Bound Volume)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

2016 Annual Report

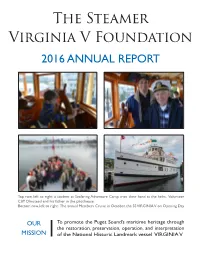

The Steamer Virginia V Foundation 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Top row, left to right: a student at Seafaring Adventure Camp tries their hand at the helm, Volunteer Cliff Olmstead and his father in the pilothouse. Bottom row, left to right: The annual Members Cruise in October, the SS VIRGINIA V on Opening Day. OUR To promote the Puget Sound’s maritime heritage through the restoration, preservation, operation, and interpretation MISSION of the National Historic Landmark vessel VIRGINIA V Vessel Programs Youth Programs The SS Virginia V provides opportunities for kids of all ages to have an interactive learning experience. Elementary and middle school aged kids learn about the Northwest’s maritime history and gain early expo- sure to careers in the maritime industry. The C. Keith Birkenfeld Summer Internships provide opportunities for high school aged students interested in pursuing a ca- reer in the maritime industry to learn about working on a ship, gain usable skills, and to earn funds to help pursue further education. 2016 Highlights: -Produced Seafaring Adventure Camp with MOHAI 2016’s Seafaring Adventure Camp students after -Increased Summer Youth Internships to 4 their program on board the VIRGINIA V. “The VIRGINIA V is the last of her kind, providing a window through which to view the history that shaped our region” -Nina Altman, Fire/Water Tender Open Ship & Visitors In 2016, over twenty thousand visitors set foot on the deck of the VIRGINIA V. Everyone who visits the ship has the opportunity to learn about the history of the “Mosquito Fleet,” maritime transport in the northwest, and the National Historic Landmark vessel VIRGINIA V. -

Washington National Historic Landmarks

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS SURVEY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LISTING OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE WASHINGTON (24) ADVENTURESS (Schooner) ................................................................................................................ 04/11/89 SEATTLE, KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON AMERICAN AND ENGLISH CAMPS, SAN JUAN ISLAND .................................................................. 11/05/61 SAN JUAN COUNTY, WASHINGTON ARTHUR FOSS (Tug) ...........................................................................................................................04/11/89 KIRKLAND, KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON B REACTOR ......................................................................................................................................... 08/19/08 RICHLAND, BENTON COUNTY, WASHINGTON BONNEVILLE DAM HISTORIC DISTRICT (Also in Oregon) ............................................................... 06/30/87 SKAMANIA COUNTY, WASHINGTON and MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON CHINOOK POINT ................................................................................................................................. 07/04/61 PACIFIC COUNTY, WASHINGTON DUWAMISH (Fireboat) ......................................................................................................................... 06/30/89 SEATTLE, KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON FIREBOAT NO. 1 .................................................................................................................................. 06/30/89 TACOMA, PIERCE COUNTY, WASHINGTON FORT -

The Historic Steamer VIRGINIA V 2021 Booking Information

The Historic Steamer VIRGINIA V 2021 Booking Information WHAT'S INCLUDED: Consider our unique operational steamship for your special event or wedding! Underway time, set-up & take-down: Charter contract includes agreed underway schedule, mutually agreed upon set-up time, ½ hour to board your passengers prior to departure, and concludes when the ship returns to the dock. Standard contracts are three hours. Chairs and tables: 4’ rounds that seat six (17), 6’ buffet tables (3), 4’ buffet tables (2), 2’ guest book table (1), bistro tables (4), and 130 white folding chairs are included with the charter. Other items can be rented. Contact City Catering for details. Audio/Visual equipment: A 5-CD changer, mp3 hook-up, tuner, speakers, PA system, hand-held cordless microphone, projector, and projector screen are available. For dancing, a professional PA system is recommended. Special Services: We are honored to have Captain Dale UNDERWAY EXCURSIONS: Pederson available for officiating marriage ceremonies and Our standard underway charter is three hours long and the ship memorial services (contracted separately, fees vary). cruises Lake Union and Lake Washington. Every charter includes 30 minutes of boarding time at no additional charge. NOT Included: Linens, plates, glasses, cutlery, etc. are the responsibility of the charterer and are arranged through the WEDDINGS: caterer. Additional vendors such as DJs and photographers The Steamer Virginia V is an absolutely stunning venue for must be approved by the VIRGINIA V. your special day. Contact us for planning assistance. DOCKSIDE EVENTS: VIRGINIA V is available for dockside events at Lake Union Park. Dockside event rental fee is $450 per hour with a two hour minimum. -

CITY of BAINBRIDGE ISLAND 2014 LODGING/TOURISM FUND PROPOSAL COVER SHEET Project Name: BI Historical Museum Added Hours ______

CITY OF BAINBRIDGE ISLAND 2014 LODGING/TOURISM FUND PROPOSAL COVER SHEET Project Name: BI Historical Museum Added Hours __________________________________________ Name of Applicant Organization: Bainbridge Island Historical Museum_________________________________________ Applicant Organization IRS Chapter 501(c)(3) or 501(c)(6) status and Tax ID Number: 501 (c) (3) Tax ID 91-1037866_______________________________________________ Date of Incorporation as a Washington State Corporation and UBI Number: 1978___UBI Number 601_086_880____________________________________________ Primary Contact: Henry R. Helm, Executive Director____________________________________________ Mailing Address: 215 Ericksen Ave NE, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110__________________________ Email(s): [email protected] __________________________________ Day phone: 206-842-2773 __ Cell phone: 206-612-5105 ________ Number of pages in proposal: _______ Under the definition of “tourism promotion”, which of the following does your proposal include? Please mark all that apply and how much is requested in each category: √ Funding Category Dollar Amount Advertising, publicizing or otherwise distributing information for the purpose of attracting and welcoming tourists Developing strategies to expand tourism Operating tourism promotion agencies Marketing and operations of special festivals or events ⌧ Operation of a tourism-related facility* $15,000 *If the proposal requests funds for operation a tourism-related facility, please indicate the legal owner of that facility: -

2019 Annual Report

THE VIRGINIA V FOUNDATION 2019 ANNUAL REPORT OUR MISSION: To promote the Puget Sound’s maritime heritage through the restoration, preservation, operation, and interpretation of the National Historic Landmark vessel VIRGINIA V. OPERATION As the VIRGINIA V sails the waters of the Puget Sound, she transforms from historical artifact to a living, working vessel. It is her ability to immerse guests in nearly a hundred years of local maritime history that sets the VIRGINIA V apart. In 2019, we were able to share that experience with 4,450 guests who got underway with us. We continue to offer low-cost public cruises, such as Steamship Saturdays in partnership with the Center for Wooden Boats and special narrated cruises in partnership with the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), to give the broader community access to our local waterways and maritime history. We have participated in well-loved traditions including Seattle’s Opening Day, Olympia Harbor Days, the Lake Union Wooden Boat Show, and the Blue Angels Viewing Cruises. The VIRGINIA V provided over 25 private underway charters, seven of which were wedding celebrations. None of this would be possible without the dedication and commitment of our volunteer crew. From the licensed mariners like our captains and chief engineers, to our bartenders, docents, deckhands, and engineers, the VIRGINIA V would not leave the dock without them. 2019 OPERATION HIGHLIGHTS » 55 days underway on the VIRGINIA V » 17,150 total visitors to the vessel » 4,450 guests during public & private cruises » 4,200 volunteer hours donated PRESERVATION The VIRGINIA V continues to be the largest operational, wooden steamboat certified to carry passengers in the United States. -

Cinematic Contextual History of High Noon (1952, Dire Fred Zinnemann) J. M. CAPARROS-LERA SERGIO ALEGRE

Cinematic Contextual History of High Noon (1952, dire Fred Zinnemann) J. M. CAPARROS-LERA SERGIO ALEGRE Cinema must be seen as one of the ways of ideologies of our Century because it shows very well the mentality of men and women who make films. As well as painting, literature and arts, it helps us to understand our time. (Martin A. JACKSON) 0. T.: High Noon. Production: Stanley Kramer Productions, Inc./United Artists (USA,1952). Producers: Stanley Kramer & Carl Foreman. Director: Fred Zinnemann. Screenplay: Carl Foreman, from the story The Tin Star, by John W. Cunningham. Photography: Floyd Crosby. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin. Song: Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darlin', by Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington; singer: Tex Ritter. Art Director: Rudolph Sternad. Editor: Elmo Williams. Cast: Gary Cooper: (Will Kane), Thomas Mitchell (Jonas Henderson), Lloyd Bridges (Harvey Pell), Katy Jurado (Helen Ramirez), Grace Kelly (Amy Kane), Otto Kruge: (Percy Metrick), Lon Chaney, Jr. (Martin Howe), Henry Morgan (Sam Fuller), Ian MacDonald (Frank Miller), Eve McVeagh (Milfred Fuller) Harry Shannon (Cooper), Lee Van Cleef (Jack Colby), Bob Wilke (James Pierce), Sheb Wooley (Ben Miller), Tom London (Sam), Larry Blake (Gillis), Jeanne Blackford (Mrs: Henderson), Guy Beach (Fred), Virginia Christine (Mrs. Simpson), Jack Elam (Charlie), Virginia Farmer (Mrs. Fletcher), Morgan Farley (Priest),Paul Dubov (Scott), Harry Harvey (Coy), Tin Graham (Sawyer), Nolan Leary (Lewis), Tom Greenway (Ezra), Dick Elliot (Kibbee), John Doucete (Trumbull). B/W -85 min. Video distributor: Universal. The post-war American atmosphere and the never well-seen social problem cinema -especially thriller film noir- are the major reasons to understand why during the Forties Hollywood was purged by the self- called the most liberal and democratic government of the world.* Truman's executive order was published in May 12, 1947. -

In the Eye of the European Beholder Maritime History of Olympia And

Number 3 August 2017 Olympia: In the Eye of the European Beholder Maritime History of Olympia and South Puget Sound Mining Coal: An Important Thurston County Industry 100 Years Ago $5.00 THURSTON COUNTY HISTORICAL JOURNAL The Thurston County Historical Journal is dedicated to recording and celebrating the history of Thurston County. The Journal is published by the Olympia Tumwater Foundation as a joint enterprise with the following entities: City of Lacey, City of Olympia, City of Tumwater, Daughters of the American Revolution, Daughters of the Pioneers of Washington/Olympia Chapter, Lacey Historical Society, Old Brewhouse Foundation, Olympia Historical Society and Bigelow House Museum, South Sound Maritime Heritage Association, Thurston County, Tumwater Historical Association, Yelm Prairie Historical Society, and individual donors. Publisher Editor Olympia Tumwater Foundation Karen L. Johnson John Freedman, Executive Director 360-890-2299 Katie Hurley, President, Board of Trustees [email protected] 110 Deschutes Parkway SW P.O. Box 4098 Editorial Committee Tumwater, Washington 98501 Drew W. Crooks 360-943-2550 Janine Gates James S. Hannum, M.D. Erin Quinn Valcho Submission Guidelines The Journal welcomes factual articles dealing with any aspect of Thurston County history. Please contact the editor before submitting an article to determine its suitability for publica- tion. Articles on previously unexplored topics, new interpretations of well-known topics, and personal recollections are preferred. Articles may range in length from 100 words to 10,000 words, and should include source notes and suggested illustrations. Submitted articles will be reviewed by the editorial committee and, if chosen for publication, will be fact-checked and may be edited for length and content. -

Summer 2019 * Vol

SKEETER NEWS A newsletter from The Steamer VIRGINIA V Foundation SUMMER 2019 * VOL. 97, NO. 2 From left to right: 2018 intern Kat in the forward hold; 2017 intern Jack at the engine throttle; and the 2017 internship cohort enjoying the view from the boatdeck. Interns Ahoy! By Margaret Saunders, Programs Manager Please help us welcome our 2019 C. Keith Birkenfeld Another facet of this internship we have sought to summer interns! You may run into these students aboard expand in 2019 is building career skills. This year, our the ship in July and August, as they learn alongside our interns will be attending the week-long Experience crew to work as deckhands and engineers operating and Maritime workshops at Seattle Maritime Academy to maintaining the SS VIRGINIA V. learn more about ocean literacy, shipboard operations, marine safety, survival at sea, marine mechanics, and This is our sixth year hosting the high school internship more. They will be able to network with industry peers program, and we are proud to share with you how the at Youth Maritime Collaborative’s South Lake Union program has grown and changed since its inception. intern fair with MOHAI, the Center for Wooden Boats, We received eighteen applications this year—a new and Northwest Seaport. The Foundation will also host record!—from students all across the Seattle area. By our own career training seminar to help these students expanding our network and outreach, we were able to fill build soft skills like resume writing, networking, and the six internship spots with enthusiastic and deserving interviewing. -

MARITIME INDUSTRY PRESENT MARITIME 101 a Celebration of a Five Star Working Waterfront

NEWSPAPERS IN EDUCATION AND THE SEATTLE MARITIME INDUSTRY PRESENT MARITIME 101 A Celebration of a Five Star Working Waterfront Photos courtesy of Don Wilson, Port of Seattle. Seattle Maritime 101: A Celebration of a Five Star Working Waterfront This Newspapers In Education (NIE) section provides an inside look at the The maritime industry has never been stronger—or more important to our region. maritime industry. From fishing and shipping to the cruise and passenger boat Annually, the industry contributes $30 billion to the state economy, according to a industries, Seattle has always been a maritime community. 2013 study by the Workforce Development Council of Seattle and King County. Our maritime industry is rooted in our rich history of timber production, our The Washington maritime industry is an engine of economic prosperity and location as a trade hub and our proximity to some of the world’s most growth. In 2012, the industry directly employed 57,700 workers across five major productive fisheries. The industry consists of the following sectors: subsectors, paying out wages of $4.1 billion. Maritime firms directly generated over $15.2 billion in revenue. Indirect and induced maritime positions accounted • Maritime Logistics and Shipping for another 90,000 jobs. It adds up to 148,000 jobs in Washington. That’s a lot! • Ship and Boat Building Washington is the most trade-dependent state in the country. According to the • Maintenance and Repair Port of Seattle, four in 10 jobs in Washington are tied to international trade. • Passenger Water Transportation (including Cruise Ships) Our maritime industry relies on a robust and concentrated support system to • Fishing and Seafood Processing fuel its growth. -

Pdgrave Yy^Urt II Houti

THE STAR, Washington, D. c. ** EVENIT'O '» C-6 rtIBAT. JILT M. 10SS Life With Lewis and Clark THE PASSING SHOW One Cliche After Another I *jrf By HARRY lUeAKTHUR good thing "THX VAR HORIZONS "a Part- Medicine Is X-rayed It is. or wm, of R oount picture, produced by WUUsn H \ >int ud WtllUm C. TboißMi dlriettd ¦PF for Merriwether Lewi* and BUI ir Rodelpb Mote. icrecDplxr by Win*ton Siller cod Edmund Hr North, from the Clark that the movie* had not lord, "SocSovco of the Shothonec." il DcllA Oould Emmoni. At tbo CopltU In an Exciting Film yet become popular entertain- 1 Tho on that Cut By JAY CARMODY ment when they set out Ifcrrlwothcr Lowlx Vrtd MirMnmy expedition. they had, it BUI Clerk Charlton Heaton Stranger.” top If ioenjnvcn Donna Reed "Not As A which shot ta the of the best-seller would been a dull trip for Julia Hancock Barbara Hale a nagnMi t < have -WW7 list as a novel, should be equally popular as a film, despite the B flk Everything that occurred Sertaant Can William Demareit them. ebaiboneon . Aim Rood fact of sturdier competition. given them the feel- Cameahwalt Eduardo Norleca Thompson’s by would have Wild Bade Larry Pennell Morton work has been translated to the screen s #-¦¦-. ing that they had been here be- Le Borne Ralph Moody Producer-Director Stanley Kramer with not merely fidelity to its ¦ - ?a« -^:;> fore. Prealdent Jeffcraon Herbert Herea original tart flavor but with a- '~TOri. listen, » *-- can, you ;; 1 You if hear post. Despite them, high-powered cast. -

The Virginia Frontier During The

I / Ti i 7 w ^'if'nu-, 1763, 'fflE VIRGINIA FRONTIER, 1754 - ^tm************* A Dissertation submitted to the Board of University Studies of the Johns Hopkins University in oonformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Louis IQiott Koonta, Second Lieutenant, Infantry, Education Section, General Staff, U. S. Army. Baltimore, Maryland 1920 I ; 11 OHE VIliCilNIA PRC5KTIEH, 1754 - 1763 GONOEUTS Foreword ..»•• ......••••••..... v Chapter 1 IntoDduction .•*. 1 Chapter 2 Topography, Indian Trails and the Tide of inmigration . * • . • 6 Ghs^ter 3 Governor Dinwiddle suiid the Assembly •• 15 Chapter 4 Washington's Part in the French and Indian War 39 Chapter 5 She Closing Years of the 'uor ..••• .....86 Chapter 6 The Forts on the Frontier 93 Appendix I» Descriptive List of Frontier Forts 196 Ajopendix II» Illustrative Docvirnents 145 List of Maps 178 Bibliography 179 Vita 207 ************* *** * ill FOREWORD The existing material for a study of the Virginia Frontier during the French and Indian V/ar is relatively accessible. The printed sources are of course familiar to the average student. IThese include the provincial records of the several colonies, particularly Massachusetts, Kew York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. i'hey are to be found in every import- ant library in the country. In Virginia we have the Journals of the House of Burgesses, the Council records, the colonial laws, the Augusta County records, vestry records, newspaper files, the papers and writings of Washington, letters to Washington, and miscellaneous data in numerous county histories, the Calen- dar of Virginia State Papers, the Dinwiddle Papers, the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, and other minor historical publications.