Journal of Law V6n1 2016-7-28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

Mystery on Baker Street

MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET BRUTAL KAZAKH OFFICIAL LINKED TO £147M LONDON PROPERTY EMPIRE Big chunks of Baker Street are owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money-laundering. JULY 2015 1 MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET Brutal Kazakh official linked to £147m London property empire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The ability to hide and spend suspect cash overseas is a large part of what makes serious corruption and organised crime attractive. After all, it is difficult to stuff millions under a mattress. You need to be able to squirrel the money away in the international financial system, and then find somewhere nice to spend it. Increasingly, London’s high-end property market seems to be one of the go-to destinations to give questionable funds a veneer of respectability. It offers lawyers who sell secrecy for a living, banks who ask few questions, top private schools for your children and a glamorous lifestyle on your doorstep. Throw in easy access to anonymously-owned offshore companies to hide your identity and the source of your funds and it is easy to see why Rakhat Aliyev. (Credit: SHAMIL ZHUMATOV/X00499/Reuters/Corbis) London’s financial system is so attractive to those with something to hide. Global Witness’ investigations reveal numerous links This briefing uncovers a troubling example of how between Rakhat Aliyev, Nurali Aliyev, and high-end London can be used by anyone wanting to hide London property. The majority of this property their identity behind complex networks of companies surrounds one of the city’s most famous addresses, and properties. -

His Last Bow Online

NPa3J (Mobile pdf) His Last Bow Online [NPa3J.ebook] His Last Bow Pdf Free Arthur Conan Doyle ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 2016-04-11 2016-04-11File Name: B01E4S1688 | File size: 33.Mb Arthur Conan Doyle : His Last Bow before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised His Last Bow: His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes is a collection of seven previously-published Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. Five of the stories were published in The Strand Magazine between September 1908 and December 1913. The final story, an epilogue about Holmes' war service, was first published in Collier's on 22 September 1917mdash;one month before the book's premier on 22 October. Some later editions of the collection include "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box", which was also collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894). The Strand published "The Adventure of Wistaria Lodge" as "A Reminiscence of Sherlock Holmes", and divided it into two parts, called "The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles" and "The Tiger of San Pedro". Later printings of His Last Bow correct Wistaria to Wisteria. Also, the first US edition adjusts the subtitle to Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. All editions contain a brief preface, by "John H. Watson, M.D.". The preface assures readers that as of the date of publication (1917), Holmes is long retired from his profession of detectivemdash;but is still alive and well, albeit suffering from a touch of rheumatism. -

Stephen Tolins, M.D., B.S.I., U.S.N. I by John Linsenmeyev; B.S.I

June 2003 Volume 7 Number 2 II 111 I/ Sk srlock Holz~es 3ur merits should be publicly recognize STUD) 1'11ni 1, 11 Contents Stephen Tolins, M.D., B.S.I., U.S.N. I By John Linsenmeyev; B.S.I. I tephen Tolins, !I 1 tephen H. Tolins, M.D., U.S.N. (Ret.), B.S.I. died at the age of 89 on February 24, 2003. For many Sherlockians, he was known as the author of Sherlockian Twaddle. He was the quizmaster and loyal friend of the Three Garridebs of Westchester, and - to his wife and fa HolmesS and his alma mater, Cornell University. I ! 100 Years Ago , ,* ,,> , ,,, ,!,I'll+ "' ipl:!,,' I.' 1,,1. ' .! I,II, IIK,,,,, pl/ii;41:,j,,14 II~ , ,t ,2 Steve wrote "In the year 1938 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Cornell," and completed studies to become a board-certified gener- al surgeon. He was called to serve his country as a Navy surgeon on December 8, 1941 and his accom- I ,'. the President plishments included setting up a hospital in ,G ::, , ,#,',,,,,,, li l~!'Y~'ii I? Northern Ireland to care for casualties in the Atlantic theater of war. At the conclusion of World War 11, 0, ?I.?, : ;., '.j!,! e ;i. ./.I 1, he was training with the Marine Corps for the , . lsl,'i. I ihi. ,lI';;/ , ~~~in~s planned invasion of Japan. Dr. Tolins remained a ,a :i~lll~~~ilI:,); rG4/: bll~8f:illlb 4 Navy physician throughout the Korean War and " I: 'JY8l!11, llItl ii,s,i ,,II'<I~3 !I.,, eventually turned to teaching surgical residents in Using the Collections Navy hospitals. -

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Date Event Notes

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Parties: British Land, McAleer & Rushe. Bank of Ireland, NAMA, Portman Estate Topic: 2-14 Baker Street - in London which was subject to a loan from Bank of Ireland Timeline: Date Event Notes August Several media articles report on This was the second reported purchase by and agreement between British Land and McAleer & Rushe from British Land – the September McAleer & Rushe for the sale (by BL) previous deal was for the Swiss Centre in 2005 of 2-14 Baker Street. Leicester Square. Guide price for the 2-14 Baker Street property was UK£47.5m with British Land offering it as a potential 150,000 sq. ft development opportunity. 5th 2-14 Baker Street purchased by Travers Smith acted for McAleer & Rushe October McAleer & Rushe by British Land for Group on the acquisition. 2005 UK£57.2m. The existing building tenants: Purchase funded with a Bank of Offices let on a lease expiring in December Ireland loan. 2009. Retail accommodation let under four separate leases all expiring by December 2009 The property comprised 94,000 sq. ft. held on a 98 year headlease from the Portman Estate. 16th Planning Application submitted to Planning application filed by Gerald Eve, December Westminster City Council listing Chartered Surveyors and Property Consultants 2008 Owners pf 2-14 Baker Street as: Contact person: James Owens 1. Portman Estate (freeholder) [email protected] 2. Mourant & Co Trustees Ltd and Mourant Property Trustees Ltd Baker Street Unit Trust is owned by McAleer & as Trustees of the Baker Street Rushe with a Jersey address. -

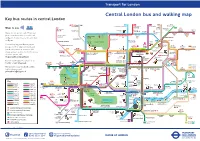

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Kathryn Morrison, ‘Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 281–308 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 BAZAARS AND BAZAAR BUILDINGS IN REGENCY AND VICTORIAN LONDON KATHRYN A MORRISON INTRODUCTION upper- and middle-class shoppers, they developed ew retail or social historians have researched the the concept of browsing, revelled in display, and Flarge-scale commercial enterprises of the first discovered increasingly inventive and theatrical ways half of the nineteenth century with the same of combining shopping with entertainment. In enthusiasm and depth of analysis that is applied to the devising the ideal setting for this novel shopping department store, a retail format which blossomed in experience they pioneered a form of retail building the second half of the century. This is largely because which provided abundant space and light. Th is type copious documentation and extensive literary of building, admirably suited to a sales system references enable historians to use the department dependent on the exhibition of goods, would find its store – and especially the metropolitan department ultimate expression in department stores such as the store – to explore a broad range of social, economic famous Galeries Lafayette in Paris and Whiteley’s in and gender-specific issues. These include kleptomania, London. labour conditions, and the development of shopping as a leisure activity for upper- and middle-class women. Historical sources relating to early nineteenth- THE PRINCIPLES OF BAZAAR RETAILING century shopping may be relatively sparse and Shortly after the conclusion of the French wars, inaccessible, yet the study of retail innovation in that London acquired its first arcade (Royal Opera period, both in the appearance of shops and stores Arcade) and its first bazaar (Soho Bazaar), providing and in their economic practices, has great potential. -

139 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

139 bus time schedule & line map 139 Waterloo - Golders Green View In Website Mode The 139 bus line (Waterloo - Golders Green) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Golders Green: 24 hours (2) Waterloo: 24 hours Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 139 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 139 bus arriving. Direction: Golders Green 139 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Golders Green Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 24 hours Monday 24 hours Waterloo Station / Tenison Way (J) Whichcote Street, London Tuesday 24 hours Waterloo Bridge / South Bank (P) Wednesday 24 hours 1 Charlie Chaplin Walk, London Thursday 24 hours Lancaster Place (T) Friday 24 hours Lancaster Place, London Saturday 24 hours Savoy Street (U) 105-108 Strand, London Bedford Street (J) 60-64 Strand, London 139 bus Info Direction: Golders Green Charing Cross Station (H) Stops: 42 Duncannon Street, London Trip Duration: 62 min Line Summary: Waterloo Station / Tenison Way (J), Trafalgar Square (T) Waterloo Bridge / South Bank (P), Lancaster Place Cockspur Street, London (T), Savoy Street (U), Bedford Street (J), Charing Cross Station (H), Trafalgar Square (T), Regent Regent Street / St James's (Z) Street / St James's (Z), Piccadilly Circus (E), Beak 11 Lower Regent Street, London Street / Hamleys Toy Store (L), Oxford Street / John Lewis (OR), Selfridges (BX), Orchard Street / Piccadilly Circus (E) Selfridges (BA), Portman Square (Y), York Street (F), 83-97 Regent Street, London Baker Street Station (C), Park Road/ Ivor Place (X), -

Bhattacharya, Laboni-3

Lapis Lazuli UGC APPROVED, BLIND PEER-REVIEWED An International Literary Journal ISSN 2249-4529 WWW.PINTERSOCIETY.COM VOL.7 / NO.1/ SPRING 2017 Plotting, Print and Responses to Popular Culture: The Beginnings of the Sherlock Holmes Fandom in the Nineteenth Century Laboni Bhattacharya ABSTRACT: This paper posits a possible socio-literary moment in the emergence of the category of the ‘fan’, especially the fan of detective fiction in 19th century England. A convergence of factors, this paper would argue, both textual and material, shaped this emergence. In 19th century England, for the first time, technology in the form of popular print culture facilitated a popular surge of interest in the genre of detective fiction, which was sustained through certain technologies of the text. The textual and formal peculiarities of the detective story – the exploitation of narrative desire through ‘plotting’ (Brooks, 1984; Rzepka, 2005, 2010), the figure of the ‘Morellising’ (Ginzburg, 2003) detective himself – created a hyper-engaged reader in the image of the form itself: detail-oriented and intellectually competitive. At the same time, the material conditions of serialised print fiction allowed readers to 45 Lapis Lazuli An International Literary Journal ISSN 2249-4529 participate in ‘imagined communities’ (Anderson, 2006) as they became aware of the existence of other readers due to the materiality of magazine circulation and subscriptions. These communities of dedicated fans consolidated themselves into what contemporary scholars call a fandom 1 , further sustaining the exegetical reading practices and accretion of trivia that separates the fan from the ordinary reader. This paper is a brief attempt at charting the rise in the simultaneous creation of the fan and the rise of the Sherlock Holmes ‘fandom’ in the 19th century as a confluence of the textual technology of narrative and the material technology of print culture. -

9 8 Baker Street

98 BAKER STREET a development by Marylebone has emerged as a vibrant and trendy location, nestled A VIBRANT away from the hustle and bustle of the daily city rush. It offers a truly unique experience, combining the relaxed pace and serenity of VILLAGE IN THE village life, with an address in the heart of Central London HEART OF LONDON 98 Baker Street is an elegant 5 storey building, with a stunning traditional brick facade which pays homage to classic British architecture and houses 8 premium apartments comprising a mix of one, two and three bedroom apartments, including a spectacular top floor penthouse. It is is mere moments away from a host of London’s most iconic landmarks such as Harrods, Buckingham Palace, Mayfair and Westminster. Named after builder William Baker, Baker Street originated in the 8th Century as an affluent area within the Borough of Westminster. The area originally consisted of luxury housing for wealthy residents and developed a reputation as one of the swankiest and trendiest residential districts within London. The street itself is over 1.5 km long and connects Marylebone to Oxford Street, making it one of the main arteries within the West End. 2 3 AN EXCEPTIONAL LOCATION Owning an address on Baker Street is to enjoy the best of both worlds: a bright, diverse and well-connected Central London location combined with convenient access to a wealth of open, green spaces. Marylebone has all the distinctive flavours of a quaint, CAMDEN MARKET modern village, surrounded by pedestrian streets, glorious greenery, boutique stores and craft eateries.