Tilburg University Vengeance Elshout, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leftist Case for War in Iraq •fi William Shawcross, Allies

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 27, Issue 6 2003 Article 6 Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard Abstract Shawcross is superbly equipped to assess the impact of rogue States and terrorist organizations on global security. He is also well placed to comment on the risks of preemptive invasion for existing alliances and the future prospects for the international rule of law. An analysis of the ways in which the international community has “confronted evil,” Shawcross’ brief polemic argues that U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were right to go to war without UN clearance, and that the hypocrisy of Jacques Chirac was largely responsible for the collapse of international consensus over the war. His curious identification with Bush and his neoconservative allies as the most qualified to implement this humanitarian agenda, however, fails to recognize essential differences between the leftist case for war and the hard-line justification for regime change in Iraq. BOOK REVIEW VENGEANCE AND EMPIRE: THE LEFTIST CASE FOR WAR IN IRAQ WILLIAM SHAWCROSS, ALLIES: THE U.S., BRITAIN, EUROPE, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ* Hal Blanchard** INTRODUCTION In early 2002, as the war in Afghanistan came to an end and a new interim government took power in Kabul,1 Vice President Richard Cheney was discussing with President George W. -

Martha L. Minow

Martha L. Minow 1525 Massachusetts Avenue Griswold 407, Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-4276 [email protected] Current Academic Appointments: 300th Anniversary University Professor, Harvard University Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor Faculty, Harvard Graduate School of Education Faculty Associate, Carr Center for Human Rights, Harvard Kennedy School of Government Current Activities: Advantage Testing Foundation, Vice-Chair and Trustee American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Access to Justice Project American Bar Association Center for Innovation, Advisory Council American Law Institute, Member Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University, Director Campaign Legal Center, Board of Trustees Carnegie Corporation, Board of Trustees Committee to Visit the Harvard Business School, Harvard University Board of Overseers Facing History and Ourselves, Board of Scholars Harvard Data Science Review, Associate Editor Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Law, Violence, and Meaning Series, Univ. of Michigan Press, Co-Editor MacArthur Foundation, Director MIT Media Lab, Advisory Council MIT Schwarzman College of Computing, Co-Chair, External Advisory Council National Academy of Sciences' Committee on Science, Technology, and Law Profiles in Courage Award Selection Committee, JFK Library, Chair Russell Sage Foundation, Trustee Skadden Fellowship Foundation, Selection Trustee Susan Crown Exchange Foundation, Trustee WGBH Board of Trustees, Trustee Education: Yale Law School, J.D. 1979 Articles and Book Review Editor, Yale Law Journal, 1978-1979 Editor, Yale Law Journal, 1977-1978 Harvard Graduate School of Education, Ed.M. 1976 University of Michigan, A.B. 1975 Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude James B. Angell Scholar, Branstrom Prize New Trier East High School, Winnetka, Illinois, 1968-1972 Honors and Fellowships: Leo Baeck Medal, Nov. -

Operation Vengeance Still Offering Lessons After 75 Years

Operation Vengeance Still Offering Lessons after 75 Years Lt Col Scott C. Martin, USAF Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in theAir & Space Power Journal (ASPJ) are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be repro duced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the ASPJ requests a courtesy line. he spring of 2018 marked the 75th anniversary of the execution of the first high-value individual (HVI)/target of opportunity (TOO) operation by air- power in history. On 18 April 1943, 18 Army Air Corps P-38 Lightning fight Ters took off from an airfield on Henderson Island in the south Pacific Ocean, slated to target Adm Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander of the Japanese Imperial Navy. Based on the successful intercept of the admiral’s itinerary via the codebreakers working at Station HYPO (also known as Fleet Radio Unit Pacific) in Hawaii, the US knew of Yamamoto’s plans to visit the Japanese base at Bougainville Island in Papua, New Guinea. The US fighters, maintaining radio silence and flying low over the ocean to evade Japanese radar, successfully ambushed the two Japanese bomb ers and six escort fighters, shooting down both bombers, one of which held the ad miral. With the loss of only one plane, the US managed to eliminate one of the top military commanders in the Japanese military and score a huge propaganda vic tory. -

'Go and Sin No More': Christian Mercy Vs. Tabloid Vengeance Stuart Dew Describes Some Biblical Examples of Forgiveness Towards Wrongdoers

'Go and Sin No More': Christian mercy vs. tabloid vengeance Stuart Dew describes some biblical examples of forgiveness towards wrongdoers. s I often do when talking in public on behalf and other high profile offenders as evil is comforting, of the Churches' Criminal Justice Forum for, if they are the personification of evil, the rest of A (CCJF), I asked the group of local us are okay. We are normal; we are the good guys. To churchgoers what Christian values they linked with consider that we are all capable of doing both right criminal justice. The first respondent folded his arms and wrong requires us to share ownership for dealing across his chest and said firmly "Punishment for sin". with criminal behaviour. That is a message that It wasn't one of the values at the forefront of my Churches' Criminal Justice Forum tries to put across. mind, and I wondered if this might be a more One of my favourite Bible stories is where a group challenging evening than some. However, it proved of men bring to Christ a woman caught in adultery. to be a good starting point for discussion, and Leaving aside the fact that a man may also have had encouraged others present to think more deeply about some complicity in this offence (for that was the the issues, which is one of our aims. culture of the age), stoning is suggested by the group / asked the group of local churchgoers what Christian values they linked with criminal justice. The first respondent folded his arms across his chest and said firmly "Punishment for sin". -

MEDIA ADVISORY: Thursday, August 11, 2011**

**MEDIA ADVISORY: Thursday, August 11, 2011** WWE SummerSlam Cranks Up the Heat at Participating Cineplex Entertainment Theatres Live, in High-Definition on Sunday, August 14, 2011 WHAT: Three championship titles are up for grabs, one will unify the prestigious WWE Championship this Sunday. Cineplex Entertainment, via our Front Row Centre Events, is pleased to announce WWE SummerSlam will be broadcast live at participating Cineplex theatres across Canada on Sunday, August 14, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. EDT, 7:00 p.m. CDT, 6:00 p.m. MDT and 5:00 p.m. PDT live from the Staples Center in Los Angeles, CA. Matches WWE Champion John Cena vs. WWE Champion CM Punk in an Undisputed WWE Championship Match World Heavyweight Champion Christian vs. Randy Orton in a No Holds Barred Match WWE Divas Champion Kelly Kelly vs. Beth Phoenix WHEN: Sunday, August 14, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. EDT, 7:00 p.m. CDT, 6:00 p.m. MDT and 5:00 p.m. PDT WHERE: Advance tickets are now available at participating theatre box offices, through the Cineplex Mobile Apps and online at www.cineplex.com/events or our mobile site m.cineplex.com. A special rate is available for larger groups of 20 or more. Please contact Cineplex corporate sales at 1-800-313-4461 or via email at [email protected]. The following 2011 WWE events will be shown live at select Cineplex Entertainment theatres: WWE Night of Champions September 18, 2011 WWE Hell in the Cell October 2, 2011 WWE Vengeance (formerly Bragging Rights) October 23, 2011 WWE Survivor Series November 20, 2011 WWE TLC: Tables, Ladders & Chairs December 18, 2011 -30- For more information, photos or interviews, please contact: Pat Marshall, Vice President, Communications and Investor Relations, Cineplex Entertainment, 416-323- 6648, [email protected] Kyle Moffatt, Director, Communications, Cineplex Entertainment, 416-323-6728, [email protected] . -

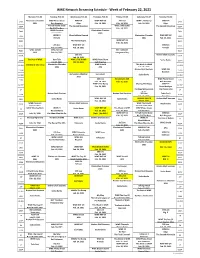

WWE Network Streaming Schedule - Week of February 22, 2021

WWE Network Streaming Schedule - Week of February 22, 2021 Monday, Feb 22 Tuesday, Feb 23 Wednesday, Feb 24 Thursday, Feb 25 Friday, Feb 26 Saturday, Feb 27 Sunday, Feb 28 Elimination Chamber WWE Photo Shoot WWE 24 WWE NXT UK 205 Live WWE's The Bump WWE 24 6AM 6AM 2021 Ron Simmons Edge Feb. 18, 2021 Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 24, 2021 Edge R-Truth Game Show WWE's The Bump 6:30A The Second Mountain The Second Mountain 6:30A Big E & The Boss Feb. 24, 2021 WWE Chronicle Elimination Chamber 7AM 7AM Bianca Belair 2021 WWE 24 WrestleMania Rewind Elimination Chamber WWE NXT UK 7:30A 7:30A R-Truth 2021 Feb. 25, 2021 WWE NXT UK 8AM The Mania Begins 8AM Feb. 25, 2021 205 Live WWE NXT UK WWE 24 8:30A 8:30A Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 18, 2021 R-Truth WWE Untold WWE NXT UK NXT TakeOver 9AM 9AM APA Feb. 18, 2021 Vengeance Day 205 Live Broken Skull Sessions 9:30A 9:30A Feb. 19, 2021 The Best of WWE Raw Talk WWE's THE BUMP WWE Photo Shoot 10AM Sasha Banks 10AM Feb 22, 2021 FEB 24, 2021 Kofi Kingston Elimination Chamber WWE Untold This Week in WWE 10:30A The Best of John Cena 10:30A 2021 APA Feb. 25, 2021 Broken Skull Sessions WWE 365 11AM 11AM Ricochet Elimination Chamber Liv Forever 11:30A Sasha Banks 11:30A 2021 205 Live SmackDown 549 WWE Photo Shoot 12N 12N Feb. 19, 2021 Feb. 26, 2010 Kofi Kingston WWE's The Bump Chasing The Magic WWE 24 12:30P 12:30P Feb. -

Anewplace Toplay

U-14 girls Carole Hester’s ON THE MARKET win Roseville Looking About Guide to local real estate Tournament UDJ column .......................................Inside ..........Page A-8 .............Page A-3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .......Page A-2 Tomorrow: Sunny; near-record heat 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY June 23, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 44 pages, Volume 148 Number 75 email: [email protected] Discussion on ordinance turns testy By KATIE MINTZ whose terms coincide with those of the The Daily Journal UKIAH CITY COUNCIL councilmembers who appointed them. The Ukiah City Council covered a If passed, the ordinance will allow number of topics Wednesday evening at each councilmember to nominate a its regular meeting, some with a tinge of to the City Planning Commission. planning commissioner, but will also testy discussion. Currently, the city has five planning require the council as a whole to ratify Of the most fervent was the council’s commissioners -- Ken Anderson, Kevin the selection by a full vote at a City deliberation regarding the introduction Jennings, James Mulheren, Judy Pruden Council meeting. of an ordinance that would affect how and Michael Whetzel -- who were each planning commissioners are appointed appointed by a council member, and See COUNCIL, Page A-10 ANEW PLACE TO PLAY Ukiah soldier killed in Iraq Orchard Park to open on Saturday The Daily Journal Sgt. Jason Buzzard, 31, of Ukiah, has been reported killed in Iraq. The Department of Defense has not yet made a public announcement although a family member has confirmed his death. -

No Way Out, No Way In: Irregular Migrant Children and Families in the UK Research Report, 2012 ISBN 978-1-907271-01-4

NO WAY OUT, NO WAY IN Irregular migrant children and families in the UK RESEARCH REPORT Nando Sigona and Vanessa Hughes NO WAY OUT, NO WAY IN Irregular migrant children and families in the UK Nando Sigona and Vanessa Hughes RESEARCH REPORT May 2012 i Published by the ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, University of Oxford, 58 Banbury Road, OX2 6QS, Oxford, UK Copyright © Nando Sigona and Vanessa Hughes 2012 First published in May 2012 All rights reserved Front cover image by Vince Haig Designed and printed by the Holywell Press Ltd. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements v About the authors vi Executive summary vii Research aims and methodology vii Key findings vii Implications for public policy ix 1. Introduction 1 Research aims 1 Methodology 2 Profile of interviewees 3 Research Ethics 3 Outline of the report 3 PART ONE: Children in irregular migration: definitions, numbers, and policies 5 2. Irregular migrant children: definitions and numbers 6 Key terms and definitions 6 Counting the uncountable 6 3. Irregular migrant children and public policy: A ‘difficult territory’ 9 Legal and policy framework 9 Right to education 11 Right to health and access to healthcare 11 Routes to regularisation 11 PART TWO: Irregular voices 15 4. Migration routes and strategies 16 Journeys 16 Entry routes to the UK and pathways to irregularity 17 Reasons and expectations from migration 17 Why Britain: choice of destination 17 Summary 18 5. Arrival and settlement 19 Arrival and first impressions 19 Accommodation arrangements and quality of accommodation 19 iii Livelihoods 20 Summary 22 6. -

Pro Wrestling Over -Sell

TTHHEE PPRROO WWRREESSTTLLIINNGG OOVVEERR--SSEELLLL™ a newsletter for those who want more Issue #1 Monthly Pro Wrestling Editorials & Analysis April 2011 For the 27th time... An in-depth look at WrestleMania XXVII Monthly Top of the card Underscore It's that time of year when we anything is responsible for getting Eddie Edwards captures ROH World begin to talk about the forthcoming WrestleMania past one million buys, WrestleMania, an event that is never it's going to be a combination of Tile in a shocker─ the story that makes the short of talking points. We speculate things. Maybe it'll be the appearances title change significant where it will rank on a long, storied list of stars from the Attitude Era of of highs and lows. We wonder what will wrestling mixed in with the newly Shocking, unexpected surprises seem happen on the show itself and gossip established stars that generate the to come few and far between, especially in the about our own ideas and theories. The need to see the pay-per-view. Perhaps year 2011. One of those moments happened on road to WreslteMania 27 has been a that selling point is the man that lit March 19 in the Manhattan Center of New York bumpy one filled with both anticipation the WrestleMania fire, The Rock. City. Eddie Edwards became the fifteenth Ring and discontent, elements that make the ─ So what match should go on of Honor World Champion after defeating April 3 spectacular in Atlanta one of the last? Oddly enough, that's a question Roderick Strong in what was described as an more newsworthy stories of the year. -

British Bulldogs, Behind SIGNATURE MOVE: F5 Rolled Into One Mass of Humanity

MEMBERS: David Heath (formerly known as Gangrel) BRODUS THE BROOD Edge & Christian, Matt & Jeff Hardy B BRITISH CLAY In 1998, a mystical force appeared in World Wrestling B HT: 6’7” WT: 375 lbs. Entertainment. Led by the David Heath, known in FROM: Planet Funk WWE as Gangrel, Edge & Christian BULLDOGS SIGNATURE MOVE: What the Funk? often entered into WWE events rising from underground surrounded by a circle of ames. They 1960 MEMBERS: Davey Boy Smith, Dynamite Kid As the only living, breathing, rompin’, crept to the ring as their leader sipped blood from his - COMBINED WT: 471 lbs. FROM: England stompin’, Funkasaurus in captivity, chalice and spit it out at the crowd. They often Brodus Clay brings a dangerous participated in bizarre rituals, intimidating and combination of domination and funk -69 frightening the weak. 2010 TITLE HISTORY with him each time he enters the ring. WORLD TAG TEAM Defeated Brutus Beefcake & Greg With the beautiful Naomi and Cameron Opponents were viewed as enemies from another CHAMPIONS Valentine on April 7, 1986 dancing at the big man’s side, it’s nearly world and often victims to their bloodbaths, which impossible not to smile when Clay occurred when the lights in the arena went out and a ▲ ▲ Behind the perfect combination of speed and power, the British makes his way to the ring. red light appeared. When the light came back the Bulldogs became one of the most popular tag teams of their time. victim was laying in the ring covered in blood. In early Clay’s opponents, however, have very Originally competing in promotions throughout Canada and Japan, 1999, they joined Undertaker’s Ministry of Darkness. -

Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction Author(s): Seri Irazola, Ph.D., Erin Williamson, Julie Stricker, Emily Niedzwiecki Document No.: 244084 Date Received: November 2013 Award Number: GS-23F-8182H This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Final Report Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction Contract No. GS-23F-8182H September, 2013 Submitted to: National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs U.S. Department of Justice Submitted by: ICF Incorporated 9300 Lee Highway Fairfax, VA 22031 Final Report Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction Contract No. GS-23F-8182H September, 2013 Submitted to: National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs U.S. Department of Justice Submitted by: ICF Incorporated 9300 Lee Highway Fairfax, VA 22031 Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction Study of Victim Experiences of Wrongful Conviction Seri Irazola, Ph.D. Erin Williamson Julie Stricker Emily Niedzwiecki ICF International 9300 Lee Highway Fairfax, VA 22031-1207 This project was supported by Contract No. GS-23F-8182H, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. -

Badal a Culture of Revenge the Impact of Collateral Damage on Taliban Insurgency

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2008-03 Badal a culture of revenge the impact of collateral damage on Taliban insurgency Hussain, Raja G. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4222 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS BADAL: A CULTURE OF REVENGE THE IMPACT OF COLLATERAL DAMAGE ON TALIBAN INSURGENCY by Raja G. Hussain March 2008 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Thesis Co Advisor: Feroz H. Khan Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE BADAL: A Culture of Revenge 5. FUNDING NUMBERS The Impact of Collateral Damage on Taliban Insurgency 6. AUTHOR(S) Raja G. Hussain 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9.