Chapter 1 Charley—Friday: 12:22 H Ours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Court of Appeal of the State of California

Filed 12/7/15 Certified for Publication 12/22/15 (order attached) IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION THREE THE PEOPLE, Plaintiff and Respondent, G050444 v. (Super. Ct. No. 13CF1958) RAPHAEL JARED SCALLY, O P I N I O N Defendant and Appellant. Appeal from a judgment of the Superior Court of Orange County, Michael J. Cassidy, Judge. Affirmed. David R. Greifinger, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant. Kamala D. Harris, Attorney General, Gerald A. Engler, Chief Assistant Attorney General, Julie L. Garland, Assistant Attorney General, Charles C. Ragland and Marvin E. Mizell, Deputy Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent. * * * The jury found defendant guilty of one count of pimping (Pen. Code, § 266h, subd. (a)) and one count of pandering (Pen. Code, § 266i, subd. (a)). The court held a bench trial and found it to be true that defendant committed the offenses while out on bail. (Pen. Code, § 12022.1, subd. (b).) The court sentenced defendant to the midterm of four years on the pimping count, stayed imposition of the sentence on the pandering count, and imposed, but stayed, a two year on-bail enhancement. On appeal, defendant raises a single issue: that the court erred by permitting the People’s expert to testify that certain text messages sent from defendant to individuals other than the particular prostitute at issue were consistent with pimping activity. Defendant contends this was improper character evidence under Evidence Code section 1101. We conclude the evidence was relevant to rebut the defense that the prostitute was merely defendant’s girlfriend — a nonpropensity basis for relevance — and thus we affirm. -

Jeezy All There Mp3 Download

Jeezy all there mp3 download Continue :Gaana Albums English Albums Source:2,source_id:1781965.object_type:2,id:1781965,status:0,title:All there,trackcount:1,track_ids:20634275 Objtype:2,share_url:/album/all-there,album: artist: artist_id:12643, name:Jizi,ar_click_url:/artist/jizi, ArtistAll اﻟﻘﺎﺋﻤﺔ اﻟﺼﻔﺤﺔ اﻟﺮﺋﻴﺴﻴﺔ أﻏﺎﻧﻲ ﺟﺪﻳﺪة اﺗﺼﺎل artist_id:12643,name:Jizi,ar_click_url:/artist/jizi,artist_id:696808, title:Bankroll Fresh, ar_click_url:/artist/bankroll-fresh,premium_content:0.release_date:Oct 08, 2016, 03:18,Language:English - Album Is Inactive All That Is An English Album, released in October 2016. All There Album has one song performed by Jeezy, Bankroll Fresh. Listen to all the songs there in high quality and download all there song on Gaana.com Related Tags - All There, All There Songs Download, Download All There Songs, Listen to All There Songs, All There MP3 Songs, Jeezy Songs Bankroll Fresh All There Free mp3 download and stream. The songs we share are not taken from websites or other media, we don't store mp3 files of new songs on our server, but we take them from YouTube to do so. Jeezy All There Ft Bankroll Fresh mp3 high quality download on MusicEels. Choose from multiple sources of music. A commentary in the genre of hip-hop from Kevin a a A Jerichos Revenge Fight to pull up make sure that yall there comment Simon AKERMAN LIT. Comment by Charles Sanchez 12 R.I.P. MIGUEL VARGAS Comment by Elijah Kramer Automatic I don't need a clue in this Comment Bloody Bird all there ̧x8F ̄ Michael Rainford's comment is all there all ̄ Comment by Curtis Madden and Comment by Chris Smither hot cheeto that I snack on.. -

Flashback, Flash Forward: Re-Covering the Body and Id-Endtity in the Hip-Hop Experience

FLASHBACK, FLASH FORWARD: RE-COVERING THE BODY AND ID-ENDTITY IN THE HIP-HOP EXPERIENCE Submitted By Danicia R. Williams As part of a Tutorial in Cultural Studies and Communications May 04,2004 Chatham College Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Tutor: Dr. Prajna Parasher Reader: Ms. Sandy Sterner Reader: Dr. Robert Cooley ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Prajna Paramita Parasher, my tutor for her faith, patience and encouragement. Thank you for your friendship. Ms. Sandy Sterner for keeping me on my toes with her wit and humor, and Dr. Cooley for agreeing to serve on my board. Kathy Perrone for encouraging me always, seeing things in me I can only hope to fulfill and helping me to develop my writing. Dr. Anissa Wardi, you and Prajna have changed my life every time I attend your classes. My parent s for giving me life and being so encouraging and trusting in me even though they weren't sure what I was up to. My Godparents, Jerry and Sharon for assisting in the opportunity for me to come to Chatham. All of the tutorial students that came before me and all that will follow. I would like to give thanks for Hip-Hop and Sean Carter/Jay-Z, especially for The Black Album. With each revolution of the CD my motivation to complete this project was renewed. Whitney Brady, for your excitement and brainstorming sessions with me. Peace to Divine Culture for his electricity and Nabri Savior. Thank you both for always being around to talk about and live in Hip-Hop. Thanks to my friends, roommates and coworkers that were generally supportive. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Chart: Top25 VIDEO HIP HOP

Chart: Top25_VIDEO_HIP HOP Report Date (TW): 2012-04-15 --- Previous Report Date(LW): 2012-04-08 TW LW TITLE ARTIST GENRE RECORD LABEL 1 1 Ayy Ladies Travis Porter Ft. Tyga Hip Hop RCA Records 2 3 Leave You Alone (explicit) Ft. Ne-yo Young Jeezy Hip Hop Island Records 3 2 Rack City (remix)-ymcmb Tyga Ft. Young Jeezy, Fabolous Meek Mill T.i. And Hip Hop YMCMB 4 4 Spend It (remix) 2 Chainz Ft Ti Hip Hop Def Jam Records 5 5 Freaky Tales (remix) (dirty) Too Short & Snoop Dogg Hip Hop Up All Nite Records 6 7 Round Of Applause Ft. Drake (dirty) Waka Flocka Flame Hip Hop Atlantic Records 7 8 Slight Work Ft. Big Sean (dirty) Wale Hip Hop MayBach Music 8 9 High Definition (dirty) Rick Ross Hip Hop MayBach Music 9 10 I Just Wanna Ft. Tony Yayo (dirty) 50 Cent Hip Hop G Unit Records 10 11 Function Ft. Yg, Problem & Iamsu E-40 Hip Hop SickWidItRecords / BME / Warner 11 6 Drank In My Cup Kirko Bangz Hip Hop Intoxication / Reprise Records 12 17 Im In Love With A White Girl Ft. Yo Gotti Gucci Mane Hip Hop Warner Bros 13 15 Got One (dirty) 2 Chainz Hip Hop Def Jam Records 14 21 So Good B.o.b Hip Hop Atlantic Records 15 18 Nobodys Perfect (explicit) Ft. Missy Elliott J. Cole Hip Hop RCA Records 16 22 Sabotage Ft. Lloyd Wale Hip Hop MayBach Music 17 20 Hard In Da Paint (freestyle) Tyga Hip Hop YMCMB 18 Fast Lane E-40 Hip Hop SickWit it Records / Warner Bros 19 Fuck Da City Up Ft. -

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

LEAVE THEM ALONE (MATTHEW 28:18-20) by Don Krider

LEAVE THEM ALONE (MATTHEW 28:18-20) By Don Krider I want you to turn in your Bible to Matt 28; we are going to look at Jesus' commission. We have added to His commission; we have changed the way in which it operates. We have organized it in our own organization and then wonder why it doesn't work. We wonder why we are wearing ourselves out, and it is because we serve God in the flesh more than we do in the spirit. We work our flesh to death trying to get something done, but He said, "It's not by power nor might but by my spirit, saith the Lord." (Zech 4:6) He said, "It isn't by anything you can do in the physical; it's by total surrender to Me, allowing My spirit to work through you so things will be accomplished." So Jesus, in the closing of His message before He left the earth, said these words: Matt 28:18-19 All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth; go ye therefore.... He didn't say, "Think about it." He didn't say, "Elect a group to go." He said, "GO." I see the word of God as an action word, but it isn't a natural action word; it is a spiritual word. If I am not going in my spirit I can send my body everywhere but it's not going to go anywhere for the Lord. A lot of times we volunteer for this, we volunteer for that, and then we murmur and complain, grumble, and gripe all the time we are doing it. -

The Integration of Contemporary Worship Hymns Into the Church: an Analysis of Contemporary Worship Music Styles and Their Historical Development

The Integration of Contemporary Worship Hymns into the Church: An Analysis of Contemporary Worship Music Styles and Their Historical Development An Honors Thesis (Honors 499) By: William W. Riggs Thesis Advisor Douglas D. Amman Ball State University Muncie, IN December 2000 Expected date of graduation: May 2001 Overview: This project involved the attendance at approximately fifteen different churches to practically observe worship styles. With background historical research, I then wrote a summarizing paper and proceeded in the recording and composition of ten new worship songs. It was done to encourage the integration of contemporary music and eliminate legalistic barriers in traditional church services. Contents: Development of Research: I. Paper Prospectus II. Working Bibliography ill. Formal Honors College Proposal Synthesis: I. Church Visit Summaries II. Historical Summary ill. Synthesis of Research IV. Bibliography Analysis of Recording: I. Track Information II. Process and Means ill. Analysis of Compositions Appendix: I. Church Bulletins II. Influential Articles and Miscellaneous Materials III. CD Development of Research: 1. Paper Prospectus II. Working Bibliography III. Formal Honors College Proposal Billy Riggs - Senior Honors Thesis 28 August 2000 Thesis Prospectus For my Honors thesis, which I am registered for in the fall of 2000, I would like to do a project surrounding the topic of contemporary church music. I want to study the historical progression of more recent contemporary church worship music. This will'involve gaining a foundation of 19th century worship music, but primarily focus on changes that have occurred since the 1970's that have worked to fuse the formerly forbidden sounds of rock and pop into the church. -

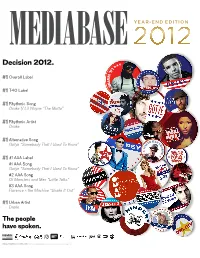

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Message in the Music 5 1

c. …To Messenger Of God i. He is a messenger who just wants to get his message (God’s music) out there! ii. What has he learned most recently? Learned patience… God will get you through anything! iii. Which really is the theme for this song / night iv. His music = 3 albums, songs like: “You Are”, “Love Has Come For Me”, “More Of You”, “Through All Of It”, and “Limitless” v. This is too good not to share… the rest of the interview, getting to know him: Video = Getting To Know Colton Dixon – Part 2 (3:17) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZSDJ1DVpM44 vi. Don’t you just love this guy? Love his heart? vii. Listen to his life verse again… Message in the Music 5 1. John 13:16 = “Very truly I tell you, no First Baptist Student Ministry - Wednesday, July 20, 2016 servant is greater than his master, nor is a messenger greater than the one who sent Here’s someone just like you, a former teenager, who just wants to be used by him.” (NIV) God. Meet Colton Dixon and the message behind one of his greatest songs ever viii. That should remind you that God wants to use your called “Through All Of It”… life, no matter who you are and what you’ve done! I. The Man Known As Colton Dixon II. The Struggles Known As Life a. From Average Teenager… a. We All Struggle! i. Michael Colton Dixon i. That’s a fact… we all face hard times in life ii. Born in 1991 (age 24) in Murfreesboro, TN ii. -

Abstract Humanities Jordan Iii, Augustus W. B.S. Florida

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES JORDAN III, AUGUSTUS W. B.S. FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY, 1994 M.A. CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, 1998 THE IDEOLOGICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: A STUDY OF SELECTED HIP-HOP ARTISTS Advisor: Dr. Viktor Osinubi Dissertation Dated May 2009 This study examined the discourse of selected Hip-Hop artists and the biographical aspects of the works. The study was based on the structuralist theory of Roland Barthes which claims that many times a performer’s life experiences with class struggle are directly reflected in his artistic works. Since rap music is a counter-culture invention which was started by minorities in the South Bronx borough ofNew York over dissatisfaction with their community, it is a cultural phenomenon that fits into the category of economic and political class struggle. The study recorded and interpreted the lyrics of New York artists Shawn Carter (Jay Z), Nasir Jones (Nas), and southern artists Clifford Harris II (T.I.) and Wesley Weston (Lii’ Flip). The artists were selected on the basis of geographical spread and diversity. Although Hip-Hop was again founded in New York City, it has now spread to other parts of the United States and worldwide. The study investigated the biography of the artists to illuminate their struggles with poverty, family dysfunction, aggression, and intimidation. 1 The artists were found to engage in lyrical battles; therefore, their competitive discourses were analyzed in specific Hip-Hop selections to investigate their claims of authorship, imitation, and authenticity, including their use of sexual discourse and artistic rivalry, to gain competitive advantage.