The Case of Non-Professional Chairman, FBR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE of M.A/M.Sc./BSCS ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-I)

1 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF M.A/M.Sc./BSCS ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-I) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks Islamabad Model Postgraduate College for Girls, F-7/2, Islamabad (003) 230031410001 88001 IQRA BATOOL TANVEER AHMED COMPT. MAC-ECO 230031410002 88002 SHAFFAQ ALI SYED ALI SHAH COMPT. DEV-ECO 230031410003 88003 MEMOONA IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL COMPT. MATH-ECO MAC-ECO DEV-ECO STS-ECO 230031410004 88004 NAILA KHAN AWAL KHAN PASS 322 230031410005 88005 MARYAM SIRAJ MUHAMMAD SIRAJ PASS 283 230031410006 88006 AZMINA FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMED COMPT. MATH-ECO MAC-ECO DEV-ECO STS-ECO 230031410007 88007 ANZA KANWAL MUJAHID ALI PASS 314 230031410008 88008 RABIA IMTIAZ IMTIAZ UN NABI PASS 269 230031410009 88009 SADAF YASMEEN MUHAMMAD SHARIF PASS 243 230031410011 88010 AMBREEN BIBI MUHAMMAD GULZAR PASS 305 230031410012 88011 HAFSA FARHEEN MUHAMMAD NASEER PASS 230 230031410013 88012 AYESHA HAROON HAROON LATIF PASS 307 230031410014 88013 SIDRA TABASSUM MUHAMMAD ARSHAD PASS 275 ANJUM 230031410015 88014 IZZA KHALID KHALID RASHID COMPT. DEV-ECO STS-ECO 230031410018 88015 SHEHR BANO WASEEM AHMAD PASS 279 230031410019 88016 SAIRA ABBASI SAFEER ABBASI COMPT. MATH-ECO 230031410020 88017 RIMSHA MUNAWAR MUNAWAR HUSSAIN COMPT. MAC-ECO 230031410021 88018 SABA TAJ TAJ MUHAMMAD COMPT. MATH-ECO STS-ECO 230031410022 88019 SIDRA WALI MUHAMMAD WALI PASS 266 230031410023 88020 ZAINEB MUHAMMAD ABID COMPT. DEV-ECO STS-ECO 2 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF M.A/M.Sc./BSCS ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-I) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks 230031410025 88021 ASMAH JABEEN MAQSOOD AHMED COMPT. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

List of Gold Medal Winners

LIST OF GOLD MEDAL WINNERS FIRST POSITION IN PAKISTAN S. NO. ROLL NO. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME CLASS INSTITUTION CITY/DISTRICT FOUNDATION PUBLIC 1 19-022-00325-1-009-E AAIRA IRFAN BOZDAR IRFAN ALI BOZDAR 1 HYDERABAD SCHOOL JUNIOR SECTION ROOTS MILLENNIUM MANDI 2 19-546-20416-1-002-E ABDUL AHAD NADEEM QAMAR 1 SCHOOL RICHMOND CAMPUS BAHAUDDIN INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD 3 19-55-00925-1-001-E ABDUL HADI SHAFQAT ALI 1 GUJRANWALA SCHOOLS ALIPUR CHATTHA CAMPUS 4 19-051-20036-1-022-E ABDUL HADI KAMRAN SHABIR 1 PREPARATORY SCHOOL ISLAMABAD RANA MOHAMMAD LAHORE GRAMMAR SCHOOL 5 19-55-00811-1-005-E ABDUL HADI ADNAN 1 GUJRANWALA ADNAN SENIOR BRANCH INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC 6 19-051-00458-1-014-E ABDUL HADI AMAN AMANULLAH 1 UNIVERSITY SCHOOL I-8 ISLAMABAD CAMPUS 7 19-42-00151-1-043-E ABDUL HADI TOQEER TOQEER AFZAL 1 LAHORE GRAMMAR SCHOOL LAHORE LAHORE GRAMMAR SCHOOL 8 19-61-20706-1-061-E ABDUL HASEEB KHAN SHAHZAD ALAM KHAN 1 MULTAN JUNIOR BRANCH BEACONHOUSE SCHOOL 9 19-51-00459-1-002-E ABDUL MOEED FARHAN AHMED SHAH 1 SYSTEM EARLY YEARS AND RAWALPINDI PRIMARY BRANCH FOUNDATION PUBLIC 10 19-022-00325-1-016-E ABDUL MOIZ ZEESHAN SHAIKH 1 HYDERABAD SCHOOL JUNIOR SECTION BEACONHOUSE SCHOOL 11 19-48-20761-1-025-E ABDUL MOMIN AFZAAL AFZAAL AHMED KAUSAR 1 SARGODHA SYSTEM KG BRANCH BLOOMFIELD HALL JUNIOR DERA GHAZI 12 19-64-20555-1-004-E ABDUL RAFAY MUHAMMAD SHAKEEL 1 SCHOOL KHAN THE LYNX SCHOOL JUNIOR 13 19-051-00600-1-035-E ABDUL WAASE SAEED AHMED DHERAJ 1 ISLAMABAD SECTION THE CITY SCHOOL JUNIOR 14 19-52-20090-1-014-E ABDUL WALI AAQIB HANIF -

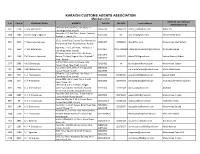

Kcaa Members List.Pdf

KARACHI CUSTOMS AGENTS ASSOCIATION Members List NAME OF AUTHORIZED S. # CHAL # COMPANY NAME ADDRESS TEL NOS FAX NOS Email Address REPRESENTATIVE Office No.614, 6th Floor, Uni Plaza, I. I. 391 2724 3- Star Enterprises 32466518 32466518 [email protected] Akbar Jan Chundrigar Road, Karachi Room No. 411, 4th Floor, Shams Chamber, 1868 2785 3a Sons Cargo Logistics 32423284 NIL [email protected] Sheikh Safdar Alam Shahrah-e-liaquat, Khi 10-11, Ayub Plaza Ground Floor Hamayoon 203 2211 7- Seas Cargo Services 32425407 32419470 [email protected] Muhammad Shahid Rafiq Muhammad Khan Road Keamari, Karachi. Room No. 713-a, Uni Plaza, 7th Floor, I. I. 495 2550 7- Star Enterprises 32412964 0213-7013682 [email protected] Dil Nawaz Ahmed Chundrigar Road, Karachi Al Saihat Centre, Suite 405, 4th Floor, 35653457- 441 1998 786 Business Syndicate Annexe To Hotel Regent Plaza, Shahrah E 35653675 [email protected] Saleem Ahmed Abbasi 35653675 Faisal, Karachi Suit No# 104, Abdullah Square, Altaf 1077 2365 A & S Enterprises 32420422 nil [email protected] Muhammad Saleem Hussain Road, New Challi, Karachi Poonawala View, Office # A-9 Opposite 32313616, 95 2986 A M S Enterprises - [email protected] Malik Allah Nawaz Custom House Karachi 32310680 Office No. 212, 2nd Floor, Uni Plaza, I. I. 983 967 A. A. Ahmad & Co 32420506 32420456 [email protected] Danish Wakil Chundrigar Road, Karachi Room #801, Jilani Tower, M. A. Jinnah 1965 924 A. A. Enterprises 32439802 32477355 [email protected] Aoun Mohammed Choudhary Road, Tower, Khi Office No.b-4 & 5, 1st Floor, Eidgah 889 2301 A. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

(Rjelal) Crime Literature a Genre in Indian Sub

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.4.Issue 4. 2016 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (Oct.Dec.) http://www.rjelal.com; Email:[email protected] RESEARCH ARTICLE CRIME LITERATURE A GENRE IN INDIAN SUB-CONTINENT & IBN-E-SAFI MUHAMMAD YASEEN1, Dr.FATEH MUHAMMAD BURFAT2 1Lecturer: English Language, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Email : [email protected] 2 Head, Department of Criminology, Faculty of Arts; University of Karachi, Pakistan Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT General consensus can be found to the origin of this special genre, although with many differences of opinion and criticism. Fundamental roots of the genre are strongly originated from European world, specifically from Britain and America. Generally crime, detective, thrill and suspense literature can be found in every culture and civilization of the world. This is also known as popular literature, which was denied as a part of literature in India and Pakistan but having a huge space MUHAMMAD YASEEN and acceptance level as a part of literature in England and America. Assured creative writers can be found in the history about the genre. The utmost popularity of the genre in Britain started with the introduction of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The devices, metaphors, level of curiosity, thrill and a mixture of mood is fabricated in such an interesting way that can shake the imaginative approach of the readers. Amongst several British and American writers the prominent impetus of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) is unique in genre. In this category of the detectives I would like to highlight separately American and British writer’s Dr.FATEH contributions to the detective genre. -

Islamabad.Xlsx

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PLANNING COMMISSION MINISTRY OF PLANNING DEVELOPMENT & SPECIAL INITIATIVES *-*-*-*-* List of Candidates for the Post of Assistant (BS-15) COMSATS UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD Sr. No. Roll No Name Father's Name 1970 AI - 01 Aamir Khan Malik Abdul Maalik 743 AI - 02 Aamir Khurshid Khurshid Ahmad 283 AI - 03 Aamna Bashir Muhammad Bashir 2534 AI - 04 Aaqib Naeem Muhammad Naeem 281 AI - 05 Aashar Hussain Tassadaq Hussain 2532 AI - 06 Abbas Ahmad Muhammad Yousaf 7318 AI - 07 ABDUL BASIT MUHAMMAD YOUSAF 3449 AI - 08 ABDUL BASIT KHAN Rais Ahmad Khan 6909 AI - 09 ABDUL BASIT QURESHI Gulzar Ahmed Qureshi 4940 AI - 10 ABDUL FATTAH Amanullah 2564 AI - 11 Abdul Haq Abdul Rasheed 3960 AI - 12 ABDUL HASEEB Rahman Ud Din 8091 AI - 13 ABDUL HASEEB RANA Abdul Jabbar 7862 AI - 14 ABDUL JABBAR Haji Jan Muhammad 1595 AI - 15 Abdul Jabbar Qayyum Abdul Qayyum Abbasi 2202 AI - 16 Abdul Khaliq Hazoor Bux 6666 AI - 17 ABDUL MANAN Muhammad Aslam 3376 AI - 18 ABDUL MATEEN Abdul Rauf 3798 AI - 19 ABDUL MUQEET Ashiq Hussain Bhatti 930 AI - 20 Abdul Qudoos Raza Muhammad 5814 AI - 21 ABDUL RAHMAN Abdul Fatah 2993 AI - 22 ABDUL RAZZAQ Qurban Ali 499 AI - 23 Abdul Rehman Ejaz Ahmad 3203 AI - 24 ABDUL ROUF GHULAM RASOOL 5166 AI - 25 ABDUL SAEED BHUTTO Abdul Jabbar Bhutto 3786 AI - 26 ABDUL SAMAD Abdul Rashid 5699 AI - 27 ABDUL SAMAD RIAZ AHMED KHAN 2525 AI - 28 Abdul Samad Khan Abdul Rahim Khan 2197 AI - 29 Abdul Shakoor Shah Muhammad 2476 AI - 30 Abdul Shakoor Sohor Ghulam Murtaza 186 AI - 31 Abdul Subhan Khan Muhammad Arif Khan 2446 AI - 32 Abdul Wahab -

List of Mbbs Graduates for the Year 1997

KING EDWARD MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, LAHORE LIST OF MBBS GRADATES 1865 – 1996 1865 1873 65. Jallal Oddeen 1. John Andrews 31. Thakur Das 2. Brij Lal Ghose 32. Ghulam Nabi 1878 3. Cheytun Shah 33. Nihal Singh 66. Jagandro Nath Mukerji 4. Radha Kishan 34. Ganga Singh 67. Bishan Das 5. Muhammad Ali 35. Ammel Shah 68. Hira Lal 6. Muhammad Hussain 36. Brij Lal 69. Bhagat Ram 7. Sahib Ditta 37. Dari Mal 70. Atar Chand 8. Bhowani Das 38. Fazi Qodeen 71. Nathu Mal 9. Jaswant Roy 39. Sobha Ram 72. Kishan Chandra 10. Haran Chander Banerji 73. Duni Chand Raj 1874 74. Ata Muhammad 1868 40. Sobhan Ali 75. Charan Singh 76. Manohar Parshad 11. Fateh Singh 41. Jowahir Singh 12. Natha Mal 42. Lachman Das 1879 13. Ram Rich Pall 43. Dooni Chand 14. Bhagwan Das 44. Kali Nath Roy 77. Sada Nand 15. Mul Chand 45. Booray Khan 78. Mohandro Nath Ohdidar 16. Mehtab singh 46. Jodh Singh 79. Jai Singh 47. Munna Lal 80. Khazan Chand 48. Mehr Chand 81. Dowlat Ram 1869 49. Jowala Sahai 82. Jai Krishan Das 17. Taboo Singh 50. Gangi Ram 83. Perama Nand 18. Utum Singh 52. Devi Datta 84. Ralia Singh 19. Chany Mal 85. Jagan Nath 20. Esur Das 1875 86. Manohar Lal 21. Chunnoo Lal 53. Ram Kishan 87. Jawala Prasad 54. Kashi Ram 1870 55. Alla Ditta 1880 22. Gokal Chand 56. Bhagat Ram 88. Rasray Bhatacharji 57. Gobind Ram 89. Hira Lal Chatterji 90. Iktadar-ud-Din 1871 1876 91. Nanak Chand 23. Urjan Das 58. -

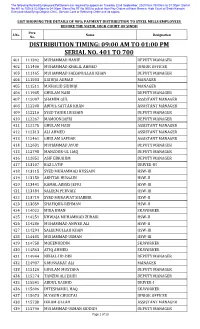

Distribution Timing: 09:00 Am to 01:00 Pm Serial No

LIST SHOWING THE DETAILS OF 90% PAYMENT DISTRIBUTION TO STEEL MILLS EMPLOYEES BEFORE THE NAZIR, HIGH COURT OF SINDH Pers. S.No. Name Designation No. DISTRIBUTION TIMING: 09:00 AM TO 01:00 PM SERIAL NO. 401 TO 700 401 111392 MUHAMMAD HANIF DEPUTY MANAGER 402 111406 MUHAMMAD KHALIL AHMED JUNIOR OFFICER 403 111465 MUHAMMAD FAIZANULLAH KHAN DEPUTY MANAGER 404 111503 S.SHUJA AHMAD MANAGER 405 111511 M.KHALID SIDDIQI MANAGER 406 111945 GHULAM NABI DEPUTY MANAGER 407 112097 SHAMIM GUL ASSISTANT MANAGER 408 112208 ABDUL SATTAR KHAN ASSISTANT MANAGER 409 112216 SYED TAHIR HUSSAIN DEPUTY MANAGER 410 112267 MAMOON JAFRI DEPUTY MANAGER 411 112275 GHULAM HADI ASSISTANT MANAGER 412 112313 ALI AHMED ASSISTANT MANAGER 413 112461 GHULAM SAFDAR ASSISTANT MANAGER 414 112631 MUHAMMAD AYUB DEPUTY MANAGER 415 112798 MANZOOR-UL HAQ DEPUTY MANAGER 416 112852 ASIF EBRAHIM DEPUTY MANAGER 417 113107 BAZ LATIF DRIVER-III 418 113115 SYED MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN HSW-III 419 113158 AKHTAR HUSSAIN HSW-II 420 113441 KAMAL ABBAS JEFRI HSW-III 421 113484 SALEEM PERVAIZ HSW-III 422 113719 SYED MURAWAT SHABBIR HSW-II 423 113859 SHAFIQUR-REHMAN HSW-II 424 114022 MIRA KHAN SK.WORKER 425 114251 KHWAJA MUHAMMAD ZUBAIR HSW-II 426 114286 MUHAMMAD ANWER ALI HSW-II 427 114294 SALEEMULLAH KHAN HSW-III 428 114405 MUHAMMAD USMAN HSW-III 429 114758 MOEENUDDIN SK.WORKER 430 114863 ATIQ AHMED SK.WORKER 431 114944 NEHAL-UD-DIN DEPUTY MANAGER 432 114987 S.MUSSARAT ALI MANAGER 433 115126 GHULAM MUSTAFA DEPUTY MANAGER 434 115274 TANZIM ALI ZAIDI DEPUTY MANAGER 435 115541 ABDUL RASHID DRIVER-I 436 115606 IHTESHAMUL HAQ SK.WORKER 437 115673 M.YASIN CHUGTAI JUNIOR OFFICER 438 115738 IKRAM-ULLAH ASSISTANT MANAGER 439 115746 MUHAMMAD USMAN SIDDIDI DEPUTY MANAGER Page 1 of 13 LIST SHOWING THE DETAILS OF 90% PAYMENT DISTRIBUTION TO STEEL MILLS EMPLOYEES BEFORE THE NAZIR, HIGH COURT OF SINDH Pers. -

Scanned by Camscanner

Scanned by CamScanner Pre-Matric Pending Application (Fresh) DOMICILE STATE/ Contact DOMICILE Institute Name/ NAME OF THE FATHER'S NAME / Person/Registered Contact Person Sr. # DISTRICT Aishe/Dise Code APPLICATION ID STUDENT MOTHER'S NAME Status Email ID Mobile No Phone No Salwan Public School, DELHI / Rajinder Nagar New MOHD SHAMINUDDIN / Pending at Institute 1 CENTRAL Delhi/07060314902 DL201920006889626 MD ANAS PRAVEEN KHATUN Level [email protected] 9810847771 / 0 0 Govt. Sarvodaya Vidyalaya (Dr.Rajendra Prasad), DELHI / President Estate, New Pending at Institute DRRAJENDRAPRASAD.KV@GMAI 9868950203 / 2 CENTRAL Delhi/070501ND404 DL201920007788029 FATIMA QURESHI MOHD RAIS / RUBINA IIYAS Level L.COM 9411394530 0 DELHI / DAYANAND ROAD- Pending at Institute 9717522303 / 3 CENTRAL SKV/07060115303 DL201920002363364 WALIYA HASAN MOHD AZAM / SABANA Level [email protected] 9211803279 9211803279 DELHI / DAYANAND ROAD- MOHD ISHAAQ KHAN / Pending at Institute 9717522303 / 4 CENTRAL SKV/07060115303 DL201920002525942 HAMID KHAN MURSHIDA Level [email protected] 9211803279 9211803279 Francis Girls Sr. Sec. School, DELHI / 17, Darya Ganj, New Pending at Institute 5 CENTRAL Delhi/07060215308 DL201920008647073 MARIYAM LAEEQ AHMAD / RUHINA Level [email protected] 9810692727 / 0 0 ZPPS DELHI / DANGEWASTI/2730060020 Pending at Institute 6 CENTRAL 5 DL201920008847503 MAJHARUL ISLAM KAMAL / ANSARA Level [email protected] 9823217288 / 0 0 QURESH NAGAR(URDU DELHI / MEDIUM)- Pending at Institute 7 CENTRAL GGSS/07020108802 DL201920005222143 RAQEEBA JAHAN MD TUFAIL / ISHRAT JAHAN Level [email protected] 9910600332 / 0 0 DELHI / UJAWAL JR. JAMIRUL ISLAM / TAHAMINA Pending at Institute 8 CENTRAL COLLEGE/27280800107 DL201920001899011 RAHIMA KHATUN KHATUYN Level [email protected] 8670499551 / 0 0 DELHI / KAROL BAGH, LINK MD MAHMOOD ALAM / Pending at Institute 9810877320 / 9 CENTRAL ROAD,RPVV/07060109101 DL201920006835248 MOHD MASOOM ROSHAN KHATOON Level [email protected] 9810877320 1123622367 Francis Girls Sr. -

No Peace If Kashmir Is Un-Resolved

Soon From LAHORE & KARACHI A sister publication of CENTRELINE & DNA News Agency www.islamabadpost.com.pk ISLAMABAD EDITION IslamabadFriday, March 26, 2021 Pakistan’s First AndP Only DiplomaticO Daily STPrice Rs. 20 No peace if Pakistan deeply Taylor Swift ends Kashmir is values it’s ties legal battle with un-resolved with Hungary US theme park Detailed News On Page-01 Detailed News On Page-08 Detailed News On Page-06 Pakistan, Briefs PAKISTAN DAY PARADE GLIMPSES Egypt vow to Kanwal cooperate Naseem dies DNA ISLAMABAD: The 9th round staff RepoRt of Pakistan-Egypt Annual Bi- lateral Consultations (ABC) ISLAMABAD: Veteran news was held at the Egyptian Min- personali- istry of Foreign Affairs in. Dr. ty Kanwal Khalid Hussain Memon, Spe- Naseem cial Secretary (Middle East), brethed Ministry of Foreign Affairs her last on of Pakistan and Ambassador Thursday. Tarek El-Wassimy, Assistant Kanwal Naseer had been Foreign Minister for Asian associated with PTV and Ra- Affairs of Egyptian Foreign dio Pakistan for more than Ministry led their respec- 5 decades. Kanwal Naseer tive delegations. made his first investment on Both sides reviewed the November 26, 1964 when entire gamut of bilateral PTV was established. She relations and agreed to started her career at the age work together on a num- of 17 Kanwal Naseer also ber of proposals in the ar- played the first lead role in eas of education, culture, the TV drama. For the first housing, transportation, time on the TV screen, Kan- communication and remote wal Naseem was the one to sensing, and cooperation narrate “My name is Kanw- between Gwadar and Suez al Naseer and today, televi- Ports authorities. -

Wireless Earphone 2019

LIST OF WIRELESS EARPHONE WINNERS FIRST POSITION IN INSTITUTION S. NO. ROLL NO. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME CLASS INSTITUTION CITY/DISTRICT IQRA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL 1 19-021-11866-1-021-S AAILA HAMMAD HAMMAD ANWAR 1 KARACHI SYSTEM AIRPORT CAMPUS MUHAMMAD JUNAID THE CITY SCHOOL GULSHAN 2 19-021-11459-1-001-S AAILA JUNAID 1 KARACHI ZAFAR CAMPUS B MAJID HAIDER KHAN LAHORE GRAMMAR SCHOOL 3 19-42-11890-1-001-S AANIYAH KHAN NIAZI 1 LAHORE NIAZI DEFENCE CAMPUS THE MILLENNIUM EDUCATION 4 19-051-11547-1-001-S ABDUL AAHAD TAHIR SALEEM 1 ISLAMABAD GREENWICH CAMPUS 5 19-56-11640-1-002-S ABDUL AHAD ABDUL QUDDUS JAVAID 1 LAHORE GRAMMAR SCHOOL SHEIKHUPURA ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL NORTH 6 19-021-11028-1-008-S ABDUL AHAD KHAN NADEEM KHAN 1 KARACHI CAMPUS THE OVERSEAS GRAMMAR 7 19-42-11765-1-002-S ABDUL ALEEM ALI RAZA 1 LAHORE SCHOOL JUNIOR SECTION HAMDARD PUBLIC SCHOOL 8 19-021-11589-1-010-S ABDUL BAARI MOEED FAROOQI 1 KARACHI JUNIOR SECTION ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL & 9 19-51-11793-1-001-S ABDUL HADI WAQAS AHMED 1 RAWALPINDI COLLEGE JARRAR GARRISON 10 19-51-11083-1-061-S ABDUL HADI FAYYAZ FAYYAZ AHMED 1 SAINT MARY'S ACADEMY RAWALPINDI PASBAN ARMY PUBLIC DERA ISMAIL 11 19-0966-11438-1-004-S ABDUL HADI HADI MUHAMMAD ADIL ZEB 1 SCHOOL KHAN ROOTS MILLENNIUM SCHOOL 12 19-55-11541-1-007-S ABDUL HADI SHAHID NASEEM SHAHID 1 GUJRANWALA HOLBORN CAMPUS MUHAMMAD FAHEEM THE CITY SCHOOL LIAQUAT 13 19-022-11712-1-007-S ABDUL HASEEB KHAN 1 HYDERABAD KHAN CAMPUS 14 19-51-11315-1-002-S ABDUL MOHEED IMRAN SHEHZAD 1 ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL (SCO) RAWALPINDI AZEEMI PUBLIC HIGHER 15 19-021-11412-1-010-S