Analyzing Postfeminist Themes in Girls' Magazines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Post-Postfeminism?: New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times

FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 16, NO. 4, 610–630 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293 Post-postfeminism?: new feminist visibilities in postfeminist times Rosalind Gill Department of Sociology, City University, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article contributes to debates about the value and utility Postfeminism; neoliberalism; of the notion of postfeminism for a seemingly “new” moment feminism; media magazines marked by a resurgence of interest in feminism in the media and among young women. The paper reviews current understandings of postfeminism and criticisms of the term’s failure to speak to or connect with contemporary feminism. It offers a defence of the continued importance of a critical notion of postfeminism, used as an analytical category to capture a distinctive contradictory-but- patterned sensibility intimately connected to neoliberalism. The paper raises questions about the meaning of the apparent new visibility of feminism and highlights the multiplicity of different feminisms currently circulating in mainstream media culture—which exist in tension with each other. I argue for the importance of being able to “think together” the rise of popular feminism alongside and in tandem with intensified misogyny. I further show how a postfeminist sensibility informs even those media productions that ostensibly celebrate the new feminism. Ultimately, the paper argues that claims that we have moved “beyond” postfeminism are (sadly) premature, and the notion still has much to offer feminist cultural critics. Introduction: feminism, postfeminism and generation On October 2, 2015 the London Evening Standard (ES) published its first glossy magazine of the new academic year. With a striking red, white, and black cover design it showed model Neelam Gill in a bright red coat, upon which the words “NEW (GEN) FEM” were superimposed in bold. -

From Promise to Proof Promise From

POWER TO DECIDE HIGHLIGHTS OF POP PARTNERSHIPS CULTURE From Promise to Proof HOW THE MEDIA HAS HELPED REDUCE TEEN AND UNPLANNED PREGNANCY TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT US ...................................................................................................4 WHY IT MATTERS .......................................................................................5 SPOTLIGHT ON KEY PARTNERSHIPS ...........................................................7 FREEFORM ..................................................................................................8 COSMOPOLITAN ......................................................................................12 TLC ..............................................................................................................16 SNAPSHOTS OF KEY MEDIA PARTNERSHIPS ...........................................21 SEX EDUCATION ..................................................................................... 22 BLACK-ISH ............................................................................................... 23 ANDI MACK .............................................................................................. 24 MTV ........................................................................................................... 26 AP BIO ....................................................................................................... 28 BUZZFEED—BC ....................................................................................... 29 HULU ........................................................................................................ -

The Shifting Terrain of Sex and Power: from the 'Sexualization of Culture' to #Metoo

Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad The shifting terrain of sex and power: from the ‘sexualization of culture’ to #MeToo Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Gill, Rosalind and Orgad, Shani (2018) The shifting terrain of sex and power: from the ‘sexualization of culture’ to #MeToo. Sexualities , 21 (8). pp. 1313-1324. ISSN 1363-4607 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718794647 © 2018 SAGE Publications This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/91503 Available in LSE Research Online: January 2019 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facil itate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL ( http://eprints.lse.ac.uk ) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the publishe d version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it . The shifting terrain of sex and power: From the ‘sexualization of culture’ to #MeToo Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad It is an honour to be part of the 20 th anniversary celebrations for Sexualities and to have the opportunity to express appreciation for the space the journal has opened up. -

Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative

Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative University of Warwick 20-21 September 2012 Convenor Dr Katherine Angel (University of Warwick) Kindly supported by the Wellcome Trust and Warwick Centre for the History of Medicine’s Strategic Award Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative University of Warwick 20-21 September 2012 IAS, Millburn House Contents Page Conference Logistics 3 Conference Information 4 Provisional Programme 5 Abstracts: Dr Adrian Bingham 6 Impossible to Shift? Feminism and the ‘Page 3 Girl’ Dr Laura King 6 Fathers as Feminists: Fatherhood and (Post) Feminism in Britain Professor Barbara Marshall 7 Post-Feminism, Post-Ageing, and Bodies-in-Time Dr Jonathan Dean 7 Resistance and Hope in the ‘Cultural Space of Post-Feminism’ Dr Laura Schwartz ‘Standing in the Shadow of Your Sister: Reflections on a new generation of feminism’ 7 Professor Kathy Davis Wetlands: Postfeminist Sexuality and the Illusion of Empowerment 7 Ms Allie Carr How Do I Look? 8 2 Looking Back: ‘Post-Feminism’, History, Narrative Organised by the Centre for the History of Medicine - University of Warwick Venue Institute of Advanced Studies, Millburn House, University of Warwick Millburn House is located two buildings along from University House in the University of Warwick Science Park – it is marked as building 42 on the main campus map (the building is in the top right hand corner of the map). This can be downloaded at: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/about/visiting/maps/campusmap/ Please note that the building numbers on printed versions of the map may be different. Once you arrive at Millburn, use the front entrance shown on the photo and take the staircase opposite you as you enter. -

Introduction 1 Theorizing Women's Singleness: Postfeminism

Notes Introduction 1. See Ringrose and Walkerdine’s work on how the boundaries of femininity are policed, constituting some subject positions – those against which normative femininity comes to be defined – ‘uninhabitable’ (2008, p. 234). 1 Theorizing Women’s Singleness: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism, and the Politics of Popular Culture 1. Lewis and Moon (1997) have observed that women’s singleness is at once glamorized and stigmatized, however I suggest, and explore how, this is a particular feature of postfeminist media culture. 2. As Jill Reynolds argues, ‘the cultural context today incorporates new repre- sentations of singleness while continuing to draw on older, more devalued notions that being single is a problem for women: generally to be resolved through commitment to a heterosexual relationship’ (2008, p. 2). 3. In early feminist studies of how women were represented in the media, the ‘images of women’ style criticism dominated, arguing that women were mis- represented in and through the mainstream media and that such ‘negative’ rep- resentations had deleterious effects on the women who consumed them. This is a position that has been thoroughly critiqued and replaced by more nuanced approaches to both signification and consumption. See Walters’ chapter ‘From Images of Women to Woman as Image’ for a rehearsal of these debates (1995). 4. For example, in her critical text Postfeminisms, Ann Brooks (1997) conceptual- izes it in terms of the intersections of feminism, poststructuralism, postmod- ernism, and postcolonialism. Others have theorized it primarily as a popular manifestation which effectively represents an updated form of antifeminism (Faludi, 1991; Walters, 1995; Kim, 2001). 5. The idea that postfeminism is itself constituted by contradiction, ‘the product of competing discourses and interests’ (Genz & Brabon, 2009, p. -

Sexting Or Self-Produced Child Pornography – the Dialogue Continues – Structured Prosecutorial Discretion Within a Multidisciplinary Response

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2010 Sexting or Self-Produced Child Pornography – The Dialogue Continues – Structured Prosecutorial Discretion Within a Multidisciplinary Response Mary Graw Leary The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Graw Leary, Sexting or Self-Produced Child Pornography – The Dialogue Continues – Structured Prosecutorial Discretion Within a Multidisciplinary Response, 17 VA. J. SOC. POL’Y & L. 486 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEXTING OR SELF-PRODUCED CHILD PORNOGRAPHY? THE DIALOG CONTINUES - STRUCTURED PROSECUTORIAL DISCRETION WITHIN A MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESPONSE Mary Graw Leary* CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................... 4 87 I. Clarifying Definitions: "Sexting" vs. Self-Produced Child Pornography ................................................................................ 491 A. Self-Produced Child Pornography ............................................. 491 B . "Sexting" ............................................. -

Magazine World

36 Magazine World The operating environment for SCMP magazines was extremely competitive in 2006. The print media revenue base has matured and the market is saturated with product. With few opportunities for growth, publishers compete for the existing market share of readers and advertisers. This competition is best exemplified in the women’s Maxim China completed its first year of full-scale magazine sector, which experienced another cover price operations. The title performed below expectations but war. To maintain circulation margins, SCMP stuck to its demonstrated growth potential. Maxim China ranked cover price (HK$40) for Cosmopolitan and Harper’s Bazaar. fourth in a third-party study of newsstand sales in the men’s sector. Although volume was small, ad yield per SCMP Hearst page was higher than expected and monthly ad sales Turnover for SCMP Hearst magazines in 2006 was $109.4 progressed in the second half 2006. million, slightly ahead of the 2005 mark. Of this amount, display advertising provided the majority of revenues for Outlook Cosmopolitan, Harper’s Bazaar and CosmoGirl!. Despite challenging market conditions, the outlook for magazines is positive, although ad growth is expected to Coming off two solid years of gains,Cosmopolitan faced moderate in 2007 and pressure on circulation continues. a challenging year that saw a decline in newsstand sales and a modest rise in ad revenues. The cover price war SCMP will devote efforts to enhance revenue growth at combined with an average book size of over 600 pages Harper’s Bazaar. One objective is to improve ad volume affected copy sales. -

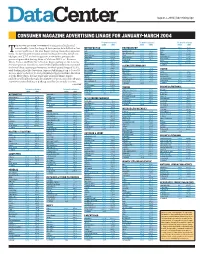

Ad Linage for Jan.-March 2004

Linage 1Q 07-26-04.qxd 7/29/04 3:03 PM Page 1 DataCenter August 2, 2004 | Advertising Age CONSUMER MAGAZINE ADVERTISING LINAGE FOR JANUARY-MARCH 2004 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages he second quarter's numbers for magazines brightened 2004 2003 2004 2003 2004 2003 considerably from the sluggish first quarter detailed below, but METROPOLITAN PHOTOGRAPHY Teen Vogue C. 132.66 80.49 Victoria C. 0.00 70.43 some trendlines of the year began making themselves apparent Boston 269.20 279.50 American Photo (6X) C. 109.02 96.65 T Vogue C. 639.48 715.27 Chicago 263.26 233.15 Outdoor Photographer (10X) 160.59 160.59 early. A near-flat performance at national business titles, which saw W Magazine C. 485.44 438.15 Chicago’s North Shore 126.63 122.37 PC Photo 104.87 120.57 Weight Watchers (6X) C. 148.13 126.18 ad pages sink 2.7% in the first quarter, nonetheless presages the Columbus Monthly 190.65 208.08 Popular Photography C. 380.00 390.76 Woman’s Day (15X) C. 347.02 357.89 Connecticut 136.26 176.50 TOTAL GROUP 754.48 768.57 positive figures that the big-three of McGraw-Hill Cos.' Business YM (11X) C. 108.69 190.16 Diablo 259.11 241.56 % CHANGE -1.83 Week, Forbes, and Time Inc.'s Fortune began putting on the board as TOTAL GROUP 11883.59 12059.13 Indianapolis Monthly 397.00 345.00 % CHANGE -1.46 the year went on. -

A Critical Review of Postfeminist Sensibility

A critical review of postfeminist sensibility Sarah Riley Aberystwyth University Adrienne Evans Coventry University Sinikka Elliott University of British Columbia Carla Rice University of Guelph Jeanne Marecek Swarthmore College This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Riley, S., Evans, A., Elliott, S., Rice, C., & Marecek, J. (2017). A critical review of postfeminist sensibility. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(12), e12367, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12367. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions. Recommended citation: Riley, S., Evans, A., Elliott, S., Rice, C., & Marecek, J. (2017). A critical review of postfeminist sensibility. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(12), e12367. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12367 A critical review of postfeminist sensibility Sarah Riley, Adrienne Evans, Sinikka Elliott, Carla Rice, Jeanne Marecek Abstract This paper critically reviews how feminist academic psychologists, social scientists, and media scholars have developed Rosalind Gill's generative construct “postfeminist sensibility.” We describe the key themes of postfeminist sensibility, a noncoherent set of ideas about femininity, embodiment, and empowerment circulating across a range of media. Ideas that inform women's sense of self, making postfeminist sensibility an important object for psychological study. We then consider research that drew on postfeminist sensibility, focusing on new sexual subjectivities, which developed analysis of agency, empowerment, and the possibilities and limitations in taking up new subjectivities associated with postfeminism, as well as who could take up these subjectivities. We show how such work identified complexities and contradictions in postfeminist sensibility and offer suggestions for how this work might be further developed, particularly by intersectionality‐informed research. -

Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real'

Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research Volume 18 Article 7 2019 Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real' L. Shelley Rawlins Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope Recommended Citation Rawlins, L. Shelley (2019) "Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real'," Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: Vol. 18 , Article 7. Available at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol18/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real' Cover Page Footnote Acknowledgements: I thank my advisor and friend Dr. Craig Gingrich-Philbrook for his invaluable input on this work. I thank my mother Sandy Rawlins for sharing inspiring conversations with me and for her keen editing eye. I appreciate the reviewers’ helpful feedback and thank Kaleidoscope’s editorial staff, especially Shelby Swafford and Alex Davenport, for facilitating this publication process. L. Shelley Rawlins is a Doctoral Candidate at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale This article is available in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol18/iss1/7 Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: ‘The Desert of the Real’ L. Shelley Rawlins Postfeminism is a slippery, contested, ambivalent, and inherently contradictory term – deployed alternately as an “empowering” identity label and critical theoretical lens. -

A Sexual Education: Sex Messages in Seventeen Magazine

A SEXUAL EDUCATION: SEX MESSAGES IN SEVENTEEN MAGAZINE A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Missouri In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts by DALENE ROVENSTINE Professor Mary Kay Blakely, Thesis Committee Chair DECEMBER 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A SEXUAL EDUCATION: SEX MESSAGES IN SEVENTEEN MAGAZINE Presented by Dalene Rovenstine, A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, And hereby certify that in the opinion it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Mary Kay Blakely Dr. Margaret Duffy Professor Jan Colbert Dr. Jennifer Aubrey ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people that helped make this thesis possible, and I know I wouldn’t have made it this far without them. First, I would like to thank Jan Colbert for helping me transition my original thesis idea to what it is now. I would be writing about a completely different topic if it weren’t for her suggestions and ideas. I am forever indebted to my committee chair, Mary Kay Blakely, for all of her guidance throughout the entire thesis process. She took a chance on me, and her help and support has been invaluable. I would not have been able to do this research without her. In addition, I would like to thank my methodologist, Dr. Margaret Duffy, and my outside committee member, Dr. Jennifer Aubrey for their insights and perspective on this work. Their ideas and wisdom helped broaden the topic and scope of this research. I am extremely grateful to all of my professors at the Missouri School of Journalism.