Report by the Consumption Tax Technical Advisory Group (Tag)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxation Paradigms: JOHN WEBB SUBMISSION APRIL 2009

Taxation Paradigms: What is the East Anglian Perception? JOHN WEBB A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SUBMISSION APRIL 2009 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY What we calf t[ie beginningis oftenthe end And to makean endis to makea beginning ?fie endis wherewe start ++++++++++++++++++ Weshall not ceasefrom exploration And the of exploring end .. Wilt to arrivewhere we started +++++++++++++++++ 7.S f: Cwt(1974,208: 209) ? fie Four Quartets,Coffected Poems, 1909-1962 London: Faderand Fader 2 Acknowledgements The path of a part time PhD is long and at times painful and is only achievablewith the continued support of family, friends and colleagues. There is only one place to start and that is my immediate family; my wife, Libby, and daughter Amy, have shown incredible patienceover the last few years and deserve my earnest thanks and admiration for their fantastic support. It is far too easy to defer researchwhilst there is pressingand important targets to be met at work. My Dean of Faculty and Head of Department have shown consistent support and, in particular over the last year my workload has been managedto allow completion. Particularthanks are reservedfor the most patientand supportiveperson - my supervisor ProfessorPhilip Hardwick.I am sure I am one of many researcherswho would not have completed without Philip - thank you. ABSTRACT Ever since the Peasant'sRevolt in 1379, collection of our taxes has been unpopular. In particular when the taxes are viewed as unfair the population have reacted in significant and even violent ways. For example the Hearth Tax of 1662, Window Tax of 1747 and the Poll tax of the 1990's have experiencedpublic rejection of these levies. -

Keys to Understanding and Utilizing the Federal and California Research Tax Credits

UPDATE ON E-COMMERCE TAXATION: FOCUS ON EVENTS OF THE PAST YEAR April 2001 Annette Nellen, CPA, Esq. Graduate Tax Program San José State University http://www.cob.sjsu.edu/facstaff/nellen_a/ WEB SITE FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ON E-COMMERCE TAXATION + LINKS http://www.cob.sjsu.edu/facstaff/nellen_a/e-links.html WHY TAX ISSUES EXIST “E-commerce represents a new business model. As such, it creates some challenges to tax systems that were designed with a different model in mind. Two key reasons help explain why e-commerce raises tax issues: 1. Location—Existing tax systems tend to determine tax consequences based on where the taxpayer is physically located. The e-commerce model enables businesses to operate with very few physical locations. 2. Nature of products—E-commerce allows for some types of products, such as newspapers and music CDs, to be delivered in digitized (intangible) form, rather than in tangible form. Digitized products may not be subject to sales tax in some states. Also, the ability to deliver digitized products, as well as services over the Internet also reduces the need for physical locations, thus creating fewer taxing points.”1 See Appendix A for additional reasons why e-commerce raises tax issues for both taxpayers and taxing authorities. THE COSTS OF E-COMMERCE TAXATION ISSUES A. State and Local Government E-commerce is in its infancy because it represents less than 1% of retail sales. Also, less than 3% of the world's population is on-line. But, the growth potential is great. The Department of Commerce projects that e-commerce will grow to hundreds of billions of dollars annually. -

SUMMER 2021 Tax Compliance Software Category

SUMMER 2021 Customer Success Report Tax Compliance Software Category Tax Compliance Software Category Tax compliance software gives you accurate federal and local tax computations, and automates tax filing and reporting. Top vendors present different solutions to manage specific types of transactions and their linked taxes. Sales tax compliance programs compute and process relevant taxes to be charged across jurisdictions. Further, Value-Added Tax (VAT) applications monitor regulations and automate computations across intricate scenarios. Advanced tax compliance tools support custom tax management for global sales. Many vendors also deliver managed audit reporting and tax filing for businesses of all sizes. SUMMER 2021 CUSTOMER SUCCESS REPORT Tax Compliance Software Category 2 Award Levels Customer Success Report Ranking Methodology The FeaturedCustomers Customer Success ranking is based on data from our customer reference platform, market presence, MARKET LEADER web presence, & social presence as well as additional data Vendor on FeaturedCustomers.com with aggregated from online sources and media properties. Our substantial customer base & market ranking engine applies an algorithm to all data collected to share. Leaders have the highest ratio of calculate the final Customer Success Report rankings. customer success content, content quality score, and social media presence The overall Customer Success ranking is a weighted average relative to company size. based on 3 parts: CONTENT SCORE ● Total # of vendor generated customer references (case studies, success stories, testimonials, and customer videos) ● Customer reference rating score TOP PERFORMER ● Year-over-year change in amount of customer references on Vendor on FeaturedCustomers.com with FeaturedCustomers platform significant market presence and ● Total # of profile views on FeaturedCustomers platform resources and enough customer ● Total # of customer reference views on FeaturedCustomers reference content to validate their vision. -

Office of CFO Market Map: Tax Management Software January 2021 Agenda

Office of CFO Market Map: Tax Management Software January 2021 Agenda Shea & Company Overview Office of the CFO Market Overview Market Activity 1 Shea & Company Overview About Our Firm 1 2 29 $10Bn+ 15+ 100+ Firm focused exclusively on Offices in Boston and San Professionals focused on the Advised transaction value in Average years of experience Transactions completed enterprise software Francisco software industry last 12 months amongst our senior bankers representing billions of dollars in value Mergers & Acquisitions, Private Placements & Capital Raising Shea & Company has advised on important transactions representing billions of dollars in value across the strategic acquirer and financial investor landscape with Clients in the U.S. as well as Canada, Europe and Israel. has received a majority investment has received an investment from has been acquired by has received an investment from has made a majority investment in has received an investment from has acquired from Public Sector & Healthcare has been acquired by has received an investment from has been acquired by has been acquired by have been merged with has acquired has acquired has acquired has been acquired by has received an investment from has received an investment from has been acquired by has received an investment from has been acquired by 2 Shea & Company Overview Case Study: HgCapital’s Acquisition of Sovos Compliance Transaction Profile Sovos Profile HGCapital Profile In March 2016, HgCapital announced a majority investment in Sovos is a leading provider of regulatory -

GREEN PASSPORT Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘I

GREEN PASSPORT Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘i Improving the visitor experience and protecting Hawai‘i’s natural heritage © Pascal Debrunner Purpose: The purpose of this report is to identify and explore innovative conservation finance solutions that bring additional revenue to support conservation in Hawai‘i and effectively manage cultural and natural resources that are critical to our communities’ wellbeing and the visitor experience. Scope of Work: (1) This report reviews existing visitor green fee programs that support conservation in jurisdictions around the world. (2) Based on this information, the report then explores legal, economic, and political considerations in Hawai‘i that shape the implementation of a potential visitor green fee program for the State of Hawai‘i. (3) Lastly, the report presents potential pathways for a visitor green fee in Hawai‘i, noting that each of these options require further legal and policy research. How to cite: von Saltza, E. 2019. Green Passport: Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘i. A report prepared for Conservation International. Acknowledgements: The report was developed with the support of The Harold K.L. Castle Foundation, Hawai‘i Leadership Forum, and The Nature Conservancy. We are thankful for insights and perspectives from a wide range of thought leaders across the visitor and conservation sectors. October 2019 © Photo Rodolphe Holler TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................ -

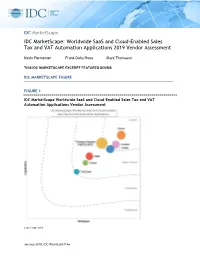

IDC Marketscape: Worldwide Saas and Cloud-Enabled Sales Tax and VAT Automation Applications 2019 Vendor Assessment

IDC MarketScape IDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Sales Tax and VAT Automation Applications 2019 Vendor Assessment Kevin Permenter Frank Della Rosa Mark Thomason THIS IDC MARKETSCAPE EXCERPT FEATURES SOVOS IDC MARKETSCAPE FIGURE FIGURE 1 IDC MarketScape Worldwide SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Sales Tax and VAT Automation Applications Vendor Assessment Source: IDC, 2019 January 2019, IDC #US43263718e Please see the Appendix for detailed methodology, market definition, and scoring criteria. IN THIS EXCERPT The content for this excerpt was taken directly from IDC MarketScape: Worldwide SaaS and Cloud- Enabled Sales Tax and VAT Automation Applications 2019 Vendor Assessment (Doc #US43263718). All or parts of the following sections are included in this excerpt: IDC Opinion, IDC MarketScape Vendor Inclusion Criteria, Essential Guidance, Vendor Summary Profile, Appendix and Learn More. Also included is Figure 1. IDC OPINION Digital Transformation Driving Change Digital transformation (DX) is fundamentally changing financial applications, allowing businesses to transform their decision making, which is enhancing their business outcomes significantly in the digital economy. Digital transformation is an enterprise wide, board-level, strategic reality for companies wishing to remain relevant or maintain or enhance their leadership position in the digital economy. Digitally transformed businesses have a repeatable set of practices and disciplines used to leverage new business, 3rd Platform technology, and operating models to disrupt businesses, customers, and markets in pursuit of business performance and growth. DX is driving businesses to rethink their technology strategy and that includes moving beyond their legacy finance and back-office systems. SaaS and Cloud-Enabled Software Driving Investment Instead of continuing to invest in antiquated on-premises systems, leading DX businesses have turned their focus to SaaS and cloud-enabled software because they need flexible and agile financial applications that are relatively easy to implement, configure, and update. -

Orbitax Essential International Tax Solutions

REUTERS/Jo Yong-Hak ORBITAX ESSENTIAL INTERNATIONAL TAX SOLUTIONS ALIGN AND STREAMLINE YOUR TAX PLANNING WORKFLOW FOR CROSS-BORDER TRANSACTIONS ACROSS MULTINATIONAL ENTITIES ALIGN YOUR GLOBAL TAX UNIVERSE The universe of global tax is intricate and constantly shifting. Staying on top of these shifting changes around the globe is a challenge, but is absolutely critical to the management and compliance of your organization. Orbitax Essential International Tax Solutions on Checkpoint World is the comprehensive dashboard that aligns your tax planning needs across all of your global businesses. With its extensive and powerful research and analysis tools, you’ll be able to complete your global tax requirements efficiently and develop business strategies that align with ever-changing and complicated compliance regulations. 2 ORBITAX ESSENTIAL INTERNATIONAL TAX SOLUTIONS Checkpoint World and Orbitax are designed to work in alignment with each other to deliver a complete end-to-end solution for all your global tax research needs. Our Orbitax solutions will help you streamline your global cross-border tax efforts and your research workflow by minimizing cost inefficiencies, maximizing time efficiencies, and mitigating risk. ORBITAX ESSENTIAL INTERNATIONAL TAX SOLUTIONS 3 RESEARCH & PLANNING Easily navigate through the business environment and tax rules of their various entities with our comprehensive tax research, integrated with extensive planning tools that allow you to model various tax scenarios to determine the optimal tax planning strategies -

Tax Compliance Services RITZ INTERACTIVE, INC

Tax Compliance Services TAX COMPLIANCE SERVICES COMPLIANCE TAX Strategic Insight and Knowledge “RYAN’S UNCOMPROMISING ATTENTION TO DETAIL, AS WELL AS THEIR STRATEGIC INSIGHT AND EXTENSIVE KNOWLEDGE OF TAX LEGISLATION PROVIDE OUTSTANDING VALUE. THEIR PROFESSIONALS ARE RESPONSIVE, HELPFUL, AND COMMITTED TO CLIENT SERVICE EXCELLENCE.” Scott Neamand, Executive Vice President & CFO RITZ INTERACTIVE, INC. Solutions to Overcome the Key Challenges for Today’s Tax Department Tax departments are facing a new reality as they manage their organization’s transaction tax function. A perfect storm of external factors, many beyond the organization’s control, are aligning to drive a unique set of challenges for tax executives. These evolving changes present both risks and opportunities as corporate tax departments seek to manage the increased complexity of regulatory requirements such as Sarbanes-Oxley and FIN 48, as well as rapid globalization, technology and infrastructure limitations, increased risk, and a lack of resources. The increased scrutiny on tax administration from shareholders, audit committees, and management, combined with the evolving market dynamics are challenging many tax executives as they attempt to balance the increased demands of accuracy and risk mitigation against the pressure to run the department as effi ciently as possible. In a recent survey conducted by the Canadian Financial Executives Research Ryan provides a comprehensive suite of Foundation (CFERF) and CFO Research Services, an overwhelming majority of tax outsourced or co-sourced tax compliance executives reported that the primary allocations of tax department resources are services designed to meet your internal devoted to compliance, as opposed to planning. As the tax department spends Sarbanes-Oxley requirements. -

AVALARA, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-38525 AVALARA, INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its Charter) Washington 91-1995935 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 255 South King Street, Suite 1800 Seattle, WA 98104 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (206) 826-4900 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, Par Value $0.0001 Per Share AVLR New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES ☐ NO ☒ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. YES ☐ NO ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

A Survey of Tax Compliance Costs of Flemish Smes: Magnitude and Determinants

Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2011, volume 29, pages 605 ^ 621 doi:10.1068/c10177b View metadata,A survey citation ofand taxsimilar compliance papers at core.ac.uk costs of Flemish SMEs: brought to you by CORE magnitude and determinants provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Bilitis Schoonjans, Philippe Van Cauwenbergeô, Catherine Reekmans, Gudrun Simoens Department of Accountancy and Corporate Finance, Ghent University, Kuiperskaai 55/E, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 18 October 2010; in revised form 3 February 2011 Abstract. This study presents survey evidence on the magnitude and determinants of tax compliance costs in Flemish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Data were obtained from an Internet question- naire among members of a professional network of Flemish entrepreneurs, called VOKA. Analyzing a sample of 151 Flemish SMEs, we find that the tax compliance costsöexceeding over 7% of gross added valueöare relatively high. Value-added tax, labor taxes, and corporate taxes are the main components of tax compliance costs. In addition, our evidence confirms the regressivity hypothesis, according to which smaller companies face relatively higher compliance costs. Furthermore, industry, age, and the proportion of blue-collar workers prove to be determining factors of relative compliance costs. Our study concludes by formulating a number of policy recommendations that might contribute to lower compliance costs. 1 Introduction Researchers and practitioners interested in the tax burdens of companies almost exclusively focus on direct tax costs (eg, Slemrod, 2004; Vandenbussche et al, 2005). -

New Technologies and the Evolution of Tax Compliance

Tulane Economics Working Paper Series New Technologies and the Evolution of Tax Compliance James Alm Joyce Beebe Michael S. Kirsch Tulane Economics Rice University Notre Dame Law School [email protected] Omri Marian Jay A. Soled University of California Rutgers University Irvine Working Paper 2009 September 2020 Abstract Improving tax compliance is a common goal of governments worldwide. The United States is no exception. The size of the nation’s “tax gap” — or the difference between what taxpayers pay in taxes in a timely manner and what they should pay if they fully complied with the tax laws — is hundreds of billions of dollars annually, significantly depriving the nation of much-needed revenue. This paper explores the mixed effects of technological advancements on tax compliance — and, thus, its counterpart, tax noncompliance. On the one hand, technological advances have largely eradicated many of the commonplace tax-noncompliance techniques that once reigned during the twentieth century. On the other hand, many of these very same technological advances threaten to usher in new modes of tax evasion. Which of these emergent trends will dominate is unclear. The outcome will largely depend upon whether Congress updates the tax laws to address technological advances and grants sufficient funding to the Internal Revenue Service to maintain robust enforcement efforts in an ever-changing technological landscape. Failure to take these steps will destine the size of the tax gap to expand. Many prior studies have addressed discreet effects of specific technologies on tax compliance. This paper contributes to this developing literature by offering a cohesive framework to address technological advancement and tax compliance. -

Spectrum Technology Platform Version 12.0

Spectrum Technology Platform Version 12.0 Web Services Guide Table of Contents 1 - Getting Started REST 4 SOAP 27 2 - Web Services REST 51 SOAP 396 Chapter : Appendix Appendix A: Buffering 798 Appendix B: Country Codes 801 Appendix C: Validate Address Confidence Algorithm 833 1 - Getting Started In this section REST 4 SOAP 27 Getting Started REST The REST Interface Spectrum™ Technology Platform provides a REST interface to web services. User-defined web services, which are those created in Enterprise Designer, support GET and POST methods. Default services installed as part of a module only support GET. If you want to access one of these services using POST you must create a user-defined service in Enterprise Designer. To view the REST web services available on your Spectrum™ Technology Platform server, go to: http://server:port/rest Note: We recommend that you limit parameters to 2,048 characters due to URL length limits. Service Endpoints The endpoint for an XML response is: http://server:port/rest/service_name/results.xml The endpoint for a JSON response is: http://server:port/rest/service_name/results.json Endpoints for user-defined web services can be modified in Enterprise Designer to use a different URL. Note: By default Spectrum™ Technology Platform uses port 8080 for HTTP communication. Your administrator may have configured a different port. WADL URL The WADL for a Spectrum™ Technology Platform web service is: http://server:port/rest/service_name?_wadl For example: http://myserver:8080/rest/ValidateAddress?_wadl User Fields You can pass extra fields through the web service even if the web service does not use the fields.