KONNO, T., 1990. Buprofezin: A reliable IGR for the control of rice pests. Soci. Chem. Indus., 23: 212 - 214. KOSTYUKOVSKY, M. UND A. TROSTANETSKY, 2006. The effect of a new chitin synthesis inhibitor, novaluron, on various developmental stages ofTribolium castaneum (Herbst). J. Stored Prod. Res., 42: 136-148. KOSTYUKOVSKY, M., CHEN, B., ATSMI, S. UND E. SHAAYA, 2000. Biological activity of two juvenoids and two ecdysteroids against three stored product insects. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol., 30: 891-897. LIANG, P., CUI, J.Z., YANG, X.Q. UND X.W. GAO, 2007. Effects of host plants on insecticide susceptibility and carboxylesterase activity in Bemisia tabaci biotype B and greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum. -

European Corn Borer, Ostrinia Nubilalis (Hübner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L

EENY156 European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution flights and oviposition typically occur in May, late June, and August. In locations with four generations, adults are active First found in North America near Boston, Massachusetts in April, June, July, and August-September. in 1917, European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner), now has spread as far west as the Rocky Mountains in both Egg Canada and the United States, and south to the Gulf Coast Eggs are deposited in irregular clusters of about 15 to 20. states. European corn borer is thought to have originated in The eggs are oval, flattened, and creamy white in color, Europe, where it is widespread. It also occurs in northern usually with an iridescent appearance. The eggs darken Africa. The North American European corn borer popula- to a beige or orangish tan color with age. Eggs normally tion is thought to have resulted from multiple introductions are deposited on the underside of leaves, and overlap like from more than one area of Europe. Thus, there are at least shingles on a roof or fish scales. Eggs measure about 1.0 two, and possibly more, strains present. This species occurs mm in length and 0.75 m in width. The developmental infrequently in Florida. threshold for eggs is about 15°C. Eggs hatch in four to nine days. Life Cycle and Description The number of generations varies from one to four, with only one generation occurring in northern New England and Minnesota and in northern areas of Canada, whereas three to four generations occur in Virginia and other southern locations. -

Twenty-Five Pests You Don't Want in Your Garden

Twenty-five Pests You Don’t Want in Your Garden Prepared by the PA IPM Program J. Kenneth Long, Jr. PA IPM Program Assistant (717) 772-5227 [email protected] Pest Pest Sheet Aphid 1 Asparagus Beetle 2 Bean Leaf Beetle 3 Cabbage Looper 4 Cabbage Maggot 5 Colorado Potato Beetle 6 Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm) 7 Cutworm 8 Diamondback Moth 9 European Corn Borer 10 Flea Beetle 11 Imported Cabbageworm 12 Japanese Beetle 13 Mexican Bean Beetle 14 Northern Corn Rootworm 15 Potato Leafhopper 16 Slug 17 Spotted Cucumber Beetle (Southern Corn Rootworm) 18 Squash Bug 19 Squash Vine Borer 20 Stink Bug 21 Striped Cucumber Beetle 22 Tarnished Plant Bug 23 Tomato Hornworm 24 Wireworm 25 PA IPM Program Pest Sheet 1 Aphids Many species (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Origin: Native) Insect Description: 1 Adults: About /8” long; soft-bodied; light to dark green; may be winged or wingless. Cornicles, paired tubular structures on abdomen, are helpful in identification. Nymph: Daughters are born alive contain- ing partly formed daughters inside their bodies. (See life history below). Soybean Aphids Eggs: Laid in protected places only near the end of the growing season. Primary Host: Many vegetable crops. Life History: Females lay eggs near the end Damage: Adults and immatures suck sap from of the growing season in protected places on plants, reducing vigor and growth of plant. host plants. In spring, plump “stem Produce “honeydew” (sticky liquid) on which a mothers” emerge from these eggs, and give black fungus can grow. live birth to daughters, and theygive birth Management: Hide under leaves. -

Big Creek Lepidoptera Checklist

Big Creek Lepidoptera Checklist Prepared by J.A. Powell, Essig Museum of Entomology, UC Berkeley. For a description of the Big Creek Lepidoptera Survey, see Powell, J.A. Big Creek Reserve Lepidoptera Survey: Recovery of Populations after the 1985 Rat Creek Fire. In Views of a Coastal Wilderness: 20 Years of Research at Big Creek Reserve. (copies available at the reserve). family genus species subspecies author Acrolepiidae Acrolepiopsis californica Gaedicke Adelidae Adela flammeusella Chambers Adelidae Adela punctiferella Walsingham Adelidae Adela septentrionella Walsingham Adelidae Adela trigrapha Zeller Alucitidae Alucita hexadactyla Linnaeus Arctiidae Apantesis ornata (Packard) Arctiidae Apantesis proxima (Guerin-Meneville) Arctiidae Arachnis picta Packard Arctiidae Cisthene deserta (Felder) Arctiidae Cisthene faustinula (Boisduval) Arctiidae Cisthene liberomacula (Dyar) Arctiidae Gnophaela latipennis (Boisduval) Arctiidae Hemihyalea edwardsii (Packard) Arctiidae Lophocampa maculata Harris Arctiidae Lycomorpha grotei (Packard) Arctiidae Spilosoma vagans (Boisduval) Arctiidae Spilosoma vestalis Packard Argyresthiidae Argyresthia cupressella Walsingham Argyresthiidae Argyresthia franciscella Busck Argyresthiidae Argyresthia sp. (gray) Blastobasidae ?genus Blastobasidae Blastobasis ?glandulella (Riley) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.1) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.2) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.3) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.4) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.5) Blastobasidae Holcocera (sp.6) Blastobasidae Holcocera gigantella (Chambers) Blastobasidae -

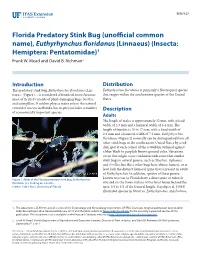

Florida Predatory Stink Bug (Unofficial Common Name), Euthyrhynchus Floridanus(Linnaeus) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Frank W

EENY157 Florida Predatory Stink Bug (unofficial common name), Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Frank W. Mead and David B. Richman2 Introduction Distribution The predatory stink bug, Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Lin- Euthyrhynchus floridanus is primarily a Neotropical species naeus) (Figure 1), is considered a beneficial insect because that ranges within the southeastern quarter of the United most of its prey consists of plant-damaging bugs, beetles, States. and caterpillars. It seldom plays a major role in the natural control of insects in Florida, but its prey includes a number Description of economically important species. Adults The length of males is approximately 12 mm, with a head width of 2.3 mm and a humeral width of 6.4 mm. The length of females is 12 to 17 mm, with a head width of 2.4 mm and a humeral width of 7.2 mm. Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Figure 2) normally can be distinguished from all other stink bugs in the southeastern United States by a red- dish spot at each corner of the scutellum outlined against a blue-black to purplish-brown ground color. Variations occur that might cause confusion with somewhat similar stink bugs in several genera, such as Stiretrus, Oplomus, and Perillus, but these other bugs have obtuse humeri, or at least lack the distinct humeral spine that is present in adults of Euthyrhynchus. In addition, species of these genera Figure 1. Adult of the Florida predatory stink bug, Euthyrhynchus known to occur in Florida have a short spine or tubercle floridanus (L.), feeding on a beetle. situated on the lower surface of the front femur behind the Credits: Lyle J. -

2020 Painted Lady Instar Id 4June

Painted lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) instar identification and life history with head capsule photo, larval and pupal length by Vera Krischik, June 2020. Even though they are often thought of as the thistle butterflies and a majority of their eggs are laid on thistles, the larvae feed, and can be reared, on a huge and varied number of plants, and plant types, in several different families. Painted ladies overwinter in the deserts along the Mexican border, where they breed and lay their eggs on annual plants that grow quickly after the winter rains start. The adults then move northward in a migration that varies greatly from year to year; in heavy rainfall years hundreds of millions of adults fly. In 2019 a large migration occurs as did in 2005, when an estimated one billion individual painted ladies migrated north. These butterflies emerge from the pupa with a yellow fat reserve that allows them to fly from dawn to dusk without stopping to feed. As their fat reserve dwindles, they stop migrating, begin to feed, and become sexually active. A reverse, but much more casual migration, occurs in late summer, when the butterflies head south again, feeding and breeding along the way (homegroundhabitats.org/painted-lady-butterflies). Second instar 5-7 mm Third instar 5-12 mm Fourth instar 13-16 mm Fifth instar 20-36 mm Chrysalis 48-60 mm Chrysalis black death+ Adult male Adult female++ Mating Eggs on leaf Egg hatching Adult males have a Adult females have a slender abdomen wider abdomen compared to females; in compared to males; in males the front legs are females the front legs reduced with short are reduced with spines brush-like hairs; used to drum and find wingspan 50-56mm maters; wingspan 50- 56mm Photos: instars, chrysalis, eggs (Krischik lab), adult male (Wikimedia), adult female (Mary Legg, Bugwood.org). -

Insect Order ID: Hemiptera (Scale, Mealybugs)

Return to insect order home Page 1 of 3 Visit us on the Web: www.gardeninghelp.org Insect Order ID: Hemiptera (Scale, Mealybugs) Life Cycle–Usually gradual metamorphosis (incomplete or simple). Eggs are laid in clusters and hidden under the scale-like covering of the adult female. First instar larvae (crawlers) are active. Later instars of some species lose their legs and their ability to move and look more and more like adults as they grow and molt. Males go through a pre-adult resting stage (a kind of pupal stage), during which they develop wings. Wingless adult females mate with winged males, then lay eggs. In some species, metamorphosis is more complex as some are hermaphroditic, others are parthenogenic and others give birth to live young (certain species of mealybugs). Adults & Larvae–It can be hard to tell adults from larvae. Most are covered in wax. On soft scale this can wear off. On armored scale the wax combines with molted skin to form a hard protective covering. Adult males, like gnats, are tiny and have only two wings; however, unlike gnats and other Dipterans (true flies), they lack halteres. Females are wingless. Many lose their legs and antennae soon after the crawler stage, and never move again; mealybugs (a kind of soft scale) retain their legs. Males die after mating. Females usually die soon after laying eggs. Some mealybugs give birth to live young, so multiple stages may be present at the same time. (Click images to enlarge or orange text for more information.) Small insects, hard to tell Soft scale coated with wax Soft scale with wax worn off Armored scale combines adults from larvae that wears thin with age hardened wax & cast skins Mealybugs like to congregate, especially in leaf axils Mealybugs remain mobile Most species are legless Return to insect order home Page 2 of 3 Eggs–Most lay eggs under their waxy, scaly covering and then die. -

Phylogeny and Evolution of Lepidoptera

EN62CH15-Mitter ARI 5 November 2016 12:1 I Review in Advance first posted online V E W E on November 16, 2016. (Changes may R S still occur before final publication online and in print.) I E N C N A D V A Phylogeny and Evolution of Lepidoptera Charles Mitter,1,∗ Donald R. Davis,2 and Michael P. Cummings3 1Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742; email: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 3Laboratory of Molecular Evolution, Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017. 62:265–83 Keywords Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017.62. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Hexapoda, insect, systematics, classification, butterfly, moth, molecular ento.annualreviews.org systematics This article’s doi: Access provided by University of Maryland - College Park on 11/20/16. For personal use only. 10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035125 Abstract Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. Until recently, deep-level phylogeny in Lepidoptera, the largest single ra- All rights reserved diation of plant-feeding insects, was very poorly understood. Over the past ∗ Corresponding author two decades, building on a preceding era of morphological cladistic stud- ies, molecular data have yielded robust initial estimates of relationships both within and among the ∼43 superfamilies, with unsolved problems now yield- ing to much larger data sets from high-throughput sequencing. Here we summarize progress on lepidopteran phylogeny since 1975, emphasizing the superfamily level, and discuss some resulting advances in our understanding of lepidopteran evolution. -

Small Ermine Moths Role of Pheromones in Reproductive Isolation and Speciation

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Small Ermine Moths Role of Pheromones in Reproductive Isolation and Speciation MARJORIE A. LIÉNARD and CHRISTER LÖFSTEDT INTRODUCTION Role of antagonists as enhancers of reproductive isolation and interspecific interactions THE EVOLUTION TOWARDS SPECIALIZED HOST-PLANT ASSOCIATIONS SUMMARY: AN EMERGING MODEL SYSTEM IN RESEARCH ON THE ROLE OF SEX PHEROMONES IN SPECIATION—TOWARD A NEW SEX PHEROMONES AND OTHER ECOLOGICAL FACTORS “SMALL ERMINE MOTH PROJECT”? INVOLVED IN REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION Overcoming the system limitations Overview of sex-pheromone composition Possible areas of future study Temporal and behavioral niches contributing to species separation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS PHEROMONE BIOSYNTHESIS AND MODULATION REFERENCES CITED OF BLEND RATIOS MALE PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BEHAVIORAL RESPONSE Detection of pheromone and plant compounds Introduction onomic investigations were based on examination of adult morphological characters (e.g., wing-spot size and color, geni- Small ermine moths belong to the genus Yponomeuta (Ypo- talia) (Martouret 1966), which did not allow conclusive dis- nomeutidae) that comprises about 75 species distributed glob- crimination of all species, leading to recognition of the so- ally but mainly in the Palearctic region (Gershenson and called padellus-species complex (Friese 1960) which later Ulenberg 1998). These moths are a useful model to decipher proved to include five species (Wiegand 1962; Herrebout et al. the process of speciation, in particular the importance of eco- 1975; Povel 1984). logical adaptation driven by host-plant shifts and the utiliza- In the 1970s, “the small ermine moth project” was initiated tion of species-specific pheromone mating-signals as prezy- to include research on many aspects of the small ermine gotic reproductive isolating mechanisms. -

European Corn Borer (Order: Lepidoptera, Family: Crambidae, Ostrinia Nubilalis (Hubner))

European corn borer (Order: Lepidoptera, Family: Crambidae, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hubner)) Description: Adult: The moths are fairly small, with males having a wingspan of 20-26 mm and females 25-34 mm. Adults caught in south Georgia are generally smaller than the ‘typical’ European corn borer from the mid-west corn belt. Females are pale-yellow to light brown, with darker zig-zag lines across the forewing and hind wing. Males are darker, usually pale brown, with dark zig- zag lines across the forewing and hind wing. Both sexes also have yellowish to gold colored patches on the wings, which are more apparent against the darker background in the male. Immature stages: Eggs are oval, flattened and creamy white when first laid and darken with age. They are deposited in small clusters with the eggs overlapped like fish scales. Larvae tend to be light brown or pinkish-gray, European corn borer adult. with a brown to black head capsule. Full grown larvae are about 2 cm in length. The body is marked with darker circles on each segment along the midline of the back. Larvae are frequently referred to has having a ‘greasy’ look. Larvae can be easily confused with other borers present in plant stalks. Biology: Life cycle: Eggs are generally deposited in irregular clusters of about 15 to 20 on the underside of leaves and hatch in 4 to 9 days depending on the temperature. Larvae usually develop through 5 or 6 instars with a development period of over 30 days and a pupal stage of about 12 days. -

Spined Soldier Bug

Beneficial Species Profile Photo credit: Russ Ottens, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org Common Name: Spined soldier bug Scientific Name: Podisus maculiventris Order and Family: Hemiptera; Pentatomidae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg 1 mm Around the operculum (lid/covering) on the egg there are long projections; eggs laid in numbers of 17 -70 in oval masses; cream to black in color. Larva/Nymph 1.3 – 10 mm 1st and 2nd instars: black head and thorax; reddish abdomen; black dorsal and lateral plates. Younger instars are gregarious; cannibalistic. 3rd instar: black head and thorax; reddish abdomen with black, orange, and white bar-shaped and lateral markings 4th instar: similar to 3rd instar; wing pads noticeable 5th instar: prominent wing pads; mottled brown head and thorax; white or tan and black markings on abdomen. Adult 11 mm Spine on each shoulder; mottled brown body color; females larger than males; 2 blackish dots at the 3rd apical (tip) of each hind femur; 1-3 generations a year. Pupa (if applicable) Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Nymph and adult: Piercing-sucking Host/s: Spined soldier bugs are predators and feed on many species of insects including the larval stage of beetles and moths. These insects are found on many different crops including alfalfa, soybeans, and fruit. Some important pest insect larvae prey include Mexican bean beetle larvae, European corn borer, imported cabbageworm, fall armyworm, corn earworm, and Colorado potato beetle larvae. If there is not enough prey, the spined soldier bug may feed on plant juices, but this does not damage the plant. -

Determination of the Lethal High Temperature for the Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

Determination of the lethal high temperature for the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Y. PELLETIER Agriculture andAgri-Food Canada, Research Centre, P.D. Box 20280, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada E3B 4Z7. Received 22 January 1998; accepted 21 August 1998. Pelletier, Y. 1998. Determination ofthe lethal high temperature for INTRODUCTION the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Can. Agric. Eng. 40:185-189. The susceptibility of insects to high Temperature has a profound effect on living organisms. To a temperatures has been used to develop control methods for pests in large extend, the temperature ofan insect is detennined by the stored products and crops. Recently, microwaves and propane flamers temperature ofits surrounding environment (May 1985). Each were evaluated as control techniques for the Colorado potato beetle, insect species can function nonnally within a specific range of Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say). These methods aim to increase the temperatures. Ifthe body temperature increases above the upper body temperature of the insect above its lethal threshold. The lethal limit ofthat temperature range, the insect may experience heat high temperature for six stages of the Colorado potato beetle was torpor and eventually death. The relative sensitivity ofinsects evaluated by exposing the insects to either warm water or hot air. The to high temperatures has lead to the development of control lethal temperature obtained by immersing insects in warm water was methods that wann the air or the water surrounding the insect up to 5.2 °C lower than with hot air. The difference in the LT95 above its lethal temperature. Vaporheat, hot air, and immersion between the warm water and hot air tests varied with the size ofthe insect, the larger stages showing a larger difference.