Mapping the Funding Landscape for Biodiversity Conservation in Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Destinations Gihan Tubbeh Renzo Giraldo Renzo Gihan Tubbeh Gihan Tubbeh

7/15/13 8:18 PM 8:18 7/15/13 1 Sur.indd EN_07_Infografia As you head south, you start to see more of Peru’s many different facets; in terms of our ancient cultural legacy, the most striking examples are the grand ruins Ancient Traditions Ancient History Abundant Nature There are plenty of southern villages that still Heading south, you are going to find vestiges of Machu Picchu and road system left by the Incan Empire and the mysterious Nasca Lines. As keep their ancestors’ life styles and traditions Uros Island some of Peru’s most important Pre-Colombian Peru possesses eighty-four of the existing 104 life zones for natural seings, our protected areas and coastal, mountain, and jungle alive. For example, in the area around Lake civilizations. Titicaca, Puno, the Pukara thrived from 1800 Also, it is the first habitat in the world for buerfly, fish and orchid species, second in bird species, and B.C. to 400 A.D., and their decline opened up landscapes offer plenty of chances to reconnect with nature, even while engaging Ica is where you find the Nasca Lines, geoglyphs third in mammal and amphibian species. the development of important cultures like of geometric figures and shapes of animals and in adventure sports in deserts (dunes), beaches, and rivers. And contemporary life the Tiahuanaco and Uro. From 1100 A.D. to the plants on the desert floor that were made 1500 arrival of the Spanish, the Aymara controlled is found in our main cities with their range of excellent hospitality services offered years ago by the Nasca people. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Project Appraisal Document (For CEO Endorsement)

THE WORLD BANK/IFC/M.I.G.A. OFFICE MEMORANDUM DATE: December 19, 2000 TO: Mr. Mohamed El-Ashry, CEO/Chairman, GEF FROM: Lars Vidaeus, GEF Executive Coordinator EXTENSION: 34188 SUBJECT: Peru – Indigenous Management of Natural Protected Areas in the Peruvian Amazon Final GEF CEO Endorsement 1. Please find attached the electronic file of the Project Appraisal Document (PAD) for the above-mentioned project for review prior to circulation Council and your final endorsement. This project was approved for Work Program entry at the May 1999 Council meeting under streamlined Council review procedures. 2. The PAD is fully consistent with the objectives and content of the proposal endorsed by Council as part of the May 1999 Work Program. Minor changes regarding implementation emphasis, clustering of components, and financing plan have been introduced during final project preparation and appraisal. Information on these minor modifications, and how GEFSEC, STAP and Council comments received at Work Program entry have been addressed, are outlined below. Implementation Emphasis 3. As conceived at the time of Work Program entry, the project was going to support the creation and management of four new protected areas (Santiago-Comaina, Gueppi and Alto Purus, El Sira) with the participation of indigenous organizations. A fifth area, Pacaya- Samiria, had already been created as a National Reserve, and was to receive project support for improved management, as part of the Government’s effort to place 10% of the Peruvian Amazon under protection. Following Council approval of the Project Brief in May 1999, GOP demonstrated its commitment to project objectives by establishing three new Reserved Zones (Santiago-Comaina, Gueppi and Alto Purus), surpassing the 10% target. -

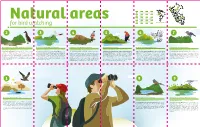

For Bird Watching Areas Additional Information South America

2 9 7 3 4 NPA - Natural Protected Area Peru Habitat 5 6 Best time for birdwatching 1 8 Naturalfor bird watching areas Additional information South America 2 3 4 5 6 7 Los Manglares de Tumbes National Sanctuary Pacaya Samiria National Reserve Pomac Forest Historic Sanctuary Manu National Park Tambopata National Reserve Alto Mayo Protected Forest Bare-throated tiger heron Tigrisoma mexicanum Jabiru Jabiru mycteria Peruvian plantcuer Phytotoma raimondii Andean cock-of-the-rock Rupicola peruvianus Harpy eagle Harpia harpyja Ash-throated antwren Herpsilochmus parkeri Very close to the city of Tumbes, on the northern border of Peru, you will find As the water level starts to decrease in the Amazon lowlands, you will The adventure begins with a visit to the carob trees in the Pomac On the Manu road, between Acjanaco and Tono, and near the famous After a boat trip from Puerto Maldonado and a walk through the Located north of the Alto Mayo rainforest, in an area known as an environment surrounded by mangroves; tall and leafy trees that have given be able to see a great variety of mollusks, amphibians, and birds. The forest. In this 5887-hectare equatorial dry forest you will find a huge Tres Cruces Viewpoint, you will find one of the most famous members of jungle, you will reach a captivating territory with a wealth of flora and Chuquillantas or La Llantería, a mountain ridge can be found. This area the place its name: Los Manglares de Tumbes National Sanctuary. You will visit Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, with a surface area of 2,080,000 carob tree of more than 500 years old, to which the locals aribute the cotingo family: the Andean cock-of-the-rock, which is one of the fauna species. -

A Reappraisal of Phylogenetic Relationships Among Auchenipterid Catfishes of the Subfamily Centromochlinae and Diagnosis of Its Genera (Teleostei: Siluriformes)

ISSN 0097-3157 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES OF PHILADELPHIA 167: 85-146 2020 A reappraisal of phylogenetic relationships among auchenipterid catfishes of the subfamily Centromochlinae and diagnosis of its genera (Teleostei: Siluriformes) LUISA MARIA SARMENTO-SOARES Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, Campus de Goiabeiras, 29043-900, Vitória, ES, Brasil. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8621-1794 Laboratório de Ictiologia, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana. Av. Transnordestina s/no., Novo Horizonte, 44036-900, Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil Instituto Nossos Riachos, INR, Estrada de Itacoatiara, 356 c4, 24348-095, Niterói, RJ. www.nossosriachos.net E-mail: [email protected] RONALDO FERNANDO MARTINS-PINHEIRO Instituto Nossos Riachos, INR, Estrada de Itacoatiara, 356 c4, 24348-095, Niterói, RJ. www.nossosriachos.net E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—A hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships is presented for species of the South American catfish subfamily Centromochlinae (Auchenipteridae) based on parsimony analysis of 133 morphological characters in 47 potential ingroup taxa and one outgroup taxon. Of the 48 species previously considered valid in the subfamily, only one, Centromochlus steindachneri, was not evaluated in the present study. The phylogenetic analysis generated two most parsimonious trees, each with 202 steps, that support the monophyly of Centromochlinae composed of five valid genera: Glanidium, Gephyromochlus, Gelanoglanis, Centromochlus and Tatia. Although those five genera form a clade sister to the monotypic Pseudotatia, we exclude Pseudotatia from Centromochlinae. The parsimony analysis placed Glanidium (six species) as the sister group to all other species of Centromochlinae. Gephyromochlus contained a single species, Gephyromochlus leopardus, that is sister to the clade Gelanoglanis (five species) + Centromochlus (eight species). -

Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon Christian Calienes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 CHRISTIAN CALIENES All Rights Reserved ii The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon by Christian Calienes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Inés Miyares Chair of Examining Committee Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Inés Miyares Thomas Angotti Mark Ungar THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes Advisor: Inés Miyares The resistance movement that resulted in the Baguazo in the northern Peruvian Amazon in 2009 was the culmination of a series of social, economic, political and spatial processes that reflected the Peruvian nation’s engagement with global capitalism and democratic consolidation after decades of crippling instability and chaos. -

Seeds and Plants Imported

y ... - Issued July 26, 191$ U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. WILLIAM A. TAYLOR, Chief of Bureau. INVENTORY OF SEEDS AND PLANTS IMPORTED BY THE OFFICE OF FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION DURING THE PERIOD FROM JULY 1 TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1915. (No. 44; Nos. 4089G TO 41314.) "WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1918. Issued July 26,1918. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. WILLIAM A. TAYLOR, Chief of Bureau. INVENTORY OF SEEDS AND PLANTS IMPORTED OFFICE OF FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION DURING THE PERIOD FROM JULY 1 TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1915. (No. 44; Nos. 40896 TO 41314.) WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1918. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. Chief of Bureau, WILLIAM A. TAYLOR. Associate Chief of Bureau, KARL P. KELLBRMAN. Officer in Charge of Publications, J. E. ROCKWELL, Chief Clerk, JAMES E. JONES. FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION. SCIENTIFIC STAPF. David Fairchild, Agricultural Explorer in Charge, P. H. Dorsett, Plant Introducer, in Charge of Plant Introduction Field Stations. B. T. Galloway, Plant Pathologist, in Charge of Plant Protection and Plant Propagation. Peter Bisset, Plant Introducer, in Charge of Foreign Plant Distribution. Frank N. Meyer, Wilson Popenoe, and F. C. Reimer, Agricultural Explorers. H. C. Skeels, S. C. Stuntz, and R. A. Young, Botanical Assistants. Henry E. Allanson, D. A. Bisset, R. N. Jones, P. G. Russell, and G. P. Van Eseltine, Scientific Assistants. Robert L. Beagles, Superintendent, Plant Introduction Field Station, Chico, Cal. E. O. Orpet, Assistant in Plant Introduction. Edward Simmonds, Superintendent, Plant Introduction Field Station, Miami, Fla. John M. Rankin, Superintendent, Yarrow Plant Introduction Field Station, Rockville, Md. -

CBD First National Report

BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN PERU __________________________________________________________ LIMA-PERU NATIONAL REPORT December 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................ 6 1 PROPOSED PROGRESS REPORT MATRIX............................................... 20 I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................... 29 II BACKGROUND.......................................................................................... 31 a Status and trends of knowledge, conservation and use of biodiversity. ..................................................................................................... 31 b. Direct (proximal) and indirect (ultimate) threats to biodiversity and its management ......................................................................................... 36 c. The value of diversity in terms of conservation and sustainable use.................................................................................................................... 47 d. Legal & political framework for the conservation and use of biodiversity ...................................................................................................... 51 e. Institutional responsibilities and capacities................................................. 58 III NATIONAL GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ON THE CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE USE OF BIODIVERSITY.............................................................................................. 77 -

Fire Probability in South American Protected Areas

Technical Note Fire probability in South American Protected Areas August to October 2020 South American authors: Liana O. Anderson, João B. C. dos Reis, Ana Carolina M. Pessôa, Galia Selaya, Luiz Aragão UK authors: Chantelle Burton, Philip Bett, Chris Jones, Karina Williams, Inika Taylor, Andrew Wiltshire August 2020 1 HOW TO CITE THIS WORK ANDERSON Liana O.; BURTON Chantelle; DOS REIS João B. C.; PESSÔA Ana C. M.; SELAYA Galia; BETT Philip, JONES Chris, WILLIAMS Karina; TAYLOR Inika; WILTSHIRE, Andrew, ARAGÃO Luiz. Fire probability in South American Protected Areas: August to October 2020. 16p. São José dos Campos, 2020.SEI/Cemaden process: 01250.029118/2018-78/5761326. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.13727.79523 Contact: [email protected] Institutions Met Office Hadley Centre – United Kingdom Centro Nacional de Monitoramento e Alerta de Desastres Naturais - Brazil Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais – Brazil This Technical Note was prepared with the support of the following projects: CSSP-BRAZIL - Climate Science for Service Partnership (CSSP) Brazil. Fund: Newton Fund MAP-FIRE – Multi-Actor Adaptation Plan to cope with Forests under Increasing Risk of Extensive fires Fund: Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research (IAI-SGP-HW 016) PRODIGY BMBF biotip Project – Process‐based & Resilience‐Oriented management of Diversity Generates sustainabilitY Fund: German BMBF biotip Project FKZ 01LC1824A João B. C. dos Reis and Ana C. M. Pessôa were funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq - 444321/2018-7 and 140977/2018-5, respectively). Luiz Aragão was funded by CNPq Productivity fellowship (305054/2016-3). Liana Anderson acknowledges EasyTelling, and the projects: CNPq (ACRE-QUEIMADAS 442650/2018-3, SEM-FLAMA 441949/2018-5), São Paulo Research Foundation – (FAPESP 19/05440-5, 2016/02018-2). -

International Tropical Timber Organization

INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER ORGANIZATION ITTO PROJECT PROPOSAL TITLE: STRENGTHENING MANGROVE ECOSYSTEM CONSERVATION IN THE BIOSPHERE RESERVE OF NORTHWESTERN PERU SERIAL NUMBER: PD 601/11 Rev.3 (F) COMMITTEE: REFORESTATION AND FOREST MANAGEMENT SUBMITTED BY: GOVERNMENT OF PERU ORIGINAL LANGUAGE: SPANISH SUMMARY The key problem to be addressed is the “insufficient number of participatory mechanisms for the conservation of mangrove forest ecosystems in the Piura and Tumbes regions (northern Peru)”. Its main causes are: (i) Limited use of legal powers by regional and local governments for the conservation of mangrove ecosystems; ii) low level of forest management and administration for the conservation of mangrove ecosystems; and (iii) limited development of financial sustainability strategies for mangrove forests. These problems in turn lead to low living standards for the communities living in mangrove ecosystem areas and to the loss of biodiversity. In order to address this situation, the specific objective of this project is to “increase the number of participatory mechanisms for mangrove forest protection and conservation in the regions of Tumbes and Piura” with the development objective of “contributing to improving the standard of living of the population in mangrove ecosystem areas in the regions of Tumbes and Piura, Northwest Peru”. In order to achieve these objectives, the following outputs are proposed: 1) Adequate use of legal powers by regional and local governments for the conservation of mangrove forests; 2) Improved level -

Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru. Sippo.Ch Welcome

Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru. sippo.ch Welcome. The Andes, which originate in Patagonia and extend over seven thousand kilometers in South America, have shaped a variety of landscapes, peoples and cultures. Amidst the Andes, Peru is the repository of immeasurable wealth, both tangible and intangible. Icons and “Unique Selling Positions” are Machu Picchu and the mystical city of Cusco, the birthplace of the Inca Empire. But the country offers a lot more to visitors. Our vision is to expand tourism destinations in Peru beyond Machu Picchu to give greater value to the country‘s rich cultural heritage, its abundant biodiversity and world-class gastronomy. The State Secretary for Economic Affairs SECO has been sup- porting sustainable tourism in Peru since 2003, together with two strategic Swiss partners. In cooperation with Swisscontact, SECO promotes the concept of Destination Management Organi- sations (DMOs), which represents a dynamic platform where public and private actors jointly position their regional tourist des- tinations in the international market. This project has led to the establishment of six DMOs in Southern Peru as well as one covering the north of the country. SECO is also financing the Swiss Import Promotion Programme SIPPO which assists leading SMEs with a clear focus on quality and sustainability in their efforts to market their touristic offers internationally. The Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru is a useful milestone in these efforts, providing Swiss tourism business partners and consumers with suitable products in Peru. I wish all readers of the Branch Overview a successful reading and Disclaimer can promise them that SECO will continue to work towards the The information provided in this publication is believed to be ac- growth of tourism in Peru for the benefit of both the Peruvian and curate at the time of writing. -

Natural World Heritage in Latin America and the Caribbean

Natural World Heritage in Latin America and the Caribbean Options to promote an Underutilized Conservation Instrument An independent review prepared for IUCN Tilman Jaeger, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................. iii 1. Background............................................................................................................... 1 2. Approach, objectives and structure ........................................................................... 1 3. Results ...................................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Natural World Heritage in the Region: Numbers and Patterns ............................. 2 3.2 Conceptual Considerations and Perceived Bottlenecks ....................................... 5 4. Conclusions and Recommendations for IUCN .......................................................... 7 4.1 More meaningful involvement of the regional and sub-regional nature conservation communities in formal World Heritage processes ................................. 7 4.2 Refining the "Global Biodiversity Gap Analysis" and "Upstream Support" ............ 8 4.3 Re-visiting existing properties .............................................................................. 9 4.4 Regional networking and capacity development ................................................ 11 4.5 Communication, Education and Awareness-Raising ......................................... 12