Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

They Hate US for Our War Crimes: an Argument for US Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights

UIC Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 2019 They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the ost-HumanP Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) Michael Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael Drake, They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEY HATE U.S. FOR OUR WAR CRIMES: AN ARGUMENT FOR U.S. RATIFICATION OF THE ROME STATUTE IN LIGHT OF THE POST-HUMAN RIGHTS ERA MICHAEL DRAKE* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1012 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................ 1014 A. Continental Disparities ......................................... 1014 1. The International Process in Africa ............... 1014 2. The National Process in the United States of America ............................................................ 1016 B. The Rome Statute, the ICC, and the United States ................................................................................. 1020 1. An International Court to Hold National Leaders Accountable ...................................................... 1020 2. The Aims and Objectives of the Rome Statute .......................................................................... 1021 3. African Bias and U.S. -

Download Transcript

Gaslit Nation Transcript 17 February 2021 Where Is Christopher Wray? https://www.patreon.com/posts/wheres-wray-47654464 Senator Ted Cruz: Donald seems to think he's Michael Corleone. That if any voter, if any delegate, doesn't support Donald Trump, then he's just going to bully him and threaten him. I don't know if the next thing we're going to see is voters or delegates waking up with horse's heads in their bed, but that doesn't belong in the electoral process. And I think Donald needs to renounce this incitement of violence. He needs to stop asking his supporters at rallies to punch protestors in the face, and he needs to fire the people responsible. Senator Ted Cruz: He needs to denounce Manafort and Roger Stone and his campaign team that is encouraging violence, and he needs to stop doing it himself. When Donald Trump himself stands up and says, "If I'm not the nominee, there will be rioting in the streets.", well, you know what? Sol Wolinsky was laughing in his grave watching Donald Trump incite violence that has no business in our democracy. Sarah Kendzior: I'm Sarah Kendzior, the author of the bestselling books The View from Flyover Country and Hiding in Plain Sight. Andrea Chalupa: I'm Andrea Chalupa, a journalist and filmmaker and the writer and producer of the journalistic thriller Mr. Jones. Sarah Kendzior: And this is Gaslit Nation, a podcast covering corruption in the United States and rising autocracy around the world, and our opening clip was of Senator Ted Cruz denouncing Donald Trump's violence in an April 2016 interview. -

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She Overcame Her Fears and Shyness to Win Miss America 1967, Launching Her Career in Media and Government

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She overcame her fears and shyness to win Miss America 1967, launching her career in media and government Chapter 01 – 0:52 Introduction Announcer: As millions of television viewers watch Jane Jayroe crowned Miss America in 1967, and as Bert Parks serenaded her, no one would have thought she was actually a very shy and reluctant winner. Nor would they know that the tears, which flowed, were more of fright than joy. She was nineteen when her whole life was changed in an instant. Jane went on to become a well-known broadcaster, author, and public official. She worked as an anchor in TV news in Oklahoma City and Dallas, Fort Worth. Oklahoma governor, Frank Keating, appointed her to serve as his Secretary of Tourism. But her story along the way was filled with ups and downs. Listen to Jane Jayroe talk about her struggle with shyness, depression, and a failed marriage. And how she overcame it all to lead a happy and successful life, on this oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 8:30 Grandparents John Erling: My name is John Erling. Today’s date is April 3, 2014. Jane, will you state your full name, your date of birth, and your present age. Jane Jayroe: Jane Anne Jayroe-Gamble. Birthday is October 30, 1946. And I have a hard time remembering my age. JE: Why is that? JJ: I don’t know. I have to call my son, he’s better with numbers. I think I’m sixty-seven. JE: Peggy Helmerich, you know from Tulsa? JJ: I know who she is. -

National Occupational Research Agenda Update July, 1997

National Occupational Research Agenda Update July, 1997 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Howard Hoffman (National Institute on Rolf Eppinger (National Highway Transporta- NORA Teams Deafness and Communicative Disorders) tion Safety Administration) John Casali (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Stephen Luchter (National Highway State University) Transportation Safety Administration) Bold type indicates team leader(s) Patricia Brogan (Ford Motor Company) Tim Pizatella (NIOSH) 1. Allergic & Irritant Dermatitis Randy Tubbs (NIOSH) 8. Indoor Environment Boris Lushniak (NIOSH) Mark Mendell (NIOSH) Alan Moshell (National Institute of Arthritis 5. Infectious Diseases William Fisk (Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory) and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) William Cain (University of California San Carol Burnett (NIOSH) Robert Mullan (NIOSH) Diego) David Bernstein (University of Cincinnati) William Denton (Denton International) Cynthia Hines (NIOSH) Frances Storrs (Oregon Health Sciences Craig Shapiro (National Center for Infectious Darryl Alexander (American Federation of University) Diseases) Teachers) G. Frank Gerberick (Proctor & Gamble Adelisa Panlilio (National Center for David Spannbauer (General Services Company) Infectious Diseases) Administration) Mark Boeniger (NIOSH) Jack Parker (NIOSH) Donald Milton (Harvard University) Michael Luster (NIOSH) Joel Breman (Fogarty -

Post-Postfeminism?: New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times

FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 16, NO. 4, 610–630 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293 Post-postfeminism?: new feminist visibilities in postfeminist times Rosalind Gill Department of Sociology, City University, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article contributes to debates about the value and utility Postfeminism; neoliberalism; of the notion of postfeminism for a seemingly “new” moment feminism; media magazines marked by a resurgence of interest in feminism in the media and among young women. The paper reviews current understandings of postfeminism and criticisms of the term’s failure to speak to or connect with contemporary feminism. It offers a defence of the continued importance of a critical notion of postfeminism, used as an analytical category to capture a distinctive contradictory-but- patterned sensibility intimately connected to neoliberalism. The paper raises questions about the meaning of the apparent new visibility of feminism and highlights the multiplicity of different feminisms currently circulating in mainstream media culture—which exist in tension with each other. I argue for the importance of being able to “think together” the rise of popular feminism alongside and in tandem with intensified misogyny. I further show how a postfeminist sensibility informs even those media productions that ostensibly celebrate the new feminism. Ultimately, the paper argues that claims that we have moved “beyond” postfeminism are (sadly) premature, and the notion still has much to offer feminist cultural critics. Introduction: feminism, postfeminism and generation On October 2, 2015 the London Evening Standard (ES) published its first glossy magazine of the new academic year. With a striking red, white, and black cover design it showed model Neelam Gill in a bright red coat, upon which the words “NEW (GEN) FEM” were superimposed in bold. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM 02/12/21 Friday This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Lincoln Project Faces Exodus of Advisers Amid Sexual Harassment Coverup Scandal by Morgan Artvukhina Donald Trump was a political outsider in the 2016 US presidential election, and many Republicans refused to accept him as one of their own, dubbing themselves "never-Trump" Republicans. When he sought re-election in 2020, the group rallied in support of his Democratic challenger, now the US president, Joe Biden. An increasing number of senior figures in the never-Trump political action committee The Lincoln Project (TLP) have announced they are leaving, with three people saying Friday they were calling it quits in the wake of a sexual assault scandal involving co-founder John Weaver. "I've always been transparent about all my affiliations, as I am now: I told TLP leadership yesterday that I'm stepping down as an unpaid adviser as they sort this out and decide their future direction and organization," Tom Nichols, a “never-Trump” Republican who supported the group’s effort to rally conservative support for US President Joe Biden in the 2020 election, tweeted on Friday afternoon. Nichols was joined by another adviser, Kurt Bardella and by Navvera Hag, who hosted the PAC’s online show “The Lincoln Report.” Late on Friday, Lincoln Project co-founder Steve Schmidt reportedly announced his resignation following accusations from PAC employees that he handled the harassment scandal poorly, according to the Daily Beast. -

Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative

Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative University of Warwick 20-21 September 2012 Convenor Dr Katherine Angel (University of Warwick) Kindly supported by the Wellcome Trust and Warwick Centre for the History of Medicine’s Strategic Award Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative University of Warwick 20-21 September 2012 IAS, Millburn House Contents Page Conference Logistics 3 Conference Information 4 Provisional Programme 5 Abstracts: Dr Adrian Bingham 6 Impossible to Shift? Feminism and the ‘Page 3 Girl’ Dr Laura King 6 Fathers as Feminists: Fatherhood and (Post) Feminism in Britain Professor Barbara Marshall 7 Post-Feminism, Post-Ageing, and Bodies-in-Time Dr Jonathan Dean 7 Resistance and Hope in the ‘Cultural Space of Post-Feminism’ Dr Laura Schwartz ‘Standing in the Shadow of Your Sister: Reflections on a new generation of feminism’ 7 Professor Kathy Davis Wetlands: Postfeminist Sexuality and the Illusion of Empowerment 7 Ms Allie Carr How Do I Look? 8 2 Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative Organised by the Centre for the History of Medicine - University of Warwick Venue Institute of Advanced Studies, Millburn House, University of Warwick Millburn House is located two buildings along from University House in the University of Warwick Science Park – it is marked as building 42 on the main campus map (the building is in the top right hand corner of the map). This can be downloaded at: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/about/visiting/maps/campusmap/ Please note that the building numbers on printed versions of the map may be different. Once you arrive at Millburn, use the front entrance shown on the photo and take the staircase opposite you as you enter. -

Introduction 1 Theorizing Women's Singleness: Postfeminism

Notes Introduction 1. See Ringrose and Walkerdine’s work on how the boundaries of femininity are policed, constituting some subject positions – those against which normative femininity comes to be defined – ‘uninhabitable’ (2008, p. 234). 1 Theorizing Women’s Singleness: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism, and the Politics of Popular Culture 1. Lewis and Moon (1997) have observed that women’s singleness is at once glamorized and stigmatized, however I suggest, and explore how, this is a particular feature of postfeminist media culture. 2. As Jill Reynolds argues, ‘the cultural context today incorporates new repre- sentations of singleness while continuing to draw on older, more devalued notions that being single is a problem for women: generally to be resolved through commitment to a heterosexual relationship’ (2008, p. 2). 3. In early feminist studies of how women were represented in the media, the ‘images of women’ style criticism dominated, arguing that women were mis- represented in and through the mainstream media and that such ‘negative’ rep- resentations had deleterious effects on the women who consumed them. This is a position that has been thoroughly critiqued and replaced by more nuanced approaches to both signification and consumption. See Walters’ chapter ‘From Images of Women to Woman as Image’ for a rehearsal of these debates (1995). 4. For example, in her critical text Postfeminisms, Ann Brooks (1997) conceptual- izes it in terms of the intersections of feminism, poststructuralism, postmod- ernism, and postcolonialism. Others have theorized it primarily as a popular manifestation which effectively represents an updated form of antifeminism (Faludi, 1991; Walters, 1995; Kim, 2001). 5. The idea that postfeminism is itself constituted by contradiction, ‘the product of competing discourses and interests’ (Genz & Brabon, 2009, p. -

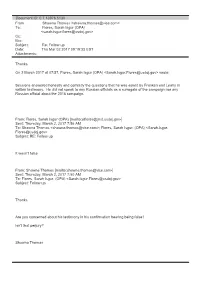

Flores, Sarah Isgur

Document ID: 0.7.13976.5130 From: Shawna Thomas <[email protected]> To: Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) <[email protected]> Cc: Bcc: Subject: Re: Follow up Date: Thu Mar 02 2017 09:19:33 EST Attachments: Thanks. On 2 March 2017 at 07:57, Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) <[email protected]> wrote: Sessions answered honestly and correctly the questions that he was asked by Franken and Leahy in written testimony. He did not speak to any Russian officials as a surrogate of the campaign nor any Russian official about the 2016 campaign. From: Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, March 2, 2017 7:56 AM To: Shawna Thomas <[email protected]>; Flores, Sarah Isgur. (OPA) <Sarah.Isgur. [email protected]> Subject: RE: Follow up It wasn’t false From: Shawna Thomas [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, March 2, 2017 7:50 AM To: Flores, Sarah Isgur. (OPA) <[email protected]> Subject: Follow up Thanks. Are you concerned about his testimony in his confirmation hearing being false? Isn't that perjury? Shawna Thomas DC Bureau Chief - Vice News c: (b)(6) @shawna On Mar 2, 2017, at 6:39 AM, Sarah Isgur Flores <(b)(6) > wrote: cc'ing my do one so you have it. I think its important to note that this was in the regular course of his work on armed services. He met 25 times with ambassadors last year. The day after this meeting, he met with the Ukranian ambassador. The meeting was in his senate office with two defense policy staffers--meaning, this wasn't some secret. -

PR Front Row Trump Show

Publication Date: March 31, 2020 Publicity Contact: Price: $28.00 Amanda Walker, 212-366-2212 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] NOW A NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER “Jonathan Karl is a straight-shooting, fair-minded, and hardworking professional so it’s no surprise he’s produced a book historians will relish.”—Peggy Noonan, Wall Street Journal FRONT ROW AT THE TRUMP SHOW Jonathan Karl Chief White House Correspondent for ABC News EARLY PRAISE FOR FRONT ROW AT THE TRUMP SHOW “Jon Karl is fierce, fearless, and fair. He knows the man, and the office. Front Row at the Trump Show takes us inside the daily challenge of truthful reporting on the Trump WH, revealing what’s at stake with vivid detail and deep insights.” —George Stephanopoulos "In this revealing and personal account of his relationship with our 45th president, we learn what it is really like to be on the White House beat, about the peculiarities of dealing with the personality in the Oval Office, and ultimately the risks and dangers we face at this singular moment in American history." —Mike McCurry, former White House press secretary “No reporter has covered Donald Trump longer and with more energy than Jonathan Karl. It pays off in his account of what he calls the Trump Show with some startling scoops.”—Susan Page, Washington bureau chief, USA Today “The Constitution is strict: It says we must have presidents. Fortunately, we occasionally have reporters as talented as Jonathan Karl—an acute observer and gifted writer—to record what presidents do. Karl is exactly the right journalist to chronicle the 45th president, who is more—to be polite—exotic than his predecessors.” —George F. -

Analyzing Postfeminist Themes in Girls' Magazines

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2021, Volume 9, Issue 2, Pages 27–38 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v9i2.3757 Article What a Girl Wants, What a Girl Needs: Analyzing Postfeminist Themes in Girls’ Magazines Marieke Boschma 1 and Serena Daalmans 1,2,* 1 Department of Communication Science, Radboud University, 6500HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.B.), [email protected] (S.D.) 2 Behavioral Science Institute, Radboud University, 6500HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands * Corresponding author Submitted: 19 October 2020 | Accepted: 22 December 2020 | Published: 23 March 2021 Abstract Girls’ magazines play an important role in the maintenance of gender perceptions and the creation of gender by young girls. Due to a recent resurgence within public discussion and mediated content of feminist, postfeminist, and antifeminist repertoires, centered on what femininity entails, young girls are growing up in an environment in which conflicting mes- sages are communicated about their gender. To assess, which shared norms and values related to gender are articulated in girl culture and to what extent these post/anti/feminist repertoires are prevalent in the conceptualization of girlhood, it is important to analyze magazines as vehicles of this culture. The current study analyzes if and how contemporary post- feminist thought is articulated in popular girl’s magazines. To reach this goal, we conducted a thematic analysis of three popular Dutch teenage girls’ magazines (N = 27, from 2018), Fashionchick, Cosmogirl, and Girlz. The results revealed that the magazines incorporate feminist, antifeminist, and as a result, postfeminist discourse in their content. The themes in which these repertoires are articulated are centered around: the body, sex, male–female relationships, female empower- ment, and self-reflexivity.