Rethinking Informality in the Study of West African Labour Migrations Rossi, Benedetta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niger ------Projet D’Approvisionnement En Eau Potable Et D’Assainissement En Mileu Rural Dans Les Regions De Maradi, Tahoua Et Tilllaberi

Avis d'Appel d'Offres International (AAOI) REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ------------------- PROJET D’APPROVISIONNEMENT EN EAU POTABLE ET D’ASSAINISSEMENT EN MILEU RURAL DANS LES REGIONS DE MARADI, TAHOUA ET TILLLABERI -------------- Travaux de construction de dix-neuf (19) installations de déferrisation d’eau dans la région de Tahoua. ----------- Appel d'Offres N° : AAOI N° N du Don FAD : 2100155009266 N° du Don RWSSI : 5800155000051 N° du Projet : P-NE-EAO-007 Titre du projet : Projet d’approvisionnement en eau potable et d’assainissement en milieu rural dans les régions de Maradi, Tahoua et Tillabéry 1. Le Gouvernement de la République du Niger a obtenu un don du Fonds Africain de Développement (FAD) et un don du Fonds fiduciaire de l’Initiative d’Alimentation en Eau Potable et Assainissement en milieu rural (RWSSI) pour financer le coût du Projet d’approvisionnement en eau potable et d’assainissement en mileu rural dans les régions de Maradi, Tahoua et Tilllaberi. Il est prévu qu'une partie des sommes accordées au titre de ce don sera utilisée pour effectuer les paiements prévus au titre du marché. 2. Le Ministère de l’Hydraulique et de l’Environnement invite, par le présent Appel d'Offres, les soumissionnaires intéressés à présenter leurs offres sous pli fermé, pour la réalisation des travaux ci-dessus mentionnés. ALLOTISSEMENT : Les travaux sont subdivisés en deux (2) lots distincts ainsi qu’il suit : Lot 1 : Dix (10) installations dans les départements de Tahoua, Keita et Bouza, dans les vllage de : Barmou, Toro, Rididi, Insafari, Loudou, Gadamata, Hiro, Garhanga, Allakeye, Tama. Lot 2 : Neuf (9) installations dans les départements de Birni NKonni, Illéla et Madaoua, dans les vllage de : Ambaroura, Binguiré, Kahé Damé, Kaoura Alassane, Tsernaoua, Dangona, Tajaé Nomade, Zouraré Sabara et Magaria Makera. -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

Electrical Sector and Renewable Energies SOFTWARE & IT

SOFTWARE & IT SOLUTIONS Electrical Sector and Renewable Energies Copyright © 2008-2019 IED S.A.S, All Rights Reserved. WHO ARE WE? As an independent consulting and engineering firm, IED has been involved in the provision of sustai- nable and strategic energy services since its creation in 1988 . From power systems planning to feasibil- ity studies and operational management, IED offers a wide range of IT solutions to support your needs in the field of electrification, network planning and renewable energy project development. Specialized tools for institutions, companies, local authorities and consulting firms involved in the energy sector. GIS AT THE SERVICE OF PLANNING ACCESS TO ENERGY Geographic information systems (GIS) have the capacity to store and use alphanumeric data as well as geographic data offering new opportunities for the decentralized rural planning sector, energy production and demand assess- ment. IED combines its knowledge of the energy sector with its solid expertise in the design of information systems, the development of alphanumeric and cartographic databases and spatial analysis through several GIS software (ArcGis, Manifold, QGIS...). The data collection (alphanumeric and cartographic) and its consolidation (geographic, topographical, demographic, socio-economic data, etc.) is one of the main capabilities and qualities of IED experts who are used to operating in contexts where data access is often difficult. Overlay of multisectoral data Visualization of different layers of data to take into account a large number of factors influencing the final deci- sion: socio-economic infrastructure, road networks, rivers, protected areas, ...) Publication of decision support maps Production of detailed decision-making maps for decision-makers (wind farm identification, energy constraints, social and environmental impact ...) Dissemination, communication and consensus of data Communication on geographical data, in electronic, paper or on the Internet. -

Aperçu Des Besoins Humanitaires Niger

CYCLE DE APERÇU DES BESOINS PROGRAMME HUMANITAIRE 2021 HUMANITAIRES PUBLIÉ EN JANVIER 2021 NIGER 01 APERÇU DES BESOINS HUMANITAIRES 2021 À propos Pour les plus récentes mises à jour Ce document est consolidé par OCHA pour le compte de l’Équipe humanitaire pays et des partenaires. Il présente une compréhension commune de la crise, notamment les besoins OCHA coordonne l’action humanitaire pour humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de garantir que les personnes affectées par une personnes ayant besoin d’assistance. Il constitue une base crise reçoivent l’assistance et la protection dont elles ont besoin. OCHA s’efforce factuelle aidant à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de surmonter les obstacles empêchant de la réponse. l’assistance humanitaire de joindre les personnes affectées par des crises et PHOTO DE COUVERTURE est chef de file dans la mobilisation de l’assistance et de ressources pour le compte MAINÉ SOROA/DIFFA, NIGER du système humanitaire. Ménage PDIs du village Kublé www.unocha.org/niger Photo: IRC/Niger, Novembre 2020 twitter.com/OCHA_Niger?lang=fr Les désignations employées et la présentation des éléments dans le présent rapport ne signifient pas l’expression de quelque opinion que ce soit de la part du Secrétariat des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique d’un pays, d’un territoire, d’une ville ou d’une zone ou de leurs autorités ou concernant la délimitation de ses frontières ou de ses limites. La réponse humanitaire est destinée à être le site Web central des outils et des services de Gestion de l’information permettant l’échange d’informations entre les clusters et les membres de l’IASC intervenant dans une crise. -

Rapport De Mission Corrige

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ………………… MINISTERE DES MINES ET DE L’ENERGIE Improving Economic and Social Impact of Rural Electrification (IMPROVES-RE) Amélioration de l’impact social et économique de l’électrification rurale BURKINA FASO, CAMEROUN, MALI et NIGER RAPPORT DE MISSION Du 11 Mars 2006 au 05 Avril 2006 ENQUETES SOCIOECONOMIQUES APPROFONDIES DANS LA ZONE PILOTE DEPARTEMENTS DE KEITA ET ABALAK Coordination européenne Innovation Energie Développement (IED) 2, chemin de la chauderaie 69340 Francheville – France Tél. +33 4 72 59 13 20, Fax : +33 4 72 59 13 39 [email protected] www.ied-sa.fr Coordination européenne ANNEXES SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. ORGANISATION DE LA MISSION.............................................................................................................................. 2 2.1. CHOIX DES LOCALITES......................................................................................................................................................2 2.2. FICHES D’ENQUETES.........................................................................................................................................................2 2.3. PREPARATION DE L’EQUIPE.............................................................................................................................................2 III. DEROULEMENT DE LA MISSION........................................................................................................................... -

Rethinking Informality in the Study of West African Labour Migrations Rossi, Benedetta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Tubali's trip : rethinking informality in the study of West African labour migrations Rossi, Benedetta DOI: 10.1080/00083968.2014.918323 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Rossi, B 2014, 'Tubali's trip : rethinking informality in the study of West African labour migrations', Canadian Journal of African Studies, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 77-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2014.918323 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Eligibility for repository : checked 2/12/2014 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Hadiza Hassane (F, 80 Years), Djiouta NI

NIGER Four interviewing sites were selectedin Niger, with the assistanceof Dr K. Mariko.Ibrahim Mamane and ZeinabouBa, studentsat the University of Niamey,interviewed settled farmers in Takieta, near Zinder, on the proposed site of an SOS Sahel agro-forestry project. A second group of students conducted interviews in areas where projects had ended. In Abalak, a sitewhere many pastoralists were settled after the 1984-85 drought, Ibrahim Abdoulaye and Melle Ibrahim Habitsou spoke to pastoralists and agro-pastoralists, and also to communities of small-scaleirrigated farmers and fishermen.These interviews were conducted in Hausa, Peulh and Tamashek. Kollo Mamadou Ousmane interviewed a groupof Hausa-speaking settled farmersin Tibiri. He also carried out work at the fourth site, Boubon, where he interviewed local fishermen participating in a fish-farming project, as well as sedentary farmers. Interviews were conducted in Hausa and in Djerma, and were coordinated by Rhiannon Barker. Hadiza Hassane (F,80 years), Djiouta NI Hadiza told her story sitting in the shadeof a tree, her two 50-year-old sons shouting directly into her deaf ears and trying to take over the narrative themselves when their mother’s memoryneeded jogging. I was born in Garagoumsa village, a few kilometres away. My parents were farmers and hunters. My father decidedto leave and was the first to arrive here and dig a well. Thanks to his efforts, we were able to settle; and many of our relatives from Garagoumsa cameto join us. When we arrived, there was nothing here but huge trees. The forest was so thick that, even in daylight, it was enough to scareyou. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Projet D'amenagement Et De Bitumage De La Route Tamaske-Kalfou-Kolloma

Langage : French Original: French PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE BITUMAGE DE LA ROUTE TAMASKE-KALFOU-KOLLOMA Y COMPRIS LA BRETELLE DE TAMASKE-MARARRABA (63 KM) PAYS: REPUBLIQUE DU NGER RESUME DU PLAN ABREGE DE REINSTALLATION (PAR) Date: Mai 2019 Chef de Projet: M. SANGARE Ingénieur des Transports, Consultant RDGW3 - J.J. NYIRUBUTAMA Economiste des transports en Chef, RDGS4; L’Equipe du projet - E. C. KEMAYOU Spécialiste en Fragilité RDGWO ; - N. NANGMADJI Expert en sauvegarde environnementale et sociale - Consultant, SNSC/RDGW4 ; - T. OUEDRAGO Expert en Genre, Consultant RDGWO ; - R. SARR SAMB Spécialiste en Acquisitions, SNFI.l Chef de Division Régional : Jean Noel ILBOUDO Directeur Sectoriel: Amadou OUMAROU Directeur Général Adjoint : SERGE NGUESSAN Directeur General: Marie-Laure AKIN-OLUGBADE I. INTRODUCTION Le présent document résume le Plan d’Action de Réinstallation du projet d’aménagement et de bitumage de la route Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské-Mararraba (63 km) dans la région de Tahoua. Ce projet s’inscrit dans le cadre du Programme de la Renaissance acte 2 du gouvernement de la République du Niger, à travers lequel un Plan de Développement Économique et Social (PDES) 2017-2021 a été élaboré et adopté le gouvernement. Ce PDES prend en compte les projets et programmes prévus par la Stratégie Nationale des Transports en vue de renforcer et préserver le réseau routier national, un appareil économique pour un développement durable. Ainsi, le secteur des transports a été identifié comme un secteur prioritaire parmi les secteurs contribuant à la création de richesse et d’emploi. A cet effet, le gouvernement de la 7ème République a sollicité l’appui de la Banque Africaine de Développement afin de réaliser l’aménagement et le bitumage du tronçon Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské – Mararraba dans la région de Tahoua. -

La Petite Ville, Un Milieu Adapté Aux Paradoxes De L

La petite ville, un milieu adapté aux paradoxes de l’Afrique de l’Ouest : étude sur le semis, et comparaison du système spatial et social de sept localités : Badou et Anié (Togo) ; Jasikan et Kadjebi (Ghana) ; Torodi, Tamaské et Keïta (Niger) Frédéric Giraut To cite this version: Frédéric Giraut. La petite ville, un milieu adapté aux paradoxes de l’Afrique de l’Ouest : étude sur le semis, et comparaison du système spatial et social de sept localités : Badou et Anié (Togo) ; Jasikan et Kadjebi (Ghana) ; Torodi, Tamaské et Keïta (Niger). Géographie. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne - Paris I, 1994. Français. tel-00111236v2 HAL Id: tel-00111236 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00111236v2 Submitted on 27 Nov 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. La petite ville, un milieu adapté aux paradoxes de l'Afrique de l'Ouest : étude sur le semis, et comparaison du système spatial et social de sept localités (Togo, Ghana, Niger) / Frédéric Giraut/ Thèse Université Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1994 Université de PARIS I PANTHEON-SORBONNE THESE de DOCTORAT -

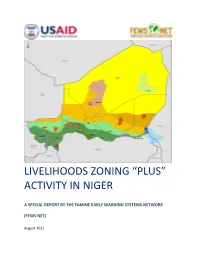

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Fichier À Télécharger

IMPROVES-RE Improving Economic and Social impact of Rural Electrification Co-funded by EUROPEAN COMMISSION COOPENER INTERIM TECHNICAL IMPLEMENTATION REPORT PERIOD: 1st April 2005 – 31st July 2006 Contract N° EIE/04/133/S07.40682 IED ETC Foundation RISOE European coordination Innovation Energie Développement, 2 chemin de la chauderaie 69340 Francheville – France Tel. +33 4 72 59 13 20 – Fax : +33 4 72 5913 39 Email : [email protected] IMPROVES-RE EIE/04/133/S07.40682 - Interiim techniicall iimpllementatiion report CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Global situation 3 1.2 Reminder on Work Packages arrangement and Project Schedule 4 1.3 Content of report 6 2 STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION PER WORK PACKAGE 8 2.1 WP1: Review of planning approaches and institutional framework, and multi- sector data collection 8 WP1.1: Review of context (D2) 8 WP1.2: Cross sectorial partnerships 8 WP 1.3: Multi-sector data GIS (D3) 9 2.2 WP2: Integrating cross sectorial and geographic aspects in Rural Electrification Plans 9 WP2.1: Methodology of integrated cross-sectorial rural electrification planning 9 WP2.2: Integrating cross sectorial dimension in Rural Electrification Plans (D5) 16 2.3 WP3: Development of local Rural Electrification and multi-sectorial plans 21 WP3.1: The GIS Master planning tool GEOSIM© 21 WP3.2: Selection of pilot area 21 WP3.3: Elaboration of local Rural Electrification and multi-sector plans 23 2.4 WP 4: Local stakeholders mobilization 24 First results of the planning 24 WP4.1 and 4.2: Identification of local stakeholders and discussion of different