Journal of Cosmetic Dentistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class III Malocclusion Treated Non-Surgically with Invisalign, Mandibular Fixed Appliances and Mandibular Tads by Randy J

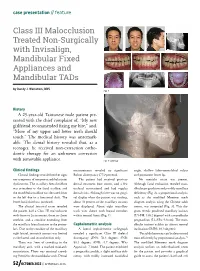

case presentation // feature Class III Malocclusion Treated Non-Surgically with Invisalign, Mandibular Fixed Appliances and Mandibular TADs by Randy J. Weinstein, DDS Fig. 1 History A 25-year-old Taiwanese male patient pre- sented with the chief complaint of, “My new girlfriend recommended fixing my bite,” and, “More of my upper and lower teeth should touch.” The medical history was unremark- able. The dental history revealed that, as a teenager, he received non-extraction ortho- dontic therapy for an unknown correction with removable appliance. Fig. 2: Overlay Clinical findings measurements revealed no significant angle, shallow labio-mentolabial sulcus Clinical findings revealed neither signs Bolton discrepancy (77.9 percent). and prominent lower lip. nor symptoms of temporomandibular joint The patient had received previous No mentalis strain was present. dysfunction. The maxillary dental midline dental treatment (one crown, and a few Although facial evaluation revealed man- was coincident to the facial midline, and occlusal restorations) and had regular dibular prognathism and possibly maxillary the mandibular midline was deviated 2mm dental visits. Although there was no gingi- deficiency (Fig. 2), a proportional analysis, to the left due to a functional shift. The val display when the patient was smiling, such as the modified Moorrees mesh lower facial third was increased. about 70 percent of the maxillary incisors diagram analysis using the Chinese adult The clinical intraoral exam revealed were displayed. About eight maxillary norms, was computed (Fig. 3). This dia- the patient had a Class III malocclusion teeth were shown with buccal corridors gram reveals proclined maxillary incisors with 0mm to 2mm overjet, 0mm to -2mm within normal limits (Fig. -

An Overview on Interproximal Enamel Reduction

DENTISTRY ISSN 2377-1623 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/DOJ-1-104 Open Journal Review An Overview on Interproximal Enamel *Corresponding author Reduction Yanqi Yang Assistant Professor in Orthodontics Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Deborah Chee#, Chong Ren# and Yanqi Yang* Hong Kong, 2/F, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Sai Ying #equally contributed Pun, Hong Kong, China Tel. +852-28590252 Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong Fax: +852-25593803 SAR, China E-mail: [email protected] Volume 1 : Issue 1 ABSTRACT Article Ref. #: 1000DOJ1104 Ever since its first introduction seven decades ago, there has been continuous advance- ment of the concept and technique of Interproximal enamel reduction (IPR). It’s demonstrated Article History that with correct case selection and clinical performance, IPR is safe and effective for alleviat- Received: October 28th, 2014 ing crowding, improving dental and gingival aesthetics as well as facilitating post-treatment Accepted: December 5th, 2014 stability. The fulfilment of treatment outcomes depends on careful pre-treatment examination Published: December 8th, 2014 and planning, appropriate clinical procedures and effective post-treatment protection. This re- view aims to provide a general introduction to IPR in terms of its history background, risks and Citation benefits and clinical performance. Chee D, Ren C, Yang Y. An overview on interproximal enamel reduction. Dent Open J. 2014; 1(1): 14-18. doi: KEYWORDS: Interproximal enamel reduction; Orthodontic treatment; Crowding; Tooth re- 10.17140/DOJ-1-104 contouring. INTRODUCTION Interproximal enamel reduction (IPR) also described as “stripping”, “reproximation” and “slenderizing” has been applied in clinical orthodontics for almost seven decades.1,2 By removing part of the enamel tissue from the interproximal contact area, this technique has been proved to be effective in improving dental alignment, stability and aesthetics. -

Proroot® MTA (Mineral Trioxide Aggregate) Root Canal Repair Material

® ProRoot MTA EN (Mineral Trioxide Aggregate) Root canal repair material RX ONLY DENTAL USE ONLY DIRECTIONS FOR USE PROROOT® MTA 1) INDICATIONS FOR USE ProRoot® MTA root repair material is indicated for use as: • A root-end filling material; • For the repair of root canals as an apical plug during apexification; • For repair of root perforations during root canal therapy; • As a consequence of internal resorption; • As a pulp capping material; • Pulpotomy of primary teeth in the child (ages >2-12 years) and adolescent (ages >12-21 years) pediatric patient populations. 2) CONTRAINDICATIONS None known. 3) WARNINGS ProRoot® MTA root repair material is a powder consisting of fine, hydrophilic particles that set in the presence of moisture. Hydration of the powder creates a colloidal gel that solidifies to form a strong impermeable barrier that fully cures over a four-week period. 4) PRECAUTIONS • ProRoot® MTA root repair material must be stored in a dry area to avoid degradation by moisture. • ProRoot® MTA root repair material must be kept in its sealed packaging prior to use to avoid degradation by moisture. • ProRoot® MTA root repair material must be placed intra-orally immediately after mixing with liquid, to prevent dehydration during setting. B EN PROR DFU MAS / Rev.05 / 05-2017 (Old ZF 190279.EN) 1/6 • When using ProRoot® MTA in an aesthetic zone, the clinician should consider the procedure being performed, the surface area exposed and the other restorative materials being used to achieve best results. • Avoid skin contact to prevent irritation and possible allergic response. If contact with skin occurs, immediately remove material with cotton and wash thoroughly with water and soap. -

Surgical Repair of Root and Tooth Perforations JOHN D

Endodontic Topics 2005, 11, 152–178 Copyright r Blackwell Munksgaard All rights reserved ENDODONTIC TOPICS 2005 1601-1538 Surgical repair of root and tooth perforations JOHN D. REGAN, DAVID E. WITHERSPOON & DEBORAH M. FOYLE A root perforation is a mechanical or pathological communication formed between the supporting periodontal apparatus of the tooth and the root canal system. Three broad categories of etiological factors exist and these are procedural mishaps, resorption and caries. The diagnosis, management and repair of root perforations require skill and creative thinking. Unfortunately, much of what has been written on the subject of root perforation repair is unsubstantiated and empirical in nature and contributes little to evidence-based support for any specific repair procedure. However, perforation repair frequently provides a very attractive and frequently successful alternative to extraction of the involved tooth. In recent years, the procedure has become more predictable owing to the development of new materials, techniques and procedures. Introduction many perforations has been facilitated by the use of improved magnification and illumination provided by A root perforation is a mechanical or pathological the use of loupes or the surgical operating microscope communication formed between the supporting per- (SOM) (9, 10, 15–28). In practice, however, the iodontal apparatus of the tooth and the root canal indications for surgical correction of root perforations system (1). Perforations result in the destruction of the are being eroded from two directions: on the one hand dentine root wall or floor along with the investing by the improved non-surgical management of perfora- cementum. This communication compromises the tions and on the other by the use of implants. -

Orthodontics & Esthetic Dentistry

SCIENTIFIC SESSION TORONTO 2016 ORTHODONTICS & ESTHETIC DENTISTRY: MISSION POSSIBLE! A Broader Approach to Interdisciplinary Esthetic Treatment David M. Sarver, DMD, MS AACD 2016 TORONTO: THURSDAY MORNING “TRIPLE PLAY!” One Session. One Theme. Three Big Hitters. Dr. David M. Sarver, along with Dr. J. William Robbins and Dr. Jeffrey Rouse, will “cover the bases” on diagnosis, decision making, and treatment planning. These three “big hitters” will be presenting sequentially in the same room on Thursday, April 28, 2016. Dr. Sarver will present “Orthodontics— How it Has Changed and What You Really Want to Know!” This article discusses how orthodontics is incorporating smile design principles into its overall functional and esthetic treatment goals. Abstract For decades, dentistry has been evolving into a Patients seeking esthetic profession that is extremely multifaceted and varied in its approach to both smile and facial esthetics. treatment today wish to The coordination of macro esthetics (the face), mini enhance their appearance esthetics (the smile), and micro esthetics (the dental for improved self-esteem esthetic component) offers a complete approach to esthetic planning. This article presents an expanded and quality of life. vision of esthetic treatment designed to take readers to another level of facial, smile, and dental esthetic planning that can elevate patient outcomes. Key Words: macro esthetics, mini esthetics, micro esthetics, orthodontics, smile design 14 Winter 2016 • Volume 31 • Number 4 Sarver Figure 1: In both multidisciplinary and orthodontic diagnosis, three esthetic divisions are advocated: macro esthetics (the face), mini esthetics (the smile), and micro esthetics (the teeth). …there are principles of cosmetic dentistry that orthodontists can use to enhance their work to provide a superior esthetic outcome. -

Dental Dam Utilization by Dentists in an Intramural Faculty Practice

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass General Practice Publications Dept. of General Practice 2019 Dental Dam Utilization by Dentists in an Intramural Faculty Practice Terence A. Imbery Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Caroline K. Carrico Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/genp_pubs Part of the Dentistry Commons ©2019 The Authors. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/genp_pubs/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of General Practice at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in General Practice Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Received: 22 February 2019 Revised: 12 April 2019 Accepted: 15 April 2019 DOI: 10.1002/cre2.191 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dental dam utilization by dentists in an intramural faculty practice Terence A. Imbery1 | Caroline K. Carrico2,3 1 Department of General Practice, Virginia Abstract Commonwealth University School of Dentistry, Richmond, Virginia Objectives: From casual observation of our colleagues, only a few individuals use the 2 Department of Oral Health Promotion and dental dam for operative procedures in their faculty practice. The purpose of this study Community Outreach, Oral Health Services Research Core, VCU Philips Institute for Oral was to obtain faculty perceptions of the dental dam, quantify its utilization in their Health Research, Virginia Commonwealth intramural faculty practice, and determine the factors that influence dental dam usage. -

Treatment Planning in Conservative Dentistry

Dental Science - Review Article Treatment planning in conservative dentistry Andamuthu Sivakumar, Vinod Thangaswamy1, Vaiyapuri Ravi Department of ABSTRACT Conservative Dentistry A patient attending for treatment of a restorative nature may present for a variety of reasons. The success is and Endodontics, built upon careful history taking coupled with a logical progression to diagnosis of the problem that has been Vivekanandha Dental College for Women, presented. Each stage follows on from the preceding one. A fitting treatment plan should be formulated and Tiruchengodu, 1Oral and should involve a holistic approach to what is required. Maxillofacial Surgery, JKKN Dental College and Hospital, Kumarapal Ayam, India Address for correspondence: Dr. Andamuthu Sivakumar, E-mail: tirupurdental@gmail. com Received : 01-12-11 Review completed : 02-01-12 Accepted : 26-01-12 KEY WORDS: Diagnosis, history, holistic, restorative, treatment plan he purpose of dental treatment is to respond to a patient’s understanding of the disease processes and their relationship T needs. Each patient, however, is as unique as a fingerprint. to each other. Fundamental is that the diagnosed lesion be Treatment therefore should be highly individualized for the considered in context with its host, the patient, and the total patient as well as the disease.[1] environment to which it is subjected. Careful weighing of all information will lead to an authoritative opinion regarding Treatment Planning treatment. So, a sound treatment plan [Table 1] depends on thorough patient evaluation, dentist expertise, understanding 1. It is a carefully sequenced series of services designed to the indications and contraindications, and prediction of eliminate or control etiologic factor.[2] patient’s response to treatment. -

CONDOM Dos & DON'ts

CONDOM DOs & DON’Ts PROTECT YOURSELF DO use a condom every time you have sex. CONDOMS REDUCE THE RISK DO put on a condom before having sex. DO read the package and check the expiration date. DO make sure there are no tears or defects. DO store condoms in a cool, dry place. Additional information is available at health.nd.gov/HIV or DO use latex or polyurethane condoms. by calling the North Dakota DO use water or silicone-based lubricant to Department of Health prevent breakage. at 701.328.2378. DON’T store condoms in your wallet. Heat and friction can damage them. DON’T use nonoxynol-9 (a spermicide), as this can cause irritation. DON’T use oil-based products like baby oil, lotion, petroleum jelly, or cooking oil because they will cause the condom to break. DON’T use more than one condom at a time. DON’T reuse a condom. What is a Dental Dam? Dental Dams are latex sheets used 1 2 between the mouth and vagina or anus during ORAL SEX. Use dental Carefully open and remove condom from Place condom on the head of the erect, dams to prevent STD infections in wrapper. Don’t forget to check the hard penis. If uncircumcised, pull back expiration date. the foreskin first. your mouth or throat. ONE IN TWO SEXUALLY ACTIVE PEOPLE WILL CONTRACT AN STD BY AGE 25. 3 4 Pinch air out of the tip of the condom. Unroll condom all the way down the penis. After sex, but before pulling out, hold Carefully remove the condom and Be safe. -

Table of Contents

Houston North Loop (HNL) Houston Southwest (HSW) ABHES Main Campus ABHES Non-Main Campus of HNL 240 Northwest Mall 7322 Southwest Freeway, Suite 110 Houston, TX 77092 Houston, Texas 77074 (713) 425-3100 (713) 470-2427 San Antonio (SA) Fort Worth (FW) ABHES Non-Main Campus of HNL ABHES Non-Main Campus of HNL 4738 N. W. Loop 410 4248 North Freeway San Antonio, Texas 78229 Fort Worth, Texas 76137 (210) 298-3600 (817) 632-5900 Austin Campus (AUS) Dallas Campus (DAL) ABHES Main Campus ABHES Non-Main Campus of AUS 6330 East Highway 290, Suite 180 8390 LBJ Freeway, Suite 300 Austin, Texas 78723 Dallas, Texas 75243 (512) 617-5700 (214) 420-3400 McAllen Campus (MCA) ABHES Non-Main Campus of HNL 1917 Nolana Avenue, Suite 100 McAllen, Texas 78504 (956) 800-1500 School Catalog Volume XVI July 2017 Effective July 1, 2017 Accredited by Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools Approved and regulated by Texas Workforce Commission, Career Schools and Colleges, Austin, Texas; and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Austin, Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF INSTITUTIONAL MISSION, PHILOSOPHY, AND PURPOSE ..................................... 6 SCHOOL HISTORY/STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP .......................................................................... 6 APPROVALS/ACCREDITATION ...................................................................................................... 7 DESCRIPTION OF FACILITY ........................................................................................................... 7 PROFESSIONAL ADVISORY -

An Overview on Interproximal Enamel Reduction Review

DENTISTRY ISSN 2377-1623 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/DOJ-1-104 Open Journal Review An Overview on Interproximal Enamel *Corresponding author Reduction Yanqi Yang Assistant Professor in Orthodontics Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Deborah Chee#, Chong Ren# and Yanqi Yang* Hong Kong, 2/F, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Sai Ying #equally contributed Pun, Hong Kong, China Tel. +852-28590252 Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong Fax: +852-25593803 SAR, China E-mail: [email protected] Volume 1 : Issue 1 ABSTRACT Article Ref. #: 1000DOJ1104 Ever since its first introduction seven decades ago, there has been continuous advance- ment of the concept and technique of Interproximal enamel reduction (IPR). It’s demonstrated Article History that with correct case selection and clinical performance, IPR is safe and effective for alleviat- Received: October 28th, 2014 ing crowding, improving dental and gingival aesthetics as well as facilitating post-treatment Accepted: December 5th, 2014 stability. The fulfilment of treatment outcomes depends on careful pre-treatment examination Published: December 8th, 2014 and planning, appropriate clinical procedures and effective post-treatment protection. This re- view aims to provide a general introduction to IPR in terms of its history background, risks and Citation benefits and clinical performance. Chee D, Ren C, Yang Y. An overview on interproximal enamel reduction. Dent Open J. 2014; 1(1): 14-18. doi: KEYWORDS: Interproximal enamel reduction; Orthodontic treatment; Crowding; Tooth re- 10.17140/DOJ-1-104 contouring. INTRODUCTION Interproximal enamel reduction (IPR) also described as “stripping”, “reproximation” and “slenderizing” has been applied in clinical orthodontics for almost seven decades.1,2 By removing part of the enamel tissue from the interproximal contact area, this technique has been proved to be effective in improving dental alignment, stability and aesthetics. -

Movingnot Removing Enamel

VOLUME 01 / ISSUE 01 The Academy for Clear Aligner Therapy the AmericanJournal Academy of Cosmetic Orthodontics MOVING not removing ENAMEL. PEER-REVIEWED SOLUTIONS that will make Clear Aligner Treatment THAT MUCH EASIER. Like this Journal? start receiving your quarterly issue today! The official academy for Clear Aligner Therapy. Become a member TODAY! www.aacortho.com AACO Board Members Dr. David Galler: President the Dr. Mark Hodge: Vice President Dr. Perry Jones: Director of Education Dr. Jeffrey Galler: Editor AmericanJournal Academy of Cosmetic Orthodontics Dr. Len Tau: Director of Media Relations Dr. Bruce McFarlane: Orthodontist, Advisory Board Article is Peer Reviewed Article offers CE Credit at www.aacortho.com Dr. David Harrnick: Orthodontist, Advisory Board Dr. Sandi Bosin: Orthodontist, Editorial Board Case Reports Dr. Peter Rivolli: ClearCorrect Clinical Expert Dr. Yana Shampanksy: Invisalign Expert 2 Upper Lateral Incisor Crossbite with Dr. Lori Trost: MTM Clinical Expert Lower Premolar in Lingual Version by Dr. Cathy Sherry 4 Invisalign Correction of a Teenager’s Class 2 Division 1 Malocclusion by Dr. David J. Harnick 8 Upper Arch Spacing and Lower Editorial Arch Overcrowding I’ve been reading numerous by Dr. David Galler dental journals every Practice Development month for many years, 14 The Economics of Buying vs. but don’t remember ever Renting Your Next Office actually reading an editorial completely, from beginning by Jake Jacklich to end. 16 “Doctor, I’ve been your patient for I resolved that in this, my first 10 years; how come you never editorial for the Journal of the American mentioned orthodontics before?” Academy of Cosmetic Orthodontics, by Gary Kadi I would write an editorial that readers Retention would, in fact, read from the very first to the very last word. -

Orthodontic Treatment of Class Three Malocclusion Using Clear Aligners

Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research 9 (2019) 360–362 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jobcr Case study Orthodontic treatment of class three malocclusion using clear aligners: A case report T ∗ Edoardo Staderini , Simonetta Meuli, Patrizia Gallenzi Institute of Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Largo A, Gemelli N°1, Rome, RM, 00168, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Class III malocclusion is a growth-related challenging condition for orthodontists. We present a case of a 11-year- Angle class III old girl with a skeletal class III malocclusion with bilateral cross bite, and a functional shift of the lower dental Clear aligner midline. A multiphase clear aligners' treatment was scheduled with the aim of removing all dental interferences Interceptive orthodontic treatment which involved an anterior displacement of the mandible. At one-year follow-up, clear aligners’ therapy resulted in skeletal and dental improvements. Clear aligners therapy represents a valid alternative to fixed appliance therapy in the early interception of class III malocclusion. The present manuscript was prepared following the CARE guidelines. 1. Introduction relation was noticed.4 At intraoral evaluation, the patient presented a late mixed dentition with a bilateral class III malocclusion, along with a Class III malocclusion is a challenging dentoalveolar growth defor- functional mandibular lateral deviation towards the patient's left side, mity, affecting between 5.5% and 19.4% of the population.1 Early without any sign or symptom of temporomandibular joint disorders.