Boethius the Demiurge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster

The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster v. 12.11, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 29 June 2018 Page 1 of 25 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES THE CHALDEAN ORACLES OF ZOROASTER Contents A brief note about the Chaldeans. 3 Cause God, Father, Mind, Fire Monad, Duad, Triad. 4 Ideas Intelligibles, Intellectuals, Iynges, Synoches, Teletarchæ, Fountains, Principles, Hecate, and Dæmons. 8 Particular Souls Soul, Life, Man. 13 Matter Matter, the Word, and Nature. 16 Magical and Philosophical Precepts [For would-be disciples] 20 The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster v. 12.11, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 29 June 2018 Page 2 of 25 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES THE CHALDEAN ORACLES OF ZOROASTER A brief note about the Chaldeans. These “mysterious” Akkadians or Chaldeans, whose name both upon classical and biblical authority designates not only a nation but that peculiar priestly caste initiat- ed in and entirely devoted to the Sciences of astrology and magic. Held sacred in all ages, this peculiar learning was concentrated in Babylon and known in the remotest periods of history as a system of religious worship and Science which made the glory of the Chaldean.1 [The Chaldeans] assuredly got their primitive learning from the Brahmans, for H.C. Rawlinson shows an undeniably Vedic influence in the early mythology of Babylon; and Col. Vans Kennedy has long since justly declared that Babylonia was, from her origin, the seat of Sanskrit and Brahman learning.2 . [H]Ea, the God of Wisdom, [is] now identified with the Ōannēs of Berosus, the half-man, half-fish, who taught the Babylonians culture and the art of writing.3 It is maintained that INDIA (not in its present limits, but including its ancient bound- aries) is the only country in the world which still has among her sons adepts, who have the knowledge of all the seven sub-systems and the key to the entire system. -

On the Chaldaean Oracles 565

Classical Quarterly 56.2 563–581 (2006) Printed in Great Britain 563 doi:10.1017/S0009838806000541 A NEGLECTED TESTIMONIUM ON THECHALDAEAN ORACLESG. BECHTLE A NEGLECTED TESTIMONIUM (FRAGMENT?) ON THE CHALDAEAN ORACLES* INTRODUCTION The Chaldaean Oracles, their Platonic context and their influence on later Platonism have recently received fresh scholarly attention (from, for example, Polymnia Athanassiadi, Carine van Liefferinge and Ruth Majercik).1 But although an important quotation from the Oracles—in indirect speech—can be found in the anonymous Turin Commentary on the Platonic Parmenides (9.1–8), this latter does not seem to have received a great deal of attention in the scholarly literature on the Oracles.2 Thus it seems that the Commentary’s importance with respect to the Oracles is either not fully realized or else undervalued. Probably because the piece of text is a non-literal, that is, non-metric, quotation, editors of the Chaldaean Oracles have rejected the notion that it constitutes an actual fragment, and have viewed it only as a testimonium or a text of reference.3 However, it will be argued that what we actually * I would like to thank the Swiss National Science Foundation for generously supporting my work on this article. I also owe a debt of gratitude to both the anonymous referee and Luc Brisson for their valuable comments. 1 P. Athanassiadi, ‘The Chaldaean Oracles: theology and theurgy’, in P. Athanassiadi and M. Frede (edd.), Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (Oxford, 1999), 149–83. C. van Liefferinge, La Théurgie. Des Oracles Chaldaïques àProclus, Kernos supplément 9 (Liège, 1999). R. -

Friedrich Klingner – L'epos Di Catullo Su Peleo

Friedrich Klingner – L’epos di Catullo su Peleo DICTI STVDIOSVS CLASSICI DELLA FILOLOGIA IN TRADUZIONE serie diretta da Lucio Cristante e Marco Fernandelli – 3 – L’epos di Catullo su Peleo / Friedrich Klingner ; traduzione italiana di Chiara Maria Bieker con un saggio introduttivo di Marco Fernandelli. — Trieste : EUT, 2016. C, 94 p. ; 21 cm. (Dicti studiosus : classici della filologia in traduzione ; n. 3) ISBN 978-88-8303-801-3 (print) ISBN 978-88-8303-802-0 (online) I. Bieker, Chiara Maria II. Fernandelli, Marco 871.01 (ed. 22) POESIA LATINA, ORIGINI-499 CATULLO, GAIO VALERIO . CARME 64 Edizione originale Catulls Peleus-Epos in Studien zur griechischen und römischen Literatur, Zürich und Stuttgart, Artemis-Verlag © Copyright 1964 Artemis-Verlag, Zürich und Stuttgart. © Copyright 2016 by EUT Trieste. ISBN 978-88-8303-801-3 (print) ISBN 978-88-8303-802-0 (online) EUT - Edizioni Università di Trieste via E. Weiss, 21 - 34128 Trieste http://eut.units.it FRIEDRICH KLINGNER L’epos di Catullo su Peleo Traduzione italiana di Chiara Maria Bieker Con un saggio introduttivo di Marco Fernandelli Edizione a cura di Marco Fernandelli EUT Trieste 2016 SOMMARIO Friedrich Klingner e la filologia classica tedesca (M. Fernandelli) IX I. Lineamenti di una biografia intellettuale IX II. Antichità reale e ideale XXVII III. Catulls Peleus-Epos LVIII IV. La critica catulliana prima e dopo Klingner LXXII Riferimenti bibliografici LXXXI Nota del curatore dell’edizione italiana XCIX L’epos di Catullo su Peleo 1 I. L’inizio del carme 1 II. Peleo 7 III. Arianna 24 1. Arianna abbandonata e salvata: la tradizione e i motivi catulliani 24 2. -

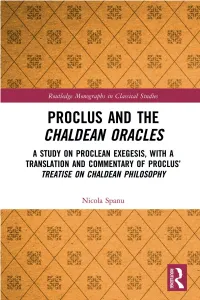

Proclus and the Chaldean Oracles

Proclus and the Chaldean Oracles This volume examines the discussion of the Chaldean Oracles in the work of Proclus, as well as offering a translation and commentary of Proclus’ Treatise On Chaldean Philosophy . Spanu assesses whether Proclus’ exegesis of the Chaldean Oracles can be used by modern research to better clarify the content of Chaldean doctrine or must instead be abandoned because it represents a substantial misinterpretation of originary Chaldean teachings.The volume is augmented by Proclus’ Greek text, with English translation and commentary. Proclus and the Chaldean Oracles will be of interest to researchers working on Neoplatonism, Proclus and theurgy in the ancient world. Nicola Spanu wrote a PhD thesis on Plotinus and his Gnostic disciples and took part in a postdoctoral project on Byzantine cosmology and its relation to Neoplatonism. He has worked as an independent researcher on his second academic publication, which has focused on Proclus and the Chaldean Oracles. Routledge Monographs in Classical Studies Titles include : Un-Roman Sex Gender, Sexuality, and Lovemaking in the Roman Provinces and Frontiers Edited by Tatiana Ivleva and Rob Collins Robert E. Sherwood and the Classical Tradition The Muses in America Robert J. Rabel Text and Intertext in Greek Epic and Drama Essays in Honor of Margalit Finkelberg Edited by Jonathan Price and Rachel Zelnick-Abramovitz Animals in Ancient Greek Religion Edited by Julia Kindt Classicising Crisis The Modern Age of Revolutions and the Greco-Roman Repertoire Edited by Barbara Goff and Michael Simpson Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka Proclus and the Chaldean Oracles A Study on Proclean Exegesis , with a Translation and Commentary of Proclus’ Treatise On Chaldean Philosophy Nicola Spanu Greek and Roman Military Manuals Genre and History Edited by James T. -

A Mathematician Reads Plutarch: Plato's Criticism of Geometers of His Time

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Claremont Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 7 | Issue 2 July 2017 A Mathematician Reads Plutarch: Plato's Criticism of Geometers of His Time John B. Little College of the Holy Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Little, J. B. "A Mathematician Reads Plutarch: Plato's Criticism of Geometers of His Time," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 7 Issue 2 (July 2017), pages 269-293. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.201702.13 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol7/iss2/13 ©2017 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. A Mathematician Reads Plutarch: Plato's Criticism of Geometers of His Time Cover Page Footnote This essay originated as an assignment for Professor Thomas Martin's Plutarch seminar at Holy Cross in Fall 2016. -

A Short History of Greek Mathematics

Cambridge Library Co ll e C t i o n Books of enduring scholarly value Classics From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, Latin and Greek were compulsory subjects in almost all European universities, and most early modern scholars published their research and conducted international correspondence in Latin. Latin had continued in use in Western Europe long after the fall of the Roman empire as the lingua franca of the educated classes and of law, diplomacy, religion and university teaching. The flight of Greek scholars to the West after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 gave impetus to the study of ancient Greek literature and the Greek New Testament. Eventually, just as nineteenth-century reforms of university curricula were beginning to erode this ascendancy, developments in textual criticism and linguistic analysis, and new ways of studying ancient societies, especially archaeology, led to renewed enthusiasm for the Classics. This collection offers works of criticism, interpretation and synthesis by the outstanding scholars of the nineteenth century. A Short History of Greek Mathematics James Gow’s Short History of Greek Mathematics (1884) provided the first full account of the subject available in English, and it today remains a clear and thorough guide to early arithmetic and geometry. Beginning with the origins of the numerical system and proceeding through the theorems of Pythagoras, Euclid, Archimedes and many others, the Short History offers in-depth analysis and useful translations of individual texts as well as a broad historical overview of the development of mathematics. Parts I and II concern Greek arithmetic, including the origin of alphabetic numerals and the nomenclature for operations; Part III constitutes a complete history of Greek geometry, from its earliest precursors in Egypt and Babylon through to the innovations of the Ionic, Sophistic, and Academic schools and their followers. -

5. Hipparchus 6. Ptolemy

introduction | 15 catalogue included into his oeuvre? Our answer is in Hipparchus. The catalogue itself has not survived. the positive. We have developed a method to serve However, it is believed that the ecliptic longitude and this end, tested it on several veraciously dated cata- latitude of each star was indicated there, as well as the logues, and then applied it to the Almagest. The reader magnitude. It is believed that Hipparchus localised the shall find out about our results in the present book. stars using the same terms as the Almagest: “the star Let us now cite some brief biographical data con- on the right shoulder of Perseus”,“the star over the cerning the astronomers whose activities are imme- head of Aquarius” etc ([395], page 52). diately associated with the problem as described above. One invariably ponders the extreme vagueness of These data are published in Scaligerian textbooks. One this star localization method. Not only does it imply must treat them critically, seeing as how the Scaligerian a canonical system of drawing the constellations and version of history is based on an erroneous chronol- indicating the stars they include – another stipulation ogy (see Chron1 and Chron2). We shall consider is that there are enough identical copies of a single star other facts that confirm it in the present book. chart in existence. This is the only way to make the verbal descriptions of stars such as the above work 5. and help a researcher with the actual identification of HIPPARCHUS stars. However, in this case the epoch of the cata- logue’s propagation must postdate the invention of Scaligerian history is of the opinion that astron- the printing press and the engraving technique, since omy became a natural science owing to the works of no multiple identical copies of a single work could be Hipparchus, an astronomer from the “ancient” Greece manufactured earlier. -

Pattison, Kirsty Laura (2020) Ideas of Spiritual Ascent and Theurgy from the Ancients to Ficino and Pico. Mth(R) Thesis

Pattison, Kirsty Laura (2020) Ideas of spiritual ascent and theurgy from the ancients to Ficino and Pico. MTh(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81873/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Ideas of Spiritual Ascent and Theurgy from the Ancients to Ficino and Pico Kirsty Laura Pattison MA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MTh (by Research). School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow Supervisors Prof Charlotte Methuen Dr Mia Spiro October 2020 Declaration of Originality Form – Research Degrees This form must be completed and signed and submitted with your thesis. Name Kirsty Laura Pattison ............................................................................................................. Student Number ........................................................................................................... Title of degree MTh (by Research) .................................................................................................. Title of thesis Ideas of Spiritual Ascent from the Ancients to Ficino and Pico .................................. The University's degrees and other academic awards are given in recognition of a student's personal achievement. All work submitted for assessment is accepted on the understanding that it is the student's own effort. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook #31061: a History of Mathematics

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of Mathematics, by Florian Cajori This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A History of Mathematics Author: Florian Cajori Release Date: January 24, 2010 [EBook #31061] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS *** Produced by Andrew D. Hwang, Peter Vachuska, Carl Hudkins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net transcriber's note Figures may have been moved with respect to the surrounding text. Minor typographical corrections and presentational changes have been made without comment. This PDF file is formatted for screen viewing, but may be easily formatted for printing. Please consult the preamble of the LATEX source file for instructions. A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS BY FLORIAN CAJORI, Ph.D. Formerly Professor of Applied Mathematics in the Tulane University of Louisiana; now Professor of Physics in Colorado College \I am sure that no subject loses more than mathematics by any attempt to dissociate it from its history."|J. W. L. Glaisher New York THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1909 All rights reserved Copyright, 1893, By MACMILLAN AND CO. Set up and electrotyped January, 1894. Reprinted March, 1895; October, 1897; November, 1901; January, 1906; July, 1909. Norwood Pre&: J. S. Cushing & Co.|Berwick & Smith. -

The Ears of Hermes

The Ears of Hermes The Ears of Hermes Communication, Images, and Identity in the Classical World Maurizio Bettini Translated by William Michael Short THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRess • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2000 Giulio Einaudi editore S.p.A. All rights reserved. English translation published 2011 by The Ohio State University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bettini, Maurizio. [Le orecchie di Hermes. English.] The ears of Hermes : communication, images, and identity in the classical world / Maurizio Bettini ; translated by William Michael Short. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1170-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1170-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9271-6 (cd-rom) 1. Classical literature—History and criticism. 2. Literature and anthropology—Greece. 3. Literature and anthropology—Rome. 4. Hermes (Greek deity) in literature. I. Short, William Michael, 1977– II. Title. PA3009.B4813 2011 937—dc23 2011015908 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1170-0) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9271-6) Cover design by AuthorSupport.com Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Translator’s Preface vii Author’s Preface and Acknowledgments xi Part 1. Mythology Chapter 1 Hermes’ Ears: Places and Symbols of Communication in Ancient Culture 3 Chapter 2 Brutus the Fool 40 Part 2. -

Cellini's Perseus and Medusa: Configurations of the Body

CELLINI’S PERSEUS AND MEDUSA: CONFIGURATIONS OF THE BODY OF STATE by CHRISTINE CORRETTI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Professor Edward J. Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Christine Corretti candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree.* (signed) Professor Edward J. Olszewski (chair of the committee) Professor Anne Helmreich Professor Holly Witchey Dr. Jon S. Seydl (date) November, 2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 Copyright © 2011 by Christine Corretti All rights reserved 2 Table of Contents List of Illustrations 4 Abstract 9 Introduction 11 Chapter 1 The Story of Perseus and Medusa, an Interpretation 28 of its Meaning, and the Topos of Decapitation Chapter 2 Cellini’s Perseus and Medusa: the Paradigm of Control 56 Chapter 3 Renaissance Political Theory and Paradoxes of 100 Power Chapter 4 The Goddess as Other and Same 149 Chapter 5 The Sexual Symbolism of the Perseus and Medusa 164 Chapter 6 The Public Face of Justice 173 Chapter 7 Classical and Grotesque Polities 201 Chapter 8 Eleonora di Toledo and the Image of the Mother 217 Goddess Conclusion 239 Illustrations 243 Bibliography 304 3 List of Illustrations Fig. 1 Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus and Medusa, 1545-1555, 243 Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy. Fig. 2 Donatello, Judith and Holofernes, c. 1446-1460s, Palazzo 244 Vecchio, Florence, Italy. Fig. 3 Heracles killing an Amazon, red figure vase. -

Illinois Classical Studies, Volume I

r m LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 880 v.l Classics The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN DEC la 76 199^ hwvi (JCTl2«n Mil TO JUL 08 1938 SFP 1 3 19 '9 mi 1 4 15'^1), ^JUL s 5 ^f FES 2 i U84 JAIIZ2 m 3 1939 L161 — O-1096 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES, VOLUME I ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME I 1976 Miroslav Marcovich, Editor UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana Chicago London [976 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN: 0-252-00516-3 •r or CLASSICS Preface Illinois Classical Studies (ICS) is a serial publication of the Classics Depart- ments of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Chicago Circle which contains the results of original research dealing with classical antiquity and with its impact upon Western culture. ICS welcomes scholarly contributions dealing with any topic or aspect of Greek and/or Roman literature, language, history, art, culture, philosophy, religion, and the like, as well as with their transmission from antiquity through Byzantium or Western Europe to our time. ICS is not limited to contributions coming from Illinois. It is open to classicists of any flag or school of thought. In fact, of sixteen contributors to Volume I (1976), six are from Urbana, two from Chicago, six from the rest of the country, and two from Europe.