Bruce Winstein 1943–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second-Order Correction to the Energy and Momentum in Plane Symmetric Gravitational Waves Like Spacetimes

S S symmetry Article The Second-Order Correction to the Energy and Momentum in Plane Symmetric Gravitational Waves Like Spacetimes Mutahir Ali *, Farhad Ali , Abdus Saboor, M. Saad Ghafar and Amir Sultan Khan Department of Mathematics, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat 26000, Pakistan; [email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (M.S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 December 2018; Accepted: 22 January 2019; Published: 13 February 2019 Abstract: This research provides second-order approximate Noether symmetries of geodetic Lagrangian of time-conformal plane symmetric spacetime. A time-conformal factor is of the form ee f (t) which perturbs the plane symmetric static spacetime, where e is small a positive parameter that produces perturbation in the spacetime. By considering the perturbation up to second-order in e in plane symmetric spacetime, we find the second order approximate Noether symmetries for the corresponding Lagrangian. Using Noether theorem, the corresponding second order approximate conservation laws are investigated for plane symmetric gravitational waves like spacetimes. This technique tells about the energy content of the gravitational waves. Keywords: Einstein field equations; time conformal spacetime; approximate conservation of energy 1. Introduction Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time produced by some of the most violent and energetic processes like colliding black holes or closely orbiting black holes and neutron stars (binary pulsars). These waves travel with the speed of light and depend on their sources [1–5]. The study of these waves provide us useful information about their sources (black holes and neutron stars). -

Uchicago Careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math

UCHICAGOOPPORTUNITIES UChicago Careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math UChicago Careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (UCISTEM) helps students explore, prepare for, and obtain careers or professional school placement in these fields. Students of any major may join UCISTEM, where they have the opportunity to participate in an elective workshop curriculum, in addition to experiential learning options such as research assistantships, internships, externships, and innovation competitions. Opportunities for mentorship, alumni networking, and one-on-one advising are readily available as well. UCISTEM students have gone on to successful careers in a variety of fields, including alternative energy, biotechnology, entrepreneurship, and national laboratory research. Engineering at UChicago UChicago students have the opportunity to engage in engineering through internships, research opportunities, and academic coursework with leading scholars. The University’s Institute for Molecular Engineering is pioneering new undergraduate opportunities in molecular engineering, an emerging field that uses the advances of physics, biology, chemistry, and computation to develop new technologies that can address some of society’s most challenging problems. Students will be trained in a new approach to engineering research and education that researchers anticipate will be applied to clinical medicine, energy supply, clean water production, and quantum computing. As the Advising Institute grows, the faculty plans to develop new coursework, giving students UCISTEM offers students the opportunity to meet with an unparalleled access to new developments and discoveries within engineering. adviser as many times as needed to discuss potential career and academic paths and to ensure students are obtaining skill sets and experiences to successfully pursue those paths. “We’re really trying to do something that transcends traditional Frequent advising topics include resume and application engineering disciplines. -

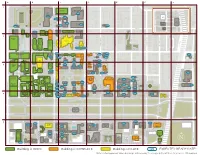

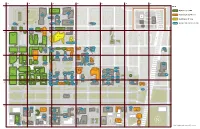

Building Is OPEN Building Is COMPLETE Building Is IN-USE

A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S KIMBARK AVE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer Collegium- TBD - Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - TBD - Integrative Science Physics Hitchcock Hall Cobb Zoology Hutchinson Quadrangle - TBD - Gate Club Institute of- PoliticsTBD - Snell -

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

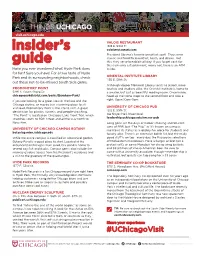

Insider's Guide

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

Science & ROGER PENROSE

Science & ROGER PENROSE Live Webinar - hosted by the Center for Consciousness Studies August 3 – 6, 2021 9:00 am – 12:30 pm (MST-Arizona) each day 4 Online Live Sessions DAY 1 Tuesday August 3, 2021 9:00 am to 12:30 pm MST-Arizona Overview / Black Holes SIR ROGER PENROSE (Nobel Laureate) Oxford University, UK Tuesday August 3, 2021 9:00 am – 10:30 am MST-Arizona Roger Penrose was born, August 8, 1931 in Colchester Essex UK. He earned a 1st class mathematics degree at University College London; a PhD at Cambridge UK, and became assistant lecturer, Bedford College London, Research Fellow St John’s College, Cambridge (now Honorary Fellow), a post-doc at King’s College London, NATO Fellow at Princeton, Syracuse, and Cornell Universities, USA. He also served a 1-year appointment at University of Texas, became a Reader then full Professor at Birkbeck College, London, and Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics, Oxford University (during which he served several 1/2-year periods as Mathematics Professor at Rice University, Houston, Texas). He is now Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor, Fellow, Wadham College, Oxford (now Emeritus Fellow). He has received many awards and honorary degrees, including knighthood, Fellow of the Royal Society and of the US National Academy of Sciences, the De Morgan Medal of London Mathematical Society, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society, the Wolf Prize in mathematics (shared with Stephen Hawking), the Pomeranchuk Prize (Moscow), and one half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics, the other half shared by Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez. -

Rainer Weiss, Professor of Physics Emeritus and 2017 Nobel Laureate

Giving to the Department of Physics by Erin McGrath RAINER WEISS ’55, PHD ’62 Bryce Vickmark Rai Weiss has established a fellowship in the Physics Department because he is eternally grateful to his advisor, the late Jerrold Zacharias, for all that he did for Rai, so he knows firsthand the importance of supporting graduate students. Rainer Weiss, Professor of Physics Emeritus and 2017 Nobel Laureate. Rainer “Rai” Weiss was born in Berlin, Germany in 1932. His father was a physician and his mother was an actress. His family was forced out of Germany by the Nazis since his father was Jewish and a Communist. Rai, his mother and father fled to Prague, Czecho- slovakia. In 1937 a sister was born in Prague. In 1938, after Chamberlain appeased Hitler by effectively giving him Czechoslovakia, the family was able to obtain visas to enter the United States through the Stix Family in St. Louis, who were giving bond to professional Jewish emigrants. When Rai was 21 years-old, he visited Mrs. Stix and thanked her for what she had done for his family. The family immigrated to New York City. Rai’s father had a hard time passing the medi- cal boards because of his inability to answer multiple choice exams. His mother, who Rai says “held the family together,” worked in a number of retail stores. Through the services of an immigrant relief organization Rai received a scholarship to attend the prestigious Columbia Grammar School. At the end of 1945, when Rai was 13 years old, he became fascinated with electronics and music. -

Visitor Map Henry Crown Smart Field House Museum HCFH Alumni Young DASM House Laboratory for Y Astrophysics and E

E. 55TH E. 55TH V Campus North O Campus Residential Commons Stagg Field RECOMMENDEDRatner North Athletics Parking THE UNIVERSITY CenterPARKING Baker Dining RAC Oces Commons C SF OF CHICAGO Court CT Cochrane- Theatre Woods North Field M CWAC Q Visitor Map Henry Crown Smart Field House Museum HCFH Alumni Young DASM House Laboratory for Y Astrophysics and E. 56TH Space Research E. 56TH West High Research Max Palevsky Max Palevsky PRC Max Palevsky Campus Buildings and Dining Campus LASR Energy Institutes Commons Commons (Central) Commons (East) Utility Plant Physics RI (West) WCUP CDD AAC HEP Campus Bookstore / Starbucks Child Temp CAMPUS NORTH A. Devel. – AAC Drexel N B. Co-Op Bookstore / Plein Air Cafe New H Regenstein Hospital Eckhardt Library Parking JFK Research Court Theatre (Future) JRL C. Center KCBD (Open Mansueto Bartlett 2014) Library Dining Commons DBSLC WERC ML D. Harper Memorial Library BC S. INGLESIDE S. DREXEL S. COTTAGE GROVE GROVE S. COTTAGE S. MARYLAND S. ELLIS S. UNIVERSITY S. WOODLAWN S. KIMBARK E. Ida Noyes Hall DBSLC Biopsychological Research BPS Bus 4 E. 57TH T E. 57TH F. Main Quad Collegium Snell-Hitc Anatomy Zoology Hutchinson Mitchell Quadrangle NFC CCD KPTC A Z Logan Center for the Arts hcock Commons Tower Club Q Institute of Politics G. GCIS SH I HC MT IP OMSA Paulson Institute Erman Reynolds PI Mansueto Library Biology Club H. Hillel Culver Center RC 5720 CU EB Stevanovich Botany Pond JCL Mandel STEV Center I. MH Gender Human CAMPUS WEST Searle Lab Studies 5733 Devel. HD DCAM SCL HGS Calvert Human Swift Hall / Grounds of Being Cafe CCH HD J. -

MATTERS of GRAVITY, a Newsletter for the Gravity Community, Number 4

MATTERS OF GRAVITY Number 4 Fall 1994 Table of Contents Editorial ................................................... ................... 2 Correspondents ................................................... ............ 2 Gravity news: Report on the APS Topical Group in Gravitation, Beverly Berger ............. 3 Research briefs: Gravitational Microlensing and the Search for Dark Matter: A Personal View, Bohdan Paczynski .......................................... 5 Laboratory Gravity: The G Mystery and Intrinsic Spin Experiments, Riley Newman ............................... 11 LIGO Project update, Stan Whitcomb ....................................... 15 Conference Reports: PASCOS ’94, Peter Saulson .................................................. 16 The Vienna meeting, P. Aichelburg, R. Beig .................................. 19 The Pitt Binary Black Hole Grand Challenge Meeting, Jeff Winicour ......... 20 International Symposium on Experimental Gravitation, Nathiagali, Pakistan, Munawar Karim ....................................... 22 arXiv:gr-qc/9409004v1 2 Sep 1994 10th Pacific Coast Gravity Meeting , Jim Isenberg ........................... 23 Editor: Jorge Pullin Center for Gravitational Physics and Geometry The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802-6300 Fax: (814)863-9608 Phone (814)863-9597 Internet: [email protected] 1 Editorial The newsletter strides on. I had to perform some pushing around and arm-twisting to get articles for this number. I wish to remind everyone that suggestions and ideas for contributions are especially welcome. The newsletter is growing rather weak on the theoretical side. Keep those suggestions coming! I put together this newsletter mostly on a palmtop computer while travelling, with some contributions arriving the very day of publication (on which, to complicate matters, I was giving a talk at a conference, my email reader crashed and our network went down). One of the contributions is a bit longer than the usual format. Again it is my fault for failing to warn the author in due time. -

Gravitational Waves WARNING!!!!

Gravitational Waves WARNING!!!! ⚫ Terminology is treacherous! ⚫ There are gravitational waves (our topic) and there are gravity waves (a topic for a surfing class). Mix them to your peril. Gravitational waves ⚫ Movie The History ⚫ The history of gravitational waves is rocky. Einstein argued in 1916 that gravitational waves must exist – if the space-time is dynamic, there must be ripples on it. ⚫ Einstein derived the approximate formula for the gravitational waves from two orbiting bodies. ⚫ In 1922 Eddington (that one) argued that gravitational waves were not real and just a mathematical artefact. The History ⚫ In 1936 Einstein wrote a paper with Nathan Rosen reversing his original view; they concluded that all gravitational waves should collapse into black holes. ⚫ The paper was submitted to Physics Review but was returned after the referee pointed out a mistake in it. ⚫ Einstein got berserk in response, writing an angry letter to the editor and promising never to publish in Physics Review again. The History ⚫ Einstein was later persuaded by Infeld of his mistake and corrected the paper. Rosen never conceded. ⚫ In 1957 Richard Feymann (a very famous particle physicist) presented a “sticky bead” argument that convinced most people that gravitational waves are real. The Challenge ⚫ The primary challenge with gravitational waves is that in GR there is no (unambiguous) mathematical expression for its energy. ⚫ Since locally space-time is Minkowski, in the local inertial reference frame the energy of gravitational waves is zero. I.e., that energy is non-local, one cannot claim that the energy of gravitational waves is … at his location, only that the total energy is such and such. -

Highlights of Modern Physics and Astrophysics

Highlights of Modern Physics and Astrophysics How to find the “Top Ten” in Physics & Astrophysics? - List of Nobel Laureates in Physics - Other prizes? Templeton prize, … - Top Citation Rankings of Publication Search Engines - Science News … - ... Nobel Laureates in Physics Year Names Achievement 2020 Sir Roger Penrose "for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity" Reinhard Genzel, Andrea Ghez "for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy" 2019 James Peebles "for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology" Michel Mayor, Didier Queloz "for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star" 2018 Arthur Ashkin "for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics", in particular "for the optical tweezers and their application to Gerard Mourou, Donna Strickland biological systems" "for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics", in particular "for their method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses" Nobel Laureates in Physics Year Names Achievement 2017 Rainer Weiss "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the Kip Thorne, Barry Barish observation of gravitational waves" 2016 David J. Thouless, "for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions F. Duncan M. Haldane, and topological phases of matter" John M. Kosterlitz 2015 Takaaki Kajita, "for the discovery of neutrino oscillations, which shows that Arthur B. MsDonald neutrinos have mass" 2014 Isamu Akasaki, "for the invention of -

RSO Guidelines & Policies

Recognized Student Organizations (RSOs): Guidelines & Policies (2/2020 – Effective July 1, 2021) Reservation Policies • The Student Centers schedules and manages events in Ida Noyes Hall, the Reynolds Club, Bartlett Hall (first floor), Mandel Hall, Harper/Stuart Classrooms (evenings and weekends), and the Quads. • Requests for space can be submitted online using Virtual EMS at http://reserve.uchicago.edu. Inquiries regarding availability can be made by clicking the “Browse for Space” option. You may also call us 773-834-0858 or email us at [email protected]. • Space requests are accepted up to one year in advance, but only one request for space for a future quarter may be processed prior to the room lottery for that quarter. Standing or repeating reservations are only permitted through the room lottery and for venues covered by the room lottery. Requests outside of this policy are considered on a case-by-case basis and are not guaranteed. • The room lottery is held during the 8th week of each quarter except for summer, unless otherwise noted. Further information on the room lottery may be found at https://eventservices.uchicago.edu/page/room-lottery. • We require advance notice to schedule, approve, and plan your events: o Reservation requests for meetings or small events should be submitted at least (2) business days in advance of the desired date. o Reservation requests for large-scale events and outdoor space should be submitted at least (7) business days in advance of the desired date. o Reservation requests for food service spaces (Hallowed Grounds or Hutchinson Commons during dining hours) require additional approvals and should be submitted at least (14) business days in advance of the desired date.