Transcript Is Based on an Interview Recorded by Illinois Public Media/WILL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D

Names 39.2 (June 1991) Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D. Lawson1 Abstract Samples of men's and women's names drawn from English language editions of Israeli telephone directories identify the most common names in current usage. These names, categorized into Biblical, Traditional, Modern Hebrew, and Non-Hebrew groups, indicate that for both men and women over 90 percent come from Hebrew, with the Bible accounting for over 70 percent of the male names and about 40 percent of the female. Pronunciation, meaning, and Bible citation (where appropriate) are given for each name. ***** The State of Israel represents a tremendous opportunity for names research. Immigrants from traditions and cultures as diverse as those of Yemen, India, Russia, and the United States have added their onomastic contributions to the already existing Jewish culture. The observer accustomed to familiar first names of American Jews is initially puzzled by the first names of Israelis. Some of them appear to be biblical, albeit strangely spelled; others appear very different. What are these names and what are their origins? Benzion Kaganoffhas given part of the answer (1-85). He describes the evolution of modern Jewish naming practices and has dealt specifi- cally with the change of names of Israeli immigrants. Many, perhaps most, of the Jews who went to Israel changed or modified either personal or family name or both as part of the formation of a new identity. However, not all immigrants changed their names. Names such as David, Michael, or Jacob required no change since they were already Hebrew names. -

Dr. Hanchen Huang's CV

Hanchen Huang Dean of Engineering & Lupe Murchison Foundation Chair Professor, UNT ([email protected]) Co-founder, MesoGlue Inc. ([email protected]); Cell phone: 860-771-0771 A. Scholarship ................................................................................................................................. 2 A.1 Science and Technology of Metallic Nanorods .................................................................... 2 A.2 Other Disciplines .................................................................................................................. 3 B. Leadership in Academia ............................................................................................................. 3 B.1 Leadership on University Campuses .................................................................................... 4 B.2 Leadership in Professional Societies .................................................................................... 4 C. Bio-sketch ................................................................................................................................... 5 D. Honors, Awards, and Recognitions ............................................................................................ 5 E. Work Experiences ....................................................................................................................... 6 F. Educational Background ............................................................................................................. 8 G. Research Grants ......................................................................................................................... -

Our Lady of the Assumption Parish 545 Stratfield Road Fairfield, CT 06825-1872 Tel

Our Lady of the Assumption Parish 545 Stratfield Road Fairfield, CT 06825-1872 Tel. (203) 333-9065 Fax: (203) 333-2562 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.olaffld.org “Ad Jesum per Mariam” To Jesus through Mary. Clergy/Lay Leadership Rev. Peter A. Cipriani, Pastor Rev. Michael Flynn, Parochial Vicar Deacon Raymond John Chervenak Deacon Robert McLaughlin Michael Cooney, Director of Music Daniel Ford, Esq., Trustee Masses (Schedules subject to change) Saturday Vigil Mass: 4 PM Sunday Masses: 7:30 AM, 9 AM 10:30 AM and 12:00 PM (Subject to change) Morning Daily Mass: (Mon.-Sat.) 7:30 AM Evening Daily Mass: (Mon.-Fri.) 5:30 PM Holy Days: See Bulletin for schedule Sacrament of Reconciliation Saturday: 1:30– 2:30 PM or by appointment. Every Tuesday: 7-8:00 PM Rosary/Divine Mercy Chaplet 7 AM Monday-Saturday, Rosary 8 AM First Saturday of each month, Rosary 3 PM Monday-Friday, Divine Mercy Chaplet and Rosary Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults (RCIA) Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Anyone interested in becoming a Roman Catholic becomes a part of this First Friday of each month from 8 AM process, as can any adult Catholic who has not received all the Sacraments of Friday to 7:15 AM Saturday. To volunteer initiation. For further information contact the Faith Formation office. contact Grand Knight, Michael Lauzon at (203) 817-7528. Sacrament of Baptism This Sacrament is celebrated on Sundays at 1:00 PM. It is required that Novenas parents participate in a Pre-Baptismal class. Classes are held on the third Miraculous Medal-8 AM. -

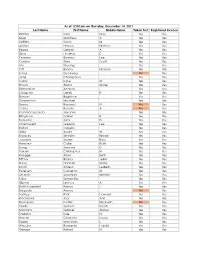

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

The Family Bible Preservation Project Has Compiled a List of Family Bible Records Associated with Persons by the Following Surname

The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry THE FAMILY BIBLE PRESERVATION PROJECT HAS COMPILED A LIST OF FAMILY BIBLE RECORDS ASSOCIATED WITH PERSONS BY THE FOLLOWING SURNAME: DANIELSON Scroll Forward, page by page, to review each bible below. Also be sure and see the very last page to see other possible sources. For more information about the Project contact: EMAIL: [email protected] Or please visit the following web site: LINK: THE FAMILY BIBLE INDEX Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: DANIELSON UNDER THIS SURNAME - A RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: THE RECORD HERE BELOW REFERENCED IS NOT ACTUALLY A FAMILY BIBLE. BUT RATHER A UTAH PIONEER HISTORY FAMILY OF: DANIELSON, AMANDA ADELAIDE MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS RECORD - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: DAUGHTERS OF THE UTAH PIONEERS FILE/RECD: D.U.P. FAMILY HISTORY - DANIELSON, AMANDA ADELAIDE [ 19 Aug 1866 - 1 Oct 1942 ] THE FOLLOWING INTERNET HYPERLINKS CAN BE HELPFUL IN FINDING MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS RECORD: LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK GROUP CODE: 67 Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: DANIELSON UNDER THIS SURNAME - A RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: THE RECORD HERE BELOW REFERENCED IS NOT ACTUALLY A FAMILY BIBLE. BUT RATHER A UTAH PIONEER HISTORY FAMILY OF: DANIELSON, CLAUS DANIEL CARLSON MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS RECORD - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: DAUGHTERS OF THE UTAH PIONEERS FILE/RECD: D.U.P. -

2021 ABOS WLA Knowledge Sources

The American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Web-Based Longitudinal Assessment ABOS WLA 2021 Knowledge Sources 2021 ABOS Required Knowledge Source 1. Leadership, Communication, and Negotiation Across a Diverse Workforce: An AOA Critical Issues Symposium. Clohisy D, Yaszemski M, Lipman J. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Jun 21;99(12):e60. 2020 ABOS Required Knowledge Source 1. Managing stress in the orthopaedic family: avoiding burnout, achieving resilience. Sargent M, Sotile W, Sotile M, Rubash H, Vezeridis P, Harmon L, Barrack R. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Apr 20;93(8):e40. 2019 ABOS Required Knowledge Source 1. Leading the Way to Solutions to the Opioid Epidemic: AOA Critical Issues. Seymour RB, Ring D, Higgins T, Hsu JR. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Nov 1;99(21):e113(1-10). 1 General Orthopaedics 1. Controversies in the management of distal radius fractures. Koval K, Haidukewych GJ, Service B, Zirgibel BJ. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014 Sep;22(9):566-575 . 2. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014 Apr;22(4):256-60. 3. Open Tibial Fractures: Updated Guidelines for Management. Mundi R, Chaudhry H, Niroopan G, Petrisor B, Bhandari M. JBJS Rev. 2015 Feb 3;3(2). 4. Surgical Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: Evidence-based Guideline. McGrory BJ, Weber KL, Jevsevar DS, Sevarino K. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016 Aug;24(8):e87-93. 5. Complications of shoulder arthroscopy. Moen TC, Rudolph GH, Caswell K, Espinoza C, Burkhead WZ Jr, Krishnan SG. -

Danny Daniels: a Life of Dance and Choreography

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 Danny Daniels: A life of dance and choreography Louis Eric Fossum Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Fossum, Louis Eric, "Danny Daniels: A life of dance and choreography" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2357. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANNY DANIELS: A LIFE OF DANCE AND CHOREOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies: Theatre 'Arts and Communication Studies by Louis Eric Fossum June 2003 DANNY DANIELS: A LIFE OF DANCE AND CHOREOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Louis Eric Fossum June 2003 Approved by: Processor Kathryn Ervin, Advisor Department of Thea/fer Arts Department of Theater Arts Dr. Robin Larsen Department of Communications Studies ABSTRACT The career of Danny Daniels was significant for its contribution to dance choreography for the stage and screen, and his development of concept choreography. Danny' s dedication to the art of dance, and the integrity of the artistic process was matched by his support and love for the dancers who performed his choreographic works. -

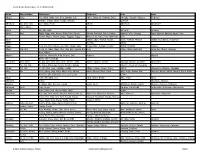

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

Member-Roster-2020-08-10.Pdf

First Name Last Name Display Name Informal Name Email Address Member Class Member Class Code Member Grade Member Since Date Chapter Primary Facility Name Primary Facility Phone Number Eric Fernandez Eric E. Fernandez Eric [email protected] Associate Assistant Professional B-8 Associate 2020-03-06 105MA Sandbaggers Practice Range (781) 826-1234 Michael Abate Michael J. Abate, PGA Michael [email protected] Assistant Professional A-8 Member 2018-04-02 105CAPE Vineyard Golf Club (508) 627-8930 Andrew Abbott Andrew T. Abbott Andrew [email protected] Associate Assistant Professional B-8 Associate 2018-05-29 105MA The Kittansett Club (508) 748-0192 Jared Adams Jared J. Adams Jared [email protected] Associate Assistant Professional B-8 Associate 2017-11-15 105RI Point Judith Country Club (401) 792-9770 Nathaniel Adelson Nathaniel H. Adelson, PGA Nathaniel [email protected] Director of Golf A-4 Member 2013-03-15 105RI Alpine Country Club (401) 944-9760 Nicholas Adjutant Nicholas A. Adjutant Nicholas [email protected] Associate Assistant Professional B-8 Associate 2019-03-11 105NH Omni Mount Washington Hotel & Resort (603) 278-1000 Eric Aguiar Eric J. Aguiar Eric [email protected] Associate Assistant Professional B-8 Associate 2020-06-15 105NH Lake Winnipesaukee Golf Club (603) 569-3055 Toby Ahern Toby Ahern, PGA Toby [email protected] Director of Golf A-4 Member 1989-12-01 105MA Nahant Golf Club (781) 581-0840 Norm Alberigo Norm Alberigo, PGA Norm [email protected] Head Professional A-1 Member 1988-08-01 105RI Agawam Hunt (401) 434-3254 Michael Albrecht Michael D. -

Proquest Dissertations

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI® Playing the Cultural Field The Role of Outsourcing and Cultural Intermediaries in Art Museum Development Ann Danilevich A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2009 © Ann Danilevich, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63188-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63188-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.