Expanding Apprenticeship a Way to Enhance Skills and Careers Robert I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

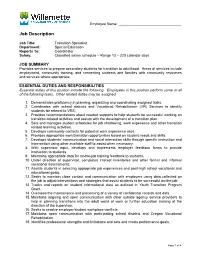

Job Description

Employee Name: Job Description Job Title: Transition Specialist Department: Special Education Reports To: Coordinator Salary: Classified salary schedule – Range 13 – 220 calendar days JOB SUMMARY Provides services to prepare secondary students for transition to adulthood. Areas of services include employment, community training, and connecting students and families with community resources and services where appropriate. ESSENTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Essential duties of this position include the following. Employees in this position perform some or all of the following tasks. Other related duties may be assigned. 1. Demonstrates proficiency in planning, organizing and coordinating assigned tasks. 2. Coordinates with school districts and Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Services to identify students for referral to VRS. 3. Provides recommendations about needed supports to help students be successful working on transition-related activities and assists with the development of a transition plan. 4. Sets and manages student schedules for job shadowing, work experience and other transition related learning activities. 5. Develops community contacts for potential work experience sites. 6. Provides appropriate work/transition opportunities based on student needs and skills. 7. Develops students' communication and social interaction skills through specific instruction and intervention using other available staff to assist when necessary. 8. With supervisor input, develops and implements employer feedback forms to provide instruction to students. 9. Maintains appropriate data for on-the-job training feedback to students. 10. Under direction of supervisor, completes interest inventories and other formal and informal vocational assessments. 11. Assists students in selecting appropriate job experiences and post-high school vocational and educational goals. 12. Seeks to maintain close contact and communication with employers using data collected on the job to adjust interventions and strategies that assist students to be successful on-the-job. -

Further Education in the United States of America

FURTHER EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1. Overview There is no national education system present in the United States. Due to the federal nature of the government, the local and state governments perhaps have a greater deal of control over education. As a result, there is no country-level education system or curriculum. The federal government does not operate public schools. Each state has its own Department of Education. In terms of funding, public schools receive funding from the individual state, and also from local property taxes. Public colleges and universities receive funding from the state in which they reside. Each state's legislative body decides how much funding will be given educational providers within that particular state. Students aged 1-18 do not pay tuition fees, this ends if the student wishes to go to a college or a university where students do pay tuition fees. However, some students receive some sort of funding, either through a scholarship or through a loan. In the United States, education is compulsory for all students until ages sixteen to eighteen depending on the individual state. Most high school students graduate at the age of seventeen or eighteen-years-old. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that 58% of high school graduates enrolled in colleges or universities in 2006. Students have the option of attending a two- year community college (also known as a junior college) before applying to a four-year university. Admission to community college is easier, and class sizes are often smaller than in a university. Community college students can earn an Associate's degree and transfer up to two years of course credits to a university. -

Section 061053 - Miscellaneous Rough Carpentry

SECTION 061053 - MISCELLANEOUS ROUGH CARPENTRY PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 RELATED DOCUMENTS A. Drawings and general provisions of the Contract, including General and Supplementary Conditions and Division 01 Specification Sections, apply to this Section. 1.2 SUMMARY A. This Section includes the following: 1. Wood framing, blocking, and nailers 2. Wood battens, shims, and furring (for wall panel attachment). 3. Plywood sheathing for miscellaneous structures and replacement of deteriorated roof sheathing. B. Related Sections include the following: 1. Section 075216 "SBS Modified Bituminous Membrane Roofing" for adhesively applied 2-ply, SBS bituminous membrane roofing, with self-adhered base ply sheet. 2. Section 076200 "Sheet Metal Flashing and Trim" for installing sheet metal flashing and trim integral with roofing. 1.3 DEFINITIONS A. Dimension Lumber: Lumber of 2-inches nominal or greater but less than 5-inches nominal in least dimension. B. Lumber grading agencies, and the abbreviations used to reference them, include the following: 1. NLGA: National Lumber Grades Authority. 2. WCLIB: West Coast Lumber Inspection Bureau. 3. WWPA: Western Wood Products Association. 1.4 QUALITY ASSURANCE A. Testing Agency Qualifications: For testing agency providing classification marking for fire- retardant treated material, an inspection agency acceptable to authorities having jurisdiction that periodically performs inspections to verify that the material bearing the classification marking is representative of the material tested. PRSD – Thompson Elementary School Roof Replacement 061053 – MISCELLANEOUS ROUGH CARPENTRY July, 2012 Page 1 of 7 B. Forest Certification: For the following wood products, provide materials produced from wood obtained from forests certified by an FSC-accredited certification body to comply with FSC 1.2, "Principles and Criteria": 1. -

The Impact of Further Education Learning

BIS RESEARCH PAPER NUMBER 104 The Impact of Further Education Learning JANUARY 2013 1 The Impact of Further Education Learning The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET www.gov.uk/bis Research paper number 71 January 2013 2 The Impact of Further Education Learning About London Economics London Economics is one of Europe's leading specialist economics and policy consultancies and has its head office in London. We also have offices in Brussels, Dublin, Cardiff and Budapest, and associated offices in Paris and Valletta. We advise clients in both the public and private sectors on economic and financial analysis, policy development and evaluation, business strategy, and regulatory and competition policy. Our consultants are highly-qualified economists with experience in applying a wide variety of analytical techniques to assist our work, including cost-benefit analysis, multi-criteria analysis, policy simulation, scenario building, statistical analysis and mathematical modelling. We are also experienced in using a wide range of data collection techniques including literature reviews, survey questionnaires, interviews and focus groups. Head Office: 71-75 Shelton Street, London, WC2H 9JQ, United Kingdom. w: www.londecon.co.uk e: [email protected] t: +44 (0)20 7866 8185 f: +44 (0)20 7866 8186 The Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute Ipsos MORI's Social Research Institute is the leader in public sector research, helping policy and decision-makers understand what works. We bridge the gap between government and the public, providing robust research and analysis to help clients evaluate what works. -

UFGS 06 10 00 Rough Carpentry

************************************************************************** USACE / NAVFAC / AFCEC / NASA UFGS-06 10 00 (August 2016) Change 2 - 11/18 ------------------------------------ Preparing Activity: NAVFAC Superseding UFGS-06 10 00 (February 2012) UNIFIED FACILITIES GUIDE SPECIFICATIONS References are in agreement with UMRL dated July 2021 ************************************************************************** SECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS DIVISION 06 - WOOD, PLASTICS, AND COMPOSITES SECTION 06 10 00 ROUGH CARPENTRY 08/16, CHG 2: 11/18 PART 1 GENERAL 1.1 REFERENCES 1.2 SUBMITTALS 1.3 DELIVERY AND STORAGE 1.4 GRADING AND MARKING 1.4.1 Lumber 1.4.2 Structural Glued Laminated Timber 1.4.3 Plywood 1.4.4 Structural-Use and OSB Panels 1.4.5 Preservative-Treated Lumber and Plywood 1.4.6 Fire-Retardant Treated Lumber 1.4.7 Hardboard, Gypsum Board, and Fiberboard 1.4.8 Plastic Lumber 1.5 SIZES AND SURFACING 1.6 MOISTURE CONTENT 1.7 PRESERVATIVE TREATMENT 1.7.1 Existing Structures 1.7.2 New Construction 1.8 FIRE-RETARDANT TREATMENT 1.9 QUALITY ASSURANCE 1.9.1 Drawing Requirements 1.9.2 Data Required 1.9.3 Humidity Requirements 1.9.4 Plastic Lumber Performance 1.10 ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS 1.11 CERTIFICATIONS 1.11.1 Certified Wood Grades 1.11.2 Certified Sustainably Harvested Wood 1.11.3 Indoor Air Quality Certifications 1.11.3.1 Adhesives and Sealants 1.11.3.2 Composite Wood, Wood Structural Panel and Agrifiber Products SECTION 06 10 00 Page 1 PART 2 PRODUCTS 2.1 MATERIALS 2.1.1 Virgin Lumber 2.1.2 Salvaged Lumber 2.1.3 Recovered Lumber -

06 10 00 --- Rough Carpentry

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS DIVISION 6 WOODS & PLASTICS 06 10 00 • ROUGH CARPENTRY SECTION INCLUDES Dimensional Wood Framing Sheathing Prefabricated Trusses Wood Blocking Engineered Wood Framing Termite Shield RELATED SECTIONS 03 30 00 Concrete 06 20 00 Finish Carpentry 06 50 00 Structural Plastics & Composites 06 65 00 Plastic and Composite Trim 07 62 00 Sheet Metal Trim & Flashing ABBREVIATIONS-TESTING, CERTIFYING AND GRADING AGENCIES AITC- American Institute of Timber Construction www.aitc-glulam.org ALSC- American Lumber Standards Committee www.alsc.org ANSI- American National Standards Institute www.ansi.org APA- The Engineered Wood Association, (formerly American Plywood Association) www.apawood.org AWPA- American Wood Protection Association www.awpa.com CSA- Canadian Standards Association www.csa.ca FSC- Forest Stewardship Council www.fscus.org NIST- National Institute for Standards and Technology www.nist.gov SFI-Sustainable Forest Initiative www.sfiprogram.org TPI- Truss Plate Institute www.tpint.org LOAD CALCULATIONS DESIGN Calculate loads and specify the fiber stress for lumber. Avoid over-designing that will result in unnecessarily high material costs. Spruce, Pine or Fir should be adequate for most conditions; provide a rationale for any other species. ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES PRODUCTS Use of wood from well-managed forests is preferred. Specify one or more of the following standards: Forest Stewardship Council (FSC); Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI); or Canadian Standards Association (CSA). Using certified wood encourages a well-managed forest industry. Look for engineered wood products with certified wood content, recycled or recovered wood, and/or products that are produced within 500 miles of the project site. The use of engineered wood should be evaluated on R 06 10 00 ROUGH CARPENTRY………. -

Rough Carpentry

SECTION 06112 ROUGH CARPENTRY PART 1 – GENERAL 1.01 REFERENCES A. APA (American Plywood Association) B. AWPA (American Wood Preservers Association) Book of Standards C. WCLIB (West Coast Lumber Inspection Bureau) D. WWPA (Western Wood Products Association) E. Structural Notes 1.02 DELIVERY, STORAGE, AND PROTECTION A. See Section 01600 – Material and Equipment: Transport, handle, store and protect products. 1.03 COORDINATION A. Coordinate and provide solid blocking for wall and ceiling mounted items. B. Coordinate sequencing and installation of gypsum wallboard for firewall and ceiling assemblies. 1.04 ALTERNATES A. See Section 01030 for bidding alternates affecting the work of this Section. 1.05 COLORS A. Colors are specified in Colors/Materials Schedule. 1.06 SUSTAINABLE BUILDING REQUIREMENTS A. See Section 01011 for sustainable building requirements affecting the work of this Section. PART 2 – PRODUCTS 2.01 LUMBER MATERIALS A. Lumber Grading Rules: WCLIB or WWPA. B. Maximum Moisture Content: 19%. 2.02 ACCESSORIES A. Nail Fasteners: See Structural General Notes; use hot-dipped galvanized steel (American or Canadian manufacture). B. Joist Hangers and Framing Connectors: Galvanized steel, sized to suit loads, joints and framing conditions; Simpson, Bowman Morton Manufacturing & Machine, Seattle, WA or approved. Refer to Structural General Notes. C. Anchor bolts, Bolts, Nuts, and Washers: Refer to Structural General Notes. Non- structural anchor bolts shall conform to ASTM A307, hot-dipped galvanized at exterior locations or where exposed to exterior environment. D. Water resistant Barrier Building Paper: No. 15 Asphalt Felt. E. Metal Flashing at Openings: 24 gauge stainless steel. 2.03 WOOD TREATMENT A. Wood Preservative (Pressure Treatment): AWPA Treatment LP-2, C2 for lumber, C9 for plywood. -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

Marathon Petroleum Educational Reimbursement Plan

Educational Reimbursement Plan Marathon Petroleum Educational Reimbursement Plan Effective January 1, 2021 Educational Reimbursement Plan Table of Contents I. Objective ..................................................................................................................................................................1 II. Employee Eligibility.................................................................................................................................................1 III. Tuition Assistance ...................................................................................................................................................1 IV. Certification and Licensing Assistance ...............................................................................................................6 V. Approval ...................................................................................................................................................................9 VI. Taxability of Educational Reimbursement Benefits ...........................................................................................9 VII. Participation by Associated Companies and Organizations ............................................................................9 VIII. Transfers and Termination of Employment ....................................................................................................... 10 IX. Further Information ............................................................................................................................................. -

Timber Bridges Design, Construction, Inspection, and Maintenance

Timber Bridges Design, Construction, Inspection, and Maintenance Michael A. Ritter, Structural Engineer United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Ritter, Michael A. 1990. Timber Bridges: Design, Construction, Inspection, and Maintenance. Washington, DC: 944 p. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author acknowledges the following individuals, Agencies, and Associations for the substantial contributions they made to this publication: For contributions to Chapter 1, Fong Ou, Ph.D., Civil Engineer, USDA Forest Service, Engineering Staff, Washington Office. For contributions to Chapter 3, Jerry Winandy, Research Forest Products Technologist, USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. For contributions to Chapter 8, Terry Wipf, P.E., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Structural Engineering, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. For administrative overview and support, Clyde Weller, Civil Engineer, USDA Forest Service, Engineering Staff, Washington Office. For consultation and assistance during preparation and review, USDA Forest Service Bridge Engineers, Steve Bunnell, Frank Muchmore, Sakee Poulakidas, Ron Schmidt, Merv Eriksson, and David Summy; Russ Moody and Alan Freas (retired) of the USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory; Dave Pollock of the National Forest Products Association; and Lorraine Krahn and James Wacker, former students at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. In addition, special thanks to Mary Jane Baggett and Jim Anderson for editorial consultation, JoAnn Benisch for graphics preparation and layout, and Stephen Schmieding and James Vargo for photographic support. iii iv CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 TIMBER AS A BRIDGE MATERIAL 1.1 Introduction .............................................................................. l- 1 1.2 Historical Development of Timber Bridges ............................. l-2 Prehistory Through the Middle Ages ....................................... l-3 Middle Ages Through the 18th Century ................................... l-5 19th Century ............................................................................ -

Action Plan on Bullying – Report of the Anti

Action Plan On Bullying Report of the Anti-Bullying Working Group to the Minister for Education and Skills January 2013 Anti-Bullying Action Plan – Design Template Table of Contents Programme for Government Commitment ................................................................ - 5 - Welcome from Minister ................................................................................................ - 6 - Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... - 8 - Introduction and Background .................................................................................... - 11 - What is bullying? ......................................................................................................... - 15 - Impact of bullying ...................................................................................................... - 31 - What do children and young people say about bullying? .................................... - 45 - What are schools already required to do? .............................................................. - 51 - Do we need more legislation? .................................................................................. - 69 - Responses to bullying in schools............................................................................... - 75 - This is not a problem schools can solve alone ........................................................ - 93 - Action Plan on Bullying ........................................................................................... -

The Case for Careers Education and Guidance for 14-19 Year Olds

The Case for Careers Education and Guidance for 14-19 Year Olds Marian Morris March 2004 National Foundation for Educational Research An overview of NFER’s research findings on careers education and guidance The recent interim report by the Working Group on 14-19 Reform (DfES, 2004) brought into sharp focus the need for a coherent, integrated and well planned careers education and guidance programme in schools and colleges. In order for young people to make the most of the opportunities in the proposed 14-19 curriculum, Tomlinson argued that young people ‘must be prepared with the skills and self-awareness to exercise their choices effectively’. What are these skills? How compelling is the evidence that such skills can support young people in making effective choices about their future? How well prepared are schools and colleges to support their students’ career development? This briefing paper explores some of the summarised findings from a number of large-scale research studies conducted at NFER (mostly on behalf of the DfES and its predecessor Departments, but also on behalf of a number of different careers services) over the last decade. It argues that it is possible to identify the skills that promote successful transition and traces some of the links between successful transition and programmes of careers education and guidance. It also suggests that, in the light of the Tomlinson Report (2004), the recent National Audit Office report (2004) and the findings from current research on transition from schools engaged in Excellence in Cities and Aimhigher (Morris and Rutt, 2003); the conclusions from this earlier research are equally pertinent today.